A review of Min Joung-Ki, an exhibition of large-scale urban nature paintings at Kukje Gallery in Seoul, South Korea.

Founded in 1982, Kukje Gallery is one of Korea’s most prolific exhibitors of international contemporary artists. Indeed, the institution is more of a small arts complex than a gallery, consisting of three modern buildings positioned gingerly within the fabric of an old urban neighborhood on the edge of Seoul’s ancient seat of power, Gyeongbok Palace.

Min’s paintings intensify thousands of years of human history, and relationships with nature in Korea’s capital city. For example, the varied story of Seoul’s famous Cheonggye stream, is offered here … seen out the windows from inside a simple barber shop.

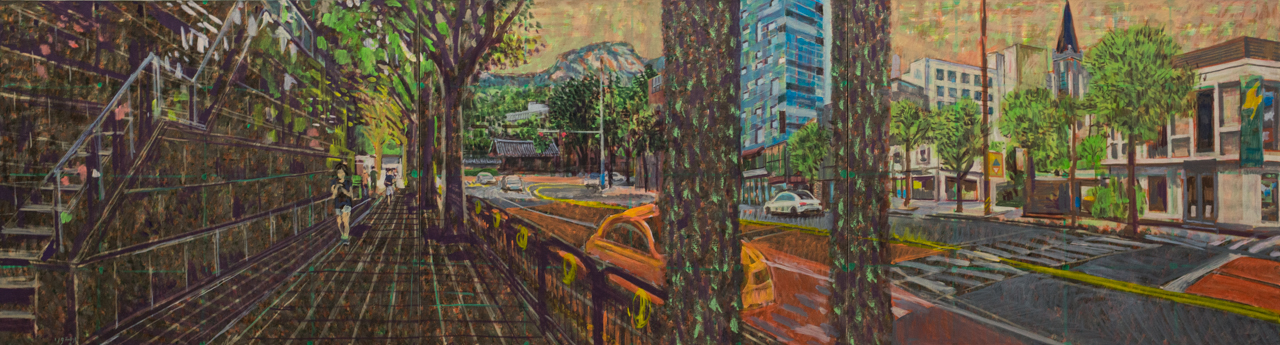

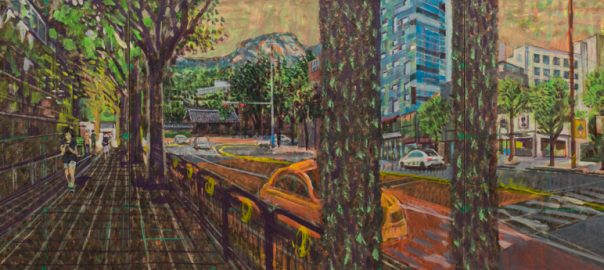

Works such as “View of Sajikdan at a Distance” present us with a typical Seoul thoroughfare, though the tree-lined street appears at first drab in color, smoggy, and somehow eerily dark. Min’s use of vivid color hides from us at first. On closer examination, we notice an undercurrent of clear, broad strokes of vivid, dayglow oranges and iridescent greens. This color treatment reappears often, and within it likely hides something of Min’s views about the nature/culture divide.

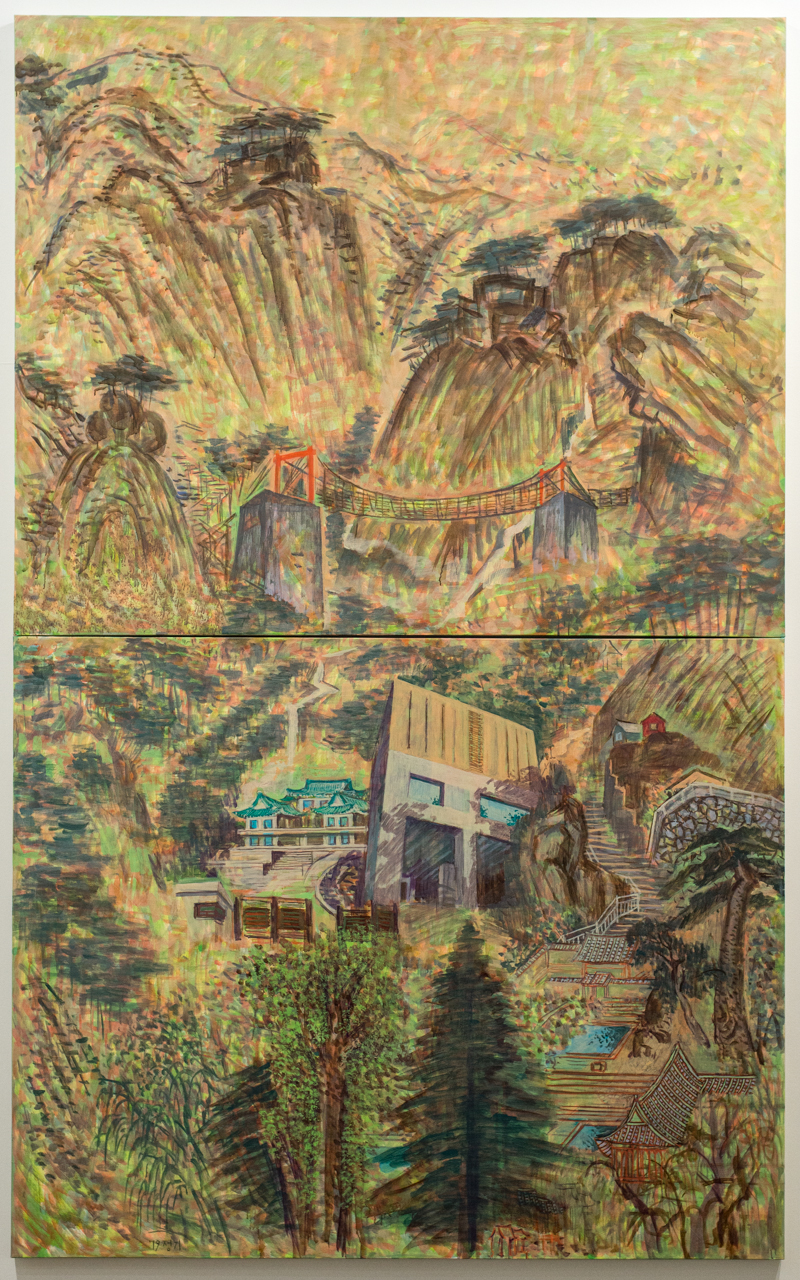

The physical situations that Min chooses to portray serve to intensify thousands of years of human history, and relationships with nature in Korea’s capital city. Many of the paintings here—modern buildings mingling with mountain Buddhist temples, both placed along winding stairways up and into mountain peaks topped with wiggling Korean Red Pine trees—show Seoul at is finest.

Though these depictions come across as unreal, they do in fact exist in the current day city.

Familiar though the settings may be, stylistically these works place us in between worlds. Though most of these works feel light and bright, there is also an overwhelming dimness, a brown haze that infuses the scene. Min accomplishes this with exquisite subtlety, in a way that the effect is almost there, yet almost not. The longer you spend with these works however—especially his most recent works—the more a distinct tension, and even sadness, comes out in the color palette he chooses.

If one has just stepped into the gallery from Seoul’s seemingly omnipresent smog, the overall feeling of these works will not surprise. In the past year, the city has seen only 25 days where the air quality could be considered “good.” In air quality surveys, Seoul continually ranks among the worst in the world.

If we look back a decade in Min’s paintings however, we find that his paintings weren’t always bathed in the dim brown.

There is much wet green in Min’s portrayal of Guiyuyean Pond, not only wet in what it portrays, but in Min’s technique, a thick application of paint leaves the canvas literally dripping with glistening green. It gives the viewer relief. One of the few scenes here painted outside of Seoul, it seems one of the images that viewers stop and stay with the longest. Staring into the lush depths of this pond, reflecting a cool blue sky.

It’s something of a healing experience.

Water is a reoccurring theme in this exhibition, and indeed one of Seoul’s most well-known urban waterway projects is featured here. Many urbanists know well the story of Cheonggyecheon. During Korea’s rapid urbanization in the 1970s and 80s, this storied stream that runs straight through the core of the old city center was buried beneath a highway, only to be bought back to the light of day a few decades later. The varied story of Cheonggye stream, is offered here in the spirit of Korean poet Park Taewon, seen out the windows from inside a simple barber shop.

The series of three paintings, arranged side-by-side, explore the changing view of Cheonggyecheon over what appears to be a century, as the stream develops from a place of commerce and trade, to a highway construction zone, and finally as it is today, a social gathering space for citizens and tourists.

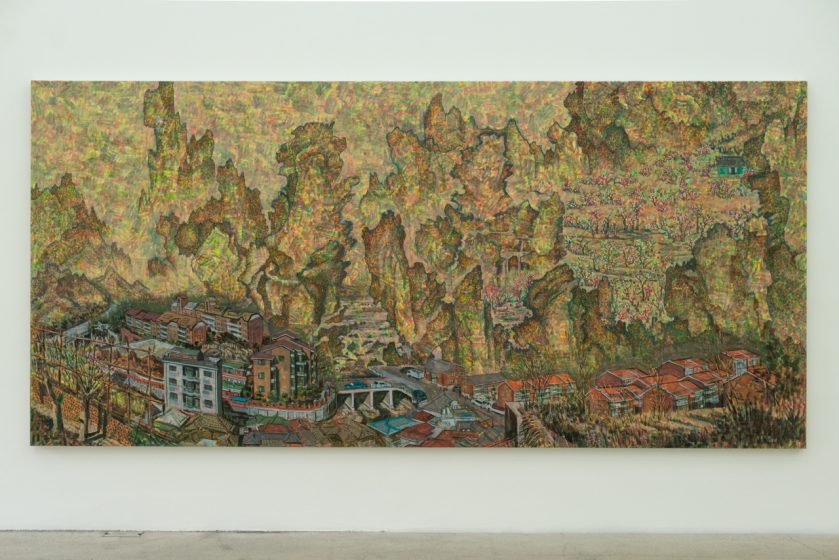

It is not until we reach the final room of this exhibition, that we encounter what is perhaps the defining work, a soft-yet-monumental piece that ties Min’s sentiments together. The divide between the “otherworldly” life of nature, and the concrete nature-devoid lives we tend to inhabit in most cities could not be more clear than it is in “Roving Mongyudowon”.

Here, tree-like mountains—or are they mountain-like trees?—act as shapes, morphing into the atmosphere, slightly unruly orchard blossoms fronting a brightly-painted traditional house, iridescent water flowing magically down through the entire scene.

And then it all stops.

Abruptly.

A concrete bridge for cars, walls of brick and mortar below, a scene solidified, a completely different world than the one above. What Min portrays above seems like the heavens, shapes of the universe; what he paints below, the comforts of our daily reality, come across here as a structure-obsessed life.

The colored water stops its magic at the vehicle bridge.

The broad strokes of bright greens and oranges that dance wildly in the skies and mountains, is covered here, with solid layers, roof tiles, streets, walls; traces of the elusive radiance peek through only in a few areas of unkempt urban weeds.

Through all of this, however, one is still never quite certain where Min’s heart lies, never certain if the paving over of these colorful gestures leaves us at a gain or a loss. His work on the whole plays with dualities, being at once graceful and powerful, loud and peaceful. Both urban and natural scenes elicit beauty, as much as they also lend us emotional quandaries.

In treading lines so lightly as Min does though, he leaves much room to question our own feelings about these scenes, about the interplay between nature, culture, and our urban structures, and too, about the history folded up so deeply within these elements.

In a city so rapidly developing as Seoul—and where development often comes at the wholesale destruction of thousands of years of culture and billions of years of nature—Min’s works might at first come across quaint.

Yet perhaps that is part of the power and magic unfolding here; paintings that allow us to access and contemplate the undercurrents within deceivingly simple scenes. If we spend enough time with Min’s work, these qualities offer us welcome room to contemplate not only what our cities were and are, but in turn, what they might become.

Patrick M. Lydon

Osaka

Leave a Reply