Introduction

about the writer

Samarth Das

Samarth Das is an Urban Designer and Architect based in Mumbai. Having practiced professionally in Ahmedabad, Mumbai, and subsequently in New York City, his work focuses on engaging actively in both public as well as private sectors—to design articulate shared spaces within cities that promote participation and interaction amongst people.

about the writer

Elisa Silva

Elisa Silva is director and founder of Enlace Arquitectura 2007 and Enlace Foundation 2017, established in Caracas, Venezuela. Projects focus on raising awareness of spatial inequality and the urban environment through public space, the integration of informal settlements and community engagement in rural landscapes.

about the writer

David Simon

David Simon is Professor of Development Geography at Royal Holloway, University of London and until December 2019 was also Director of Mistra Urban Futures, an international research centre on sustainable cities based at Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden.

about the writer

Xin Yu

Xin Yu (aka Fish) is Shenzhen Conservation Director and Youth Engagement Director of The Nature Conservancy China Program. Since 2017, he has overseen TNC’s first City project in Shenzhen, China, focusing on Sponge City

How can we create living space in cities? This was the theme of one of the Dialogues at The Nature of Cities Summit in Paris, with architect Elisa Silva (Caracas), social scientist David Simon (London), and urbanist and non-profit campaigner Xin (aka Fish) Yu (Shenzhen), and moderated by architect Samarth Das (Mumbai). Public spaces within cities commonly take on various forms: squares, parks, sidewalks, and even rooftops in dense conditions. How can we build space in the public realm that creates accessible areas that are both alive and for living? What makes them “work”? How are they negotiated among stakeholders?

There were two common themes among the three diverse responses. One is the key idea of shared space, both in terms of use, but also creation. When we build cities, we need to consider not just not public space, narrowly conceived, but shared space that may take many forms and emerge from various sources. Shared spaces must facilitate uses by and interactions among all types of users. We might seek out new uses for familiar spaces—a parking lot to a playground, for example, a shared rooftop to a garden.

A second theme is the idea that engagement among stakeholders—residents, government, business, civil society—is a critical part of every successful shared space. This process of engagement builds on shared experience. It contributes to overall improvement of the project itself, and most importantly ensures that it thrives on people’s emotional connection to the space upon completion. Engagement cultivates broader acceptance of modified land uses, but also curate new ideas about how land could and should be used.

At the TNOC Summit, we largely avoided long presentations in plenary—i.e. “Keynotes”. Rather, even when we gathered in our largest group, we met for “Dialogues”, similar to the Roundtable format at TNOC. For each dialogue there was a core question or prompt, such as the one in this Roundtable. We invited three people to participate, striving for a multi-disciplinary group, with diverse points of view, perspectives, and approaches. Each of the three delivered a short intervention (about 8 minutes), and then sat together for a longer conversation. We are publishing all of the Summit dialogues in oder to make the ideas widely available and keep the conversations going beyond the Summit itself.

In this Roundtable, we present both their written texts (essentially a transcription of their presentations) and video of their presentations. Also you can find a transcription and video of the conversation below.

https://vimeo.com/388255518

A transcription of the conversation

Samarth Das (moderator): Thank you all for very exciting set of presentations and thoughts. Before we jump into the first question, I want to string through all three of your dialogues. The one common theme that definitely comes out is the idea of shared space. I think it builds on the earlier discussion we had this morning about shared urban squares—it’s not public it’s shared. And the idea that engagement is a key asset is a key part of each of those discussions, so building on the shared experience. David (Simon), I’d like to take you up on the idea of the living and the livable, you know something that we had discussed. So how do we develop Living Spaces that are at the same time accessible to make them livable? Spaces in that sense. There’s always a tension between experts and locals and their thoughts about this. So, what are your thoughts?

David Simon: Well that comes back to my point about bringing together the different stakeholders living in a particular existing urban area or who are the intended residents of a new area in the process of being developed. The crucial thing about livability is both the physical environment meeting the needs both in a material sense, but also, as I said in my introductory comments in terms of social and cultural values. One can highlight this for example, in terms of the difference: If you look at indigenous cultures in different parts of the world, the way in which space is used socially is often very different. In some cultures and societies traditionally there were spaces for men and women to use together. There are spaces reserved for women and for men both domestically within the domestic sphere but even in public space and these are kind of superimposed layers.

In the conventional modern—as in driven by town planning since the late 19th century in a very sort of Western technocratic sense—the division between public and private is seem as a simple binary division. There’s something called public which belongs to one or other of the public governmental bodies and there’s something called private which belongs to individual people, individual households, individual firms, or other entities. So, in many societies, it’s much more complex and, without necessarily passing a value judgment about whether this is good or bad, the point is simply that if you going to have livable space it has to be culturally appropriate for the people and the values who are going to inhabit them. Otherwise, it becomes part of the challenge of alienation, of dysfunctional space, of anomie, and then we find that all sorts of other social problems relating to unemployment, individual alienation, substance abuse, violence of different sorts become much more prominent and that’s why some of the initiatives that Elisa Illustrated working with children, with youth, with other groups, and getting them to understand and to use and to make the spaces that already exist more expressive of themselves is a crucial part of all of those livability strategies.

Samarth Das: So Elisa, building on what David just said, you did demonstrate how children have been included in the process, the young adults. Tell us a little bit about how that promotes the building of a better Community.

Elisa Silva: These communities where I work and the country in general is very polarized politically. Very much so, and that’s something that is a challenge to work with. Children end up being an amazing tool to overcome that and by engaging them in these conversations and in the end somehow, it’s been a first sort of way to enter. They are as a community very aware that children don’t have safe spaces for play, places for them to really claim as their own, so because of all the obstacles and the difficulties and resources etcetera, we found that that was a way that made it easier to enter into this conversation with the communities and their enthusiasm of children. Because what we quickly picked up on is that we needed to make this fun, as Fish was saying, so every activity we’re doing with them was already somehow occupying and using that public space or that future public space that hadn’t yet been intervened by them or through the design process with them, but that they could already envision it as being something different. And then because they of their low resistance and willingness to play, it created a buy-in from the rest of the community, the adults who might have been more skeptical and those who don’t speak to each other because they’re on different sides of the political fence.

Samarth Das: So essentially it’s about building trust in within communities. So Fish, through your very specific example, how did that project really help build that trust that really opens up many avenues?

Fish Yu: Yeah. That was difficult. In the most of the preparing time we were kind of worrying about if this can be done in that special area, because that’s where Governments try not to really put lots of research resources in there. And so we try to do something but without any available regulation and so the people come to ask for permission, if you are allowed to do such project there, we didn’t know, we didn’t have that, and nobody has that. There is no current procedure of applying for such a permit. So, we were spending lots of time working on that and we try to involve the local residents to talk about the project and to talk about their needs and what do they want in the future for the space?

But there is particularly difficult to conduct in China since we have a very limited sense of community. So you’re you’re not really able to find those people, where those people are in the community. It’s really challenging. Eventually, we talked some of those representatives from the Iresidents, from one building alone, but we failed to find so many from the buildings around them. So, I think the trust building is a gradual growing process. You might not be able to do, at the very first place, for the entire whole process, but we found happiness that we keep learning. We still keep this experience getting more and more for the future development. So, we would like to share those local groups in the city and we try to engage more civil organizations to join us to build this part of trust-building process.

Samarth Dad 1: You mentioned these processes take time. And then you also showed us a slide where in a matter of years landscape is completely transformed into something absolutely unrecognizable. And you know Elisa, we have time as a factor of scale that we talk about. You have different processes that have their own timelines and yet they all need to come together to somehow contribute towards that larger process. That must be challenging to deal with if not the most challenging aspect but one of the most challenging aspects about this. What are your thoughts about dealing with time and managing timelines for these kinds of processes?

Elisa Silva: Well difficult and indeed challenging what we’re doing and in both of the examples that I showed in the case of Venezuela I think it’s a situation where it’s pretty much impossible to get all of the different actors that you would need involved, especially government and local government. So, there’s a little bit of faith that somehow we might be leading the time in this process and also as a way of resistance against or resistance towards survival. Resistance of a desire to continue to create livable situations, even though we’re very much going against the current. So in that sense, I think it’s a sort of an obstinate way of resistance. The one that has to do with so many other systems and landscapes. It is a challenge. I think most important is to map it, and show it, and make it visible, which has not really been done very clearly, neither for the stakeholders nor for the community itself.

Samarth Das: All right before we just move on to a few questions from the crowd, David that aspect of time relates very directly to some of the challenges that you face in co-production and co-creation. I like that you use those words. It’s recurring again with a theme of shared spaces. So how are those tackled?

David Simon: Well, I think it’s exactly as Fish just said, a case of building trust and confidence which is slow, it’s step by step, and it’s also very easy to break or to lose trust and confidence very quickly. So it’s an asymmetrical process and that’s why one has to be so careful that you don’t have a cross cutting or a contradictory intervention from one other stakeholder that undermines the whole process. But I also, just in the broader context of what we’re discussing, want to draw attention to the fact that there is also a challenge between the permanence, at least in terms of a number of decades, of the urban fabric as we design and build it out of these permanent materials of steel concrete glass metal wood, whatever, and the rapidity and the speed of technological change of demographic and social change, which means that today’s reality is often trying to figure out how to live in inflexible spaces, but where the needs have become very different.

So one example is how in the space of a few decades in many societies—and that number is fewer in the rapidly urbanizing parts of the world–we’ve moved from a situation where extended families are the social norm. However, they are constructed in different cultural contexts to a situation where the nuclear family of two parents and two children or whatever was regarded as the norm to a situation today where in most of the major cities in western Europe and North America between 1/4 and 1/3 of households comprise one adult often living alone, single person households. So, if one thinks about the challenges and those of course are at different stages of the life stage could be separation divorce never partnered—but increasingly it’s the elderly who have lost their life partner in one sense or another—so there is a huge challenge of making today’s urban fabric in the temperate zones, if you like of the world appropriate to the needs of single-person households of different demographic ages and stages.

Samarth Das: Localized approaches, right? That’s basically what it is. All right. Do we have any questions?

Audience member: I’m used to Mediterranean hilltop towns and I figure they probably grew up like the barios. So I’m wondering you know, is there a chance that today’s barrios will become the desirable places to live of the future?

Audience member: Hi, very very interesting session. And I’m glad that David Simon asked or mentioned about different demographics and different kind of households. I just wanted to go through give me a couple of minutes a couple of thoughts where you spoke about private and public spaces and then move say compound idea of private semi-private and public which is what courtyards or corridors outside of houses are considered and then moving into the modern society where you actually can have pockets of private in public spaces and pockets of public on your phone in very very private spaces. So what I just wanted to highlight is that in each of these contexts I think safety is one aspect which was spoken about by the group, but then also maybe legitimacy of doing what we can can do in different kinds of spaces and transparency as well as viewership. So how much of what you do in a private space is actually visible to the outside and how much that you can do in a public space is actually not visible to the public around you and especially because I have lived in three cities in the global South Delhic Cape Town and Bangalore. My one question is often our solutions are for the communities which seem to not have public space to call their own and nature is called upon to bring people together, especially the youth. There is also in a city such as Cape Town where apartheid is well not rife, but there are consequences of it that are still there in the urban fabric and you have families which are and households which actually are completely isolated from each other. Sorry. I’m going on too long, but I just wanted to know if there are examples of people here working with non-vulnerable social groups to bring them in a more public open space. Thanks.

Elisa Silva: Regarding the first question, I’ve thought about that a lot. Yes, I think barrios are a medieval village basically just built in the 20th century. And even though our approach has been very much thinking that public space can be a way to integrate them, I’m very keen right now actually on resignifying existing spaces as their as they are in their public dimension, or their common dimension, or their shared dimension, to recognize the values of those kinds of spaces, which organically were constructed by the people and represented them somehow to the rest of the city in a different light, so that they might find them as valuable as they in fact are. And another kind of really interesting thing that I would like to be able to learn from comparing medieval towns and how they grew for example, the gothic Barrio Barcelona and its expansion is just exactly in that moment where you go from a transition of a planned, gridded area and a medieval fabric—in Barcelona there different, but you just reverse them without ever feeling like you’re going through some gigantic threshold, which is not the case. In Barrios such as Caracas people have in their mind that they’re going into some other world and that’s really where I think there’s an opportunity there to be more specific, to be more mindful of what that can mean. I was in Amalfi on the coast and just in this amazing setting with Gucci stores and Chanel and I realized this boulevard is a creek. I’m certain that it’s a creek and as I walked up to the very end, of course, it had been covered and now it’s clean water that comes out into the ocean. But that’s essentially how barrios have emerged in the fabric of Caracas. They often occupied creeks. And so to be able to imagine that that same transformation would happen seems very logical.

David Simon: Let me pick up the question about different categories of public space and semi-private and private and how you identify them. This was a profound challenge that we faced during the campaign to create the urban sustainable development goal, which is now goalie 11. Where as you probably know there is a target and there are indicators about the extent of public space and the challenge was very simply that it was almost impossible to find an indicator that would work in all countries and all urban contexts because—precisely the point you made—that how open space, and that’s why it’s eventually defined as open space, is controlled very so much between local authorities different categories of private entity, regional, states institutions, and the national state as well as all the other planning issues… so it became impossible to find a sort of single indicator of public open space.

So, the definition shifted towards the open, and even there we’ve had to rely increasingly on remote sensing and other techniques that need ground-truthing to test the accessibility because there are different gatekeeping rules regulations fences boundaries financial disincentives and all the rest.

Samarth Das: Any last thoughts from you Fish before we close?

Fish Yu: I’ll probably just share a little story how we managed to communicate about this specific project. And once we found people having trouble with understanding this idea, then we actually put stuff over the window to stop try to stop the construction. We found a way, we actually put up of plants to show them what’s going on there, that they see the color change. They see there’s something else going on with the nature of the environment. So, they stop doing that. They start smiling with us. So that’s just the real change we sensed that then we can do practically to change people’s idea. I think that’s something to think about. Maybe we can find different ways of communication, different manners to make people understand what’s going on with urban environment

Samarth Das: So, lots of takeaways for what makes public spaces and shared spaces work. Thank you all for joining us here this morning, and thank you to the audience. Thank you.

Fish Yu

about the writer

Xin Yu

Xin Yu (aka Fish) is Shenzhen Conservation Director and Youth Engagement Director of The Nature Conservancy China Program. Since 2017, he has overseen TNC’s first City project in Shenzhen, China, focusing on Sponge City

On the opening day of our rooftop community space, we invited politicians, media, designers, and experts from different sectors to bear witness. We found this place has become more than just a Living Space of Nature, but a real living space to we try to talk about the ideas of today—a cultural hotspot.

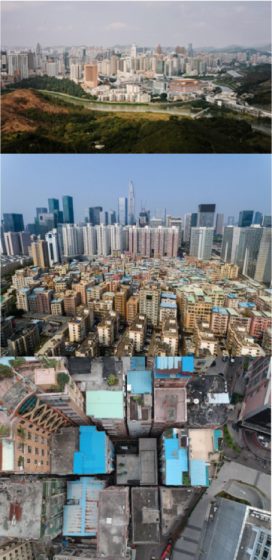

Wow, that’s big crowd. Thank you. Well, I’m not surprised if you have ever heard of name of Shenzhen since the city’s so young. This is a photo taken 40 years ago from the New Territory of Hong Kong to those who know. You can see in just 35 years there is a big change took place in that area. Now we have this city with a population around 20 million.

Wow, that’s big crowd. Thank you. Well, I’m not surprised if you have ever heard of name of Shenzhen since the city’s so young. This is a photo taken 40 years ago from the New Territory of Hong Kong to those who know. You can see in just 35 years there is a big change took place in that area. Now we have this city with a population around 20 million.

You might be surprised that I’m telling you half of the city’s population now living in the area we call Urban Village. Take a close look. You can sense the density and the distance between those buildings. This is a main street in this urban village of Gangxia. You can tell the living condition there looks convenient. Residents can find pretty much everything from stores, restaurants to mini Banks…

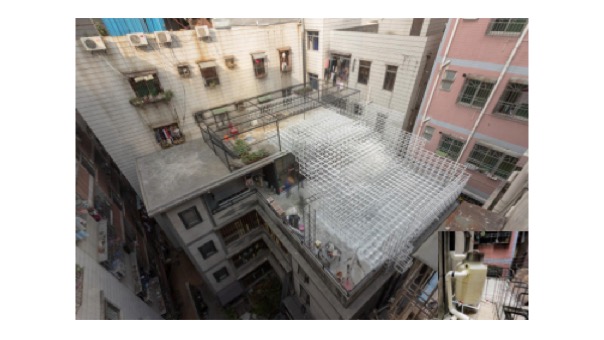

But when you look up, the sky becomes narrow and you can feel the pressure from this built environment and people from Village. People can gather in very little options of space in those urban village areas to have fun and even find a job. This is where we start our project where is on a kind of unique building roof in this area.

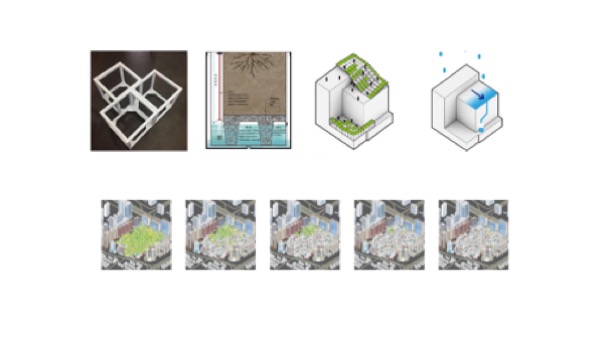

It is one of the oldest buildings in the village and it is smaller than the normal size in the area. We try to use the simplest structure and to make it capable to hold as much water as possible. A 65% of run-off control rate is in this case. The green color on the screen is representing the plants. We also have a name for this project called Green Cloud for people to understand what’s going on in the future days possibly starting from this little building.

It is one of the oldest buildings in the village and it is smaller than the normal size in the area. We try to use the simplest structure and to make it capable to hold as much water as possible. A 65% of run-off control rate is in this case. The green color on the screen is representing the plants. We also have a name for this project called Green Cloud for people to understand what’s going on in the future days possibly starting from this little building.

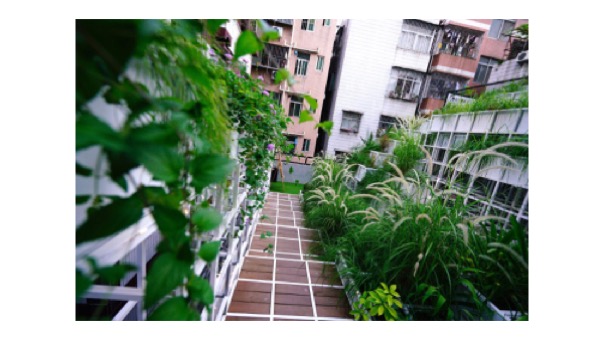

With this steel structure and rain bucket, we made this place become looking like this, from different angles, and with those local species you choose. This was taken in its three months’ time. It really became a very green and functional place.

With this steel structure and rain bucket, we made this place become looking like this, from different angles, and with those local species you choose. This was taken in its three months’ time. It really became a very green and functional place.

But there are also stories about people. In the very first two weeks, people living around this building gave lots of complaints because they thought that we were trying to build another floor of the building and local executors came to stop us. We did a lot of communication with the local authorities to let them understand what’s going on. Finally, they gave us a green light. And then we try to engage as many participants as possible from universities and also from it residents. Young people come together to help some of the construction work.

On the opening day, we invited politicians, media, designers, and experts from different sectors of the city to bear the witness. And later on we found this place has become more than just a Living Space of Nature, but a real living space to we try to talk about today. It becomes a cultural hotspot for people to do different types of activities over there. We invited student volunteers to come to have a classical music concert for people living there who rarely have a chance to go to the Music Hall and more importantly we find this distance between those buildings become an advantage for people to be able to stand in front of the window to listen to the music and eventually this area turns out to be now a nature education classroom for the kids in the village to come and learn some science and nature.

On the opening day, we invited politicians, media, designers, and experts from different sectors of the city to bear the witness. And later on we found this place has become more than just a Living Space of Nature, but a real living space to we try to talk about today. It becomes a cultural hotspot for people to do different types of activities over there. We invited student volunteers to come to have a classical music concert for people living there who rarely have a chance to go to the Music Hall and more importantly we find this distance between those buildings become an advantage for people to be able to stand in front of the window to listen to the music and eventually this area turns out to be now a nature education classroom for the kids in the village to come and learn some science and nature.

This is the story from Shenzhen about a living Sponge Space. It is fun and beautiful. We will continue to work towards building healthy cities through the integration of green infrastructure and people’s engagement. Thank you very much!

David Simon

about the writer

David Simon

David Simon is Professor of Development Geography at Royal Holloway, University of London and until December 2019 was also Director of Mistra Urban Futures, an international research centre on sustainable cities based at Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden.

The nature of cities can be interpreted in different ways, and “living space” has two complementary meanings. One is space for living, rethinking land use, density, and sustainability. Another is space that is living, nature and nature-based solutions that are part of the cityscape. Both concepts are essential to address challenges in public and shared space in cities.

There we work together to bring together people who are often on opposite sides—and there can be many opposing sides of urban conflicts—to work through the entire process of producing new knowledge and research and thereby to understand that basically wherever you are within the urban fabric, whatever role you play, whatever livelihood activities you undertake, what unites us is greater and more important than that which divides and separates us. That is the basic idea of co-design, co-creation or co-production. These processes are called different things in different contexts, but we use them interchangeably. They are all about building that shared experience—which we find really important. It is innovative. It is experimental and in some of the independent evaluation studies that have been done of our work, those terms keep coming up.

Moreover, participants in the individual research projects and in the governance of the process as a whole often articulate the idea of the Centre’s offices being a safe and experimental space, since the Centre is a boundary crossing organization, if you like, where people are able to step outside their normal work environments and speak and think and study and reflect more freely. So that’s another part of the answer. We have many different examples of this from our different city platforms and, similarly, at each stage of this conference, about how people are using and reinventing their existing urban space to make it more habitable and more livable.

However, I should also flag that over the next 30 or 40 years more urban areas in terms of number of inhabitants and number of hectares that will be built up, will be constructed through the ongoing processes of urbanization worldwide, particularly in parts of the world outside North America and Europe, than have been built in the history of urbanism to date. That is absolutely crucial in terms of the global sustainability equations. The underscores the points that the Peter Head was making in the first dialogue this morning about rethinking use of resources and thinking about Integrated systems approaches and the use of new technologies.

It’s also important in terms of how we imagine new urban spaces and places and build them to reflect our cultures, our environments and so on in a way that most existing spaces at least in the 20th and early 21st centuries have not done. That too is part of sustainability and livability. And in that sense, I should also draw attention to the title of “living space”.

That’s because—rather as was pointed out earlier on—the nature of cities can be interpreted in different ways. To me, “living space” has two complementary meanings. The one is space for living in terms of rethinking densities, rethinking land use mix, and ultimately sustainability, requiring that we redesign cities in more compact neighborhoods where we require less personal mobility and travel.

Even the discussions about new technologies, electric cars and all the rest, seem implicitly very often to operate from the assumption that more mobility is both necessary and good but actually, in terms of a more radical approach to urban resilience and sustainability, one could argue in certain contexts, at least, that less mobility is both necessary and good—so we need to have multifunctional neighborhoods in which we can walk or cycle. By other non-technologically intensive means of mobility, more of the facilities and income earning opportunities and neighborhoods and social networks and other resources that we rely on and we utilize within the urban fabric should be reachable.

But the second meaning of the term “living space” is again back to nature and nature-based solutions, not as an alternative to steel, glass, concrete, tarmac, wood, plastic, and all the other conventional and unconventional building materials, but very much as part of it. In other words, it is space that is living, and a number of the slides that Eliza just shown and that we’ve had in other sessions and will do for the rest of the conference illustrate that very well.

Hence we need constantly not only to think about the design of new spaces, but how we can retrofit, how we can redesign, and repurpose elements of the existing urban fabric that have either outlived their usefulness—through technological redundancy, for example—or are not socially and culturally appropriate to the needs and the priorities of different categories of often quite heterogeneous communities inhabiting not just individual cities, but the numerous neighborhoods or areas that make up the cities.

I’m sure we can pick up some of these points in the discussion. Thanks very much.

Elisa Silva

about the writer

Elisa Silva

Elisa Silva is director and founder of Enlace Arquitectura 2007 and Enlace Foundation 2017, established in Caracas, Venezuela. Projects focus on raising awareness of spatial inequality and the urban environment through public space, the integration of informal settlements and community engagement in rural landscapes.

In spite of some successful public space interventions in Caracas, we realized there was a larger challenge of overcoming prejudices and recognizing the barrio as part of the city. We began an initiative that would address changes in the urban culture, addressing the language used to talk about informal settlements and urban symbolic gestures in the city. It was a point of departure to educate people about the city and the political and social cost of such lingering prejudices.

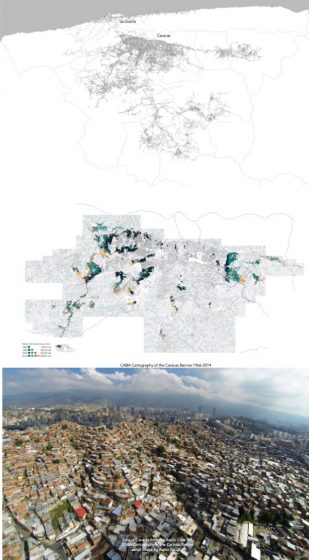

In 2012, we began a mapping exercise of the informal settlements and how they grew in a 60-year period. Informal settlements are the home of half of the population. That is, half of the city’s population lives in informal settlements. This was a key finding from this study.

In 2012, we began a mapping exercise of the informal settlements and how they grew in a 60-year period. Informal settlements are the home of half of the population. That is, half of the city’s population lives in informal settlements. This was a key finding from this study.

Within the discipline of architecture, the discourse focused on social housing, which isn´t a bad thing, except that several open questions remain. For example, what about the people living in existing settlements? And what about those who are still migrating from rural areas?

In 2012, I had the opportunity to do research and visit many informal settlements throughout Latin America. Time and time again, what I witnessed proved that public space had a unique ability to increase social cohesion and integrate these territories into the rest of the urban fabric. At the time of my research, neither Venezuelan local governments nor the State were investing in informal settlement projects. The opportunity to test the effects of public space interventions eventually presented itself through civil society initiatives. One example of work we did is an open-air waste dump sites such as one in La Paloma, where we were able to work with the community and change the space into a small public plaza together with a local NGO and the financial support of Citibank.

Part of the project also focused on engaging neighborhood children, through playful activities to think about and reflect on these spaces and their surroundings. For example, through a theater production, the children acted out the roles of various public space elements such as the sun, trees, cars, and shade.

Part of the project also focused on engaging neighborhood children, through playful activities to think about and reflect on these spaces and their surroundings. For example, through a theater production, the children acted out the roles of various public space elements such as the sun, trees, cars, and shade.

We were subsequently invited, because of this work, to be parts of an initiative with the Swiss Embassy and another NGO. We had the opportunity to help the community of barrio Chapellin recover a deteriorated public square. A curious anecdote is that they were resistant to include green areas within their public space and we were able to overcome this by creating an alliance with local schools, where the children were directly responsible for the upkeep of plants in the plaza’s planters.

We were subsequently invited, because of this work, to be parts of an initiative with the Swiss Embassy and another NGO. We had the opportunity to help the community of barrio Chapellin recover a deteriorated public square. A curious anecdote is that they were resistant to include green areas within their public space and we were able to overcome this by creating an alliance with local schools, where the children were directly responsible for the upkeep of plants in the plaza’s planters.

We were also able to create public space in an informal settlement used to park cars, by talking with the community of Las Brisas in La Palomera about transforming it into a public space. After negotiations with the car owners, a very modest children’s playground was built.

In spite of these public space interventions, we realized there was a larger challenge of overcoming prejudices and recognizing the barrio as part of the city. For example, streets signs indicate were formal neighborhoods are located. But, even if a barrio is right next to a street sign, it will not include the name of the informal settlement. Another example is that the quality of waste management services is very different for formal and informal city sectors. And so we decided to begin an initiative that would address changes in the urban culture. Addressing the language used to talk about informal settlements and urban symbolic gestures in the city, could be a point of departure to educate people about the city and the political and social cost of such lingering prejudices.

The program we started is called Integration Process Caracas. It began with a Manifesto to the Complete City, somewhat like the Dada Manifesto. It was read in public squares and published on online journals. It has inspired the lyrics of traditional music called decimas, which are rhymes, describing a city that includes all of its parts that we hope will sound on radio stations and become jingles people remember. We have printed fragments of it on T-shirts we use at our events. One form of recognition has been to acknowledge, for instance, the presence of bocce (or la pétanque in France) courts in the barrio. To celebrate them, have organized bocce games there, creating a setting were people play and share a space together, regardless of its location.

The program we started is called Integration Process Caracas. It began with a Manifesto to the Complete City, somewhat like the Dada Manifesto. It was read in public squares and published on online journals. It has inspired the lyrics of traditional music called decimas, which are rhymes, describing a city that includes all of its parts that we hope will sound on radio stations and become jingles people remember. We have printed fragments of it on T-shirts we use at our events. One form of recognition has been to acknowledge, for instance, the presence of bocce (or la pétanque in France) courts in the barrio. To celebrate them, have organized bocce games there, creating a setting were people play and share a space together, regardless of its location.

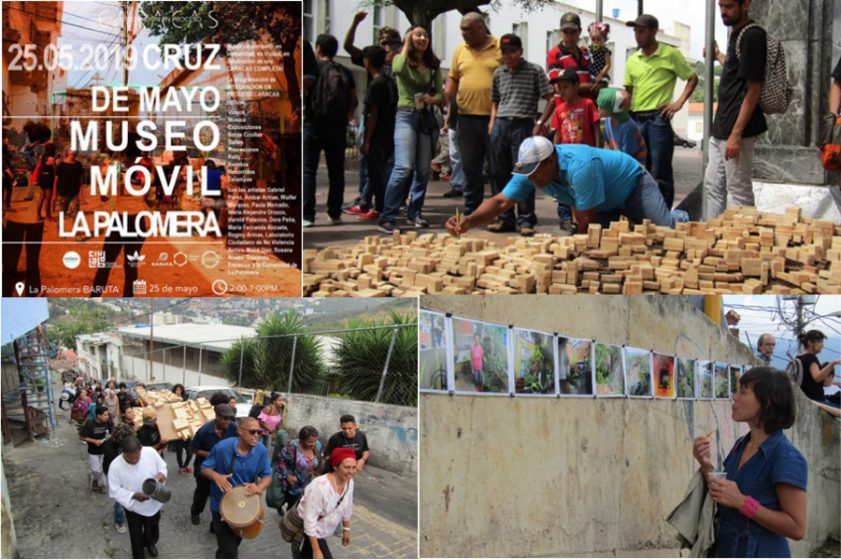

The initiative has amalgamated a constellation of artists and people from the community that allow us to spread the message further. One important event occurred May 25th, 2019. We celebrated the Cross of May, which is a festival or a traditional celebration. We combined it with a Mobile Museum, a procession through the settlement from the formal sector into the informal settlement, and an ambitious program of events and elements, including a large-scale model that allowed inhabitants of La Palomera to recognize themselves within their territory. There were performances by dancers and artists who worked with children from the barrio. And there were exhibitions such as a mapping and photographs of the barrio’s green spaces. Other artists led the celebration of the May Cross, and the San Juan procession with children from nearby schools. Celebrations that include music and dance, are an important way of creating cohesion among people. The community’s participation in the event was massive, as well as that of outside visitors. The celebrations and a long series of events with the community planned over the course of the previous seven months, have created a process that invites people to question perceived city boundaries between formal and informal sectors, and to expand their mental map of the city into one that is complete.

The initiative has amalgamated a constellation of artists and people from the community that allow us to spread the message further. One important event occurred May 25th, 2019. We celebrated the Cross of May, which is a festival or a traditional celebration. We combined it with a Mobile Museum, a procession through the settlement from the formal sector into the informal settlement, and an ambitious program of events and elements, including a large-scale model that allowed inhabitants of La Palomera to recognize themselves within their territory. There were performances by dancers and artists who worked with children from the barrio. And there were exhibitions such as a mapping and photographs of the barrio’s green spaces. Other artists led the celebration of the May Cross, and the San Juan procession with children from nearby schools. Celebrations that include music and dance, are an important way of creating cohesion among people. The community’s participation in the event was massive, as well as that of outside visitors. The celebrations and a long series of events with the community planned over the course of the previous seven months, have created a process that invites people to question perceived city boundaries between formal and informal sectors, and to expand their mental map of the city into one that is complete.

I would also like to introduce another question. What about the people that live in villages that still believe moving to a city is a way to improve their livelihood, or a way to send remittances home for their family’s benefit? For the past three years we have been working on a project in the southern part of Mexico in the State of Oaxaca. It is a region with a very important migrant population: 30% of its inhabitants live and work in larger cities or the United States. Mescal is today a spirit sold worldwide. I won’t go into details of how it is produced, which is fascinating, but what we know is that due to rising demand, production will have to increase tenfold over the next 10 years. In order to better understand how the resources used to make mezcal, (water, agave, and wood) can be supplied without depleting natural resources, and how to mitigate the effects of waste byproducts, we have been working with three communities in the area of Ejutla, south of Oaxaca city. Deforestation and water shortage are already serious problems in areas where mezcal is made.

They also have an interesting land use structure where much of the land in these municipalities is communal, due to agreements made after Spanish presence dissipated and as a result of an agrarian reform in the early 20th century. In the fall 2018 I led a design studio at Harvard University with students mostly in the landscape department. Findings led to understanding that the communal areas, which are underutilized (mainly for grazing and wood supply), but could become a very valuable asset for reforestation, wood, and agave production, as well as water harvesting opportunities. Instead of thinking of these fields the way tequila production has, as extensive monocultures of blue agave, proposals pointed to a mixture or species in the form of forests, wood harvesting, agave, and crops. As complex and simultaneous systems, the landscape becomes a has happened simultaneously and their complex in and showing how people land and all of the systems that are productive within them need to somehow enter into synchronicity.

I end with an image of a piece by Félix González-Torres titled “Perfect Lovers”, two wall clocks perfectly in sync with one another. Synchronicity is what makes them perfect. Synchronicity can happen between the land and the people, between city fragments in the city, as well as between people.

Leave a Reply