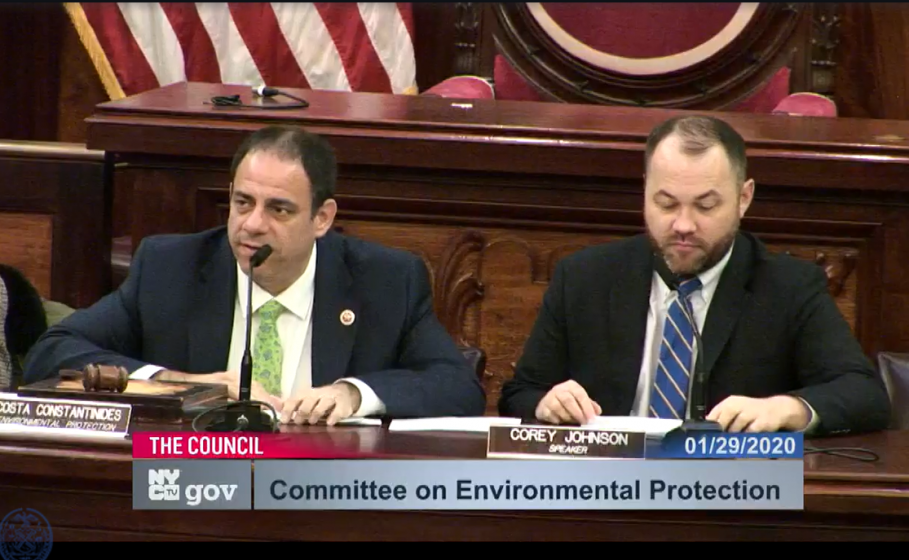

The idea behind these three bills is to tie the pending shutdown of the Rikers Island correctional facility to restorative environmental justice in the communities most impacted by incarceration on the island. Calling Rikers Island “a symbol of brutality and inhumanity” for many New Yorkers, City Council Speaker Corey Johnson opened the Renewable Rikers hearing with a full-throated support for the proposal. Not to be outdone, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced his intention to issue an executive order detailing a “participatory planning effort” for re-imagining Rikers Island.

The journey to this moment was more than a century in the making.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:USGS_Rikers_Island.png

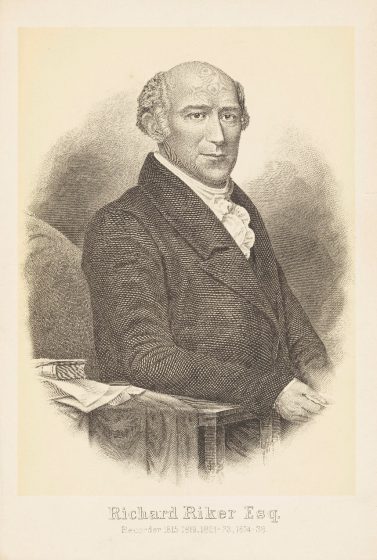

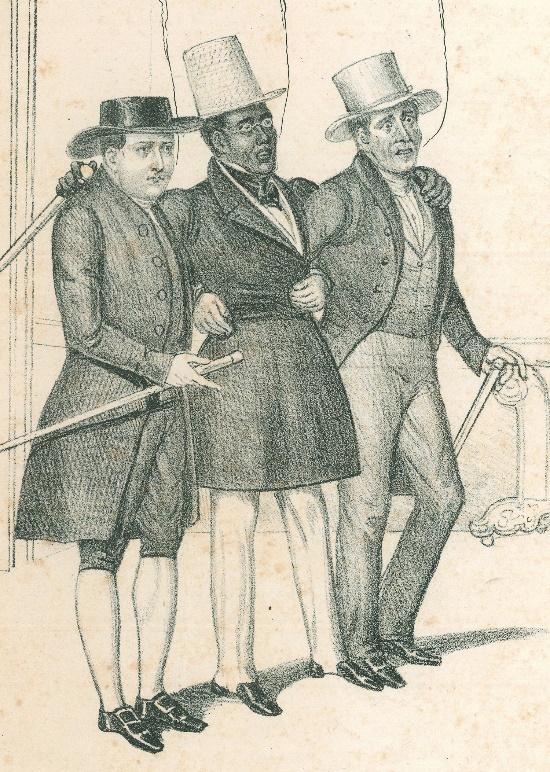

Part of the traditional territory of the Rockaway Tribe, the island bears the name of a slaveholding Dutch family (originally Rycken but anglicized to Rikers) who exploited enslaved people to build a fortune, which they then parlayed into social prominence. Yet even as the Rikers socialized with New York’s political elite, their name cast a dark shadow over New York City. Richard Riker, New York City’s first district attorney and City Recorder (the municipal officer in charge of the criminal courts) was infamous for abusing the Fugitive Slave Act and using his position to sell black New Yorkers into slavery.

Part of the traditional territory of the Rockaway Tribe, the island bears the name of a slaveholding Dutch family (originally Rycken but anglicized to Rikers) who exploited enslaved people to build a fortune, which they then parlayed into social prominence. Yet even as the Rikers socialized with New York’s political elite, their name cast a dark shadow over New York City. Richard Riker, New York City’s first district attorney and City Recorder (the municipal officer in charge of the criminal courts) was infamous for abusing the Fugitive Slave Act and using his position to sell black New Yorkers into slavery.

Abolitionist David Ruggles, head of the New York Vigilance Committee, frequently condemned Recorder Riker for his willingness to find that free New Yorkers were actually slaves, and for his role in returning escaped slaves to the South.

The parallel between Recorder Rikers’ conduct and the racially-charged abuses of power at the present-day Rikers Island correctional facility are striking. The era of mass incarceration saw black and brown New Yorkers imprisoned and abused at Rikers Island while for too long the white portions of the City largely noticed nothing amiss.

In recent years, Riker’s Island gained notoriety because of the shockingly high levels of violence, abuse, and neglect that inmates suffered there. In 2013, Mother Jones ranked Rikers as one of the ten worst prisons in the United States. Numerous reports and exposes documented gratuitous and excessive patterns of violence at Rikers, with force being used in a fashion “intended to harm rather than restrain and control inmates”.

The tragic case of 16 year old Kalief Browder came to symbolize the Lord of the Flies nature of the “cycle of unchecked violence” at Rikers. Browder was held for three years at Rikers, from 2010 to 2013, awaiting his constitutionally-guaranteed “speedy” trial on a minor theft charge. Browder spent two of those years in solitary confinement. Surveillance footage showed Browder suffering assaults at the hands of prison guards and inmates alike. When the charges against him were dropped, Brower was released. But his Rikers experience had been so traumatizing that Browder later committed suicide. Browder’s experience galvanized public calls for reform, and became a rallying cry for advocates bent on closing Rikers.

The next year, then-US Attorney Preet Bharara issued a scathing report on the “deep-seated culture of violence” among the guards and staff at Rikers Island. Bharara characterized the jail as “broken”, with a pattern and practice that violates constitutional rights. Bharara’s Report gave added impetus to a grass roots movement organized under the banner #CloseRikers.

Closing Rikers became seen as “a moral imperative”. The Report of Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform (the Lippman Report) characterized Riker’s Island as “a stain on our great City,” and recommended permanently ending the use of Rikers Island as a jail facility.

The Commission explicitly acknowledged that racial injustice played a significant role in the harms done at Rikers Island.

In Fall of 2019, New York City Council voted to close Rikers Island and replace it with four smaller jails by 2026. Mayor de Blasio declared “The era of mass incarceration is OVER in New York City.”

The Lippman Report called for any post-prison planning for Rikers Island to take restorative justice into account. The Report also raised the possibility that Rikers Island could contribute to the sustainability of New York City.

Starting from that rather vague suggestion, a coalition of scholars, politicians and advocates developed the Renewable Rikers proposal as a way to promote restorative environmental justice.

The proposal would dedicate Rikers Island to wastewater treatment and sustainable energy generation in order to phase out noxious facilities sited in the environmental justice communities most impacted by incarceration on Rikers.

After two years of work and advocacy, New York City Council held its historic “Renewable Rikers” hearing. Environmental justice groups, formerly incarcerated individuals, and various lawyers and academics testified in favor of the proposal. Nobody testified against it.

Closing Rikers will be a transformative moment for the City. Renewable Rikers could make that moment an environmental justice transformation as well. These proposed laws are a critical first step. By enacting them, City Council will launch a visioning process for truly restorative environmental justice.

Renewable Rikers is a path to a more sustainable, more equitable City. New York State recently committed to 100% carbon-free electricity by 2040. To reach that goal, the City will have to transition away from fossil fuels. Replacing the City’s dirty and aging Peaker plants with clean energy is a good start. Peaker plants are gas-fired power plants that only turn on during peak power demand. They start and shut frequently, rarely running for more than a few hours at a time. Startup and shutdown are the moments in which power plants emissions are the dirtiest. These Peaker plants disproportionately sited in marginalized communities, and their replacement is both an environmental necessity and a public health imperative. Peaker plants contribute to the localized air pollution that harms people’s health in overburdened, frontline communities. Some South Bronx neighborhoods that host Peaker plants have childhood asthma hospitalization rates double the City’s average. For example, pollution-related emergency department visits and asthma hospitalizations in Mott Haven and Melrose are triple the NYC average. Replacing dirty Peaker plants with renewable generation and storage on Rikers would improve air quality in these front-line communities.

Renewable Rikers is an opportunity to end an old, but ongoing wrong. For too long, New York City has disproportionately sited its polluting infrastructure in low-income communities and communities of color. The 2000 Power Now! Project is a clear example. The New York Power Authority used Enron’s engineered brown outs across California to justify adding 10 peaker plants in New York City on an emergency basis—running roughshod over frontline communities to do so. These plants were all sited in environmental justice communities with no community engagement, virtually no environmental due diligence, and over vociferous community objections. Although these plants were pitched as temporary, a 3-year emergency solution to a manufactured crisis—they are still there. Anyone born the year they were installed is eligible to vote and nearly old enough to drink.

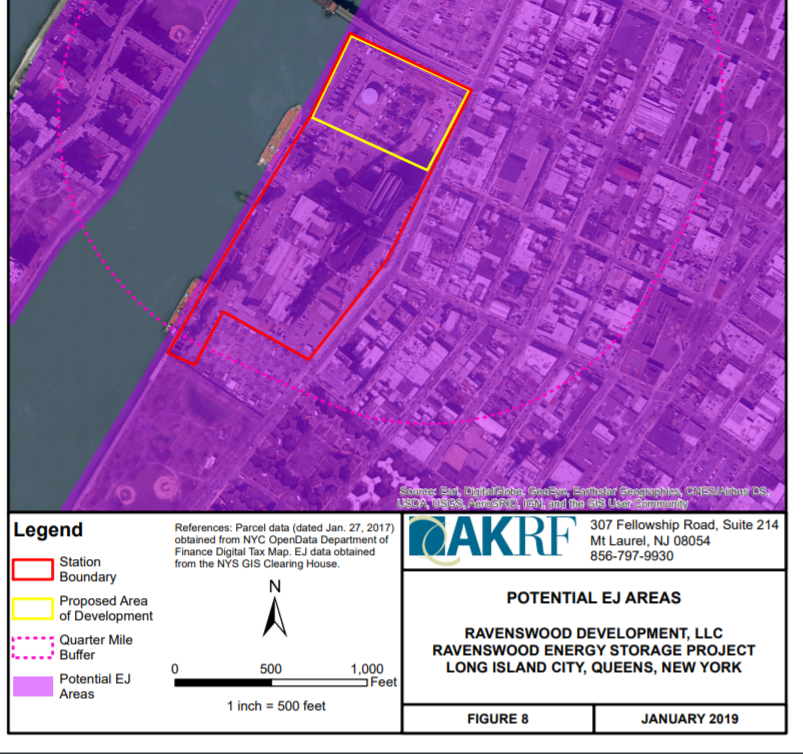

By seizing this opportunity to transform Rikers Island into sustainable infrastructure, New York City can right this old wrong. The Peaker plants could be shuttered and the land currently devoted to energy generation returned to these front-line communities for greenspace, affordable housing, or other locally-determined priorities. A recent Ravenswood power plant project shows that 316 MW of storage can be sited on 7 acres of land. Two such storage sites could provide more capacity than all the Power Now! plants combined.

By siting battery storage, solar generation, and wastewater treatment facilities on Rikers Island and moving these facilities out of environmental justice communities, Renewable Rikers leverages the transformation of the criminal justice system into wider transformation across multiple axes of justice. It benefits the City as a whole, while specifically benefiting the communities most impacted by mass incarceration, and incarceration at Rikers.

Enacting Renewable Rikers would be a moment for environmental justice. The proposed bills before the New York City Council would improve air quality for environmental justice communities, which are frequently the same communities most impacted by mass incarceration, and by incarceration at Rikers.

Enacting Renewable Rikers would be a moment for climate justice. The proposed bills would help ensure a just transition that reduces the burdens on frontline communities.

Enacting Renewable Rikers would be a moment for restorative justice. Solar installer and wind turbine technician are the two fastest growing job categories in the United States (albeit from a small base.) Renewable Rikers can create jobs with a pathway to prosperity for everyone—specifically for those most impacted by mass incarceration, and by incarceration at Rikers.

As plans for Rikers’ future mature, appropriate oversight mechanisms will be key to making sure that this project benefits the communities most impacted by Rikers and by environmental racism. Enacting the proposals currently before City Council would help ensure that closing Rikers does not devolve into a privatization land grab. The communities most impacted by incarceration at Rikers, and by environmental racism, must be part of the process. If these communities are consulted early and often, and that their representatives are part of whatever decision-making bodies will ultimately make choices about Renewable Rikers, it might indeed be the dawn of a new day for New York City energy generation.

Rebecca Bratspies

New York

Add a Comment

Join our conversation