As the virus and the revolution continue to unfold in real time, all with the threat of climate change looming, we must ask ourselves who and what we will prioritize. Will we continue to feed the systems that claim to keep us safe, while in reality upholding white supremacy at the cost of Black lives? Or will we invest in our community resources in the places where it counts the most?

Despite some of the rhetoric circulating, we know that COVID-19 is not a great equalizer that is blind to color and privilege. It is true that this pandemic is personally impacting every individual in a way that few events in history have, and that the COVID-19 infectious droplets cannot themselves discriminate based on race or class. But just as “natural” disasters are a result of both social and environmental factors, the virus itself is only one actor in the current pandemic. Our leaders, police, and healthcare systems are all co-producers of this crisis and help dictate who is impacted. Environmental justice literature and activism have taught us that the effects of climate change disproportionately burden the already vulnerable, and COVID-19 is no different. We are seeing increasing evidence of disturbingly high death rates in poor Black communities in the United States, while the wealthy can escape to their private islands to wait out the pandemic in luxury.

This means that open spaces in urban areas are needed now more than ever. Those of us with the privilege to have a public park within walking distance have likely seen a change in how the space is used and what it means to us. A few of my colleagues and I have been journaling about our experiences in New York City during shelter-in-place, and all of us have found new meaning in our neighborhood walks and park visits. Beyond providing crucial ecosystem services, parks allow for physical fitness and recreation, and have proven mental health benefits. As the weather warms, parks and open spaces are becoming even more of a necessity, providing places to visit with friends while maintaining safe social distance.

But we also know that access to and safety within public space is an issue of racial equity that has been heightened since the pandemic. Activists have long been aware of the general lack of parks and public space access in lower income communities of color. It is no surprise that these few existing parks are seeing increased crowds on nice days, nor is it surprising that we are seeing disparate enforcement of social distancing. Images of police happily handing out masks in crowds of white people contrast sharply with the violent, stop-and-frisk style policing in Black neighborhoods. This inequitable policing, along with the surge in the murders of Black bodies, reminds us that there are multiple pandemics going on right now, all of which are disproportionately impacting the Black community.

The recent public murders of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery—the latter of which has been charged as a hate crime—along with the racist incident against Christian Cooper in New York’s Central Park (which could have easily also ended in police violence), are all direct results of the racist police system embedded in the origins of our country. Indeed, the case of Arbery arguably fits the definition of a “lynching,” an informal public execution over an alleged offense without legal trial. In addition, all of these incidents took place in public spaces that belong to the victims just as much as they belong to anyone else. These are just a few of the recent examples of a much more pervasive and systemic problem, a problem that protesters on the streets demand be finally solved.

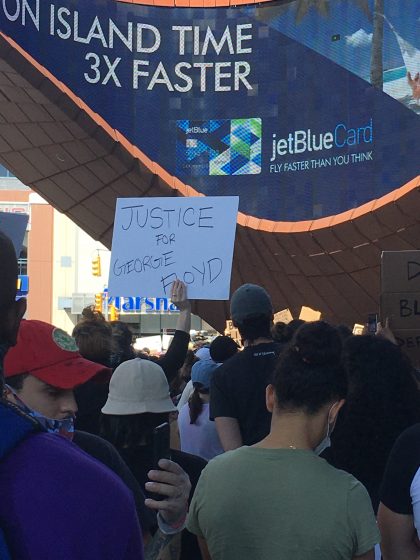

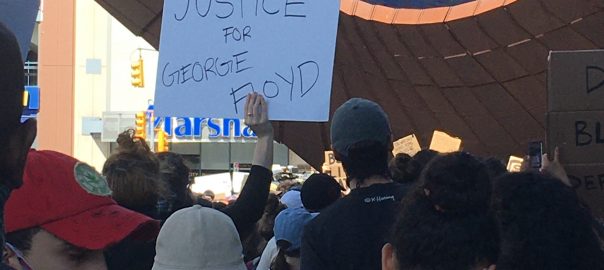

These protests have highlighted another important use of public space: the right to assemble. Following Trump’s election, New Yorkers for Parks documented the hundreds of thousands of people who came out to protest in NYC public spaces in the year 2017. The streets, parks, and plazas served a crucial role as gathering points for demonstration. Now, many of those same spaces are once again being activated. In my own Brooklyn neighborhood, I’ve joined and witnessed crowds filling major streets like Eastern Parkway, and congregating at Barclay’s Center and Grand Army Plaza. I am reminded of the many times I have gathered with my community in those spaces to pray, to celebrate, to mourn, and to speak out. I am reminded that the ability to take up space in public is a human right that is protected for white and privileged citizens but not others.

In the past few days, Mayor Bill deBlasio has condemned the “violence” of protesters against inanimate objects while defending the police for driving an SUV into a crowd of people, threatening human lives (he only softened his stance after considerable blowback). Recent budget cuts to crucial city agencies—including the Parks Department have affirmed deBlasio’s priorities. He thinks that more police will equal more safety. But we know that it is the eyes on the street of our community members that keep us safe, not the police. Luckily, some of our leaders agree, and are pushing back against deBlasio’s budget proposal. In an email to his constituents on 31 May 2020, New York City Council Member Brad Lander called for a de-escalation of the NYPD:

“At the city level, cuts to the NYPD’s budget are necessary. As the city faces a massive deficit, the mayor proposed a budget that would put a hiring freeze on teachers, counselors, youth workers, parks workers … but not police officers. If we can’t afford to hire more teachers, then we cannot afford to hire more cops.”

—New York City Council Member Brad Lander

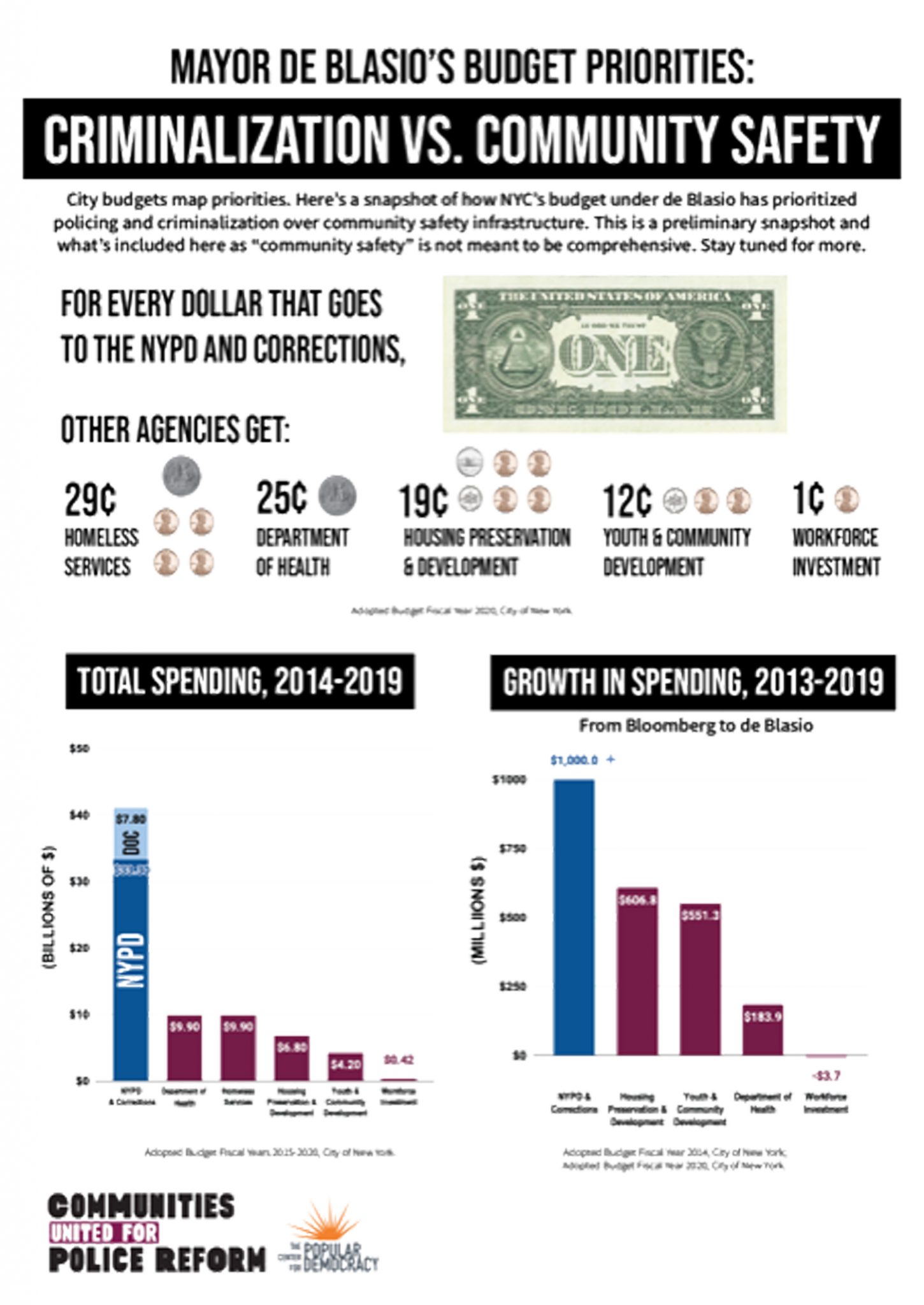

Lander also highlighted the work of Communities United for Police Reform (CPR) in leading a campaign for budget justice (#NYCBudgetJustice). As it stands, for every dollar toward the NYPD, crucial agencies and services are getting pennies (see image). The campaign calls for cuts to the nearly $6 billion NYPD budget, and for funds to be redirected towards social services that work to combat the impacts of COVID-19, particularly in the Black, Latinx, and other communities of color that have been hit the hardest. Imagine the impact $6 billion could have on our communities if it instead went toward public health, fair and affordable housing, community programing, and parks.

As the virus and the revolution continue to unfold in real time, all with the threat of climate change looming, we must ask ourselves who and what we will prioritize. Will we continue to feed the systems that claim to keep us safe, while in reality upholding white supremacy at the cost of Black lives? Or will we invest in our community resources in the places where it counts the most? We have entered a moment of sustained uncertainty, and many are feeling the hopelessness that comes from not knowing what will come next. Instead of giving into despair, let’s address the things we can control, starting with starting with reallocating money away from police departments and toward the services and public spaces that foster community building.Audre Lorde reminds us that “Sometimes we are blessed with being able to choose the time, and the arena, and the manner of our revolution, but more usually we must do battle where we are standing.” As researchers and practitioners who are passionate about sustainable and just cities, this is our fight.

Laura Landau

New York

Leave a Reply