about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

Everyone, no?

But not everyone has access to the myriad benefits of green. The world over, north, south, east, and west, green and its benefits for resilience, sustainability, and livability tend to concentrate in wealthier areas. How might we start to face up to and act upon the idea that access to urban green in a right made available to all? This was one of eight TNOC Summit Dialogues in Paris in 2019.

At TNOC Summit, we largely avoided long presentations in plenary—i.e. “Keynotes”. Rather, we gathered for eight “Dialogues”, similar to the Roundtable format at TNOC. For each dialogue there was a core question or prompt, such as the one in this Roundtable. We invited three people to participate, striving for a multi-disciplinary group, with diverse points of view, perspectives, and approaches. Each of the three delivered a short intervention (6-8 minutes), and then sat together for a longer conversation.

In this Roundtable, with Isabelle Anguelovski (Barcelona), Adrian Benepe (New York), and Samarth Das (Mumbai), we present both their written texts and a video of their presentations. Also below you can find a transcription and video of the conversation below.

A transcription of the conversation

David Maddox (Moderator): Does everyone in this room believe in the benefits of green space?

Raise your hand if you believe in the benefits of green space. Very good, then who gets to enjoy those benefits? Does everyone get to enjoy those benefits? No, they do not. So, the two big threads in this conversation. One is about the developed World. Lots of parks. And the other is places like places like Mumbai and many other places not only in the global South, but often the global South, which have very few or no green spaces at all. So I think there are two threads that we want to talk a little bit. The first one is to riff a little bit on what Adrian and Isabelle were talking about, how if we believe in the benefits of green space and we are trying to create a brilliant program like 10 minute walk to a park, which is very consistent with the what they’re doing in India as well, how do we break a cycle between the benefits of the creation of green space and gentrification and displacement. How do we break this pattern?

Adrian Benepe (Senior Vice President, The Trust for Public Land, New York): It’s a question that we’re actually wrestling with now, we got some money to do some studies. There’s very little actual good data on this. There’s a lot of data about it that lacks any direct conclusion about causation. There’s a lot of correlation, but it’s as we dig into it the causation becomes a lot thinner, because you also have to look at other things like the development of mass transit lines and all the other things that lead to gentrification.

Soho and Tribeca in the West Village of New York gentrified well before parks were added there. These were these are communities absolutely without parks, so the forces behind gentrification and particularly the impact of gentrification which is displacement are varied and complex. However, that said, what we have learned is that it is not an either/or but a but/and. If you’re particularly going to be doing large-scale park development, you have to look at the potential impacts and look at how can we ally this with affordable housing development or making sure that you keep permanently affordable housing there. There are homeowners who love the idea of gentrification because the value of the property goes up, the renter’s not so much. So again, you have both sides.

So, what we have learned finally in the park creation business is it’s not just a park. It’s going to have a ripple effect and, exactly as you say Isabelle, you have to look at how do we combine this park with mobility, with affordable housing, and all the other things that make a holistically healthy community a park by itself won’t do that and it could have, as you point out, unintended consequences.

Isabelle Anguelovski (social scientist, justice advocate, Barcelona): I couldn’t agree more and the causation really requires spatial analysis methods that are very complex, and that are really important because otherwise, as you say, you cannot really parse out the role that green space plays in in gentrification. That said, I think that we also seeing is really some progressive mayors, like I would say our mayor in Barcelona, the mayor in Nantes, really embedding considerations of gentrification in every possible policy that they think about, that is related to land use, so they have special working groups, they have committees, they have almost like a gentrification impact assessment, if you will, which I think is a really smart way to think proactively about it. Cities like Washington DC also have Innovative models. For instance Community Land trust’s are quite popular in the United States, but very difficult to fund. I think regulations also very important like the inclusionary zoning aspect is key. The amount of affordable housing is key.

But you often have mayors who are elected having real estate developers in their pockets, and now real estate development is what drives growth in cities, both economic growth and spatial growth. So, if you don’t have a decoupling between urban agendas and who funds cities and at the same time growth in the city, I think you are going to keep having these gentrification effects, which as I was trying to highlight, really does not only concern lower income and minority residents, but also increasingly concerns the middle class. And it’s shifting. It’s like Boston gentrifying Washington DC because most people can’t afford to live in Boston, now DC becoming so expensive people go to Philadelphia, and now Philly…you know, there’s kind of this rotation around the country. It’s really in the end is kind of a national crisis

David: And Mumbai has a fraction of the green and open space that even New York. New York is a very dense City, but Mumbai has a tiny fraction of what New York has how do you respond to these kind of conversations?

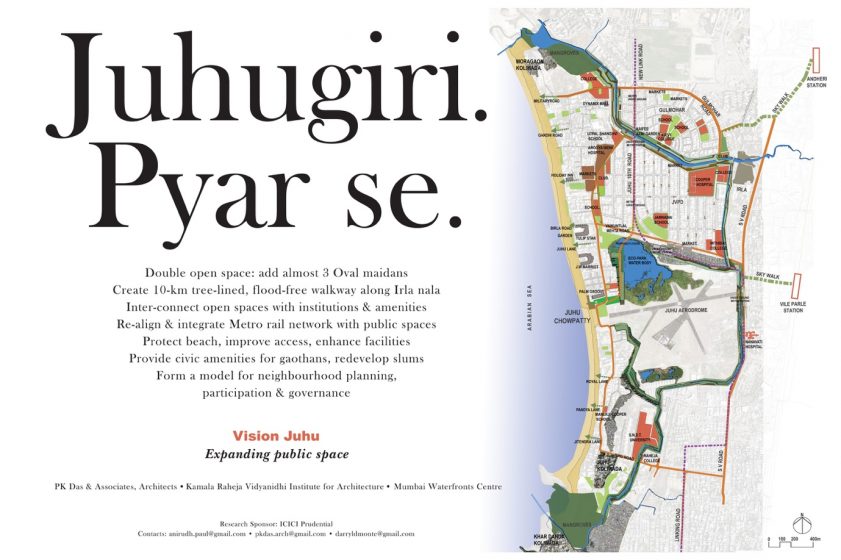

Samarth Das (architect, Das & Associates, Mumbai): To give you the exact figure, the open spaces ratio to number of people in London is 31.68m2 of open space per person. It’s about 26.4m2 per person in New York. In Mumbai, it’s 1.1m2. So, we really don’t have any parks or open spaces when you look at our population density. That’s based on the data in the year 2000, and it’s probably even worse right now. (Source: Vision Juhu – Expanding Public Spaces, 2009, http://pkdas.com/published/juhu-book-final.pdf)

So yes, we are dealing with very different contexts. But the important thing for me is in the process of developing the park and then considering its ripple effects of gentrification, it’s important who’s developing the park. In Mumbai, what we have managed to do is really integrate even the small pocket parks, really integrate and build the process from ground up. I give you the example of some of the parks that I showed in my talk, those parks when undeveloped had illegal activities, drug peddling, but during the daytime you had kids from the slums coming there and playing. It depends who owns the park. Once we developed the parks we’ve ensured that it still be accessible to the kids from the slums. Still have access to those parks. Sonow they have started learning how to use these spaces, because they’re not used to have such spaces. So, initially we are faced with issues of vandalism, of theft. These are some things that communities push back against and then push for exclusion of certain groups of people, but we’ve managed to build that sense, a ground up network. Governance is very important.

And then in Mumbai—I don’t know the situation the other cities—but we have privately owned parks and publicly owned parks. And some of the parks that we’ve developed. In fact, the citizens fought against land-grabbing developers who had snatched land for real estate profits. You had the community mobilizing; you had almost 15,000 people at the gates to the park standing to oppose. We fought in the Supreme Court. So, the people get invested in the process. And then once the Park comes to life, there’s a sense of ownership, of belonging and, of course, maintenance that comes with it.

So, in Mumbai people are yearning for open space, we’re all crying out for some sense of open space. So, unfortunately—or fortunately—we’ve not reached the situation where we have to worry about gentrification that comes with parks, but for now, we want to make more parks.

David: If you applied the 10-minute walk to a park metric that Adrian described in Mumbai, we know what the answer would be it. Could you imagine though that if you applied such a metric in Mumbai, it could be a political tool, as Adrian described, that you could use it as a motivator for leaders and mayors, because they start to look bad? Could you imagine doing that?

Samarth: Well, absolutely. And in fact, that’s precisely what we use to leverage getting some support. We work actively with elected representatives from the government. There are politicians who sometimes very insensitive to the ideas of greening and improving public space and more importantly ensuring access to public space. But we’ve been blessed over the last five or seven years with very active members of the legislative assemblies, along with the officers and the bureaucracy who see the benefits and then support this process.

It is why we focused on the nullah project, because of the importance of scalability. We have 250 kilometers of waterways within Mumbai. In fact, we took this project to the City of Mumbai and the commissioner gave us permission: “All right, here you go, 1.2 kilometers. This is your pilot you have to find funding for it because we don’t have it. Let’s see if it’s successful and then we can Implement that across the city” … and of course everyone jumped onto that opportunity. So now the members of legislative assembly who supported the project already recognition in the city for doing something that has not been done anywhere in the country. Now there are people who piggyback on a process, and then it’s really how we stitch together those collaboratives to make something successful. It’s highly localized, even across the several projects that we worked on. The approaches have been very different, based on the different communities that we’ve been interacting with.

David: Isabelle, do you find the metrics like this to be positive political tools to promote the idea, not only of more parks and access to green space and their benefits, but also as a forum to discuss some of the negative things that you talked about: gentrification and displacement?

Isabelle: Yes, and I think certainly so especially as some cities are focusing on universal access to green space rather than addressing equity. And I think the example of Nantes is very good in that sense. Unlike for instance what Los Angeles has been doing, which is more to map where communities have least access to green space and then to motivate private developers to contribute to a fund, and that then will be used to create new green space around the city … except that this fund is actually going to other communities. So, at the end of the day you have new real estate development in low-income communities that don’t have green space, and the the communities that already have green space have it more. So, I really like the tool of universal access. It’s important.

Adrian: I was really interested in what you said, Isabelle, about the issue of gentrification impacts not just on poor people, but also middleclass people. We had a project in Bozeman, Montana. Bozeman is a small city of 30,000 people, but it’s doubled in population over the last 10 years. It’s going to double again, and we are creating the Central Park of Bozeman. It’s a 60 acre park, which is a big park for Bozeman, right downtown. We were able to carve off eight acres to be set aside for affordable housing. By Bozeman standards affordable didn’t mean for poor people, it meant for teachers, firefighters and others so they didn’t have to live 30 miles outside of town and have a big commute in. And it was also guided by local zoning, which turned out to be really difficult because the local zoning was for single family homes, affordable single-family homes. There isn’t a developer of affordable single-family homes in the United States, and certainly not in Montana. So, the constraints that were placed by zoning made it almost impossible. Luckily, we came up with a solution so that eight Acres of a site are now going to be devoted to affordable, that is for middle-income sort of city workers. So those kinds of trade-offs are important.

I should also add that this issue of green gentrification: there’s a concept of make it “just green enough”. That is make a just green enough that the wealthy people won’t want it, but it’s okay for the poor people. I defy that concept because in all of my work and central Brooklyn, in the South Bronx, and Harlem, I never had a community member say to me “make it just green enough don’t make it as nice as Central Park”. I heard just the opposite: make it as nice as the parks in the rich neighborhoods. And that’s the debate. That’s the problem. T he poor people who live there don’t want a second-class park. They want a first-class park. But if you build the first-class Park, will the poor people be displaced? That’s the big problem. So it’s it is a dilemma.

David: Let’s take a couple of questions from the audience.

Audience member: Hi. I’m wondering if the green gentrification is like a bubble that might just burst in the similar way. We talk about housing in Australia. Is it just a matter of time until the bubble bursts and we have it everywhere. And in the meantime, do we just have to bear the pain?

Isabelle: The problem with housing bubbles is that they burst and then we grow again because we don’t learn and we don’t question our models of growth and development. So hopefully it will burst but I think—and it’s tragic at the same time to think about it this way—as the middle class becomes increasingly impacted by having to leave and then cities lose a variety of their workforce, then they will really starting start questioning what type of housing they need to provide and how to fund it better. So, in the end of the day. it will also become much bigger housing agenda. There are a lot of housing platforms growing in many countries because housing has become an emergency.

Audience member: It’s not really a question; it is more comment or a proposal. I’m thinking about this concept of resilience that we are all are very familiar with. We can have an ecosystem that is resilient but not necessarily just. So we can use a social-ecological approach or social ecological systems approach. Okay, that’s good. I can bring local knowledge. I can network social capital of the people there. and I can use their knowledge to better manage the ecosystem. But still, the definition comes up short when it comes to environmental justice. So, I don’t know if we should keep on relying on this concept. I don’t know if it is an outcome from this conference. Why not create a new definition of resilience, in support of those ecosystems that can support and maintain ecological processes, but also are based on on justice for everyone?

Adrian: I spent some time this morning with the local Parisian parks officials, and they have some really sophisticated metrics now. They’re built into how they design new parks. And, of course, space is at a premium in Paris, and they are trying to put a whole lot into small spaces. What they said to me was that the smallest spaces are the more difficult, because they have to address all of these different demands—the equity demands, the resilience demands—and it was remarkable to see how much you’re squeezing into a six hectare park, roughly 14 acres, where they’re putting in humid zones and native plantings and play areas and all these things,

They created a program, a computer program, that the community could tap into called Design Your Own Park. You can put in all the elements you want, and then the program reports the price, and you have to figure out which you can’t afford to do. It shows an increasing sophistication, with resilience being at the top of what they were looking for and also social aspects being done for this park. I worry that we’re expecting a park to play too many roles, expecting that this park is going to solve all our problems, make us resilient, do all these things. At the end of the day, i’s got to be a great park that brings people together.

As I’ve traveled around Paris, seeing these tiny little parks with a lot of different things in them, and really being used … this is the greatest value of parks. It is not the health benefit or the environmental benefits. It’s people interacting with people which makes a great City and when you leave and you go to the suburbs in your in your private home and you don’t have parks and you have a backyard, it’s not people interacting with people. That’s the greatest virtue of parks. In my four decades of working in parks, it is the connection between people which defines what makes cities not just great, but also viable .

Samarth: So just to talk about the issue of ecology and open spaces. The movement of public space in Mumbai is very intensely interlinked with the movement to reclaim our natural assets and our ecological corridors, because in Mumbai we are faced with another problem. It’s interesting that all three presentations started off with mapping as an exercise—mapping as a means to empower a certain pocket of land, a park, a certain group of people. So, mapping is a tool to the to enable the Right to the City in Mumbai.

What’s interesting is that the mapping we did wasn’t just limited to the open spaces, but it also mapped the mangroves, the forests, the creeks, the salt pan lands, the wetlands. These areas had never existed on the map of Mumbai. In fact, after we did this mapping the city has recognized these resources for the first time in the last 60 years. The new development plan of the city actually has areas marked with edges with buffer zones for mangroves to wetlands to salt pan lands. Now there is a legitimate means to fight for them. So, for communities like us, activists who are looking to fight legal battles, these maps become legal tools.

We had a Seed Session yesterday about the Right to the City, which was very exciting. I believe access to open spaces, and at the same time access to natural spaces, which ensure vigilance and ensure their protection equally, stake a claim in the Right to the City,

David: Please thank our panel

about the writer

Isabelle Michele Sophie Anguelovski

Isabelle Anguelovski is a Senior Researcher at the Institute for Environmental Science and Technology at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. She is a social scientist trained in urban and environmental planning and coordinator of the research line Cities and Environmental Justice.

about the writer

Adrian Benepe

Adrian Benepe has worked for more than 30 years protecting and enhancing parks, gardens and historic resources, most recently as the Commissioner of Parks & Recreation in New York City, and now on a national level as Senior Vice President for City Park Development for the Trust for Public Land.

about the writer

Samarth Das

Samarth Das is an Urban Designer and Architect based in Mumbai. Having practiced professionally in Ahmedabad, Mumbai, and subsequently in New York City, his work focuses on engaging actively in both public as well as private sectors—to design articulate shared spaces within cities that promote participation and interaction amongst people.

about the writer

Isabelle Michele Sophie Anguelovski

Isabelle Anguelovski is a Senior Researcher at the Institute for Environmental Science and Technology at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. She is a social scientist trained in urban and environmental planning and coordinator of the research line Cities and Environmental Justice.

Isabelle Anguelovski

This question is particularly important because traditionally, lower-income and minority residents suffer to a greater extent from environmental toxics, climate risks, and poor access to green space/infrastructure in comparison with white and higher-income residents.

These inequalities are illustrated by earlier highway construction projects replacing valuable green space for people of color, such as the I-10 construction on Clairborne Avenue in New Orleans in the 1960s, and by more recent unequal access to green space for Latino and Black residents in places like Los Angeles County. Such inequities have a particularly strong health ramification since high exposure to green space is associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality. Put differently, unequal access to green space by race, ethnicity, or class also shapes health inequalities and disparities.

Unequal access to green amenities more generally have been produced by urban development trends, including what is now increasingly known as green gentrification. In the context of cities advancing green agendas, visions, and urbanism, our research on green gentrification trens shows that green amenities can create conditions for the social and spatial exclusion of the most socially and racially vulnerable residents, their livelihoods, and practices. Parks, greenways, or climate-proofing infrastructure can become GREENLULUS in racially mixed and low-income neighborhoods.

In our Barcelona Lab for Urban Environmental Justice and Sustainability (BCNUEJ), our research has shown city-wide green gentrification trends in places like Barcelona, where approximately half of the new green spaces created between 1990 and 2005 contributed to strong green gentrification. We have seen similar trends in our recent study of Washington DC, where green space creation predicted losses in African-American residents. In addition, in DC, we were able to pinpoint that the green spaces most associated with green gentrification seem to be community gardens, which have historically been spaces of refuge for people of color. Finally, our latest study, in Boston, confirms the association between community gardens and gentrification, while also adding greenways to the picture of green gentrification. Greenways are particularly important because of the emphasis of local climate plans, such as the 2018 Boston Harbor Plan, on linear resilient parks to address stormwater and flooding.

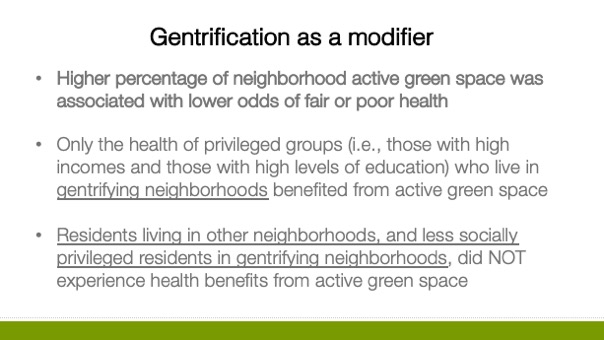

Bringing it back to health, our work also tries to understand whether everyone’s health benefits from green space and other livability initiatives or, alternatively, whether the process of green gentrification cause worse health outcomes for some and better health outcomes for others. In a recent study of NYC, being exposed as a resident to a higher percentage of neighborhood active green space was associated with lower odds of fair or poor health. We also found that only the health of privileged groups (i.e., those with high incomes and those with high levels of education) who live in gentrifying neighborhoods benefited from active green space. In contrast, residents living in other neighborhoods, and less socially privileged residents in gentrifying neighborhoods, did not experience health benefits from active green space.

Knowing this reality, what are counter-examples of green, inclusive, equitable planning? One example that comes to mind is the Superblock program in Barcelona. Embedded in the 2012 urban mobility plan, this program combines climate mitigation (emission reduction) and adaptation (heat island) goals. By altering mobility and enhancing access to public/open spaces, it proposes new a urban development path and city vision questioning spatial growth. Additionally, by planning to build more than 500 superblocks in the city, the plan emphasizes an equality-driven vision where all neighborhoods in the city would benefit from superblocks. In our views, this approach may avoid a “flagship” effect, whereby some projects draw specific attention, investment, and possibly green speculation. The HighLine example in New York is a prime example of this process.

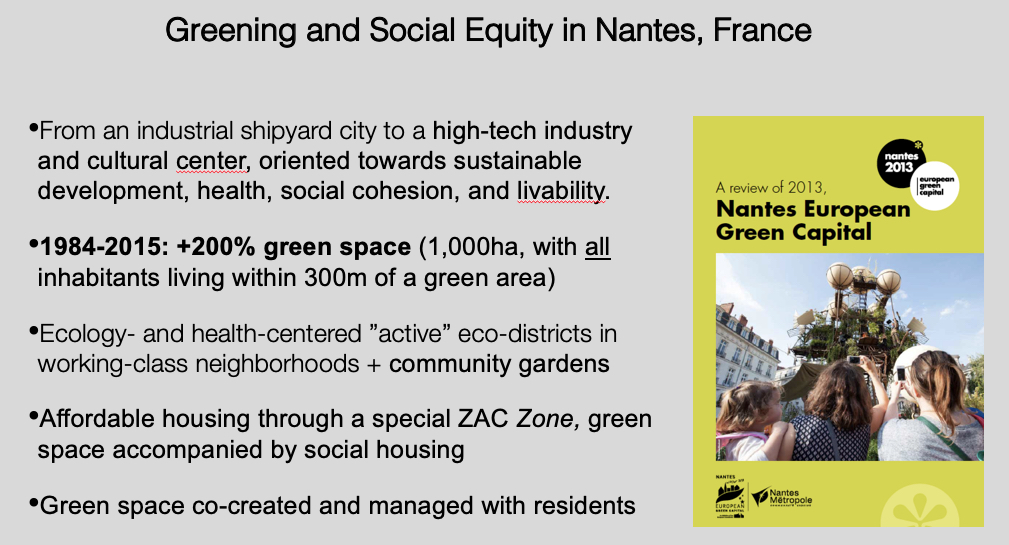

Another socially-inclusive greening approach was adopted by Nantes in France at the beginning of the 1990s. At that time, Nantes decided to operate a transition from an industrial shipyard city to a high-tech industry and cultural center, oriented towards sustainable development, health, social cohesion, and livability. From 1984 to 2015, it added 200% green space (1,000ha), and achieved its stated goal of allowing all inhabitants to live within 300m of a green area. During this greening process, Nantes also created ecology- and health-centered ”active” eco-districts in working-class neighborhoods. Last, it added different affordable housing schemes and projects in redeveloped green neighborhoods. One of the most strongest regulations here is the obligation for developers to include 30% of affordable units for every new development. Last, this greening trajectory has been operated in an inclusive manner: In Nantes, green space is co-created and managed with residents, with large resources and times allocated to the Green Space Department to developing new uses, programming, and activities in green spaces.

In sum, urban greening and green spaces are vital to ecological and human health. However, we in our BCNUEJ lab, we argue that achieving equity in urban health and reducing health inequalities requires a more complex approach than simply claiming that urban greening contributes to better health or livability.

In sum, urban greening and green spaces are vital to ecological and human health. However, we in our BCNUEJ lab, we argue that achieving equity in urban health and reducing health inequalities requires a more complex approach than simply claiming that urban greening contributes to better health or livability.

In closure, I would like to propose a few directions for planning green and equitable cities: In our views, cities should integrate the concerns and local uses of social groups that might be less vocal or visible is core to the process of designing equitably beneficial public/green space. They should direct public action in ways that places the well-being and health of existing residents at the center of public policy and planning, and that controls real estate development, housing rights, and mass tourism. Policy-makers should also consider how supra-local constraints and politics undermine sustainability planning and decisions and build lasting wider socio-ecological political coalitions. Finally, there should be greater genuine cooperation between public entities and institutions at different territorial levels so that equitable greening is not envisioned and achieved at the municipal scale only, but takes metropolitan and regional realities into consideration as well.

about the writer

Adrian Benepe

Adrian Benepe has worked for more than 30 years protecting and enhancing parks, gardens and historic resources, most recently as the Commissioner of Parks & Recreation in New York City, and now on a national level as Senior Vice President for City Park Development for the Trust for Public Land.

Adrian Benepe

The right to green space is a new idea, necessitated by the swelling populations of high-density urban areas, and the need to provide respite, relief, and leisure for those communities who are often on the frontlines of the worsening impacts of climate change. Excessive heat, flooding from storm water runoff and rising seas, deteriorating air quality, and the ensuing health challenges exacerbated by these factors, all require a reimagining of the physical and social infrastructure that compose our cities. Part of that is a new way of thinking about green space, and proclaiming it as a right as opposed to an amenity.

As we demand and proclaim the right to parks and open space, we can ground the abstract in the tangible by introducing a metric for park access: the 10-minute walk. The Trust for Public Land (TPL) has adopted a 10-minute walk (half a mile—or roughly 800 meters) to a park as our principle metric in assessing park access in cities across the United States, and we have launched a campaign—The 10 Minute Walk Mayors Campaign—to sign up mayors (300 and counting) willing to make a commitment to 100 percent 10-minute walk park access in their cities by 2050: the “100% Promise”.

TPL has also helped create or transform more than 500 parks that give 8 million people access to a high quality park within a short walk. One of our programs, NYC Playgrounds, has transformed over 200 asphalt schoolyards in New York City into thriving, green community playgrounds. The model created by this program has been adopted by cities across the US, and we have added more green schoolyard programs in cities like Philadelphia, Camden, Dallas, Atlanta, and Oakland. Paris, our host city for The Nature of Cities’ Summit, has very successfully incorporated the green schoolyard model into their sustainability plans, and have already transformed a number of sites through their Urban Oasis project, thanks to the “importing” of the TPL model by Bloomberg Associates. It’s a model that offers perhaps the best way for creating park access at scale, since most neighborhoods have schools, and by recreating their adjacent schoolyards into public playgrounds, we can create new green space without having to actually acquire new land—a difficult and very expensive prospect. It of course has its own complexities, like the need for a joint-use agreement between municipal agencies, but it nonetheless has the potential to deliver 10-minute walk park access to tens of millions of people.

As we ask mayors to make specific commitments, we are also equipping the public and city officials with the data necessary for spurring action and guiding implementation. Two TPL resources, ParkServe and ParkScore, do just this. In creating ParkServe, we mapped 14,000 communities in the United States to locate 131,000 parks and identify gaps in park access, and to find out how many residents did not have a park within a 10-minute walk. We also built in a tool where park planners locate optimal points for new parks that would provide the most people the most benefits, and layered these maps with information about the demographics of communities, using census data. We then fed all this information into ParkScore, which ranks the 100 top park systems in the countries according to access, amenities, funding, and a host of other criteria. This year, Washington D.C. came out on top, beating out the prior champion St. Paul, Minnesota, by a narrow margin. ParkScore is a potent tool, as mayors are naturally competitive. By ranking cities, we’ve found that mayors have been incentivized to improve their park systems, creating a race to the top. As a validation of our efforts to elevate the role of parks in the public discourse, the most recent US Conference of Mayors survey listed parks and open space as the number one sub-issue for mayors in 2019.

With many mayors now on board, and the right to green space gaining traction, we are now working with cities to help them meet their commitments and reach the goals they have set for themselves. All of us—community groups, constituents, and non-profits—must continue to celebrate visionary leaders and help them succeed, so that the right to green space is asserted and made a fundamental human right for city dwellers in perpetuity.

With many mayors now on board, and the right to green space gaining traction, we are now working with cities to help them meet their commitments and reach the goals they have set for themselves. All of us—community groups, constituents, and non-profits—must continue to celebrate visionary leaders and help them succeed, so that the right to green space is asserted and made a fundamental human right for city dwellers in perpetuity.

With additional writing and research by Thomas Newman, National Programs Coordinator, The Trust for Public Land

about the writer

Samarth Das

Samarth Das is an Urban Designer and Architect based in Mumbai. Having practiced professionally in Ahmedabad, Mumbai, and subsequently in New York City, his work focuses on engaging actively in both public as well as private sectors—to design articulate shared spaces within cities that promote participation and interaction amongst people.

Samarth Das

We are currently seeing a rising trend of ‘gated communities’ crop up all throughout the city of Mumbai. These gated communities further the fragmentation and segregation of the city’s fabric; as well as re-inforce and re-assert the several social and economic divides between various classes of people that call the city their home. By the sheer nature of their planning and construction, they promote an ‘exclusiveness’ and thereby a certain apathy towards the surroundings they are located in. Romantic ideas of a utopic lifestyle complete with private parks and amenities are sold to buyers in the market – boldly acknowledging that one needs to ‘get away’ from the disrepair and hopelessness of the city itself in order to find comfort and feel ‘at home’.

The isolation that these types of developments promote stands equally true to the built as well as un-built environments. The concept of ‘nature’ is becoming increasingly manicured – almost manufactured – with little or very less importance given to natural eco-systems and environments.

Photo: Johnny Miller, Unequal Scenes, Mumbai

It is important, in this scenario, to build and define relationships collectively between people as well as with nature especially on questions of integration, cohesiveness, co-habitation and sustainability. Over the last 40 years, our architectural endeavours and our design practice PK Das & Associates, have stood by the belief that organising movements and creating grassroots networks would certainly help in defining these relationships.

Wider public dialogue and popularisation of ideas are necessary means towards the achievement of political recognition and thereby influencing structural legislative changes. The practice has been fairly successful in achieving these goals through city-wide public exhibitions for example, which have seen participation from key government officials and politicians; as well as organising and participating in public marches and protests with communities around issues of protecting their neighbourhood parks, gardens and open spaces.

Need for collective intervention

In 2007, we launched the Juhu Vision Plan—which propagated the idea of neighbourhood based planning for cities, instead of ‘city wide’ master plans—which are often alienating to many. Juhu is a western suburb of Mumbai, and this project envisions a public realm integrated into the neighbourhood through networking the public spaces and natural assets in the area. Providing access to these areas also ensures vigilance and protection. We evolved campaign posters in order to sensitise the community about the project as well as achieve the larger goal of popularising planning. The press and media become an indispensable part of this process by helping increase awareness amongst citizens, and ensuring accountability on behalf of governments.

Integrating the backyards

Focussing on eliminating the expanding backyards of filth, abuse, discrimination and exclusion of places as well as people is a priority as it is undermining urbanisation and the very idea of cities. We argue that ‘urban’ is a larger concept that lends to a certain quality of life and spaces that respect our built as well as natural environments. Therefore, not all cities are ‘urban’; rather in this context rural areas and villages can be far more progressive than cities and thereby are more ‘urban’ in nature.

‘Nullahs’ were originally planned as open water channels – following natural low lying areas and drain channels in order to take storm water from the land to the sea. Unfortunately the apathy with which natural assets are dealt with have turned these potentially incredible waterways into open sewers and dumping grounds carrying the filth of untreated sewage to the sea. It is indeed a challenge to engage with the invisible yet perceived barriers across city landscapes while ensuring their unification.

Through urban planning and design endeavours

Urban planning and design are effective democratic tools of social and environmental change and such change must be demonstrative through participatory means and wider collective action, as has been in the cases of several neighbourhoods of Mumbai.

Irla Nullah

The movement to reclaim our neglected backyards has since moved on to several other projects. One of the most significant of these is the restoration of the Irla Nullah. In the process of re-appropriating these spaces, the project has been successful in creating walking and cycling tracks complete with landscaping and lighting and performance spaces which ensure that these spaces are multi-functional yet open to be appropriated in any way as deemed fit by the community.

Owing to its physical footprint, this “nullah” weaves through various neighbourhoods. What better way to connect and integrate our various disparate communities within cities than to develop a string of linear parks and shared spaces along such watercourses —which provides easy access from every neighbourhood adjacent to them? The idea is to advocate smaller, pocket and linear parks that are within walking distance instead of major, city level central parks which we all have to travel to using some means of transport. This project is also the first of its kind in the country where there is an attempt to clean the waters flowing in these nullahs. With over 150kms of ‘nullahs’ running across the city of Mumbai, the potential of this project’s scalability is enormous.

Bring about citywide transformative change

Bottom up processes and their scalability to city-wide transformative change must be a necessary mission in the re-envisioning of cities and their sustainability. The movement to reclaim public spaces in Mumbai started almost 23 years ago. Through all our public work and engagements we have engaged with communities in each neighbourhood. With every project our understanding of the city grows, and with it, the potential for scalability of ideas across these various projects increases.

Movement to reclaim public spaces in Mumbai – 23 years and continuing

Image credit: PK Das & Associates

Open Mumbai

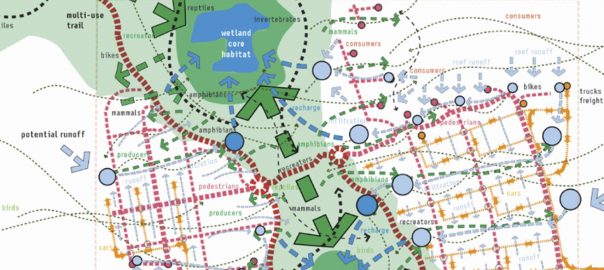

In 2012, we held an elaborate city-wide exhibition called ‘Open Mumbai: Re-envisioning the city and its open spaces’ . A mapping of open and natural spaces in the city revealed some incredible facts. A brief list of the incredible natural assets that we fail to realise within our city can be seen in the image below. Sadly, we have failed to recognise in our city’s development plans. This ignited the idea for the Open Mumbai Plan. vThe Open Mumbai plan proposes the re-invigoration and re-integration of over 300 kms of the natural watercourses within our city’s landscape; and thereby develop a network of linear parks and shared spaces across neighbourhoods and the city.

A plan that aims to create non-barricaded, non-exclusive, non-elitist spaces that provide access to all our citizens. A plan that ensures that open space is not just available, but is geographically and culturally integral to neighbourhoods and a participatory community life. A plan that we hope will be the beginning of a dialogue to create a truly representative “People’s Plan’ for the city of Mumbai”.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation