More people are changing how they use green and open spaces in New York during COVID-19, but we found the perception of access to these spaces remains unequal, and reduction in funding further compromises the ability of parks managers and city officials to manage these significant shifts in use.

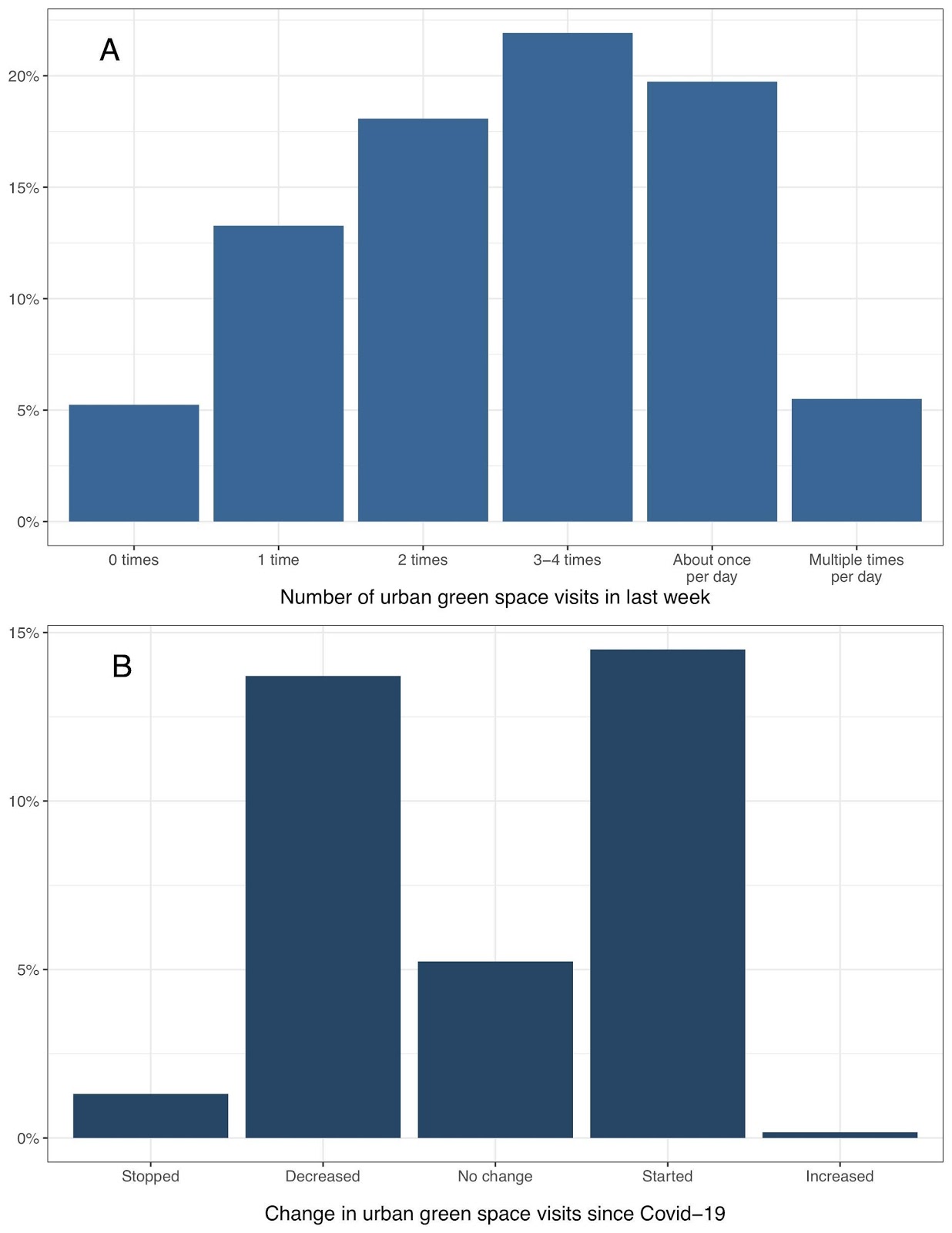

In cities like New York, which was hard-hit by the impacts of the pandemic early on, reports of increased park use in some areas signaled a radical shift in mobility and demand for services as communities across the region adapted to new social distancing policies and mandates. With some parks and natural areas closed, while others partially restricted, the Urban Systems Lab in collaboration with The Nature Conservancy in New York,Building Healthy Communities NYC, and the New York State Health Foundation launched a social survey from 13 May to 15 June 2020 to better understand the shifts in use, importance, and perceived access to urban green spaces across the five boroughs. Our aim was to capture a snapshot during a critical time period following some of the worst health impacts in the City, but, before New York State entered into Phase 3 and 4, when restaurants and businesses partially reopened. In total, we received 1,372 responses to a NYC survey, and 1,145 people completed over 70 percent of the survey questions used for analysis.

The results of the survey show New Yorkers continued to use urban green and open spaces during the pandemic and considered them to be more important for mental and physical health than before the pandemic began. However, the study revealed a pattern of concerns residents have about perceived accessibility and safety, and found key differences between the needs of different populations, suggesting a crucial role for inclusive decision-making and urban ecosystem governance that reflect the differential values of communities across the City. More than this, the study highlights an urgent need for additional funding, and consistent and practical guidelines to meet shifting demands, and to ensure the safe implementation of adaptive management strategies. In this post, we highlight some of the findings from the study and discuss the crucial role urban green spaces play during extreme events. We advocate for recognition of parks and open spaces as more than an essential service, but rather a critical urban infrastructure that provides multiple benefits and ecosystem services to address the interdependent impacts of the COVID-19 health crisis as well as other threats posed by climate change and socio-economic instability. Throughout we take an inclusive approach to the term urban green space, which we refer to as any public spaces with natural or managed vegetation, including parks, greenways, public gardens, plazas, and accessible wetlands, forests, prairies, and beaches.

Spaces of refuge for physical and mental health

Urban green spaces provide a host of mental and physical health benefits. Multiple studies indicate how they promote and increase physical activity, improve air quality, and decrease respiratory illness, in addition to improving general mental health, and reducing stress and mental disorders. Others point to urban green and open spaces as a way to relieve the chronic stress of cramped spaces and housing, with perceived importance directly related to community quality and cohesion. This is especially true for communities living in dense urban areas.

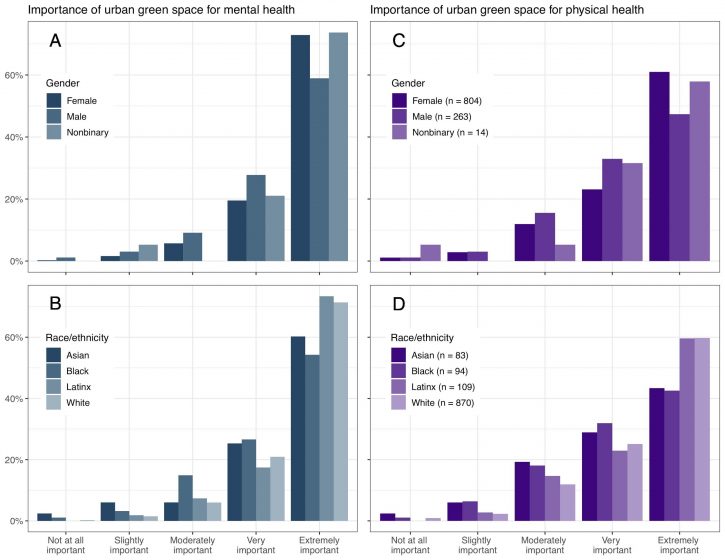

In our analysis, we found that most respondents considered urban green spaces to be very or extremely important for their health (88% for mental health, 80% for physical health) and that this held true for all groups across gender, race/ethnicity, and borough. While scholars and practitioners have known this for some time, the multiple and interdependent impacts of the pandemic have brought new meaning to the idea of urban green spaces as a sanctuary or space of psychic refuge. What we found particularly interesting in the results of our study is that respondents generally considered urban green spaces to be more important for mental than physical health. This may indicate the many different roles that urban green spaces can provide for communities especially as a documented case of ongoing “COVID depression” spreads nationwide and social isolation creates additional barriers to the kinds of cohesion and community-building needed for overall well-being. Urban green spaces in this sense may be critical for alleviating mental stress and health, and point to the necessity of providing continued access to these spaces during times of crisis to prevent further inequities in public health.

Uneven access, unequal service

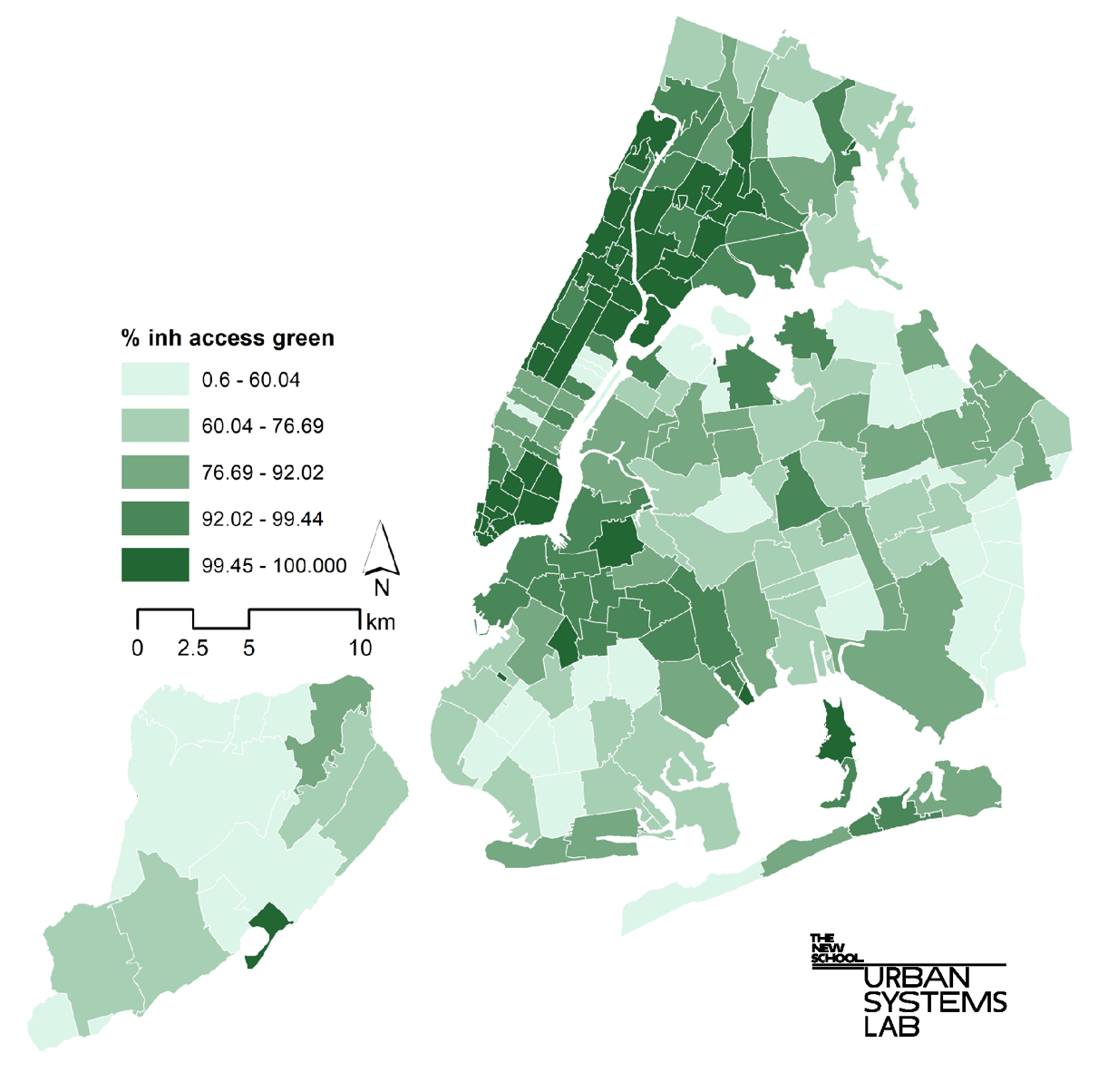

Do all New Yorkers have safe and easy access to an urban green space? Yes and no. According to the Trust for Public Land (TPL), nearly all New Yorkers live within a 10-minute walk to a green space. While this may appear equitable, higher rates of White residents tend to live near large parks with a greater level of desired features. This is now a national trend confirmed most recently in a TPL study published earlier this year. In contrast, low-income and communities of color are more likely to lack access to green spaces of quality and to face disinvestment in local parks, which often do not include basic amenities like bathrooms or basketball courts. Even without considering the multiple impacts of the current health crisis, access to parks and open spaces of quality are not equal for New York’s diverse communities.

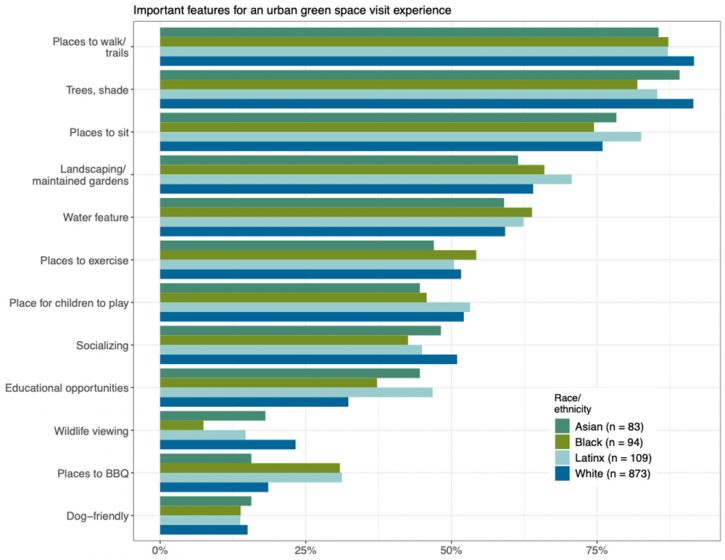

However, the question of access is not necessarily the whole story. The use of urban green space depends on more than just who is within physical proximity to parks, but what amenities those spaces provide, how well they match the needs of the community, and who feels safe and welcome to use the park. In a Citywide Social Assessment conducted by NYC Parks and USDA Forest Service in 2014, researchers showed that park visitation correlates with park size, facilities, and the ability to participate in recreational activities and engage with the local environment. And, in a study analyzing NYC park usage through social media data, researchers found the key determinants of visitation are linked to park facilities, access to public transportation, the size of the park, and socio-demographics of the neighborhood.

In our study, we were interested in questions of accessibility, but also understanding resident’s “perceived access”, or ease with which people can reach desired urban parks or open space sites. And similarly, if new concerns over safety, overcrowding, or a lack of desired amenities would influence this. Overall, we found these additional concerns have made an impact, with perceived access to parks unequally distributed across the 5 boroughs, although relatively high because of the number of parks and open spaces in the City.

Approximately 75 percent of respondents said that they had “safe and easy access” to an urban green space, with access to “natural areas” significantly lower, ranging from 53 percent in Staten Island to 20 percent in Brooklyn. In our initial spatial analysis, however, we found that residents in Queens and Brooklyn have lower perceived park access, as well as receive less of their desired features from urban green spaces. This is particularly concerning as studies point to neighborhoods in Queens as disproportionately impacted by COVID-19, which are also at higher risk and incidence to conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, exposure to extreme heat, poor air quality, and heart failure. These have been identified as comorbidities that significantly increase the likelihood of patients requiring hospitalization, contribute to COVID-19 fatality, which may be exacerbated by a reduction in perceived access to produce further inequities.

New concerns, shifting needs

As many recent reports suggest, the increased use of urban green spaces is taking a toll on the maintenance and capacity of parks to meet the evolving needs of users. In our study, even though visitation to urban green spaces increased for some during the pandemic, we found that shifting needs of New Yorkers can also result in a decrease in park visits. While more than half of park users surveyed were concerned about issues of safety, the concerns and emerging needs also varied across locations and social groups. For example, in selected write-in comments, some Black-identifying respondents expressed concern about police presence in parks or racial profiling, while Latinx respondents more frequently selected “lack of park staff.” One survey respondent explained: “Feels like parks for white people these days and law enforcement continue to target people of color.”

Parks with desired features are key as well. Our findings indicate that people may not use the park or open space closest to them if it does not have the desired amenities or if it is too small and likely more crowded. While the majority of respondents indicated landscaping and trees, places to sit and walk, and water features as a high priority, other communities placed a different value on park features such as places to socialize and cook food within parks, wildlife habitat, or educational opportunities. Additional write-in comments also suggest that other features were necessary, such as public restrooms and open playgrounds. These results highlight the ways in which residents’ beliefs and attitudes are not necessarily uniform and an urgent need to increase the capacity of NYC Parks and other agencies to better understand shifting behaviors and to include communities authentically in decision-making processes.

Moving Forward: Parks as Critical Urban Infrastructure

So, what are city officials and planners to do, especially in light of recent budget cuts and the likelihood of the pandemic extending into the coming year? How do we plan for equity and resilience?

Although the severity of the COVID-19 crisis this Spring was unprecedented, many of our partners point out that there are still no clear guidelines for how to translate the New York State Department of Health or recommendations from experts into practical measures for NYC’s park and open space managers. The lack of consistent messaging and guidance earlier this Spring meant that some playgrounds were required to close with reports of others remaining open, certain natural areas were closed while others remained accessible, and open spaces not maintained by NYC Parks had to determine policies in an ad hoc fashion. This absence of responsive and inclusive policies, especially in times of crisis, tend to disadvantage low-income communities, while reduced funding compromises the capacity of NYC Parks, park conservancies, and other City agencies to adequately respond and adapt.

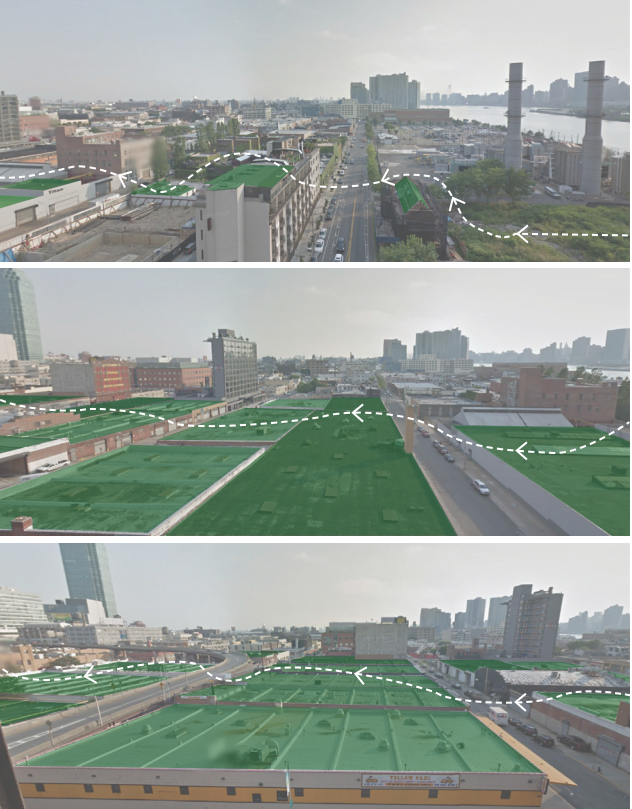

Long-term, planners may need to think differently about how urban green spaces are supported both financially and also through engagements with the communities who use and benefit from these spaces. This requires thinking critically about parks and open spaces not just as isolated islands of ‘Nature,’ but rather as complex urban ecological networks that operate as multifunctional systems, providing ecosystem services, transportation opportunities, flood and extreme heat protection, and support local and regional economic activity. Urban green spaces in this sense are more than essential, but rather critical urban infrastructure to manage the multiple impacts of COVID-19 as well as other threats.

In New York City, linking smaller parks with larger parks, NYCHA open spaces, waterfront hubs, community gardens, open and cool streets, and natural areas through a network of urban ecological infrastructure could begin to address issues of uneven perceived access and additional safety concerns reflected in the results of our survey. As many respondents noted, urban green spaces are often fragmented and the spaces with desired amenities can be difficult to access with many traveling greater distances, adjusting their typical routines, or actually reducing or stopping their park use altogether. This suggests that access to urban green space is not necessarily about proximity to a park or open space, but rather a perception of having safe and easy access to an urban green space that meets user’s needs.

This is especially crucial in considering the interdependent and cascading risks of extreme events such as heatwaves and coastal storms, and how they may interact with COVID-19. A reduction in staffing at NYC Parks for instance already had major impacts on City services in the aftermath of Tropical Storm Isaias which caused more than 800,000 people to lose power in New York State in August 2020. Due in part to staffing shortfalls within NYC Parks, the cleanup and recovery were significantly delayed, placing those with pre-existing vulnerabilities at greater risk. Given the likelihood of these events reoccurring with an increased intensity quite high, planning for and building resilience is key.

As parks and open spaces increasingly emerge as a “pandemic commons,” this new appreciation is not just a challenge to manage or merely a strain on resources, but also an opportunity to rethink the role parks and open spaces play in our daily experience. And, more importantly, a call to action to ensure all New Yorkers have a say in the future operations of urban parks and open spaces.

Timon McPhearson, Christopher Kennedy, Bianca Lopez and Emily Maxwell

New York

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted by the Urban Systems Lab at The New School in partnership with The Nature Conservancy in New York and Building Healthy Communities NYC. Funding for the study is provided in part by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number (2029918) and the New York State Health Foundation. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

about the writer

Christopher Kennedy

Christopher Kennedy is the associate director at the Urban Systems Lab (The New School) and lecturer in the Parsons School of Design. Kennedy’s research focuses on understanding the socio-ecological benefits of spontaneous urban plant communities in NYC, and the role of civic engagement in developing new approaches to environmental stewardship and nature-based resilience.

about the writer

Bianca Lopez

Bianca Lopez is a postdoc at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the Northeast Climate Science Center working at the intersection of invasion ecology and climate change to inform land management. She has also collaborated with social scientists to study people’s interactions with nature and is interested in art as a way to communicate science and inspire conservation behavior.

about the writer

Emily Maxwell

Emily Nobel Maxwell is dedicated to environmental justice and urban greening. She is Director of The Nature Conservancy’s NYC Program and Advisor to TNC’s North America Cities Network.

Leave a Reply