In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Nature Based Solutions was known as design with nature, a term pioneered by Ian McHarg whose book on such principles was thusly entitled. Landscape architects like Ellen Spirn wrote about how cities needed to be designed/redesigned to take advantage of cooling breezes, sun for heating, vegetation for cooling, and more. But it was not until the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) that it seems such ideas began to take hold. The MEA was also underpinned by the quantification started by ecologists such as Robert Costanza and Gretchen Daily about the value of nature to the economy. This new turn created a fusion between ecology and economic value. Since that time, urban ecological science has been deployed to measure the attributes of natural systems in cities and their functions, such as CO2 sequestration, water retention, cooling by vegetation, and assigning monetary value to those services. Measurement and valuation have become normalized over the past several years. This has been accompanied by a quest to reintroduce nature in cities such that it could mitigate the impacts of the built environment whose construction so ruthlessly ignored place, climate, vegetation, rainfall, soils, and more. And now, the value of nature to cities can additionally be given a financial value to the economy.

Nature based solutions are being advocated to address multiple environmental and social challenges: biodiversity loss, mitigation of climate change impacts such as flooding, urban heat, improving human welfare, and addressing social inequality. For example, GrowGreen is a project funded by the EU Horizon 2020 program for Research and Innovation whose mission is to create climate and water resilient, healthy and livable cities by investing in nature-based solutions. It aims to embed nature-based solutions into long term planning, development, operation and management of cities. The program provides funds for cities to increase NBS by building parks or water retention facilities and other projects.

But, unlike traditional infrastructure—roads, bridges, sewage treatment plants—funding nature-based solutions (NBS) appears to be challenging everywhere, and seems to depend on, in Europe, EU funds. In the UK, there is a turn to attracting equity capital funding for NBS. Greater Manchester, for example, estimates a needed investment of 10 million pounds for a first phase of implementation of NBS. IGNITION is their strategy—Innovative financing and delivery of natural solutions. It calls for investible packages of projects to persuade businesses and organizations to invest in Nature Based Solutions. It defines investment in natural capital as Funding that is intended to provide a return to the investor while also resulting in a positive impact on natural capital (Greater Manchester Natural Capital Investment Plan 2019). The plan outlines key priorities and how the natural capital investment plan can help achieve them, including:

- Improving place (making Manchester more attractive and supporting an uplift in property values)

- Improving health outcomes by access to the natural environment and also redressing spatial inequalities in access

- Building resilience, especially to flooding and climate risks

- Supporting the local economy through regeneration toward improving the capacity to supply environmental goods and services

- Conserving and enhancing habitat and wildlife

- Sustainable travel (walking and cycling)

- Climate regulation

- Air quality improvements

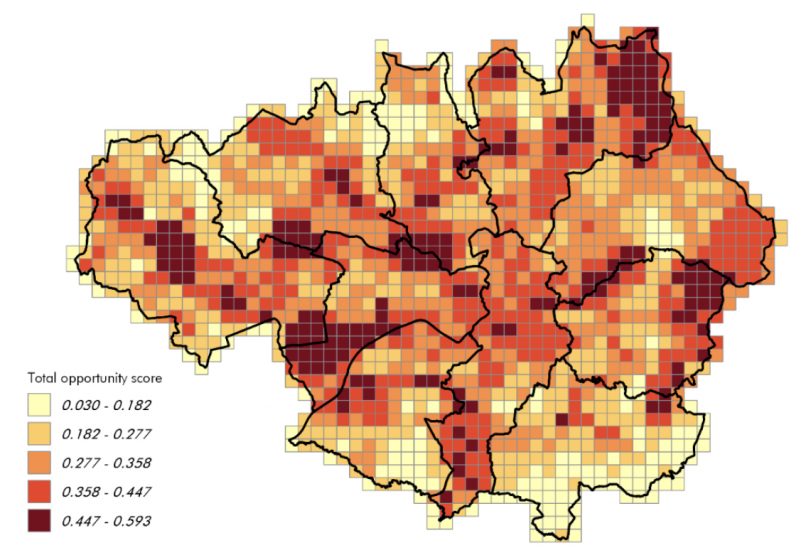

A map has been generated to target projects and map existing projects. The darker areas show highest opportunities, and they seem to track with the least affluent areas of greater Manchester.

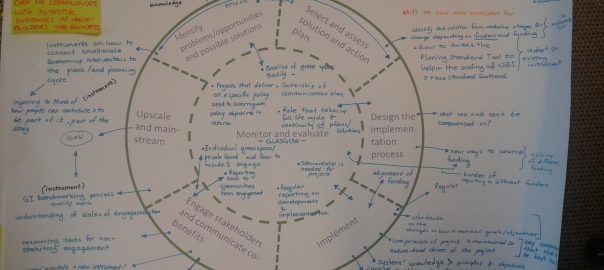

The plan looks at the roles for different types of investors and identifies the pipeline of potential project types that need investment; finance models to facilitate private sector investment and the role of the public sector, and recommendations to put the plan into practice over the next 5 years. The finance models are vague in the plan, but seem to monetize such things as leasing green and blue infrastructure assets to trusts which could then exploit new revenue opportunities such as through prescribed health activities (e.g. Doctor’s prescribing walking around a lake, and charging the health service for the access). Ironically, this in a country riddled with public and free access walking trails . . . the other potential source of revenue is habitat and carbon banking wherein credits from additional actions that increase biodiversity or stored carbon are sold to organizations whose activities cause unavoidable impacts. A third option outlined is furthering the already established Sustainable Drainage Systems through a reduced water company drainage connection charge for developments. This could then, according to the plan, be turned into a special purpose vehicle (SPV) that would deploy appropriate capital at different project stages, allowing the Sustainable Drainage System to be deployed and the cash flows aggregated to enable investment to be scaled up as part of the Water Resilient Cities Program. The public sector would serve as an investment commissioner, developing a supportive financial environment and business plans for specific investment opportunities. Greater Manchester would also have to create an Investment Readiness Fund that would come from foundations, corporations, Corporate Social Responsibility budgets, High New Worth Individuals, and philanthropists to provide specialist finance, legal and other skills to help develop business plans for natural capital projects to improve their presentation to investors (pages 8-10).

The goal is to increase Greater Manchester’s urban green infrastructure by 10% by 2038 over the 2018 baseline. The University of Salford Campus living lab will demonstrate the potential real world returns that result from such an approach through the development and monitoring of the impact of green infrastructure on buildings. Funding models and finance mechanisms to deliver phase 1 of the Greater Manchester NBS pipeline will be established by April 2020. Tenders for investment by equity capital will be then be offered to build the NBS in Greater Manchester.

At this point, solutions include rain gardens, street trees, green roofs and walls and development of green spaces. The Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) explains in its official documents, that these technologies can help tackle socio-environmental challenges including increases in flooding events, water security, air quality, biodiversity and human health and wellbeing. But they need to be financed.

Currently the planning project is backed by €4.5 million from the EU’s Urban Innovation Actions initiative, and brings together 12 partners from local government, universities, NGOs and business. The aim is to develop the first model of its kind that enables major investment in large-scale environmental projects which can increase climate resilience. It is all predicated however on successfully attracting investments.

The EU Directorate General for Research and Innovation advocates the use of NBS for urban regeneration to improve the well-being of residents, for coastal resilience, for watershed management. A 2015 EU report of the Expert Group on “Nature-Based Solutions and Re-Naturing Cities” of the Horizon 2020, emphasizes the importance of NBS infrastructure for investment as “it is cost-effective and demonstrates financial advantages due to reducing initial capital and operational expenses” (p. 6). The peculiar thing, if you think about it, is that conventional development—which this is implicitly to remedy—is, of course, not quantified for its costs to NBS, human health and well-being, urban heat, and its other impacts. Why is it that nature must be financially rewarding against an obviously destructive BAU? How is it that the BAU is not penalized for the destruction of the NBS when it is put in place?

Urbanization processes are ever expanding, yet the NBS approach seems content to attempt to retrofit existing urbanized areas cost-effectively and returning profit to investors. If the impacts of contemporary urbanization are as significant as claimed, and they probably are, then the remedy is not cost-effective retrofits of nature in the city alone. Clearly the patterns of urbanization, building materials, and land transformation processes need to change too, but this seems rarely addressed. Rather, these are patches of interventions that must not cost the public sphere any money (as it has none), but indeed, must be profitable and make business sense, just like the original development that caused the destruction of NBS did. At the same time, development must go on to provide economic growth. In fact, Manchester is in the middle of a building boom, high rises underway dot the city, allegedly financed by Chinese capital. Who will occupy the space remains a mystery, but meanwhile, a lot of money is being invested in the built environment that does not seem to reflect any NBS principles.

Cities in the 20th century, as mentioned above, have been built according to modernist engineering guidelines and concerns, and using hydrocarbons to overpower place – cold, heat, rain, wind, natural topographies, rivers and streams. It is amazing what big machinery can do to level mountains, fill in wetlands, and construct new urban areas, heated and cooled with fossil energy. Land use patterns are thus increasingly similar because they are all predicated on the same economic assumptions and power source – fossil energy. We find big box shopping malls, endless single-family suburbs all ribboned together by roads nearly everywhere. In China, single family homes are supplemented by gigantic apartment buildings. But in the end, the land, the place and its specific NBSs, are not integrated into the development. And post hoc remedies must be implemented, at a profit.

NBS should not be an investment opportunity any more than is a sewage treatment plant. If NBS do contribute what is claimed, then clearly land use that impedes them should not be permitted. NBS needs to be infused into building codes, zoning and land use guidelines. Any new building should have to protect and enhance them, de facto, any redevelopment should similarly have to protect, enhance, rehabilitate NBS. This is not a new investment opportunity, it is a matter of health and safety. Just like there are codes for safe electrical wiring in buildings that are not contested (generally!), ensuring that water reinfiltrates into the ground should be a matter of code, or the provision of open space, or trees. That builders must adhere to certain provisions like providing plumbing in their buildings clearly must extend to the creation/recreation/rehabilitation of NBS in the existing urban areas. And the transformation or destruction of NBS must be addressed by regulation, fined, penalized and made illegal. It makes no sense to invest in urban NBS while losing it through careless new land development. No loss of NBS would be one metric. In fact, it maybe that there should be no new land conversion at all. Rebuild, densify, with nature.

Of course, there is the additional question of whether proposed NBS actually produce the services claimed. To truly know if they do requires extensive and expensive monitoring and evaluation. Each site will be different, designs developed that work there, and the NBS will need to be followed over time. NBS is, regretfully, not one size fits all. Slope, soils, hydrology, microclimate, aspect, contamination and more, all matter. And so, while NBS is seen as a relatively inexpensive—or rather cost effective—way to improve the performance of cities and remediate the impacts of land development, the monitoring and evaluation is not integrated into the costs. Nor is the potential of the NBS needing to be changed, or it not working at all. Design with nature is not about cost effectiveness. It is about recognizing the unsubstitutable human reliance on nature and creating the conditions for its success. Such commitment needs to be embedded in urban development and redevelopment, and the private sector which is largely responsible for that activity, must integrate NBS principles as a matter of course. Where they have been damaged, the developer must pay. Ultimately the health of nature is human health though we act as though it is other, outside of our lives on the planet. NBS could be a way to reconnect people to place, cities to their locality, but a mechanism that relies on equity capital to make a return on investment to create them seems desperate indeed.

Stephanie Pincetl

Los Angeles

Add a Comment

Join our conversation