about the writer

Sarah Charlop-Powers

Sarah Charlop-Powers is the Executive Director of the Natural Areas Conservancy, with a background in land use planning, economics and environmental management.

Introduction

In the United States, four out of five Americans live in cities and urban parks are the nearest and sometimes only place that they have the opportunity to access nature. The Covid pandemic has further highlighted the importance of urban parks and natural areas as a critical form of infrastructure. Parks in cities across the country are currently receiving historic levels of use, as residents seek forms of respite compatible with shelter in place and social distancing guidelines. Natural Areas in particular offer the dual benefits of open space that allows folks to spread out, and access to the beauty and quietude of nature.

Forested natural areas have limited formal protection from city development and stressors and cannot take care of themselves; they need management and continued investment. The protection and management of urban natural areas requires sophisticated approaches as well as long-term planning and investment. Cities across the country and world are facing these challenges. In this roundtable we are introducing work from 12 US cities. These authors and the organizations that they represent are leading efforts to promote and ensure healthy forests in the complex urban environment.

Forested natural areas have limited formal protection from city development and stressors and cannot take care of themselves; they need management and continued investment. The protection and management of urban natural areas requires sophisticated approaches as well as long-term planning and investment. Cities across the country and world are facing these challenges. In this roundtable we are introducing work from 12 US cities. These authors and the organizations that they represent are leading efforts to promote and ensure healthy forests in the complex urban environment.

The Natural Areas Conservancy (NAC) is a non-profit organization devoted to restoring and conserving New York City’s 20,000 acres (8094 hectares) of woodlands and coastal areas. In an effort to strengthen connections with leaders across the United States working in urban natural areas, in October 2019, we hosted a four-day workshop with the goal to strengthen a community of practice, learn from one another and improve management of the places where we work. As a group we discussed and developed case studies on the following topics as they relate to urban forested natural areas:

The Natural Areas Conservancy (NAC) is a non-profit organization devoted to restoring and conserving New York City’s 20,000 acres (8094 hectares) of woodlands and coastal areas. In an effort to strengthen connections with leaders across the United States working in urban natural areas, in October 2019, we hosted a four-day workshop with the goal to strengthen a community of practice, learn from one another and improve management of the places where we work. As a group we discussed and developed case studies on the following topics as they relate to urban forested natural areas:

- Assessment

- Prioritization and Planning

- Climate change Adaptation

- Monitoring

- Innovations in Restoration and Management

- Cross-sector Partnerships

- Organizing and Community Engagement

- Urban Land Preservation and Policy

A special issue of Cities and the Environment was published as a product of this workshop. The issue contains an in-depth explanation of the themes explored in the workshop, as well as 25 case studies written by the city participants describing highlights of the work being carried out to manage forests in cities across the country.

In this roundtable, we are excited to bring this conversation to the Nature of Cities community.

about the writer

Sophie Plitt

Sophie Plitt is National Partnership Manager the the Natural Areas Conservancy. Sophie works to engage national partners in a workshop to improve the management of urban forested natural areas.

about the writer

Clara Pregitzer

Clara Pregitzer is Conservation Scientist at the Natural Areas Conservancy. She led the Forest Assessment component of the Natural Areas Conservancy Ecological Assessment for NYC parkland and the development of the Forest Management Framework.

about the writer

Keith Mars

Keith Mars, AICP, CA, is Community Tree Preservation Division Manager, City of Austin Development Services Department. Keith works for the City of Austin where he manages 35 dedicated public servants that preserve, plan, promote, and study Austin's urban forest.

Austin

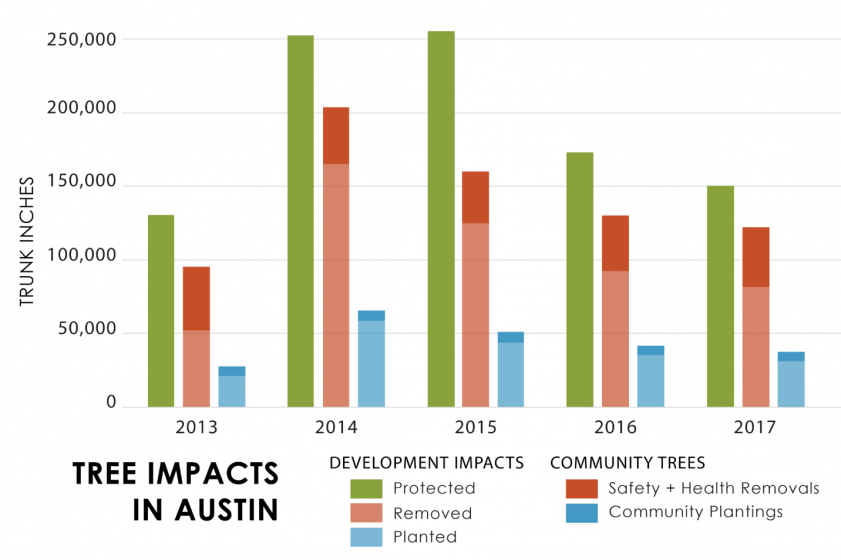

For nearly four decades, our city has enforced tree preservation and replanting ordinances to balance land development with protecting trees and green space that bring so many people to our community (see the figure above). Keeping Austin’s tree canopy intact is important for our community’s quality of life.

Protected trees: Thanks to the City’s tree preservation ordinances, we have protected hundreds of thousands of trees from being removed or damaged during development. Complimentary land use ordinances, such as water quality protection zones and limits on impervious cover, protect intact forested areas.

Tree Removals: Trees are removed every year for a number of reasons, including land development and declining tree health. In 2017, more than 80,000 inches were removed because of development (12 percent decrease from 2016) and almost 42,000 tree inches were removed this year due to declining health (8 percent increase from 2016).

Tree Planting: The City tracks tree planting on development sites and city-sponsored initiatives. Trees planted through the development process totaled more than 30,000 inches in 2017. Tree planting on park property, riparian areas along creeks, rights-of-way, and private property has remained consistent over the past 5 years, averaging 6,600 new tree inches per year (6,400 in 2017). Tree species are chosen for ecosystem function and site suitability, and include large shade, small ornamental, and fruit and nut species.

about the writer

Lydia Scott

Lydia Scott is Director, Chicago Region Trees Initiative. Lydia is the founding Director of the Chicago Region Trees Initiative (CRTI), a regional collaboration of ~200 organizations, founded by The Morton Arboretum.

Chicago

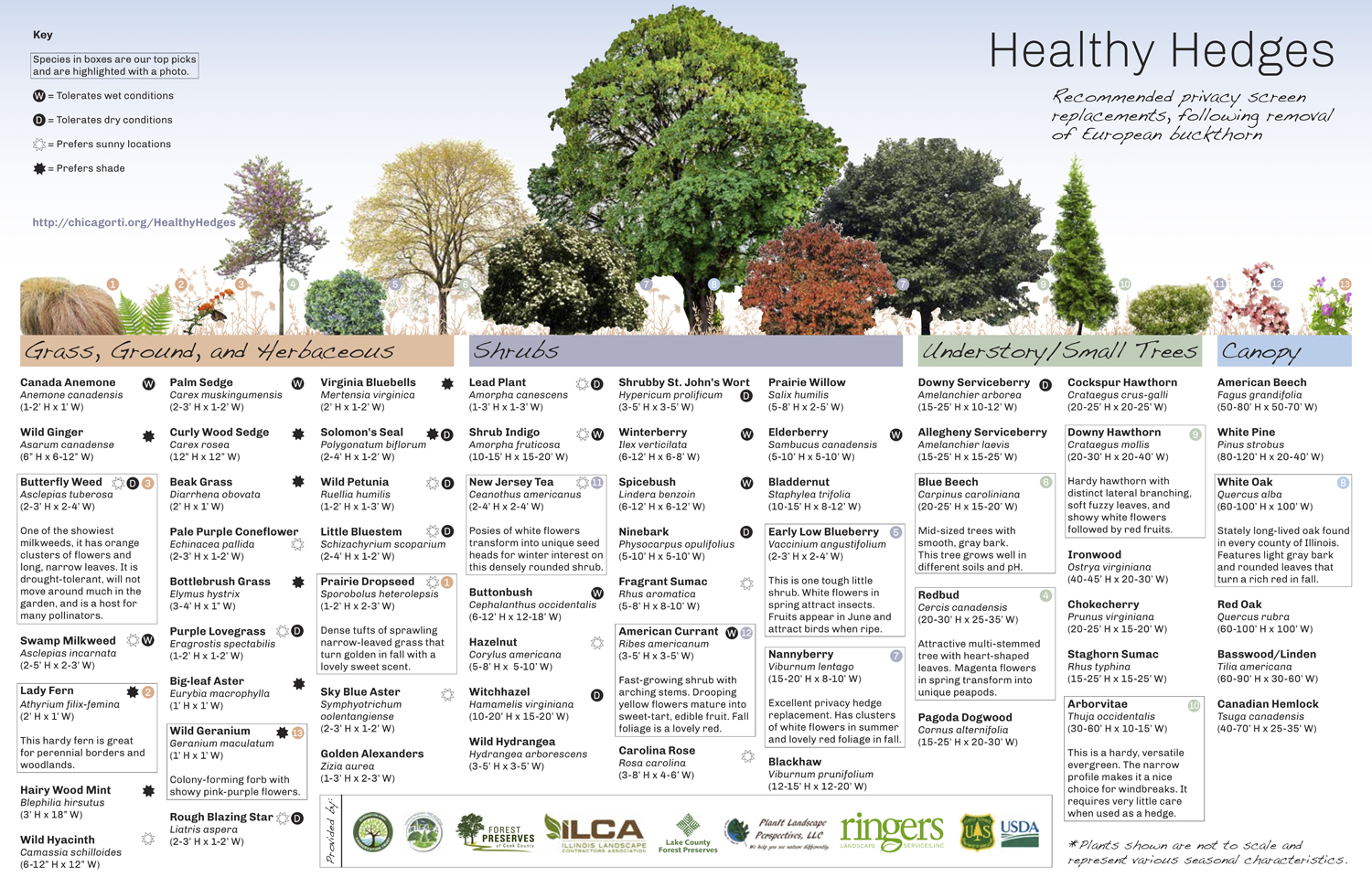

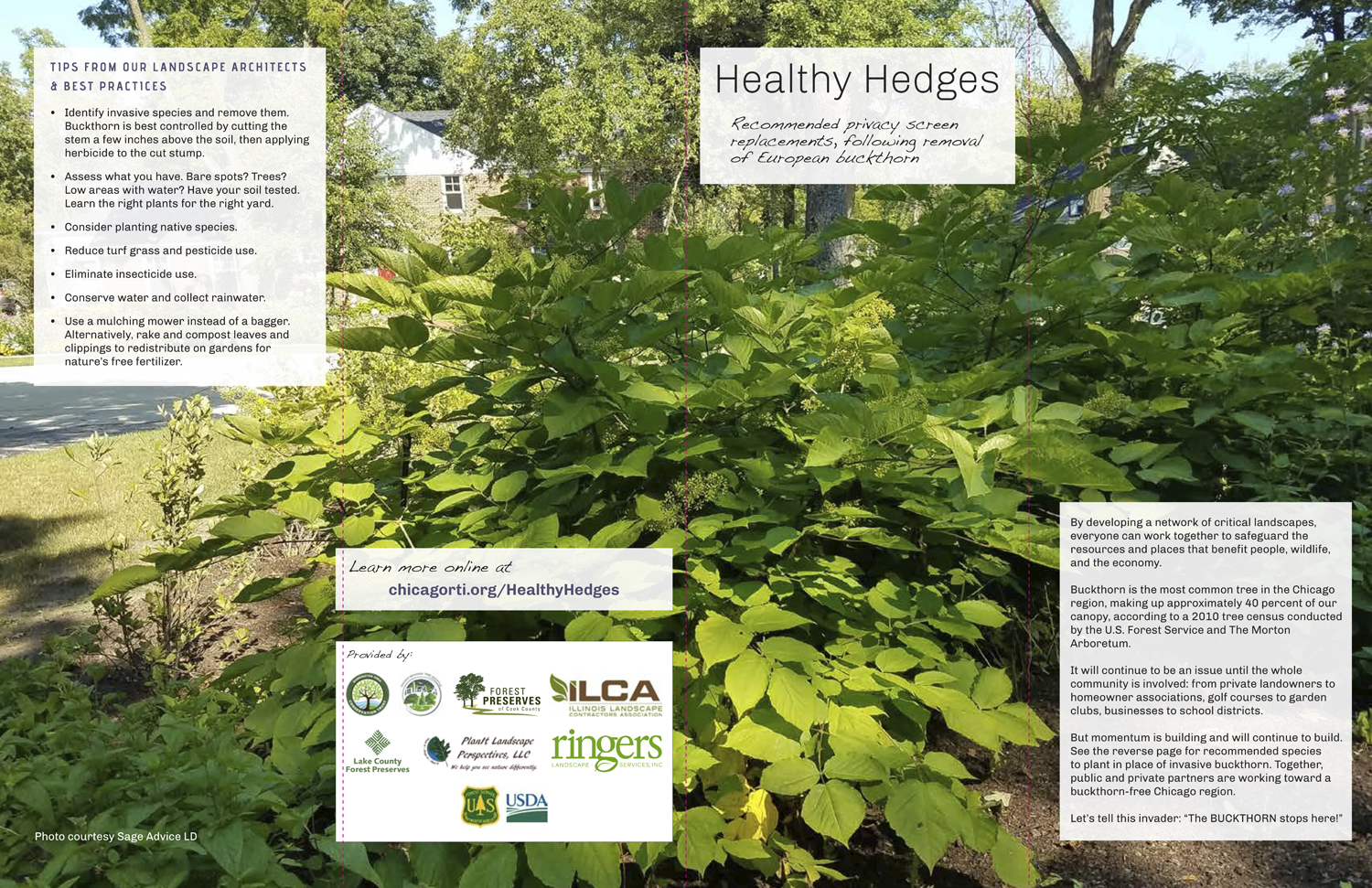

The Chicago Region Trees Initiative (CRTI) has been working with its partners to identify solutions to key issues impacting these oak ecosystems. One that we are currently working on is a collaborative approach to land management to reduce threats. CRTI partners are developing a suite of resources to explain best management practices (BMPs) and make those practices cohesive across land ownerships. These resources are called Healthy Habitats. There are three levels to these resources: Healthy Hedges to eradicate and replace woody invasive species; Healthy Homes to increase planting of native species, reduce use of pesticides and fertilizers, and reduce run off; and Healthy Habitats to explain BMPs that may seem counterintuitive to the general public, e.g. prescribed fire and canopy. The most important aspect of these resources is that they are developed and sponsored by a wide range of partners validating their credibility.

The first effort —Healthy Hedges—is a resource to increase awareness and encourage removal of one of the greatest challenges to our forested natural areas: European buckthorn. Buckthorn is 28 percent of all of the tree species in the region. It creates a monoculture by outcompeting native species and changes the soil composition and chemistry making it challenging or impossible for desirable plant species to grow and inhospitable for some wildlife. For some private landowners, there is a lack of awareness of the existence of this species and its impacts on habitat health. Additionally, for some landowners it is deliberately left in place because it provides a screening buffer for their property. On the flipside, public landowners are well aware of its presence in their landscape and they are spending millions of dollars annually to remove this invasive species only to have it come back as seed is carried from private land to public land by birds.Outreach and collaboration is needed. CRTI partners from the Illinois Landscape Contractors Association, Illinois Green Industry Association, forest preserve districts, mayors and managers, land trusts, community groups, nurseries, and individuals came together to discuss solutions. The result is a series of resources to guide landowners, managers, and individuals to increase awareness of the impacts of buckthorn, tips on how to remove it (including how to stage removal to keep privacy intact), desirable species to plant as replacement, how to work with a contractor (understanding that management of a manicured landscape is very different from a naturalized landscape), and where to find desirable species.

A webinar and in person presentations were sponsored by the Illinois Landscape Contractors Association to more than 400 individual contractors on how to engage their clients to remove buckthorn from their property. The same presentation was taken on the road for counties and followed up by presentations to smaller groups such as garden clubs and environmental groups. A poster was developed with the nurseries that shows alternatives for buckthorn. This poster has been distributed to garden centers and nurseries and a smaller version is being distributed to individuals and landowners to take with them when they shop. Two additional guides were developed with photographs and descriptions of desirable native and non-native shrub species. Finally, an online survey tool was created to help the landowner identify buckthorn on their property, direct them to management strategies, and then help them map their property and “pin” it as “Woody Invasive Free”. Those who achieve this designation are awarded a sticker for their window, mailbox or a property sign.

about the writer

Matthew Freer

Matthew Freer is Assistant Director of Landscape, Chicago Park District. He serves as Assistant Director in the Department of Cultural and Natural Resources, working on the Natural Areas Team.

about the writer

Joseph McCarthy

Joseph McCarthy is Senior Forester, City of Chicago Dept. of Forestry. Since 1990, Joseph has worked to foster cooperation with other city departments ensuring that all reasonable options are explored to preserve and protect city trees in capital improvement projects.

about the writer

Karen Miller

Karen Miller is Executive Planner, Kane County. Karen is leader in the Chicago region on behalf of trees and the environment. She is a certified planner through the American Institute of Certified Planners and is an executive planner with the Kane County Development Department.

about the writer

James Duncan

James Duncan is Environmental Resources Project Supervisor, Miami-Dade County. James is an environmental policy expert and coordinates local wildlife issues for Miami-Dade County.

Miami

Biologically, natural areas in urban Miami-Dade are fragmented, modified through regional drainage, and suffering invasions by non-native species. Currently, less than 3 percent of the upland forest remains. Natural areas in the county are home to seventeen plant and fourteen animal species listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) and well over a hundred more species are listed under similar state and county regulations. Many species are endemic. In 1990, Miami-Dade County voters created the Environmentally Endangered Lands (EEL) Program to acquire, preserve, enhance, restore, conserve and maintain native habitats. The habitats listed consist primarily of globally imperiled pine rockland, hardwood hammock, scrub, freshwater glades, and saltwater wetlands. Additionally, local and federal critical habitat designations have been placed on the vast majority of public and private natural areas in the county.

Outside the national parks, the county’s EEL initiative is the most important public lands project in Miami-Dade. EEL preserves support a diversity of species, outstanding geologic and natural features, and are a sustaining component of our ecosystem. Acquiring, protecting, and restoring these habitats benefits the public. These natural areas protect biodiversity and provide places for the public to see many species. These environmental resources recharge our drinking water aquifer, cool urban heat islands and lessen flooding during heavy rains. EEL preserves are a critical stop-over for the winter bird migration and are key in preventing the extinction of many species. The EEL Program, along with partners, has acquired almost 22,268 acres of land in Miami-Dade County from inception through July 2018. In total, EEL currently manages more than 26,000 acres.

Actions needed to preserve these areas have been developed by different agencies, ranging from the federal Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan to local management agreements. EEL efforts are encompassed in plans for all of these natural areas. Some of these restoration initiatives are starting their fourth decade of progress while others are constantly being modified and created. Aside from management, acquisition today is still a critical need.

Climate change poses new challenges and as the Miami-Dade County landscape changes in unanticipated ways, natural areas are needed more than ever to buffer our population from the most severe impacts. Climate change comes with new management and public land acquisition considerations. Many challenges and needs are easily grasped such as strips of buffer lands to mitigate storm surge and recharge areas to hold water during flood times and provide water during droughts. Other issues are nuanced, such as saltwater intrusion causing direct impacts via lifting a fresh groundwater lens into dry areas and its effect on legacy pollution. Some new dangers are biological. One major challenge to the outlook of urban forested areas is short term risks to forest structure from more resilient invasive vines and increased frequency of wind events.

Aroid vines (primarily Epipremnum pinnatum and Syngonium podophyllum) are sensitive to cold temperatures which historically kept them in check to a degree. These ornamental plants are found the world over in offices and malls, but in South Florida the small leaves and pencil thin vines climb up trees with vines as thick as a wrist and leaves the size of a human. Decreasing die back during the winter combined with tropical storm systems, infested forests have begun to collapse. After Hurricane Irma in 2017, preserve managers reported tornadoes touching down in areas infested with these vines. Tornadoes seemed to be the only way to explain the damage caused by this deadly combination. Control of these vines involve either complicated herbicide application or hiring tree climbers to manually remove resilient vines from the canopy. This challenge is increasingly a priority in many preserves.

In conclusion, what is needed to make our natural areas thrive is mostly known and planned for, and implemented (sometimes slowly). Curveballs like climate change undeniably highlight the need for adaptive management and, at times, reprioritization. Finally, the outlook is hopeful as large restoration projects get implemented and increasing attention to even the smallest natural area provides resources and thoughtful analysis to complex ecosystem problems.

about the writer

Novem Auyeung

Novem Auyeung is a Senior Scientist, Division of Forestry Horticulture & Natural Resources, NYC Parks. Novem guides conservation, research, and monitoring priorities for the Division.

New York

Right: Spring beauty in La Tourette Park. Photo: Desiree Yanes

Of the 10,000 acres, roughly 7,000 are managed by the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation (NYC Parks). NYC was ahead of its time and established the country’s first publicly-funded urban natural resources management unit in 1984. Early work involved conducting inventories and assessments of natural areas on city parkland, which provided valuable information on NYC’s forests (e.g., NYC Parks 1995). This information was incorporated into management plans to improve specific parks and kick-started NYC Parks’ early forest restoration work and monitoring program. In addition, the Forever Wild program was created in 2001 to protect the city’s most ecologically valuable parkland. Thus, from the beginning, data from monitoring and assessments have been used to address the unique challenges of urban forest management in NYC.

When the MillionTreesNYC program was announced in 2007, NYC Parks was able to leverage two decades of forest restoration experience and apply lessons learned at a larger scale than ever before. The program brought together public and private organizations, researchers and practitioners, and professional staff and volunteers to plant one million trees citywide by 2017. This effort was led by NYC Parks and New York Restoration Project and was completed two years ahead of schedule, with over half of the trees planted in forested parkland (Campbell 2017). MillionTreesNYC also strengthened NYC Parks’ volunteer engagement in forested parkland through programs like public planting events (pictured above) and Super Steward training. The success of MillionTreesNYC illustrates the importance of building capacity and awareness for urban conservation through public-private partnerships and community engagement.

In 2012, the Natural Areas Conservancy (NAC), a non-profit organization, was formed and further improves NYC Parks’ capacity to conserve the urban forest. NAC’s kickoff project, a collaboration with NYC Parks and USDA Forest Service, was ecological and social assessments of the city’s natural areas and surrounding parkland. These assessments showed that NYC’s forested parkland is composed primarily of native tree species (Pregitzer et al. 2018) and that natural areas are well-loved and provide nearby nature to many New Yorkers (Auyeung et al. 2016). The assessments also informed the first citywide forest management plan, the Forest Management Framework of New York City, which quantifies the full scope of management actions and costs to improve NYC’s forests—$385 million over 25 years. Thanks largely to New Yorkers for Parks and their Play Fair campaign, the first year of the framework was funded, which enabled NYC Parks to hire new staff dedicated to improving NYC forests and speaks to the importance of planning that is informed by data and supported by diverse constituents.

Nonetheless, NYC’s forests continue to face multiple challenges. Although 85 percent of our mature tree canopy is native, the next generation of native trees and understory flora and fauna are threatened by existing (e.g., mile-a-minute vine) and emerging invasive species (e.g., jumping worms). Forests in the Bronx and Staten Island are under additional stress from herbivory due to the high density of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). NYC’s forests also face problems that affect forests globally like climate change, pests, and development. While the current COVID-19 pandemic has shown that public parks provide a vital service, anticipated budget cuts and decreases in revenue will likely have profound consequences for NYC’s forests and other parkland. What is clear is that continued data-driven management and planning (e.g., King & Auyeung 2020), advocacy and capacity building through public-private partnerships and community engagement (e.g., Forgione 2020, Henderson-Roy et al 2020), and inclusive planning that involves multiple constituents will go a long way towards addressing those challenges to NYC’s forests head on.

about the writer

Lisa Ciecko

Lisa Ciecko is Plant Ecologist, Seattle Parks and Recreation. Lisa works as a Plant Ecologist for Seattle Parks and Recreation, directly managing Green Seattle Partnership restoration efforts.

Seattle

This spring show in the middle of a booming metropolis can be contributed in part to community-powered restoration efforts formalized in 2005 as the Green Seattle Partnership. Our goal is to restore ecological form and function to more than 2,750 acres of forest across 230 parks while galvanizing community stewardship. With Seattle Parks and Recreation as the primary land manager, support from other city departments, non-profit organizations, companies and individuals have built a unique program that is working hard to heal and manage greenspaces long thought to “take care of themselves”. The program model has now been adopted across the Puget Sound Region, with 14 municipalities and 1 county following suit to build Green City Partnerships.

At 15 years old, Green Seattle Partnership is nearing the end of the originally conceptualized 20-Year Plan. This benchmark offers an opportunity to reflect on successes, challenges and next steps. It turns out that 20 years was a bold timeline. Invasive species cover has decreased rapidly, responding to our restoration interventions for the most part and offering a clear signal of success. Sites enrolled early in the program now have maturing conifer trees that optimistically have a lifespan of several hundred years. But even these sites are in the infancy of their renewal. We have lost our “ecological memory”; very basic natural processes like rotting nurse logs and robust wildlife populations are still hard to find in Seattle forests.

Developing and implementing an expanded stewardship timeline is essential to bring Seattle’s forests through the massive environmental and human change expected in this century. Climate change impacts are clearly taking shape in Seattle’s forests. We have to reconcile that the program’s resources don’t always match ecological priorities or timescales. Building understanding of the current program’s status and receiving sustained funding commitments are still our central challenge.

A Green Seattle Partnership bumper sticker reads “Seattle Needs Forests” because the research results are loud and clear that human health and wellbeing depends on the multitude of benefits from nearby nature. The program has succeeded in its original intent to spur community involvement, marking a million volunteer hours invested in the program in 2018. Engagement has expanded to include restoration activities for toddlers to elders. Our leadership and job training opportunities, corporate events, school programming and a robust Forest Steward program are actively building community cohesion. Our challenge moving forward is to push harder to address programming inequities. Again, changing our timescale and perspective before and beyond 20 years may help us reconcile the city’s history of racism that is reflected in its greenspace care, use and distribution of benefits.

Green Seattle Partnership successes and challenges are not just our own. Work with the Natural Area Conservancy during the Forest in Cities Workshop confirmed that cities across the U.S. are facing similar issues. As we continue to tackle the task of shifting approaches, plans and methods to chart a course for what lies beyond the original 20-year horizon, learning from peers nationally is increasingly important. Hopefully the lessons in Seattle will be equally as valuable in restoring and supporting forests elsewhere in the world.

about the writer

Michael Yadrick

Michael Yadrick is Plant Ecologist, Green Seattle Partnership. Michael joined Seattle Parks and Recreation’s Green Seattle Partnership team in 2011. He has also served the land trust community, is a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer (Bolivia ’02-’04) and former AmeriCorps volunteer.

about the writer

Weston Brinkley

Weston is as a policy and research consultant working on the social dimensions of urban natural resources. He currently chairs the City of Seattle's Urban Forestry Commission and holds adjunct teaching positions at Seattle University, the University of Washington, and Antioch University, Seattle.

Very glad to be part of this conversation. I located an excellent paper from here on Baltimore’s urban forest. I grew up there in the densely treed area called Roland Park. I now live in Nairobi where I do not think we have calculated tree cover. Kampala, in next door Uganda, has a tree cover of 13% based on a tree audit. East African cities are increasingly looking at their trees. I see a good piece here on health workers on the front line during COVID in Nairobi. I am happy to link up with others in East Africa on these issues. I have been involved with the restoration of Michuki Park and also the greening of the Gachie-Waiyaki way bypass.