about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

How can professors better mobilize academic knowledge? How can professors get more engaged in practice knowledge? Or, in the prompt’s most provocative version: how can professors get out of the ivory box and into the streets? This was the theme of one of the Dialogues at The Nature of Cities Summit in Paris, with scientists and planners Thomas Elmqvist (Stockholm), Nina-Marie Lister (Toronto), and François Mancebo (Paris), and moderated by David Maddox (New York).

Scientists produce lots of knowledge, certainly. Is it connected to the practical needs of cities? Are scientists connected to practitioners in ways that produce useful co-productions? Well, yes and no. Most of the people at TNOC Summit would be deeply sympathetic to the idea of transdisciplinary co-production that includes academics. But it is not the norm. How might we make it the norm? What prevents us from doing so?

There were two common themes. One is the key idea of trust between scientists and practitioners. Trust is largely build over time, and with the shared understanding that ideas, credit, and benefits will be shared.

A second theme is the fact that academia is not good at incentivizing collaboration outside the academy. Reward structures are not build to credit work outride traditional scholarly venues. Long publication times are not conducive to the rapid needs to decision makers. Non-academics are rarely invited into the decision making of university leaders.

But there are ways forward, and the three speakers included here are experienced at created new venues for collaboration.

At TNOC Summit, we largely avoided long presentations in plenary—i.e. “Keynotes”. Rather, even when we gathered in our largest group, we met for “Dialogues”, similar to the Roundtable format at TNOC. For each dialogue there was a core question or prompt, such as the one in this Roundtable. We invited three people to participate, striving for a multi-disciplinary group, with diverse points of view, perspectives, and approaches. Each of the three delivered a short intervention (about 8 minutes), and then sat together for a longer conversation. We are publishing all of the Summit dialogues in oder to make the ideas widely available and keep the conversations going beyond the Summit itself.

In this Roundtable, we present both their written texts (essentially a transcription of their presentations) and video of their presentations. Also you can find a transcription and video of the conversation below.

A transcription of the conversation

David Maddox, moderator: Fantastic. Fantastic. The somewhat provocative title that we have was about getting professors out into the streets. Another version of the title is how do we mobilize knowledge, or even how we might democratize knowledge? So, if you can imagine one thing you would change—whether it’s a reward structure or whether it’s some sort of engagement patterns or … —what is one thing you would suggest we could do to change the current state of lack of engagement between these different sectors. Absolutely many people and many people in this room do this, and you guys are great examples of people who do this kind of co-production. But it is not the norm. So, how do we make it the norm? What is the one thing we could do to make it the norm Thomas?

Thomas Elmqvist: Well, I think this conference should be one thing. You have to make it a fun event. It must be very enjoyable to be engaged. We really need to think carefully how we design this to get people to talk to each other and engaged in a way that feels enjoyable and productive and gives hope for the future.

Nina-Marie Lister: Give university tenure to young people who are employed part-time in municipalities federal government, provincial government, and the university. Why? Because it fosters long-term research. And, by the way, Thomas you inspired me to answer it this way because we have no reward structure for the incoming generation of professors who do this kind of work at all. At least not in North American universities. You have to be something else before you are everything. And we don’t have time. And it’s not to say that I don’t value the enormous depth of research that science does. I’m still a recovering ecologist. I still respect the data. We use it all the time in our work, but we cannot spend time being duly certified in two or even three professions before the university system rewards us to communicate our knowledge in meaningful ways with our publics and our cities simply. When they do cross appointments with university… that’s just called having two jobs, people. That’s not good enough.

David Maddox: And why would we get the universities to accept that sort of change in the reward structure?

Nina-Marie Lister: Maybe they need to start counting the money that a lot of us are bringing in with our NGO Partnerships and work that we do with The Nature of Cities, which frankly doesn’t count in the academy.

David Maddox: Although I am gratified that some people I know, I think Timon [McPhearson] might have been the first one to actually use The Nature of Cities publications as part of his tenure review. [Laughing] I think he was denied tenure, wasn’t he? No. No, he wasn’t of course. He got tenure. Francois?

François Mancebo: Yes, to carry on with the metaphor: let the giant into the room. Basically, as an ecologist as well as an urban planner, and I have the feeling that when try to address an issue it is important, to involve from the start everyone concerned in the answer that will be given to his issue: all the stakeholders, residents, inhabitants. We have to get them into it and accept their common knowledge is significant and makes a lot of sense. I remember a colleague of mine working in Bangladesh. They were developing a program about how to protect areas from floods, using people’s common knowledge. Traditionally, when people saw sand-worms get out of the sand, it meant that flood was coming in within a few days, so they moved. So simple. But it was very difficult to make local scientists accept this common knowledge was more adequate than their expert knowledge about flood in this specific situation. More so to include the people who had this knowledge within their research.

I think that it is about building trust. It is not just a professor going out the “street”. It’s also about the “street” getting involved all along in the research. It is promoting more inclusive action research. Today, I have the feeling that the more we speak about going out and doing action research, the more we paradoxically stick to our own kind and our way of thinking.

David Maddox: Many people on this stage have talked about the idea that building trust in collaborations is a key factor, maybe the most important factor, and so from your side of the equation, as professors who are trying to build collaborations beyond academia and be useful in policy and planning from your side, what builds trust for you? And maybe on the flip side of that is what do you do to demonstrate that that you are trustworthy as a partner?

François Mancebo: Basically, people are very pragmatic. Inhabitants and NGOs want more decision-making power on their lives, scientists need some ideas and topics that they can develop in their own field and increase their recognition. Thus, any stakeholder that is not considered to have the provide what they expect and can be useful for them in real life, lose legitimacy even if he has great expertise. Then action research doesn’t work. How do you say: you are f****d, pardon my English. Thus, legitimacy has a lot to do with trust, and you build trust through common interests. Making sure that if people trust you then they can have something in return that would better their life. A research is not just a report that will end in a drawer, or in a publication. It has to have consequences in their life, and positive ones.

Nina-Marie Lister: We use Rules of Engagement that are fair for everyone. We don’t take more than we give. We reference and give acknowledgement to our community partners all the time. We make sure that if we’re working with vulnerable communities, they tell us what they need, not us telling them what we will give. So, some of it is what I would say is courteous. The other is what would be contractually, ethically required. We make sure that we are available for information to be asked of us. We share everything we make. We don’t keep it and we never publish or photograph without permission. So some of those are really basic rules.

The other thing we do is something that Thomas has already mentioned. We try to have fun. We try to host dinners. We try to go out into the community and have our students and our researchers working together with community members in a personal way, much as I think The Nature of Cities does to build trust. I don’t think I’ve ever received funding for a dance party though. So if anyone’s got a line on that, let me know.

Thomas Elmqvist: Well, just a few words to compliment. I think on building trust, one important part is to really show that you have a long-term engagement and that there’s something that is a joint goal you want to achieve in the long term. And also that there is some sensitivity of any asymmetry, whatever it could be in power resources and to address that asymmetry in a sort of in a trustful way.

David Maddox: And, I guess this could go for any kind of collaboration that you might build, what else, beyond the question of loss of trust, are the most common things that go wrong? What can go sideways in collaborations when they don’t work. I know there’s a long list of things that can go wrong, but what if…maybe the question should be: what are the things that could go wrong that that wouldn’t have to go wrong as much if we planned better these collaborations.

Nina-Marie Lister: Where to start?

David Maddox: Nina-Marie’s mind explodes.

Nina-Marie Lister: Okay, just one thing would be the ill fit between community-based research partnerships and co-design / co-creation with traditional universities bureaucracies and their own siloed way of thinking, based very much on a kind of linear reductionist accounting that makes it very difficult for us to do things that are kind or nice for our partners. I mean, I used the example of a dance party, which is not really a line item on my grants right at the moment, but even for us to do things like pay honoraria to indigenous Elders with whom we work is a difficult thing to do and it takes so much time and energy from us, away from the good work of collaboration. So that you end up feeling simply clobbered by the work and it can be very draining. These are [individually] very simple things, one by one, but they stack up and they consume an enormous amount of oxygen, energy, and time.

David Maddox: So, the rules are stacked against you, against anything that’s unconventional.

Nina-Marie Lister: Absolutuely.

David Maddox: Even if you want to do it that way and everybody else wants to, the rules are stacked against you?

Thomas Elmqvist: Yes, one other thing we know is that a lot of projects fail and I think one way of handling that is important is that maybe you already from the start have the attitude: Well, we’re doing this together as an experiment and, whatever comes out, it will be a learning experiment rather than the feeling of sort of a joint failure, which I think could be a legacy that it’s hard to get over.

François Mancebo: Yes, and it is a matter of adaptation to structural perturbations. More than often, as researchers, we are on our track and anticipate from the beginning what what we are searching, how we are going to search it and what we are going to find. But in real life there is political struggle, personal interests, it is completely different. Besides people change constantly. Things are not the way they were supposed to be. And sometimes, we don’t adapt fast enough. It is about our incapacity to adapt to chaotic situations. And it is really weird because at the same time we expect that the people in the street adjust to us and our methods, but we don’t adapt to them and their needs. It is very difficult, and a lot of research fails on that basis. We listen, but don’t really hear what is going on.

Nina-Marie Lister: I’d like to follow up on the idea about failure. We have written a lot about the idea of “safe to fail” experiments and design so that when they do fail, they’re not catastrophic and nobody gets hurt. But I’m not a bridge engineer. So, I’m allowed to talk like that. But I have to say, nobody rewards me for failure and there’s a lot of them [failures]. I mean some of you in the academic world might know about the CV of failures. It’d be a nice idea, rather than showing us your impressive CV, show all the things you tried and didn’t get. I would like to develop a casebook of failures for community-based partnerships because, boy would it be a great learning tool! But there is so little incentive to talk about your failure publicly. So that’s another thing we could do.

David Maddox: It feels like an another element that is stacked against these kind of collaborations is the length of time it takes to publish the work. If the work is very alive and on its feet, and you’re going to be writing about it but it’s not going to appear for a year, year and a half. For the practitioners it is really frustrating. Can that be changed?

Nina-Marie Lister: That’s why I would advocate for different models of tenure that allow for our community-based practice and co-design to have evaluative formulas. We certainly say that we value, in my university at least, experiential learning. We value scholarly research and creative activity. And those of us that are in the creative design disciplines and in the arts have [different]models for tenure as well. But they’re an ill fit. One of the ways to do that is to begin to change those formulas, and that means we have to sit on tenure committees. But sometimes we may be the lone voice that’s advocating for work that’s being done as valuable in tandem, with different kinds of peer adjudication.

Thomas Elmqvist: One other mechanism to address this could be: some journals have already started a sort of pre-publication process. You can put out your preliminary paper with the authors being fully transparent and that is open for comments from a wide community. And then the preliminary results can be used in some sort of process. Then that open review process and maybe some other more formal review process will eventually result in [a decision on] whether this paper will be accepted or not. But you still have some process where it’s out there discussed and scrutinized and the results could be used [immediately].

François Mancebo: One big problem is that officially there are incentives for interdisciplinary research—at least in France but I guess it is about the same everywhere else— more multi-disciplinarity … blah blah blah. But in fact, everybody keeps working inside his disciplinary field. Not that much when you are a city planner scholar, who is constantly involved in action research, but go meet a biologist, a chemist, or lawyer and ask him: “Hey come and work with me on this matter, it’s quite interesting”. What does he usually answer? “Well, they’ll never publish what we will do together. We won’t have any incentive for that. I’m not going to be recognized.” This is a big problem: sectorization. I would like the emergence of a synthetic, multi-disciplinary field, but it looks like it is not going to happen soon.

Nina-Marie Lister: Well, some of us just make a concerted effort to publish in applied sectors, or we publish our work in policy.

David Maddox: Questions?

Question from the audience: Thank you very much really stimulating session. My name is Polly Mosley. I went as a mature student to start PhD two years ago after having worked with the community one mile away from the University for 10 years. My question is about ethics. I think for me in a Natural Sciences Department, I found ethics a massive hurdle to get out and actually start the research. I think we need a new land ethic and I think the university’s role in our city is massive. It’s a massive land owner. Its Estates Department puts plastic trees in our foyer. We have enormous impact on city life. It calls itself and modern civic university, yet it feels like it is designed to break down trust with communities, to stop adaptive behaviors that can build on trust that’s already there, and the local feels a lot less easy to talk about for the natural scientists than the global, far away issues. So, I just wonder how can ethics be used in a much more positive, bridging way. I feel it’s really key to research.

Nina-Marie Lister: I would just like to ask a clarification question when you say ethics. Do you mean an ethical imperative for the University to bridge those gaps or do you mean research in ethics as a tool? Okay. Can you sit on the committee? But that really is of course the solution, in a serious way, that more people who are doing interdisciplinary, practice-based research have to be on those committees and that does take time and you’ve heard me say certainly and others echo in different ways, that we don’t have a lot of time. So we have to find some way of being creative to use existing rigorous methods that take a long time, that take turn around time, and journals combined with those universities that have an imperative for either community-based practice research. You often find it in the health disciplines. You’ll find it in the artistic disciplines sometimes, so there are strategic connections one can make with those departments.

This is not advice that I would necessarily give to untenured faculty. It’s much harder for you and for them sometimes. I think that’s our responsibility, for those of us who have tenure and are already on those committees. We need to take that up and make it very clear. And besides we can be as irritating as we like.

François Mancebo: I agree completely with what you are saying. Unfortunately, I think it’s not only about being in the committees. I am vice-rector of my university, with a special focus on sustainability. This is what I am supposed to do, but every time you try to achieve something in this direction… good luck. So, it is something that has to come in the long term.

Question from the audience: My late mother was an urban Anthropologist and Professor but also very much an advocate. If you wouldn’t mind, talk a bit about the role of professors as advocates going beyond the Ivory Tower out into the community and maybe taking a stand on something that could be political, could be about the subject manager research where you go out on a limb. Have you done that? And what do you think about that?

Question from the audience: I’m glad that you changed the title from getting me out of a box. I was feeling a little bit coffin-like. I was in my Ivory box earlier. I just wanted to suggest that perhaps there are some University environments and indeed national research cultures where this work is actually now pretty much institutionalized. For better or worse, actually. If you speak to any UK academic about the RED—the Research Excellence Framework—you’ll find that at least part of our research evaluation, which is done periodically about every five or six years, is on how much societal impact we are having as a university. We are evaluated on that. It’s part of our promotion criteria, progression, tenure appointments, everything now means that you as an academic have to be doing this kind of work, to one degree or another.

But the problem is that nothing else has gone away. So you also have to do all the other things as well. I also have the pleasure of convening a Horizon 2020 project and it’s absolutely essential that this is the kind of work that’s done within Horizon 2020 or you don’t get the research funding so, all across European universities this is embedded in what they’re doing. The Australian research grants Council funding and the Australian academic culture is the same; increasingly so in The Netherlands. And so there is a lot of institutionalization of this at the moment for good reasons, but part of the challenge is how that then becomes institutionalized, how it’s evaluated, what kind of things get to count, and how it’s basically done on the on the basis of the Ivory Tower rather than on what the Giants or the communities might suggest would be ways of evaluating what was actually effective in terms of impact.

So, in some senses institutionalizing this … yes, but it’s maybe a little bit of a cautionary tale to be careful for what you wish for, because it doesn’t always actually mean that you get better research or engagement or practice out of it.

Nina-Marie Lister: I was just going to clarify that I don’t think I know of a North American University—I can’t speak so much for the U.S.—but aross the Canadian landscape, this is totally institutionalized by requirement. What I should say is it is disincentivized in terms of promotion for the very reasons you suggest, and when we look at—frankly, I have to say it—the gender breakdown on service that’s related to Community Partnerships, it is overwhelmingly women who do it and, we are on average ten years later to apply for promotion to full Professor. So there are enormous built-in disincentives. I agree completely.

David Maddox: Can you be an advocate in addition to your role as a scientist?

François Mancebo: Of course, a scientist is not an ethereal and neutral person, without sex or opinions. A professor is a human being, completely, including his own opinions. What you have to do ethically, is to declare clearly what your biases are and where you are speaking from. If you do that explicitly in the prologue of what you are writing, your readers can discuss with you, fight with you. And it is normal. What’s your position from the beginning? Just distinguish your belief and your motivation, and how it impacts your scientific work. You cannot be neutral.

Thomas Elmqvist: I just want to reinforce that I think yes, absolutely, you could take moral and important stands, but declare transparency in where you’re coming from. I think that’s that’s a very important part.

David Maddox: Last word to Nina-Marie.

Nina-Marie Lister: Urban advocacy is what I think a lot of planners are trained to do but do it in a way that makes clear what both my colleagues have already said. I’d also say that there is a moral imperative. We are facing a biodiversity and climate crisis combined. We have an obligation as public servants in anchor institutions in our cities that shape and form our cities. I think it is in our code of conduct in Canada as planners. We are morally required to do public good. So, for me, I will say all the time: my role when I wake up every day is to think about making an urban agenda for biodiversity conservation. So, anyone who’s here from CBD in Montreal, please come and talk to me.

David Maddox: Thank you to François, Maria-Marie, and Thomas.

about the writer

Thomas Elmqvist

Thomas Elmqvist is a professor in Natural Resource Management at Stockholm University and Theme Leader at the Stockholm Resilience Center. His research is on ecosystem services, land use change, natural disturbances and components of resilience including the role of social institutions.

about the writer

Nina-Marie Lister

Nina-Marie Lister is Graduate Program Director and Associate Professor in the School of Urban + Regional Planning at Ryerson University in Toronto.

about the writer

Francois Mancebo

François Mancebo, PhD, Director of the IRCS and IATEUR, is professor of urban planning and sustainability at Reims University. He lives in Paris.

about the writer

Thomas Elmqvist

Thomas Elmqvist is a professor in Natural Resource Management at Stockholm University and Theme Leader at the Stockholm Resilience Center. His research is on ecosystem services, land use change, natural disturbances and components of resilience including the role of social institutions.

Thomas Elmqvist

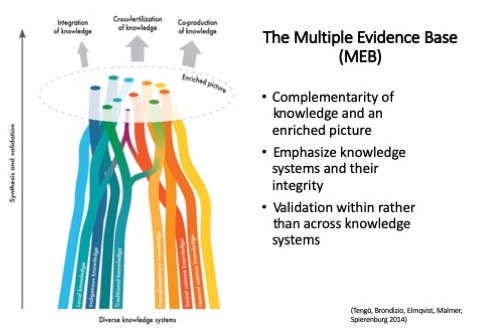

If we succeed to get a diverse set of people speaking to each other, coming from different silos, we will greatly enrich the picture of how we perceive the outside world. This illustration (FIG), which we call the spaghetti model, depicts how this may be done and how building a multiple evidence base could further strengthen knowledge exchange and knowledge generation.

There is valuable knowledge within as well as outside universities, among practitioners, among policymakers, among public servants, among local citizens. Knowledge is everywhere and constantly evolving and we need to find models how we may harness and use all that knowledge.

One important aspect in this process is the value of respecting each other and building trust and I think that’s the key for this to happen. It probably makes the process a bit slow. However, even though it will take some time to build trust, I think it’s absolutely essential for a successful process of co-creation of knowledge.

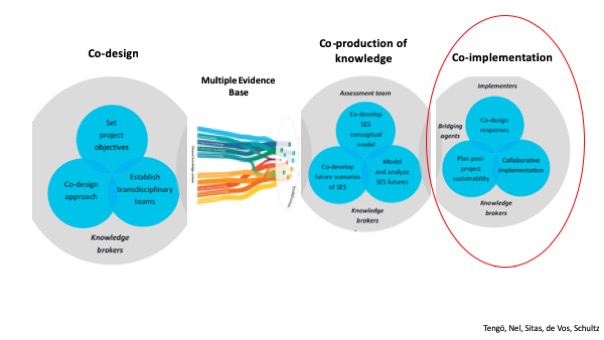

But even if we succeed, how do we turn this into action? How do we get the urban professor out in the street, doing something that is really valuable? An important starting process is co-design where stakeholders from different walks of life come together to design the challenge or prioritize among the problems they want to address. Then, the next step would be using a multiple evidence-base approach to come up with new knowledge that actually address and provide an answer. This step we may call co-production of knowledge. I’m quite optimistic and I think we’ve come quite a bit of on the way of doing this in practice.

But even if we succeed, how do we turn this into action? How do we get the urban professor out in the street, doing something that is really valuable? An important starting process is co-design where stakeholders from different walks of life come together to design the challenge or prioritize among the problems they want to address. Then, the next step would be using a multiple evidence-base approach to come up with new knowledge that actually address and provide an answer. This step we may call co-production of knowledge. I’m quite optimistic and I think we’ve come quite a bit of on the way of doing this in practice.

For example, we may look at how the incentive structure and the reward system in the Academia has changed during the last five or 10 years, it is very much in this direction, partly driven by funding agencies. Now, you are often requested in grant proposals to include a diversity of stakeholders and you are evaluated on basis of the extent you involve them in a deep and real sense. What I think is still lacking so far is mechanisms for co-implementation where you jointly with stakeholders work in implementation processes. Academic professionals may have a very important role in implementation, both in evaluation and monitoring, but I think this has been overlooked so far, for which there are obvious reasons. Currently there are no strong incentives for academics to engage in very long-term implementation processes. However, there are interesting examples, some municipalities are creating shared positions with the university researchers, with 50 percent position with the university and 50 percent with the municipality. This would better enable engagement in the whole process of co-design, co-production and co-implementation.

What I think is still lacking so far is mechanisms for co-implementation where you jointly with stakeholders work in implementation processes. Academic professionals may have a very important role in implementation, both in evaluation and monitoring, but I think this has been overlooked so far, for which there are obvious reasons. Currently there are no strong incentives for academics to engage in very long-term implementation processes. However, there are interesting examples, some municipalities are creating shared positions with the university researchers, with 50 percent position with the university and 50 percent with the municipality. This would better enable engagement in the whole process of co-design, co-production and co-implementation.

I think the question of how do we get professors out in the street, could be answered by that we are partly there and there are encouraging developments on the horizon. Of course there are challenges and barriers we need to overcome but I have quite an optimistic view.

about the writer

Francois Mancebo

François Mancebo, PhD, Director of the IRCS and IATEUR, is professor of urban planning and sustainability at Reims University. He lives in Paris.

François Mancebo

This is a tale about why professors are reluctant to go into the streets. From my own observations

Once upon a time, there was a professor named Jack who lived in a poor research center. His only means of income was a cow named “research funding”. When this cow stopped giving milk one morning due to budget cuts, he went into the street to sell his expertise. There, he met an old man who offered “magic” beans in exchange for this expertise. Jack took the beans but when he arrived at the research center without money, his colleagues became furious, threw the beans out of the window and send Jack to bed without supper…

What exactly is it about here? Legitimacy.

What exactly is it about here? Legitimacy.

His colleagues considered that going into the street and exchanging expertise for the beans of common knowledge, was not good deal: these beans could not possibly end in good science, and they sure could not provide solid funding. Thus, poor Jack lost all is credibility.

But wait: as Jack was sleeping in despair, the beans began to flourish into a gigantic beanstalk. In the morning all the research center started looking in disbelief at this huge and cumbersome production. This was not supposed to happen, they said. It doesn’t fit into our theoretical frameworks at all. Better look away and let Jack deal with this “monster”.

So, Jack climbed the beanstalk and, with great efforts, arrived in a land high up in the sky, where he followed a road to a house. A house which was the home of a giant. A giant who had many names, such as “local communities”, “groups of interest”, or “people in real life”. Jack entered the house and proposed to organize co-construction and knowledge-building with the giant. But the giant answered:

So, Jack climbed the beanstalk and, with great efforts, arrived in a land high up in the sky, where he followed a road to a house. A house which was the home of a giant. A giant who had many names, such as “local communities”, “groups of interest”, or “people in real life”. Jack entered the house and proposed to organize co-construction and knowledge-building with the giant. But the giant answered:

“Fee-fi-fo-fum!

I smell the blood of a Professor of no help to us.

Be he live, or be he dead,

I’ll grind his bones to make my bread.”

Lack of legitimacy again, but of a different kind: Why the hell would the giant (local communities, people, etc.) accept to work with him, or introduce him to local knowledge? He would do so only if he perceived that Jack had legitimacy enough to represent Giant’s interests and help him have a seat at the decision-making table.

Lack of legitimacy again, but of a different kind: Why the hell would the giant (local communities, people, etc.) accept to work with him, or introduce him to local knowledge? He would do so only if he perceived that Jack had legitimacy enough to represent Giant’s interests and help him have a seat at the decision-making table.

Yes, action research into the streets entails trust. When there is not such trust, professor Jack may very well get side-tracked by biased or incomplete information, or worse be eaten alive.

However, let’s continue the tale: Jack escaped down the beanstalk, with some results plus a bag of gold coins he stole. What do you think happened? Do you think his colleagues recognized his efforts, applauded and joined him to further explore this new field? Nope! They denied any interest in what he had found. Why? Legitimacy, again.

Let me give you an example: Once upon a time, again, in a province of the Netherlands was a research-action study on sustainable planning which results were never published by the authorities who sponsored it. Why? Because (I quote): the researchers who worked on it “had no political mandate for defining sustainable development”. Wow… results were OK, but they were not going to take them into account because they had no right to write what they wrote.

Anyway, back to Jack. Jack was a resilient guy. He didn’t give up. He repeated his journey up the beanstalk and finally found something that convinced his colleagues: A goose which laid golden eggs and a magical harp that played by itself.

Anyway, back to Jack. Jack was a resilient guy. He didn’t give up. He repeated his journey up the beanstalk and finally found something that convinced his colleagues: A goose which laid golden eggs and a magical harp that played by itself.

This time, at least, his colleagues celebrated him. His research became renowned. But they did so under one condition: That Jack chopped the beanstalk down and kill the giant who gave him the goose and the harp. What he did. They were frightened at the idea of the giant breaking into the hushed and consensual atmosphere of their academic club.

Well professors getting out of the ivory box and into the streets … why not? Finally, they thought. But never let “the street” get into our ivory box!

about the writer

Nina-Marie Lister

Nina-Marie Lister is Graduate Program Director and Associate Professor in the School of Urban + Regional Planning at Ryerson University in Toronto.

Nina-Marie Lister

I started my training and career as an ecologist, and later, as an environmental planner. I work today at the intersection of culture and nature in our cities, where landscape, ecology and urbanism mix and mingle. I think of myself as a “pracademic”, with one foot in the academy and another in the practice of making and shaping cities. I have made a career of cultivating the spaces in between disciplines, of jumping fences and building bridges, and of collaboration and transdisciplinary learning. At Ryerson University in Toronto, I founded the Ecological Design Lab as a collaborative community partnership grounded in experiential learning, making and doing. We work to reconnect living landscapes and to build green infrastructure for a more resilient future. In all our work, my students and I lead with landscape.

Why landscape? At the edge of the Anthropocene, at a time when cities are growing faster than ever before in planetary history, landscape is a concept most people understand intuitively rather than technically. Landscapes are real places, grounding us in who we are, where we live. Landscapes are both cultural and natural; they are ecological, social, cultural and spiritual places that brings us together. If we can plan and design our urban landscapes with best available ecological, cultural and economic information, we can invest in a more resilient and sustainable future. If we lead with landscape, we can have hope for nature. As cities are fast becoming the dominant landscapes on the planet, urban nature may soon be the only nature our children will ever know.

As we face unprecedented loss of biological diversity loss coupled and compounded by climate crises, we have an urgent need – and opportunity – to do things differently. Now more than ever, we have a moral imperative and an ethical obligation to plan and design how and where to live differently. This doesn’t mean we don’t need research, or theory and models, but rather it means we ought to use this knowledge differently, in a more direct and applied context, to experiment quickly, rapidly prototype, at scales that are necessarily small, safe-to-fail, in which we co-create with and in our communities.

One way we can re-invest our knowledge and our capital is in nature-based solutions, or in a combination of both natural and designed green infrastructure. We have an abundance of good reliable ecological and engineering data that show clear benefits of ecosystem services of green infrastructure that range of stormwater filtration to biodiversity, to human health and wellbeing. There are ample opportunities to pilot test, implement and study as well as to co-create green infrastructure, especially in tandem with community partners.

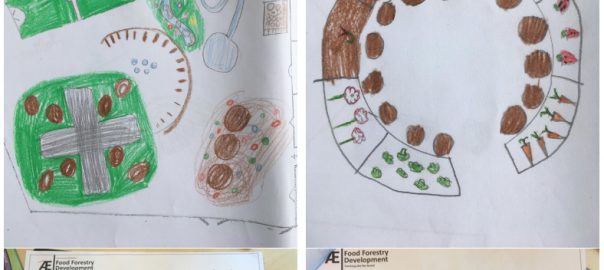

Our work in the Ecological Design Lab is founded on community research-practice partnerships. In our graduate program for example, we train 35 professional planners every year who will plan, design and build cities all over the world. We can and do influence new models of design and planning practice—indeed new communities of practice—from studio classes to field trips and internships. These forums provide hands-on experiential learning as the backbone of co-creation and co-design within communities. This type of “practice-in-place” with our community partners offer context-specific in-situ opportunities for rapid prototyping and deployment of green infrastructure, as well as evaluation and assessment of landscape performance. All this means we can build a growing case for investment in green infrastructure more broadly.

Our work in the Ecological Design Lab is founded on community research-practice partnerships. In our graduate program for example, we train 35 professional planners every year who will plan, design and build cities all over the world. We can and do influence new models of design and planning practice—indeed new communities of practice—from studio classes to field trips and internships. These forums provide hands-on experiential learning as the backbone of co-creation and co-design within communities. This type of “practice-in-place” with our community partners offer context-specific in-situ opportunities for rapid prototyping and deployment of green infrastructure, as well as evaluation and assessment of landscape performance. All this means we can build a growing case for investment in green infrastructure more broadly.

In this context, landscape-based learning is at once possible and critical; landscapes that are designed as social places yet have clear, legible ecological performance are more likely to be valued by those who use them – from parks to trails to wetlands and green roofs. Widespread public adoption of green infrastructure means that people need to appreciate, understand and value—and therefore, care for—these landscapes as more than just recreational or amenity spaces. So it is essential that we make our landscapes and purpose-designed green infrastructure legible, accessible and beautiful! Green infrastructure is multi-functional with many value-added benefits: it ought to be ecologically performative and biodiverse, yet also provide multiple opportunities for recreation, relaxation, and rejuvenation for people. We know that working landscapes, from green roofs to living walls and wildlife crossings can be as beautiful and engaging as they are functional and performative.

In designing the next generation of green infrastructure, our Lab works with community members and professionals alike, engaging them directly in informed best-and next-practices, and together we co-design solutions that work. We use a collaborative hands-on method of working that is familiar to the design disciplines, modelled on a design charrette for the general public and for the allied professionals who work with us. Our ‘CoLabs’ are design and planning workshops—collaboration in practice—through which we develop and co-create site and context specific design solutions in the city. Our students use CoLabs to work on real policies in the city with partners who are our city building agencies. We also partner with not-for-profit groups who can influence decision-makers with examples from other cities, or pilot-test projects and trial demonstrations.

We’ve worked on nature-based solutions for urban flooding, where we focus on re-imagining cities that are structured by their rivers, rather than the conventional strategy of using rivers as urban drains and sewers. In Toronto, the largest post-industrial waterfront in North America is being restructured around a new river mouth for the Don River, and Canada’s largest urbanized watershed. Three levels of government have invested more than $1.5B (Cdn) to develop a new island, a new community for more than 50,000 people with 6 new parks all structured by a new river mouth. For the government, this is a flood protection strategy, but for most citizens, it’s just good place-making and green city building.

The performance values for green infrastructure should be revealed, highlighted and celebrated. Advancing nature-based solutions means communicating the values, services and benefits of landscape-based infrastructure legible and clear. For example, stormwater infiltration is a process of holding, slowing and cleaning storm water to manage quantity and to improve quality. But it must also be about making this process beautiful and accessible to citizens. We can turn gray infrastructure into green infrastructure through projects that celebrate these co-benefits. For example, we can use landscape-based green infrastructure to adaptively reuse and repurpose underused spaces beneath an urban expressway, transforming them into active public places for recreation, water infiltration and biodiversity. Ecological design strategies can be engaged to turn roadside waste places into pollinator pathways, bioswales and green streets. The technical term may be “infiltration basin”, but for most citizens, these are richly planted roadside rain gardens that are accessible, beautiful and legible. If people can understand how these green infrastructures work and the benefits they bring, they are more likely to value the investment and to care for or steward these solutions—nature-based solutions that we know work, and work well.

Green streets do more than just filter and improve storm water. Carefully planted with trees of many species and varied canopies along a gradient of available water and infiltration zones, green streets offer shade while they filter stormwater and sequester carbon. Green streets offer safe bikeways and footpaths, as beautiful places to ride, roll, walk, rest and commune. Although a growing part of the urban public realm, green streets and bioswales do work for more than humans, offering refugia and/or habitat for urban wildlife. For example, urban hydro corridors are being repurposed as combined public spaces, parks, and trail systems for people and wildlife, using different models of vegetation management, including less frequent mowing and stratified planting. In Toronto, the city’s primary hydro corridor is now known as The Meadoway: a 16 kilometer linear park initiated and managed as a public-private collaborative.

The Meadoway and other corridor projects can also include wildlife passages as part of urban natural heritage systems and greenway networks. Increasingly, as our cities stretch into the countryside, our roadways inevitably fragment habitat for wildlife—wildlife that need space to roam, and connected habitats to breed and feed. But roads are also a hazard, as everyone, people and wildlife need safe passage. Green infrastructure also includes adaptively reusing, repurposing or purpose-building passages, tunnels and bridges for wildlife to move safely through our urbanizing landscapes. [

But what about the birds? Green roofs are a nature-based solution in cities that do more than provide public space, improve storm water infiltration and insultation. It turns out they also provide biodiverse pollinator habitat and refuge for migratory birds, acting as “stepping stones” through the city. Toronto was the first city in North America to enact a green roof bylaw requiring a green roof for all new institutional commercial buildings, which has now become a precedent for many cities, including New York and Chicago. With more than 650 green roofs on over 5 million square feet of buildings, Toronto’s green roof bylaw has resulted in a large repository of data on water infiltration, thermal cooling, biodiversity, pollination and heat island effect reduction. Today’s next-generation of green roof infrastructure goes beyond these benefits: we are now building urban farms and prototyping new strategies for urban agriculture. Ryerson University’s rooftop urban farm produces more than 8,000 pounds of fresh produce in only 155 heat degree growing days in Toronto.

These and other nature-based solutions are technical, ecological and engineered infrastructure, yes, but they are also living landscapes that becomes places for people. As social-cultural designs, green infrastructure leverages more benefits and therefore more investment when connected with artists. The Nature of Cities blog and the summit conference is ripe with wonderful examples of artist collaborations that help tell stories about nature in our cities and the infrastructures that sustain them. When artists are involved in these projects, they help make technology legible through story-telling and design. For example, the hydrology of a watershed comes to life as a story of rain to river in this beautiful living “map” at Evergreen Canada, in Toronto.

These and other nature-based solutions are technical, ecological and engineered infrastructure, yes, but they are also living landscapes that becomes places for people. As social-cultural designs, green infrastructure leverages more benefits and therefore more investment when connected with artists. The Nature of Cities blog and the summit conference is ripe with wonderful examples of artist collaborations that help tell stories about nature in our cities and the infrastructures that sustain them. When artists are involved in these projects, they help make technology legible through story-telling and design. For example, the hydrology of a watershed comes to life as a story of rain to river in this beautiful living “map” at Evergreen Canada, in Toronto.

In these projects, we lead with landscape because we know at these small projects add up to big change: they are green links in a living chain, across scales from the site to the city to the region. At scale, they represent a new and urgent shift in investment from grey to green infrastructure. Our urbanizing world needs cities based on nature-based solutions, rooted in the living landscape. Leading with landscape is timely way of rethinking, reaffirming, and redesigning our relationship with nature in the city, and of co-creating and co-producing next-generation practices integrating culture and nature for a resilient future.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation