about the writer

Daniel Raven-Ellison

Daniel is a guerrilla geographer, National Geographic Explorer and led the successful campaign to establish London as the world’s first National Park City.

about the writer

Alison Barnes

Alison has spent over 20 years of her professional life in roles linking the natural environment with people, currently as the Chief Officer at New Forest National Park Authority. Alison is an elected Fellow of the Landscape Institute and the RSA and is a Trustee of the National Park City Foundation.

Introduction

Cities are constellations of green, blue, and grey spaces. Some cities have more green and blue space than others, but in just about every city such spaces are an idiosyncratic mix of some big parks, small parks, neighborhood spaces, open spaces both formal and informal, community gardens, private gardens, ivy covered walls, flowerpots, and window boxes.

Cities are also our habitat, places where 70% of the world’s population will live by 2050 and where green, blue and grey spaces are home to a surprising diversity of life. They lie at the frontier of the crucial relationships between people and nature that will enable responses to climate emergency and nature loss.

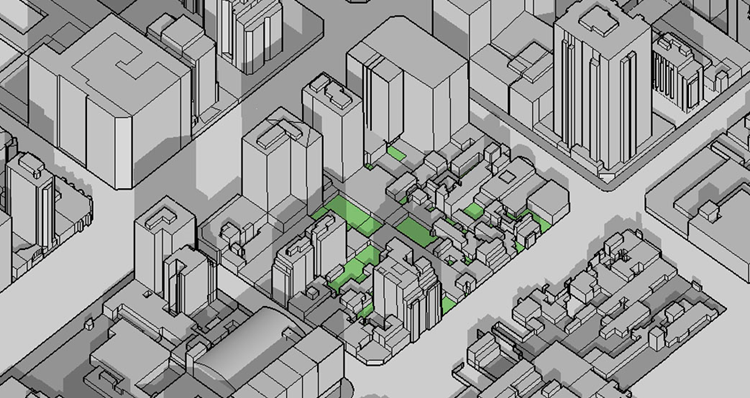

Often we think of spaces in cities as individual, administered differently, distinct. But just like aggregations of street trees, private trees, and park trees can add up to an “urban forest”, so too can the broad constellation of urban green, blue, and open spaces “add up” to something bigger: a city-scale park.

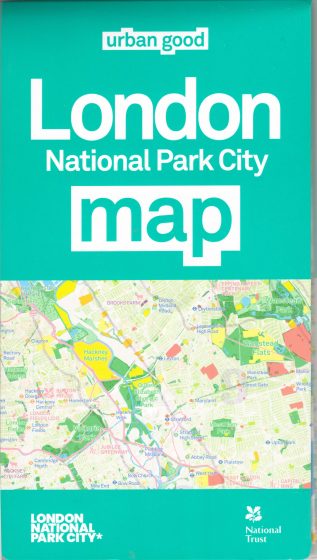

The London National Park City idea is both a formal recognition of the scope and benefits of the macro-park that is all London’s open spaces, and also a call for London’s population to see and get engaged with their myriad green spaces.

The six year campaign saw London National Park City launched in 2019. Other cities will follow. The idea is both a formal recognition of the scope and benefits of the macro-park that is all London’s open spaces, and also a call for London’s population to see and get engaged with their myriad green spaces. It is a place, a vision, and a city-wide community that is acting together to make life better for people, wildlife and nature. A defining feature is the widespread commitment to act so people, culture, and nature work together to provide a better foundation for life. Because it’s about the city’s entire landscape, everybody can be involved every day and it has the potential to exist forever.

Can this idea be applied in other cities? How? We asked a variety of people involved in parks and open space around the world. Some are in cities actively contemplating such a national park city approach. For others, it was a new idea. We asked: What if your city were a National Park City, analogous to what London created? What it would be like? What would it take to accomplish?

We are interested in your thoughts on this question also, so please take moment to answer some short questions, below.

Special thanks to several people who helped put this roundtable together: Neil McCarthy (World Urban Parks), Ingrid Coetzee (ICLEI Africa), Dominic Regester (Salzburg Global Seminar). This roundtable is an outgrowth of the TNOC Summit Session “Spreading the London National Park City idea”.

about the writer

Eduardo Guerrero

Eduardo Guerrero is a biologist with over 20 years of experience in projects and initiatives involving environmental and sustainable development issues in Colombia and other South American countries.

Eduardo Guerrero

Cities in nature and nature in cities

National Park City—similar in spirit to the Colombian initiative Biodivercities— are necessary evolutions of traditional paradigms in urban and peri-urban planning. In cities, nature conservation and citizens wellbeing are part of the same equation, not contradictory goals.

When you arrive by plane into a city, what you see from the air is a city inserted in a regional landscape. The ecosystem matrix of Colombian cities is quite diverse. Some urban centers have been built inside Andean or Caribbean ecosystems, other Amazonian, or within the Orinoquia region or in the middle of the Pacific tropical rain forest.

A city is not an isolated landscape from its regional surrounding territory. On the contrary, cities are immersed into biomes. From a broad landscape perspective, they are patches of transformed soil in the middle of natural ecosystems. So, the question is: should we plan cities as part of nature or aside nature?

Under this perspective, what’s the role of urban protected areas? What’s the role of designed green spaces and green infrastructure? Should urban metropolitan parks, pocket parks, street trees and urban protected areas be part of the same functional ecological network?

In Colombia we have positioned the concept of main ecological structure, that is the natural resources base, as a tool to integrate protected areas and other green spaces to land use planning. With the support of Ministry of Environment and regional and local environment authorities, many cities have identified their main ecological structure trying to link these with regional ecological networks which support socio-economic development.

There is a discussion dealing with the official status of urban protected areas. The National System of Protected Areas does not include them, despite local authorities have declared many. The National Parks agency recognizes them under a secondary figure named “complementary conservation strategy”, related to the Convention on Biological Diversity’s concept of “Other Effective Area–Based Conservation Measures (OECM)”. Debate is opportune and important because it stimulates a reflection about urbanization, nature, and sustainable development. Even if small and transformed, urban protected areas and other green spaces have a key function, not only in terms of ecological connectivity but also in terms of social and economic sustainability.

In the real world, regardless of formal recognition, many of these urban protected areas show remarkable conservation achievements thanks to effective synergies among authorities and citizens.

A Colombian initiative analogous to London’s National Park City campaign

Beyond the name, I share the vision which inspires the National Park City idea: to make cities where people, places and nature are better connected.

In that sense, the example of London is quite motivating. I like such an initiative driven by a collective partnership of citizens, NGOs, and local authorities to convince cities and their residents to be greener, healthier, and wilder.

National Park City initiative challenges the classic concept of National Park. A National Park City is not seeking to be declared as an official National Park under the national protected areas systems. Official or not, what is important is the campaign itself and its effectiveness mobilizing a city around a powerful idea.

Coincidentally, in Colombia, national government is developing an initiative called “Biodivercities”, aiming to integrate biodiversity and the main ecological structure as the foundations for a sustainable urban development.

Under the logic of this initiative, an urban center is aimed at the adopted and adapted concept of “biodivercity” when planning, organizing its territory, and managing its social and economic development in a sustainable and innovative way in harmony with its natural resources base.

A valuable element of the initiative is the synergy between conservation, innovation, and green entrepreneurship. A “biodivercity” not only must conserve biodiversity to preserve ecosystem services. It is also expected to promote bioeconomy, science, technology, and innovation as structural axes of sustainable development and, at the same time, use natural resources efficiently, with a focus on circular economies.

Ideas such as “National Park City” or “Biodivercity” (the Colombian initiative) challenge the conventional and traditional approaches to urban nature. The point is that we need a paradigm evolution in urban and peri-urban planning. In cities, nature conservation and citizens wellbeing are part of the same equation, not contradictory goals.

about the writer

Gillian Dick

Gillian is the Manager of Spatial Planning – Research & Development team, Development Plan Group at Glasgow City Council. She has a BSc (Hons)Town Planning, Heriot-Watt University and BSc (Hons) Human Geography, The Open University. She is a chartered member of the Royal Town Planning Institute and is the past Chair on their Partnership and Accreditation Panel. She is the chair of the Technical University Dublin Partnership Board, and a member of the RTPI Education and lifelong learning committee. She is an Exec member of AGI Scotland and is also a member of the Scottish Landscape alliance Exec.

Gillian Dick

I’d love the Glasgow conurbation to think about being a national park city. But it needs to be a co-production that all interested stakeholders can comfortably sign up to. Not something that is foisted on the city because of a bright shiny campaign.

For London to become the first national park city a movement was created around a campaign to get all 32 boroughs and the London Assembly to sign up to the concept and then to agree a shared charter. For Glasgow to become a National Park City it would only require possibly eight councils to get on board to create a shared vision for a liveable, sustainable and green city. It could be argued that the Council’s in and around Glasgow are already working on a shared vision through their individual Development Plans; Open Space Strategies and colloborative work on the City Region and delivery of the Central Scotland Green Network. As Council officials we are already working collaboratively with partners, whether governmental, community or third sector to provide great places that allow the community to live, work and play.

Whilst welcoming the campaign, there is a real risk that it could distract from the good work that is already ongoing within the City and the surrounding Councils, and bring an added layer of complexity that is difficult to deliver. Conversations with the campaigners have identified that they are developing a vision that they would like campaign supporters and possibly the City Authority to sign up to.

But the campaign doesn’t start from an understanding of what the baseline for open space is for the City or Scotland. There appears to be an assumption that the City doesn’t understand fully what open space can deliver for its communities. The campaign doesn’t appear to acknowledge the difference between legally protected open space and development or vacant and derelict land that has naturally greened. It doesn’t do anything to recognise the limited resources that are available within Cities and the evidence base that is being worked on to try to raise the profile of open space as a key asset for Local Authorities (here and here).

The ideas that fed into the campaign in London are already being worked on in Scotland. The recent Planning bill has made the creation of open space strategies a statutory requirement for all Scottish Councils. The development and use of the Place Standard and the Place Principal are emphasising the health benefits of open space. As a front runner city for the H2020 Connecting Nature project www.connectingnature.eu is developing the ideas of nature-based solutions that deliver great spaces with multiple benefits for society, economy, environment, and health and wellbeing. Early conversations are being held at a national level about updating the typologies for open space; for example, how you measure their quality and whether they are fit for function and how you judge there accessibility for all. Community empowerment is encouraging more citizen science and citizen engagement in our places and spaces.

It’s very easy to campaign today. All you need is a phone and internet access for your voice to be heard. It’s really easy to shout at people and say you should be doing this and look at all the people who also think that you should do this. It’s easy to say there are only a few of us doing this in our spare time, we’re not a big noise.

But it only takes one voice saying something that captures the imagination. In the UK we know this from the political climate we are currently living through. It is far harder to be part of the solution. It would be better to spend energy working collaboratively with the eight Councils that cover the Glasgow area and other supporters to co-produce a vision for what calling Glasgow a national Park city would actually mean in reality. Imposing a vision upon the city employees to implement, without due regard to the political landscape that we are working in, is not collaboration. In fact, it could create conflict and difficulty, and runs the risk of polarising views.

I’d love the Glasgow conurbation to think about being a national park city. But it needs to be a co-production that all interested stakeholders can comfortably sign up to. Not something that is foisted on the city because of a bright shiny campaign. Because at the end of the day, it will not be the campaigners that will implement any designation. It will be the folk that work for the Councils and Scottish Government who will have to make this happen. Please work with us and stop shouting at us.

Disclaimer: the views expressed in this response are those of the author, and not necessarily those of her employer.

about the writer

Ioana Biris

Ioana Biris is a social psychologist and co-owner of Nature Desks, a social enterprise that promotes urban nature, work and wellbeing. Nature Desks redesigns our relation with the urban green through events, content, products and placemaking.

Ioana Biris

In 2025 Amsterdam will celebrate its 750th anniversary. This could be the perfect moment to join the family of National Park Cities and act together with other cities around the world to the common purpose of creating greener, healthier and wilder urban environments.

Another study shows that the amount of green in Amsterdam has decreased constantly over the last years. The capital is growing in terms of population and housing but the number of “green” square meters in the city is not growing at the same pace. Looking at the positive side, the water of Amsterdam (almost 25% of the city’s land use) has never been cleaner, a “green” local government was elected in March 2018 and—for me personally the most relevant fact—the bottom-up civil movement promoting a healthy, sustainable, and green city is continuously growing. People organize themselves and find each other, share information, are proactive, have great ideas. The community is involved.

My city is—just as all other cities in the world—so much more than its streets, buildings, culture, or economic activity. Amsterdam is a unique green and blue urban landscape which we unknowingly share with more than 10,000 species of flora and fauna. There are now more than 873,000 residents. By 2040 this figure will rise to 1,000,000. The dynamic infrastructure of the city is under immense pressure to accommodate this influx. We will have to maintain the right balance between growth and wellbeing, while at the same time respecting the quality of urban nature around us.

Can Amsterdam become a National Park City? Yes, the city has the right ingredients to make this happen: the authorities are currently developing a “green vision” and there is a strong bottom-up civil movement. Can we build a better relationship with the nature? Definitely. Do we want a greener, healthier, and wilder city, that is connected with the surrounding nature? Surely.

You might be familiar with the unique Delta Works construction which was created in the southwest of the Netherlands after the North Sea Flood of 1953 to protect a large area of land from the sea. In 2014, a new Delta Programme was announced. The Dutch government will invest 20 billion euros over the next 30 years to protect the country from flooding, mitigate the impact of extreme weather events, and secure supplies of freshwater. It is now the time for a new Delta Programme: the “Delta Plan for Biodiversity Recovery”. This amazing new plan was presented in December 2018 after scientific research showed that the biodiversity is rapidly declining. “Farmers’ organizations, food supply chain partners, researchers, nature and environmental organizations as well as a bank have joined forces for the first time to reverse biodiversity loss in the Netherlands and embark on the road to recovery”.

And event was organized in Amsterdam in November 2019 where local government, bottom-up initiatives, (nature) organizations, artists, and other stakeholders were asked to make a local contribution to this national Delta Plan for Biodiversity Recovery. A manifesto will be presented soon.

In 2025 Amsterdam will celebrate its 750th anniversary. This could be the perfect moment to join the family of National Park Cities and act together with other cities around the world to the common purpose of creating greener, healthier and wilder urban environments. Do you recall the information I shared about the greenest city in the south of the country? Breda will possibly be the first Dutch city to aim for a National Park City status.

Keep an eye on the Netherlands.

about the writer

Tom Rozendal

Tom is coordinator of city in a park near the municipality of Breda.

Tom Rozendal

Breda likes joining the movement of National Park Cities because it is in line with its ambition to become a city in park.

The city of Breda is inspired by initiative and words of Daniel Raven-Ellison that made London the first National Park City of the world. Breda, a city in the southern part of the Netherlands, has for 2030 set three big ambitions on the themes green, hospitality, and a borderless city. For green this is translated: in 2030 Breda wants to be the first city in Europe that lies in a park. This ambition was chosen together with the inhabitants of the city Breda. Residents and organisations agree that the power of Breda is partly located in the green nature and water that is present in large amounts both in the city and the outer area. From this strong position, the municipality wants to work together with residents and interest groups to further strengthen the green. The emphasis is placed in particular on connecting nature reserves through built-up areas. In addition, Breda will strengthen the green already present in the city of Breda.

Breda is a historic city in which nature occupies an important position. The city originated on the River Mark. Breda is committed to making the river visible again in the city centre. In the final phase, bringing the river back must be combined with nature development. Especially on the outskirts of the city we find nature reserves whose origin goes back to the 12th century. Together with the National Forestry, the municipality of Breda wants to make the green an even more prominent. Based on the figures of Esri-Nederland, 61% of the area of the municipality is green. Breda believes that a green city contributes to solving problems such as heat stress, climate change, and health problems.

Breda also wants to be an attractive city for its residents and businesses in particular. Due to a good location climate, people would like to live in Breda and stay here. Companies are increasingly choosing Breda to settle. Visitors to Breda combine their day of shopping in a historic centre with a day outside in nature. In short Breda profiles itself as a green city where its inhabitants feel at home and who can be proud of their city.

Breda likes joining the movement of National Park Cities because it is in line with its ambition to become a city in park. Breda is also convinced that it can learn from other cities when it comes to involving residents and parties from the further greening of the city. It is also prepared to share the knowledge it has with other cities. For a good future for our children and grandchildren, it is not enough that only Breda will turn green; all cities should be moving in this direction.

Breda has already invested a lot in the further strengthening of green and nature. Especially in the outer area, the city has made great advances. In the coming years, the municipality will work to mobilise other parties that can contribute to our ambition. In the “week of the future”, residents and organisations are challenged to think about with how this ambition can be shaped—ot only by the municipality but also the partners who are already committed. Furthermore, meetings are organized with architects and Breda is one of the organizers of the “Landschapstrienale”.

Together with our other two ambitions—hospitality and a borderless city—Breda becomes a city in a park and a National Park City.

about the writer

Geoff Canham

Geoff is a Principal Parks and Recreation Specialist and Accredited Parks and Recreation Professional (ARPro). Geoff runs GCC, a specialist parks and recreation consultancy.

about the writer

Gareth Moore-Jones

Gareth has been involved in the sector for 30 years and has been CEO of NZ Recreation Association, National Sport & Recreation Manager for NZ YMCA, interim CEO of Outdoors NZ, and as public health planner in the health sector .

Geoff Canham and Gareth Moore-Jones

The National Parks City Movement is a reflection that nature is a basic human right. It also serves as a vehicle to ask what is it that we need from our landscape, what does a city need from nature to sustain itself?

Parks are democracy. Parks are the best expression of democracy, community, and society, and one that transcends politics, issues, and the negative side of our species more than anything else. But why “ring fence” these areas at all or away from where we live, why disassociate our species from the settings where we perform the best?

The National Park City Movement honours parks perhaps more than National Parks themselves. The National Parks City Movement seeks to ensure that people don’t have a detrimental effect to the environment but through individual and collective actions, and positive impact, leave the environment better than when they found it. The National Parks City Movement achieves a range of existing environmental goals: e.g. carbon zero, various environmental initiatives, etc. Indeed, the statutory National Parks could learn a thing or two from National Parks Cities Movement. In National Parks people are removed from the setting or the Parks are curated as a place where nature is at best conserved and attempted to be preserved. In actual National Parks there is an uneasy relationship with human visitors where they are excluded, managed, regulated and often kept at arms’ length with a range of additional policies that probably best suited to where we live as opposed to where we visit.

The National Parks City Movement is a reflection that nature is a basic human right. It also serves as a vehicle to ask what is it that we need from our landscape, what does a city need from nature to sustain itself? It is a platform for leaders to share a vision for a good future. It’s a reminder that people don’t follow ideas, they follow feelings. When ‘feels good’ to people, people will do it again. The appeal and power from National Parks City Movement is that it’s “bottom up”, it’s about sharing the vision for a good future, it’s about optimism and hope.

At the international launch in London July 2019, many speakers reflected that if we are to have a future we need to look to leaders and some of the things we need to be repeating to our communities. We need to find leaders to remind us not to fear nature but look to engage with it through this optimism of hope. To paraphrase Nelson Mandela, we are a people that make better choices when we make those choices reflecting our hopes, not our fears. Another one of the speaking points was that the National Parks City Movement is in effect a collective and enlightened self-interest. The National Park City Movement is another way of engaging with people that lets them relate to their surroundings and if it feels good then people will follow.

In New Zealand we would use a Maori proverb and to date a number of presentations have been given where this has resonated:

“Na to rourou, nā taku rourou ka ora ai te iwi”.

“With your food basket and my food basket the people will thrive”.

Aotearoa/New Zealand is a country that people have settled in over the past 700 or so years, either escaping over-population of smaller lands, or to simply find more resources. I can report from the other end of the globe from London that this is it; there is nowhere left to go next. We have to make the best of what we have and as it is, most of us live in cities anyway. Even in New Zealand, compared to the rest of the world, where around 83% of the world’s population live in cities, here 87% of us living in urbanised cities. This is good news for the land where the food needs to come from but highlights that National Park Cities is the future. We are the only species that wants to better ourselves, the only species that tells stories, the only species that can turn imagination into something-it’s time we got a better story.

If you’ve seen some of the bigger trilogies recently, you’ll know New Zealanders love a quest. Our quest with Bay of Plenty National Park Region is to take a group of small cities close to each other and the small towns nearby, in an already beautiful area known as the Bay of Plenty bordered by National Parks, and to create the first National Park Region.

Méliné Baronian

The place of nature must not be limited. Let us change and adapt public services based on nature’s skills and know-how.

A national park city must allow:

- To enhance the diversity of its blue and green spaces, in size and type (large parks, small gardens, neighbourhood space, ).

- To optimize available spaces and brownfield Each city currently has its own urban planning constraints. But they all deal with the same environmental issues. Acting in a standardised way is not the solution, only appropriate actions can be effective.

- To enhance these green and blue spaces at the centre of urban policies in order to preserve all the benefits they can bring to reduce the impact of grey nuisances (noise, pollution, difficult access, etc.) that could reduce the benefits of these places.

To achieve this, it is necessary to build on existing initiatives, connect stakeholders, facilitate their implementation, and disseminate results.

We often think that we have to reinvent ourselves to move forward when there are already many materials available before our eyes. The awareness and awakening of citizens is very important. They are the ones who appropriate, discover, and enjoy these places. They are in the best position to provide an informed opinion on the necessary improvements and, above all, to contribute to the success of the project.

Full stakeholder engagement is crucial. No approach, no project can succeed when we do not have the same objective. The methods can sometimes diverge, but it is dialogue and co-creation in respect of others that will make it possible to find the best compromises.

Also realize that each action, regardless of its individual scope, has a significant impact. It resonates beyond its expectations and contributes to creating more livable cities.

In an increasingly complex and regulated society, we are trying to frame a phenomenon that does not need us to accomplish itself: to let nature expand again. It is time to remove all the administrative and regulatory obstacles that sometimes penalise relevant and favourable actions. Common sense and simplicity must be restored to enable these many initiatives to be carried out.

To contribute to the creation of a national park city, the place of nature must not be limited. Let us change and adapt public services based on nature’s skills and know-how. Public lighting, roads, public buildings, stormwater management, waste treatment would become the driving force for improving the well-being and health of the inhabitants.

The city of tomorrow may be greener, more liveable and, finally, less dense because its natural spaces will no longer be only recreational spaces. They will also be spaces capable of guaranteeing the public services of tomorrow. By building cities inspired by nature, connectivity and human-nature interactions would only be enhanced. This will help us to become aware of the services and benefits that nature brings us, and also to better preserve it.

about the writer

Sue Hilder

Sue is an outdoor access specialist, currently at Glasgow City Council, with a background in conservation volunteering and environmental sculpture. She is passionate about greenspace and ecology, and believes both in the intrinsic value of species and habitats for their own sake and in their importance for the physical, spiritual and mental health and wellbeing benefits they offer to the people and communities that live alongside them.

Sue Hilder

In Glasgow, we need to create a grassroots groundswell of support across a broad demographic by sharing our passion; by being generous with our time and knowledge; by amplifying and celebrating the work of our partners; and by being inclusive and open to new ideas and alternative pathways.

What would it be like?

If Glasgow were a National Park City, there would be an extensive network of engaged, empowered and passionate individuals and organisations working together to achieve a future Glasgow:

- where nature is thriving and spaces and places are connected;

- where everyone has the opportunity to be engaged with nature and the outdoors;

- where every child has the chance to learn and have fun in nature every day;

- where the air is clean and healthy;

- where communities are enthused, confident and have the skills to make their neighbourhoods greener, more resilient more environmentally just;

- where people are proud of their natural and cultural heritage;

- where everyone has access to green, healthy, sustainable travel;

- where health and wellbeing statistics are a matter for celebration, rather than despondency;

- where excellent design delivers buildings and spaces that respond to the needs of people and nature;

- where everyone feels empowered to create, and entitled to expect, a greener, healthier and wilder city.

What would it take to accomplish?

We (Glasgow National Park City Group) know that there’s no magic wand and no undiscovered funding pot. A Glasgow National Park City will only be achieved by developing trust, and sharing knowledge, skills, and ideas, amongst people and organisations who are already committed to, or at least interested in, delivering greener, healthier, more resilient, and more biodiversity rich neighbourhoods. We need to create a grassroots groundswell of support across a broad demographic by sharing our passion; by being generous with our time and knowledge; by amplifying and celebrating the work of our partners; and by being inclusive and open to new ideas and alternative pathways. There is no value in a top-down approach; this has to be achieved by “infection”.

Our small group of volunteers needs to grow into a bigger team, and we are inviting people to join us through our website and social media channels, by running and speaking at events, and by word of mouth. We’re realistic about the time it will take to promote the idea and get people on board, and at the same time we will do what we can to take advantage of amazing opportunities like the COP26 climate summit coming to Glasgow in 2020.

about the writer

Snorri Sigurdsson

Dr. Snorri Sigurdsson is a biologist, who has worked for the Department of Environment and Planning in the City of Reykjavík, Iceland for the last six years.

Snorri Sigurdsson

Reykjavík is well suited to be a National Park City—it has all the elements and already many projects that could fit in to this kind of premise. But Icelanders are deeply independent, and any NPC effort will only succeed from the ground up.

It‘s a no-brainer to imagine this idea being applied in other cities. The City of Reykjavík, where I live and work, is truly rich in nature, with pristine habitats of great diversity and value. It is a coastal city, surrounded by the vast blue stretches of the North Atlantic, colonies of breeding seabirds and visiting migratory shorebirds fill the skies and waters and the crown-jewel is a glorious salmon river right in the middle of the city. In addition, as to be expected in Iceland, the geological heritage is rich, with lava fields, volcanic pseudocraters, glacial sediments and rock formations scattered through-out the city landscape. This rich nature is very accessible to the citizens, in easy walking distance for most.

Reykjavík has grown fast in the last decades, and only recently has the rapid sprawl of development been halted by city officials with focus on densification in the name of climate-friendly sustainability. While the positive environmental effect of this strategy is obvious, there has been a conflict when densification occurs in green spaces. One positive impact of the previously dominating sprawl city growth is that green spaces in Reykjavík are numerous and widely spread. Not nearly all are renowned parks or natural areas, some are nameless plots that happen to be vegetated and utilized by people living by them. Thus their use for densification has been protested and remains a contentious and difficult topic for the otherwise very “green-minded” politics ruling the city council.

A new city-run project called the Reykjavík Green Net aims to strengthen the status of the green spaces in the city, with focus on improving connections between green areas by adding various types of green infrastructure, walking and biking lanes as well as blue-green solutions for surface water runoff where applicable. Green spaces also feature highly in projects aimed to improve citizen involvement. “My neighborhood” is a citizen participatory platform where people vote for various features and events in their neighborhoods such as installations for sport and recreation. The vast majority of the features usually voted for are in green areas.

Reykjavík is well suited to be a National Park City—it has all the elements and already many projects that could fit in to this kind of premise. It could be a great opportunity for city officials to kickstart such a project and improve the dialogue about green areas. What makes the NPC concept so inviting is the creation of a platform of true partnership. But this could be its greatest challenge in Reykjavík. Despite there being no bounds to creative examples of collaboration in Reykjavík, there is a strong sense of independence in the typical Icelandic mind-set. Being told what to do, especially by politicians or officials, is never likely to lead to success. Therefore, the NPC concept would have to be introduced ground-up from community organizations, private or NGOs, even youth movements, to really gain traction. Following that, the city council would undoubtedly gladly support the idea.

about the writer

Maud Bernard-Verdier

Maud is a postdoctoral researcher at Freie Universität in Berlin, Germany. Her research spans community ecology, invasion ecology and evolutionary ecology, with a special focus on novel ecosystems.

about the writer

Aletta Bonn

Aletta Bonn is professor of ecosystem services and works at the German Centre of integrative Biodiversity Research. She is interested in the complex interactions of people and nature and employs participatory research methods, including citizen science.

about the writer

Sophie Lokatis

Sophie Lokatis is a phD candidate at Freie Universität Berlin. Her main interests lie in biodiversity research, urban ecology and education for sustainable development.

Maud Bernard-Verdier, Aletta Bonn, and Sophie Lokatis

Is Berlin already a national city park in everything but the name? Perhaps integrating such bottom-up initiatives into the overarching plans developed by city planners and experts may be what a Berlin national park would be all about.

While there may be cities with even larger areas of greenspaces, nature and urban wilderness are surely part of Berlin’s identity. It was always important for Berlin to keep urban parks as “green lungs” for air cooling and air pollution control as well as for recreation during times of enclosure by a wall. In addition, derelict railway tracks owned by the former GDR Deutsche Reichsbahn offered places for nature to reclaim their place during the Cold War times. Today, between its endless oaktree alleys and overgrown wastelands, urban life pulsates. It thrives, enlaced by meandering rivers and lakes, where on occasions dead fish and beer bottles wash up on the shore. Sometimes you will spot a kingfisher or catch a glimpse of a diving beaver. Berlin, indeed, has a great potential to become a National Park City.

A divided city grows together

Berlin’s history is unique, and so is its nature. This November (2019) marked the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin wall. Information plates on contemporary history alternate with those on plant and animal life along a 160km long cycle track around former West Berlin: the Mauerweg, path of the Berlin wall. In its central northern section, the Mauerweg connects an aggregation of half a dozen small to large scale parks and nature areas, mainly former railway areas and freight yards. These wild urban nature areas are invaluable—and novel—ecosystems. Whereas the distribution of green spaces in Berlin are usually highly correlated with socioeconomic status of the neighbourhoods, a fact that fosters environmental and ecological injustice among inhabitants, the Green Belt stretches right through the densely populated northern centre of Berlin, granting access to nature to residents of all income.

A capital of urban ecology science and grassroots movements

The Berlin Green Belt is a striking illustration of an urban planning that is rooted in a long tradition of urban ecology research in Berlin. The story goes like this: from 1961 to 1989, ecologists and naturalists in West Berlin, trapped behind the wall, turned to study the only nature they could access, thereby pioneering the field of urban ecology. Post-war Berlin was a pockmarked city whose many open abandoned areas and ruins welcomed a new growth of wild urban nature. Since reunification, reconstruction and rapid densification of the city has progressively reclaimed the green areas, but some remnant open spaces, such as the Mauerweg, have been actively protected.

The integration of nature conservation in urban planning goes back to the 1980s with the launch of the Landscape Program in 1988. This ambitious program was developed by leading urban ecologists such as Herbert Sukopp, in concert with landscape and city planners, originally for the isolated western sectors of the city. After the reunification of the eastern and western halves of Berlin, it was extended to encompass the whole city area and later joined by additional policies, including the Berlin Strategy for Biodiversity Preservation in 2012 and the Berlin Pollinator Strategy early 2019. What made the landscape program so special was that it was preceded by detailed ecological assessments of habitat types and went hand in hand with a strategy on biodiversity conservation. Therein, the Stadtbrachen—the wild, vacant and entirely novel ecosystems so typical for Berlin—were granted special conservation priority.

So, is Berlin already a National Park City in everything but the name? Some decades ago, efforts to transform the areas surrounding the city into a national park were halted when the population protested that they did not want live in a reserve. How would the citizens of Berlin welcome the whole city being granted special National Park City status? Berlin inhabitants have already demonstrated their strong commitment to urban nature and protecting open spaces. The recent community-led referendum to protect the Tempelhofer Feld is testament to the citizen’s wish to maintain wild and open places in busy urban centres—the former airport field is now transformed into a gigantic open grassland and recreational area, despite being situated in a sector with the highest increases in property values. There is a strong and growing commitment of Berlin citizens and environmental and conservation organizations to conserve and even restore urban nature within the city realms. In a time where many people are disconnected from nature, also termed “extinction of experience”, urban nature attains a special importance. Indeed, in Berlin we see a thriving, creative community garden scene, a rejuvenated interest in allotments by young and old, as well as movements like Mundraub to enjoy edible natural cities, many initiatives to promote insects, e.g. Berlin Summt!, or citizen science projects such as the NABU Insektensommer to reconnect to nature by learning-by-doing.

In addition, nature-based solutions to climate adaptation, such as air cooling through street trees and other larger urban green and blue spaces, will be essential to safeguard citizens in a warming climate. Already, we can see a striking urban heat island effect with differences of up to 10°C in hot summer nights from Alexanderplatz to Grunewald, and promoting urban green and blue spaces can contribute to a climate resilient city. In addition, urbanisation has been linked to a rise in mental health issues, such as depression, and biodiverse urban nature can serve as a natural medicine—it will be important that citizens can actively enjoy nature in their daily life.

Perhaps integrating such citizen-led bottom-up initiatives into the overarching plans developed by city planners and experts may be what a Berlin national park would be all about? Berlin could set an example how daily life can be linked with nature. Conservation of our city nature would serve as active investment into the liveability of Berlin—ultimately a National Park City would not only enhance biodiversity but also public health and wellbeing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p-VHOrC5a9Q

about the writer

Samarth Das

Samarth Das is an Urban Designer and Architect based in Mumbai. Having practiced professionally in Ahmedabad, Mumbai, and subsequently in New York City, his work focuses on engaging actively in both public as well as private sectors—to design articulate shared spaces within cities that promote participation and interaction amongst people.

Samarth Das

Even though Mumbai is one of the few cities in the world that has a National Park within the municipal limits of the city, we argue that instead of having one “Central Park” in the city that everyone travels in order to access and enjoy, having smaller and more accessible neighbourhood parks promotes healthier and active lifestyles. This is why the London National Park City initiative is such an exciting prospect.

Unfortunately, owing to unplanned and ad-hoc development, these natural features and assets have been neglected, abused, and misused, thereby rendering them as backyards. Even the city’s development plan has failed to recognise the importance or potential of these natural assets. Apart from their undisputable role in protecting and shielding the city from in-land flooding, sea level rise and storm surges, these natural areas can be integrated into the neighbourhoods to become the forefront of public realms that are accessed, enjoyed and protected by one and all.

Picture this: Preservation programs such as those in Jamaica Bay (New York), nature trails through biosphere reserves like those in Sian Ka’an in Mexico, walking and cycling paths along the canals of Amsterdam, boardwalks of KRKA National park in Croatia, leisure and recreation opportunities seen in Central Park in New York City and Hyde Park in London; remediation of water bodies like the ongoing efforts in Gowanus Canal in New York city; along with outdoor classrooms promoting active learning through planting programs and nurseries, bird viewing galleries along wetlands; and programs engaging locals in art amongst other means of interacting with their natural surroundings. All of these would constitute integral elements of a larger vision of Mumbai as a National Park city, a vision constantly under works and one that is continuously evolving.

Through our professional practice, PK Das & Associates, and several of our community-led initiatives, we have successfully implemented neighbourhood-based projects in the city that aim to achieve precisely these objectives. The Irla Nullah Rejuvenation Project in the western suburb of Juhu in one such project which aims at re-appropriating a neglected and dirty open storm water channel into an accessible public space with several parks and gardens along its edge, thereby bringing the several communities that live along it together geographically as well as programmatically. We hope for many more such initiatives across the city.

In Mumbai the primary challenge has always been the enforcement of policies and ensuring the safeguarding of our natural areas. With the city unable to provide adequate housing and cope with the speed of population growth over the years, informal settlements sprung up in the most neglected areas of the city—which most often tend to be the edges and buffers of these natural areas. The idea of the National Park City concept demands attention to not just our natural areas, but also a more comprehensive and holistic approach that integrates infrastructure solutions for housing and amenities with neighbourhood based planning, builds in new non-motorised modes of transport into our mobility plans, and most importantly, creates a transparent and open platform for local advocacy groups that can demand definite time periods for responses/ actions taken by local and state machinery to address grievances and complaints. Nature, in our city, is in an advanced state of degradation and it is an immense challenge to reconcile with and rejuvenate these sensitive ecosystems in order to bring them back to their past glory.

Even though Mumbai is one of the few cities in the world that has a National Park within the municipal limits of the city, we argue that instead of having one “Central Park” in the city that everyone travels in order to access and enjoy, having smaller and more accessible neighbourhood parks promotes healthier and active lifestyles. This is why the London National Park City initiative is such an exciting prospect: it allows for every individual, regardless of age and gender, to participate equally in their surroundings while also being able to voice their opinions when needed!

about the writer

Ana Faggi

Ana Faggi graduated in agricultural engineering, and has a Ph.D. in Forest Science, she is currently Dean of the Engineer Faculty (Flores University, Argentina). Her main research interests are in Urban Ecology and Ecological Restoration.

about the writer

Sebastian Miguel

Architect and Master Architectural Design (University of Buenos Aires). Director Bio-Environmental Design Lab (University of Flores- Buenos Aires). Professor and researcher at Catholic University of Salta (UCASAL). Principal at Sebastian Miguel Architects & partners (Buenos Aires). Member of Argentinean Association of Renewable Energies and Environment (ASADES)

Ana Faggi and Sebastian Miguel

Even if efforts were made to increase public green space, the surface area of green would not be sufficient to house populations of native fauna. That is why we believe that the National Park label would be inadequate.

Going back to reality, if we take the case of the green infrastructure, the quantitative deficit of total area of public green space per inhabitant is known and also poorly distributed. Official statistics say that there is an average 6m2 while international standards set minimums of 10-15 m2 (WHO 2012).

Many of these green areas have insufficient vegetated and absorbent soil, and the vast majority of the vegetation that we find in squares and in the trees along the streets of Buenos Aires is exotic. The absence of elements of the typical Pampas vegetation limits the presence of the possible 200 species of birds and 100 species of native butterflies that we could observe in the original landscape.

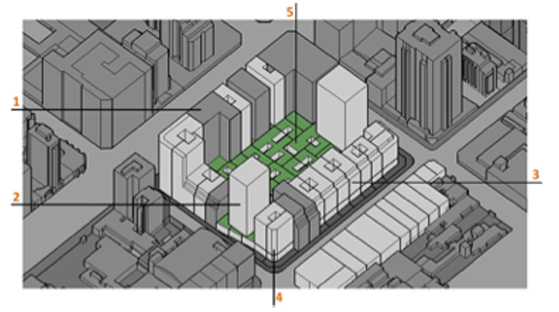

In Buenos Aires, by the late nineteenth century, green spaces began to be relevant urban areas in social life. Large public parks arose under the influence of French and English landscaping models, coinciding with the hygienist movement in its attempts to relieve the burden of urban living. Many private gardens have low biodiversity and are getting smaller and smaller, as single-family homes are demolished to build multistory buildings (image below).

Even if efforts were made to increase public green space, in the areas that are generated today by coastal filling in the estuary of the Rio de la Plata, or creating new parks on vacant areas of the railroad, the surface area of green would not be sufficient to house populations of native fauna. That is why we believe that the National Park label would be inadequate. However, visioning the future, we could strive to reach situations that could be framed in a conservation figure such as a Nature Biosphere Reserve with cores of greater conservation value that dissipate towards the edges. This would be a chance for the city to understand and manage changes and interactions between social and ecological systems what is currently missing.

Biosphere reserves are areas comprising terrestrial, marine, and coastal ecosystems, promoting solutions that reconcile the conservation of biodiversity with its sustainable use. As defined by United Nations they have three interrelated zones that aim to fulfill three reinforcing functions:

The core area is devoted for the conservation of landscapes, ecosystems and species.

The buffer zone surrounds or adjoins the core areas, and is used for activities compatible with sustainable practices and a transition area where the greatest activity is allowed.

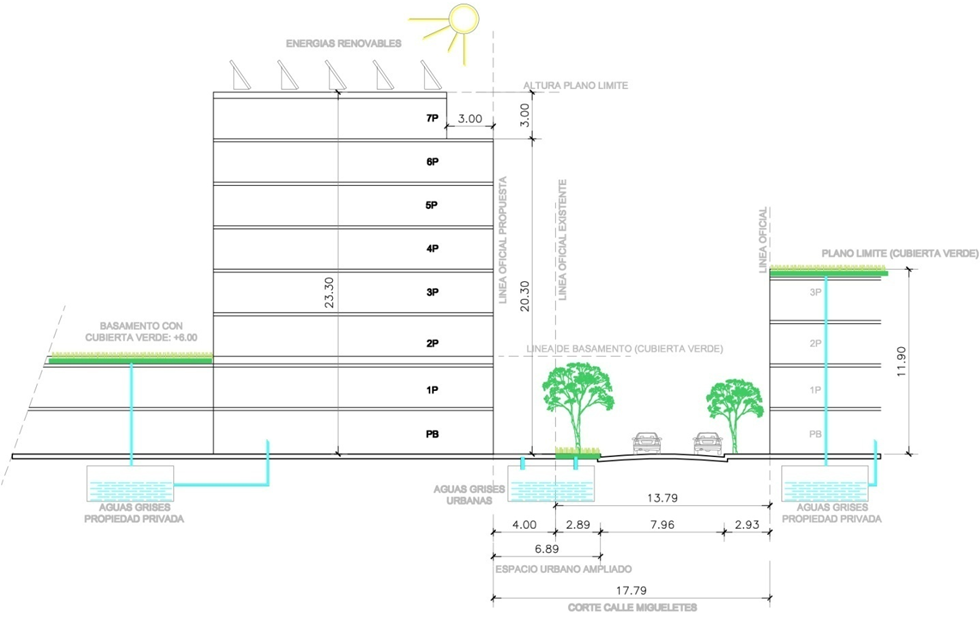

In Buenos Aires, the current trend that raises the new building code is to increase the built surfaces in a compact and high way. To increase green infrastructures, this height development should require that new buildings in both the public and private domain have a greater proportion of internal courtyards with absorbent and green surfaces that mitigate the effects of climate change and become local biodiversity shelters. Vegetation of terraces and walls should be added.

In turn, the city should allocate the hundreds of thousands of square meters of sidewalks and public urban interstices that have the possibility of becoming absorbent soils, small landscaped spaces and green corridors. They should also consider that part of the remaining sites could become re-wilded, areas that are still very little present in Buenos Aires, as we described in a previous roundtable. This would significantly improve the environmental conditions of the city, especially in the pedestrian and at the neighborhood scale.

At the ground level of a city block, the transition zone built up by green corridors, absorbent surfaces and walking and bike roads, can encourage mixed uses programs. At the high level: canopies of trees and green urban roofs, crossed ventilation and exposure buildings to sunlight can mitigate heat. At the underground level, the development of urban infrastructures as water storage and parking may create a better city for pedestrians (image below).

In coincidence with the ecological urbanism mentor, Salvador Rueda, who proposes to create ecological urban links at the three levels of a neighborhood, we believe that the idea of a Biosphere Reserve is possible (image below).

Reference:

World Health Organization. Health Indicators of Sustainable Cities in the Context of the Rio+20 UN Conference on Sustainable Development. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2012.

about the writer

Scott Martin

Scott has worked for over 25 years on urban park and conservation teams across the United States. He is presently Director of a Louisville (Kentucky) regional NGO at work creating a new 600-acre urban park system on the banks of the Ohio River. He also serves as a board member with World Urban Parks.

Scott Martin

Perhaps in the National Park Cities framework we will find the vocabulary of shared values necessary to address the urgent urban ecological and health crises that elude, frustrate, and imperil us all.

Given these seasons, the incredible diversity of plant and animal species found throughout our forests, and the wonderful Fredrick Law Olmsted-designed system of parks and parkways throughout the city, my neighbors and I should be among the most active and “nature aware” urban residents across the globe. This is not the case.

The Trust for Public Land’s 2018 Park Score ranks Louisville #81 out of the 100 largest US cities for the four characteristics of an effective park system: access, investment, acreage, and amenities. Because of high heart disease and diabetes rates, conditions that are closely related to obesity, Louisville was ranked the fifth-unhealthiest city in America by the American College of Sports Medicine. Perhaps most dangerous of all may be our urban heat island. In 2012, Georgia Tech University analyzed urban heating in the fifty largest cities in the States, and Louisville came out on top—above even Phoenix. Phoenix created a city in a desert. We created a desert in a forest.

Our inability to mobilize solutions to these known challenges, acknowledged across the political spectrum, suggests that is isn’t our leaders’ fault. The fault lies in our imagination. We need a new approach. Thus, the National Park Cities provocation matters.

Our inability to mobilize solutions to these known challenges, acknowledged across the political spectrum, suggests that is isn’t our leaders’ fault. The fault lies in our imagination. We need a new approach. Thus, the National Park Cities provocation matters.

The implementation of a National Park Cities framework introduces a new vocabulary for place; it provides us with a “string theory” for the urban ecosystem. It provides language that people can understand and quickly personalize. This new vocabulary may allow us to outgrow the adolescence of urbanization where we fought so hard to separate the built from the wild.

So, what could happen if my city became a National Park City? What would be different if we woke up one day with the awareness that we share a special, valuable, and unique urban green space?

- We listen to the wisdom of our elders and the traditional owners who thrived here.

- We celebrate the annual return of migratory songbirds and understand with whom we share them.

- We sustain space for wildlife and healthy corridors for people.

- We walk and bike more.

- Our private development and public conservation communities collaborate to green our cities, neighborhoods, and urban core.

- We thoughtfully give our waterways room they need to flood.

- Our students learn about oaks.

- Our rich and diverse bodies of faith strengthen their believers’ connection to Creation.

- Our burgeoning tech sector deploys platforms that engage people daily with the outdoors just out their doors.

- Our couches and gyms empty. Our parks and trails fill.

- Nature is reflected in the work of our visual and performing artists.

- We demand good answers to questions like, “What if the Ohio River was clean enough to swim?”

- Local proteins and produce are found in our home kitchens, restaurants, schools, and senior centers.

- Local plant stores and nurseries sell native plants that sustain our wildlife.

- Any citizen from any community can register for any recreation program in any city.

- We build aerial highways for flying squirrels through our neighborhoods.

- We demand buildings with windows that open.

- We intentionally incorporate time outdoors into every single day of the year.

- We make space in our yards, parks, and buildings for wildlife. We then experience their stories of life, and death.

- In doing so, we recover small bit of our humanity.

- We make the choice to be better than we were.

We inspire the youngest among us to do more than we ever did.

We inspire the youngest among us to do more than we ever did.

Could Louisville become a National Park City tomorrow? Certainly. I believe our local elected officials would sign the charter as presently written. We would also see short-term rallying to the cause. However, I don’t believe this will be enough.

The Charter challenges us to recast our thinking, our expectations, our understanding of interdependence, and our accountability to one another to deliver lasting change. Organizing ourselves to its objectives across diverse city landscapes requires changing what it means to build, operate, live in, and sustain our very urban (and nature-divorced) lives.

Frankly, I don’t know if my city is ready for that leap. While the signatures will be easy, finding the ability to foster, in a culture that celebrates consumerism and industrial-level consumption, the awareness and vulnerability necessary to sustain stewardship and collective accountability to the Charter’s objective will be much more difficult. And that’s ok because real, lasting, big change should be hard.

The National Park Cities idea, as now expressed in the Universal Charter, provides the framework, a vocabulary if you would, that elevates the possibility of what our urban environments can do to support healthier people and sustainable ecological communities. That these values are shared in cities across the globe only strengthens my resolve that this work matters.

We now have the map. Will we take the journey?

about the writer

Julie Procter

Julie Procter is Chief Executive of greenspace scotland. With over 25 years’ experience working in the environmental sector, she is passionate about the importance of greenspace close to where people live and the many benefits it delivers for people, places and communities.

Julie Procter

In Scotland, we already have a strong and supportive policy framework. We now need the ambition, imagination, and confidence to think and do things differently, to break out of traditional sector and organisational silos, to work in ways which are collaborative and empowering.

Our parks and public greenspaces will no longer be caged like animals in a zoo. Green fingers, fronds and tendrils will reach out across the city, as street trees, rain gardens, green roofs and walls colonise our streets and neighbourhoods.

Children will no longer be imprisoned in classrooms and nurseries. Every day they will enjoy and be inspired by learning and playing outdoors and experiencing nature at first hand.

Local food growing will break free from the shackles of allotments and soon we will be sowing and growing everywhere—from pop-up gardens at the bus stop and vertical growing up the office wall, to edible playground planters and tasty community street orchards.

Commuters will be liberated from the cars as walking, cycling and active green travel is now the easiest way to get around the city.

Escaping from the car we will connect again at a human scale—noticing the flowers blooming, the wind blowing through the leaves, the sweet sound of birdsong and breathing clean air.

Communities will no longer be entangled in red tape when they want to take action to make their homes, streets, and neighbourhoods cleaner, greener, and healthier or simply enjoy a community event in their local park.

Once again, we will enjoy the sight and sound of children playing outside…and make time to stop and chat with neighbours and friends.

All of this adds up to a greener, healthier, happier city where people, places and nature are better connected, where communities thrive and we all enjoy longer lives, better lived.

Realising the ambition of a National Park City is as much about changing mindsets as it is about changing the fabric and the infrastructure of the city

In Scotland, we already have a strong and supportive policy framework where national outcomes are aligned to the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Our national outcomes include: people value, enjoy, protect and enhance their environment; people live in communities that are inclusive, empowered, resilient and safe; people are active and healthy.

Research already provides a strong and growing evidence base on the multiple benefits of green and blue space for our health, communities, economy and environment.

We now need the ambition, imagination and confidence to think and do things differently, to break out of traditional sector and organisational silos, to work in ways which are collaborative and empowering. We need to be bold and ambitious about how we want to live our lives and shape our cities.

Then we can realise a Scotland that is a nation of National Park Cities, where our green and blue spaces are our natural health service, our children’s outdoor classrooms and our cities’ green lungs.

about the writer

Rob Pirani

Robert Pirani is the program director for the New York-New Jersey Harbor & Estuary Program at the Hudson River Foundation. HEP is a collaboration of government, scientists and the civic sector that helps protect and restore the harbor’s waters and habitat.

Rob Pirani

The US National Park Service has a planning process for managing national parks. It is founded in purpose, significance, and fundamental resources and values. Can New York articulate these elements? Absolutely.

London calling! And their bold declaration promises that considerations of nature in the whole will elevate all the fragmented bits and pieces in our midst. The idea of a National Park City makes for a wonderful and I believe effective campaign and marketing strategy. And it encompasses a host of sound landscape conservation and recreation management practices as well. The trick of course is getting the specifics right.

To think about how application of the National Park City idea might play out in New York, I turned to the planning process deployed for management of National Parks in the United States. The four steps deployed by NPS are to identify the park purpose, its significance, the fundamental resources and values that speak to that significance, and the interpretive themes that will resonate with visitors. To be clear, the mandate is not the same and the analogy not perfect. But the premises and process used by the National Park Service offer the right questions for anyone seeking to improve and celebrate place.

So here are my considerations for nominating New York as a National Park City (with acknowledgement to the recent Management Plan established for our local Gateway National Recreation Area):

The park purpose is a specific reason why a park was established. The National Park Service starts with the premise that that units of the national park system reflects the diversity of the nation and that, as a whole, the National Park System tells America’s story through these cultural and natural resources. The purpose statement provides the most fundamental criteria against which the appropriateness of all planning recommendations, operational decisions, and actions are tested.

Any city can offer testimony to its own purpose and role in shaping a nation’s character. Here is an appropriately modest one for New York:

Park Purpose:

New York City is the heart of the nation’s largest metropolitan area, regional economy, and cultural center. Its forests, beaches, marshes, waters, scenic views, and other public spaces offer critical habitat and resource-based recreational opportunities to a diverse public. Its parks and public spaces include notable examples of the most significant design and management innovations of the last 200+ years.

Statements of significance define what makes the park/city unique—why it is important enough to warrant designation as a park and how it differs from other places. These statements are tools for setting resource protection priorities and for identifying appropriate experiences. Every park—and every city—contains many significant resources, but not all these resources contribute to why the park/city might be designated. The notion is to identify three or four statements that capture the essence of a place.

Here is one example that—again immodestly—captures one feature makes New York as Park significant. My own thinking is that this would be one of four statements; the other defining characteristics of New York National Park City would be Recreational Resources for a Diverse Population; Streetscapes and Urban Mobility; and Parks and Public Space Innovation.

Significance Statement: Ocean & Estuary

New York City lies in one of the world’s greatest estuaries. The interaction of the Hudson River and Atlantic Ocean support an important assemblage of coastal ecosystems, including oceans, beaches, barrier islands, bays, tidal rivers, and maritime uplands. The habitats and rich biota that compose these ecosystems are rare in such highly developed areas. These features provide opportunities to restore, study, enhance, and experience coastal habitats and ecosystem processes for a diverse urban population.

Fundamental resources and values are the park/city’s attributes—its features, systems, processes, experiences, stories, opportunities for visitor enjoyment, etc—that are critical to achieving the park’s purpose and to maintaining its significance. These fundamental resources provide a focus on what is truly most important, and where to focus effort and funding.

Relative to the significance of its Ocean & Estuary, New York City’s fundamental resources and values are the variety of coastal and estuarine ecosystems and the most important places and habitat, like the Rockaway Peninsula or the lower Hudson River. But it should also include unique experiences like walking on a sandy beach, kayaking down an urban stream, or witnessing the spring migration of fish and birds.

These resources and values are communicated through the park’s interpretive themes. These themes are based on the park’s purpose and significance and connect resources to relevant ideas, meanings, beliefs, and values. They describe the key stories and concepts on which educational and interpretive programs are based. Here is one drawn right from the Gateway Management Plan that might also fit New York City as whole:

The Natural Wonders, Dynamics, and Challenges of an Urban Estuary.

The natural resources of [New York City] are remarkably diverse given their location in the nation’s most densely populated urban area. The mosaic of coastal habitats is a refuge for both rich and rare plant and animal life intrinsically governed by the rhythms, processes, and cycles of nature, yet also continually shaped by people and the surrounding built environment. These resources provide unique and surprising opportunities for experiencing the wildness of the natural world while within the city’s limits, and a model for studying, managing, and restoring urban ecosystems.

It is easy of course for one person to get through this four-part test; not so simple for a room (or city) full of diverse and valid opinions.

So, back to our prompt question: Would management of New York City’s natural and cultural resources truly enhanced by considering the city as whole?

I think so. Considerations of the whole City frames decisions and investments in ways that speak to ecological process, whether it is watershed conservation, creating connective greenways, or restoring guilds of representative species. Creating personal experiences that speak to whole city landscapes—like art that celebrates buried watercourses or massive, collective citizen science efforts that capture a day in the life of the Hudson River—can help reveal nature in our urban midst. The challenge would be defining which processes, and which experiences, are most important to elevate.

about the writer

Timothy Blatch

Timothy is an urban development professional with a background in the social sciences and city and regional planning. In his role as a Green City Consultant at AIPH, the world’s champion for the power of plants, Timothy is responsible for progressing strategic partnerships within the Green City programme and for coordinating the AIPH World Green City Awards.

Timothy Blatch

The more I consider the idea for Cape Town, the more I see its potential to provide an umbrella under which actions by a diverse range of stakeholders can increasingly contribute to co-shaping a collective urban future that is rich and sustainable.

When I first heard about the idea, it seemed an exciting next step for developed cities who are already committed to living in harmony with nature. But I was certain it would be impossible to replicate in the African urban contexts within which I am more accustomed to working.

As a Zimbabwean living in Cape Town, the concept simply did not seem transferrable. This was partly because open spaces, and even urban parks in the cities I have lived in have never been places that have typically been desirable for urban residents. In many cities in Africa, parks are crime magnets and are generally perceived as unsafe and undesirable. Their value in urban quality of life and human wellbeing is poorly understood and horribly taken for granted. Furthermore, the maintenance of these spaces has also typical been neglected, rendering them forgotten remnants of an inherited urban form that are fast disappearing under the pressure for development.

However, the Cape Town example is an exceptional one, in the sense that it is already a national park city, although not in the same way London now proudly defines the movement. The City of Cape Town has historically developed around the perimeter of the base of Table Mountain National Park. Table Mountain rises prehistorically at the heart of the city, and is home a large part of the unique, abundantly biodiverse, and largely endemic Cape Floristic Kingdom that the region is famous for.

However, the Cape Town you see in the picture above is only a small part of the city’s story. The majority of the Cape Town population are still affected by the racially motivated spatial dynamics that were characteristic of the Apartheid era, and do not enjoy the same level of access to the city’s rich natural resources. You see, the majority of the city’s population do not live in the areas the picture above depicts, and many still live in less than favourable conditions, with little access to even the most basic of services.

However, the Cape Town you see in the picture above is only a small part of the city’s story. The majority of the Cape Town population are still affected by the racially motivated spatial dynamics that were characteristic of the Apartheid era, and do not enjoy the same level of access to the city’s rich natural resources. You see, the majority of the city’s population do not live in the areas the picture above depicts, and many still live in less than favourable conditions, with little access to even the most basic of services.

With much competition for a diminishing public fiscus, trade-offs are essential and the provision of housing and sanitation are understandable priorities. The idea of igniting a wave of change around a contextually nice-to-have concept only seemed possible among a small percentage of the more affluent Cape Town population. Pitching the idea to the critical mass necessary to meaningfully say there was sufficient buy-in to a national park city in the way London, and the Universal Charter define it, seemed a futile exercise in the face of the reality that faces many Cape Town residents.

So, although Cape Town has a number of national parks within the metropolitan boundary, it is only a national park city in so far as the protected areas legislation defines it to be, and not necessarily in the socio-ecological sense. Coupled with this is the fact that the very notion of a national park has a complex history in South Africa and the very word “national” has loaded contextual implications for local implementation.

As I started to become more familiar with London’s ambitious vision, I was encouraged by its flexible nature and bottom-up approach. Even though I am certain that it would look very different in the South African context, my thinking has evolved in the sense that a vision for a greener, wilder, and healthier city is a vision that every city should strive to achieve.

I spent many hours wondering and dreaming of how this concept could be made a reality in Cape Town. It would take a lot of awareness-raising. It would take years of work to mainstream nature-based solutions and build the capacity for strong governance and prioritisation of nature. It would take public participation and collaboration on a massive scale. It would take a whole-of-society approach that we often talk about, but somehow defies our best efforts to achieve.

However, more and more, I am convinced that it is possible. The more I explore the city, the more I am awakened to the many initiatives that are taking place to bring nature into the daily experiences of residents. Small collective action has the power to trigger large scale impact, and I am constantly reminded of this through my work with cities around the world. The national park city movement has certainly triggered a longing for what may be possible and has stirred up interest in the idea of experiencing nature all around us in our urban lives. Nature has the power to transform our cities, and the need for transformation is critical in Cape Town.

The more I consider the idea for Cape Town, the more I see its potential to provide an umbrella under which actions by a diverse range of stakeholders can increasingly contribute to co-shaping a collective urban future that is rich and sustainable. The concept has every likelihood of succeeding in the long-term, only if we are able to ensure just and equitable access to nature and its benefits in Cape Town. Similarly to how my approach to the concept has shifted favourably over time, I hope that with sufficient investment, will, and passion, the readiness to achieve such an ambitious vision might shift favourably, too, in South African cities. In the same way that we protect the Kruger National Park to ensure the highest quality habitat for the species who call it home, surely we should also aim to ensure our human habitats, which are increasingly urban, are healthy places for us to live and thrive in. The national park city concept offers us a solution, and London has demonstrated that it is indeed possible to achieve.

about the writer

Lynn Wilson

Lynn Wilson (MCIP, RPP) is a regional park planner for a 33,000-acre natural area system on Southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada.

LynnWilson

Daniel Raven-Ellison made it happen for London, but each city will need its own leader(s) to emerge who can inspire and motivate enough people to make it happen in their particular circumstances. Who?

While the pull of becoming a National Park City will certainly be strong for many global urban centres with already well-developed green and blue infrastructure, there are serious things to consider before going down this path. One that immediately pops out is the value that a city might place on being identified as a “national park” city—with its inherent identity politics in relationship to a federal government. While we may think that national park systems elicit inherently positive attitudes, this may not be true in every circumstance. Not all citizens have a positive view of their national governments, and the idea of giving the national government “credit” for the best parts of their city by branding it as a National Park City might not sit so well with some. Along those lines, many communities, cities, and regions possess a strong sense of “local” with already well-developed global brands that work for them. In such cases, will the layering on of a National Park City label only serve to dilute these well-established identities?

Another very important consideration about becoming a National Park City is the fact that each city will need a “champion” like London’s National Park City idea originator, Daniel Raven-Ellison, who worked tirelessly for years to bring about his vision. His success is inspiring for so many, but it shows that to become truly successful, a National Park City requires vision, time, commitment, energy, resources, as well as a bit of luck and magic to make it happen. Daniel Raven-Ellison made it happen for London, but each city will need its own leader(s) to emerge who can inspire and motivate enough people to make it happen in their particular circumstances.

It is clear from the London National Park City website that key components of realizing their vision includes the creation of a governing charter, the establishment of a partnership (comprised of groups and organizations) led by a steering group, and the development of a foundation to provide the leadership, fundraising, partnerships, and administration necessary to undertake the day-to-day work to keep it all going—which is to say that a lot of hard work and persistence are required to see this through. A key question for those considering joining this movement is the extent to which this necessary formula can successfully be replicated elsewhere?

That being said, and on balance, I truly believe it is worth endorsing the idea of National Park Cities because the vision is so compelling and timely, the motives for undertaking the work are so pure, and the potential benefits so critical to the continued health and well-being of humans and nature alike. After all, who wouldn’t benefit from living in a healthier, wilder, and kinder city of the type promoted by the National Park City movement? To this end, I, for one, sincerely hope that 25 cities will find what it takes to become a National Park City by 2025.