1 We are part of nature

We are part of nature and we are interdependent with nature.

We are part of nature and we are interdependent with nature.

2 We think we can be separate from nature

We cannot escape this interdependency. Even when we try, we are tied to living systems by umbilical cords of technology, constrained by natural limits.

We cannot escape this interdependency. Even when we try, we are tied to living systems by umbilical cords of technology, constrained by natural limits.

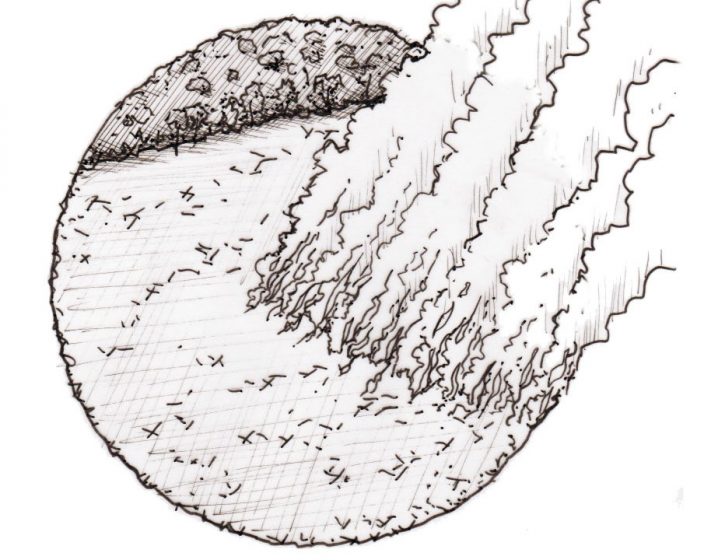

3 Human culture is a force of nature

Our culture is manifest in our actions. Everything we do affects the natural world in some way. We are a force of nature.

Our culture is manifest in our actions. Everything we do affects the natural world in some way. We are a force of nature.

In his slim but vital tome published in 2004, Stephen Boyden wrote from a “biohistorical” standpoint about human culture as a force of nature in The Biology of Civilisation and his main conclusion was that “biounderstanding is key to sustaining civilisation and ecological health and the dominant culture must ‘embrace, at its heart, a basic understanding of, and reverence for, nature and the processes of life.”

There are few reasons to be optimistic about the prospects for biounderstanding becoming central to culture, but the need for it is inarguable.

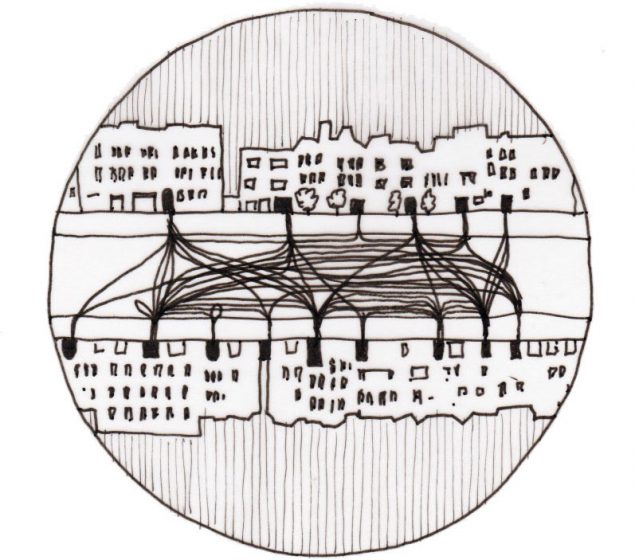

4 Patterns of action

Everything we do is part of the patterns that make up our lives. Patterns of action reflect culture. The graphic is based on the seminal studies by Appleyard which captured the patterns of community and communication in a street and how it was affected by vehicle traffic.

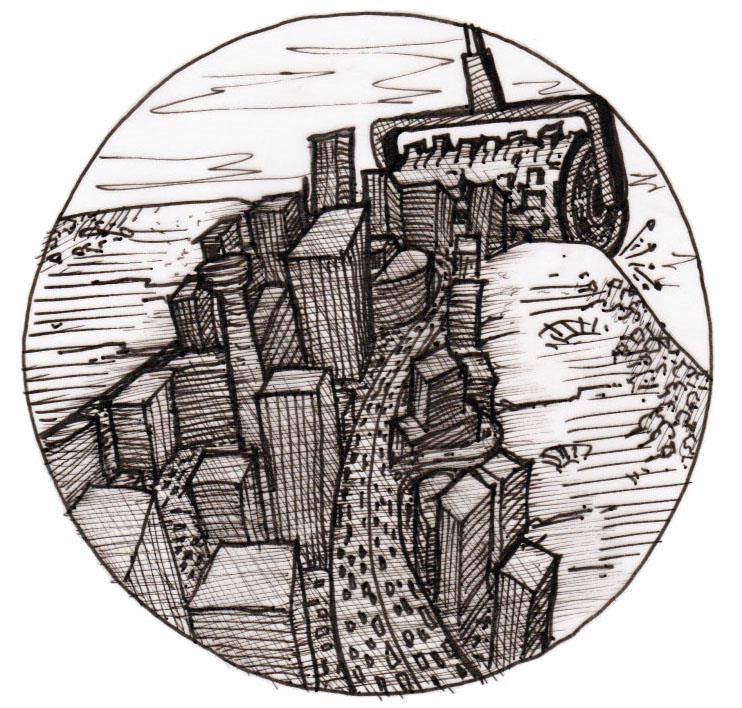

5 Culture and power

The dominant culture is determined by power relationships. Patterns of living are part of the patterns of occupying and using space. They are part of how we form our human habitats within the bubble of the biosphere.

The dominant culture is determined by power relationships. Patterns of living are part of the patterns of occupying and using space. They are part of how we form our human habitats within the bubble of the biosphere.

How we build affects the natural world.

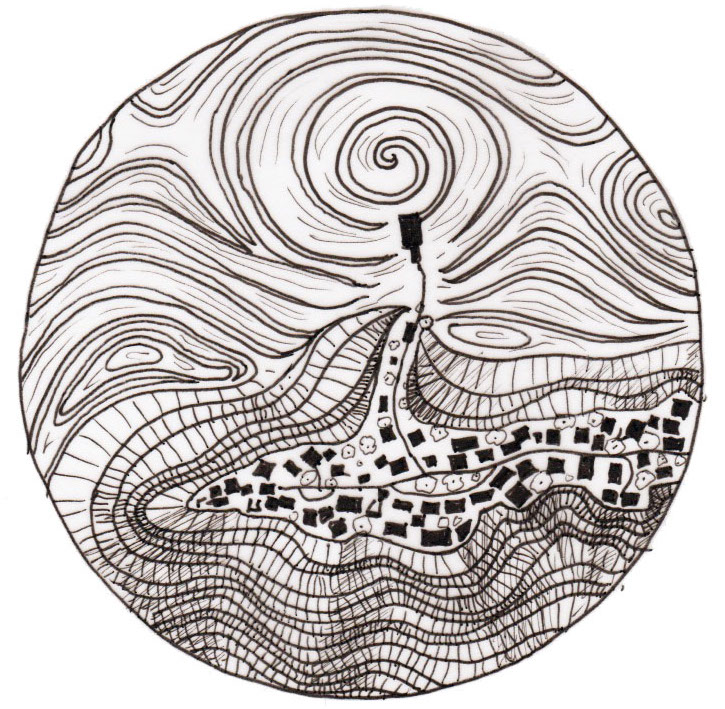

6 Patterns that remain

Like vortices in the stream of biohistory, our constructed habitats are human patterns that remain. In “Steps to an ecology of mind” (1979), Gregory Bateson identified patterns as key to understanding the relationship between humans, culture, and nature and wrote of the “pattern that connects”.

Like vortices in the stream of biohistory, our constructed habitats are human patterns that remain. In “Steps to an ecology of mind” (1979), Gregory Bateson identified patterns as key to understanding the relationship between humans, culture, and nature and wrote of the “pattern that connects”.

One result of those patterns is human habitation in its relationship to the biosphere as mapped by villages, towns, and cities.

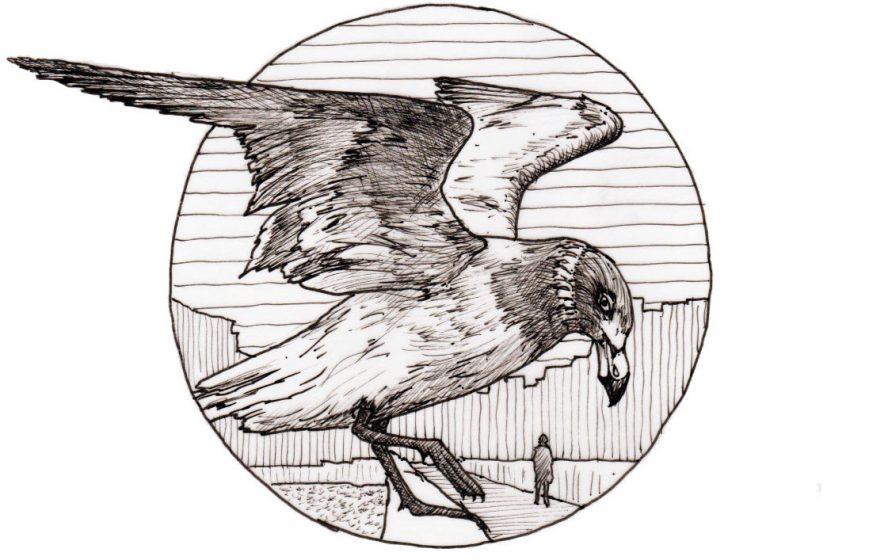

7 Nature needs social distancing too!

To enable nature to recover from the severe impacts of human exploitation on the patterns of nature, from habitat loss to plastic pollution, climate change, and everything in between, we have no choice but to change how we build. Which means changing our patterns of behaviour.

To enable nature to recover from the severe impacts of human exploitation on the patterns of nature, from habitat loss to plastic pollution, climate change, and everything in between, we have no choice but to change how we build. Which means changing our patterns of behaviour.

We are implementing behavioural change to tackle the spread of COVID-19 because our lives depend on it. We must do it to rescue the biosphere from collapse because our lives depend on it.

Nature needs “social distancing” too.

8 The big picture is ugly

The big picture isn’t looking good. But the patterns for real change come from below, from daily life changes at a local level.

The big picture isn’t looking good. But the patterns for real change come from below, from daily life changes at a local level.

9 Despair

We can’t afford to despair. Lives depend on it. All lives.

We can’t afford to despair. Lives depend on it. All lives.

10 Everything is fractal

Everything we do is fractal. It is all part of a larger pattern. It is the larger pattern writ small.

Everything we do is fractal. It is all part of a larger pattern. It is the larger pattern writ small.

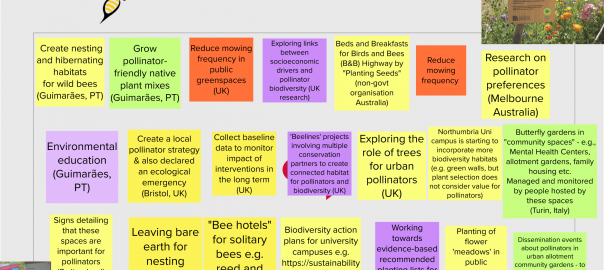

11 Design guidelines for non-human species

In my first TNOC blog, building on my doctoral thesis from 20 years ago, I argued that the creation of ecological cities requires the development of Design Guidelines for Non-Human Species. I suggested that an urban fractal or neighbourhood should be able to provide sufficient viable habitat that could support at least one key indicator species of fauna and a majority of the species of birds indigenous to the place. Later, I tried to take that idea further; it was supposed to be about changing the culture, deeply, it was supposed to be about something that is exciting, challenging, and worthwhile.

In my first TNOC blog, building on my doctoral thesis from 20 years ago, I argued that the creation of ecological cities requires the development of Design Guidelines for Non-Human Species. I suggested that an urban fractal or neighbourhood should be able to provide sufficient viable habitat that could support at least one key indicator species of fauna and a majority of the species of birds indigenous to the place. Later, I tried to take that idea further; it was supposed to be about changing the culture, deeply, it was supposed to be about something that is exciting, challenging, and worthwhile.

But it still turned into a somewhat uninspiring list.

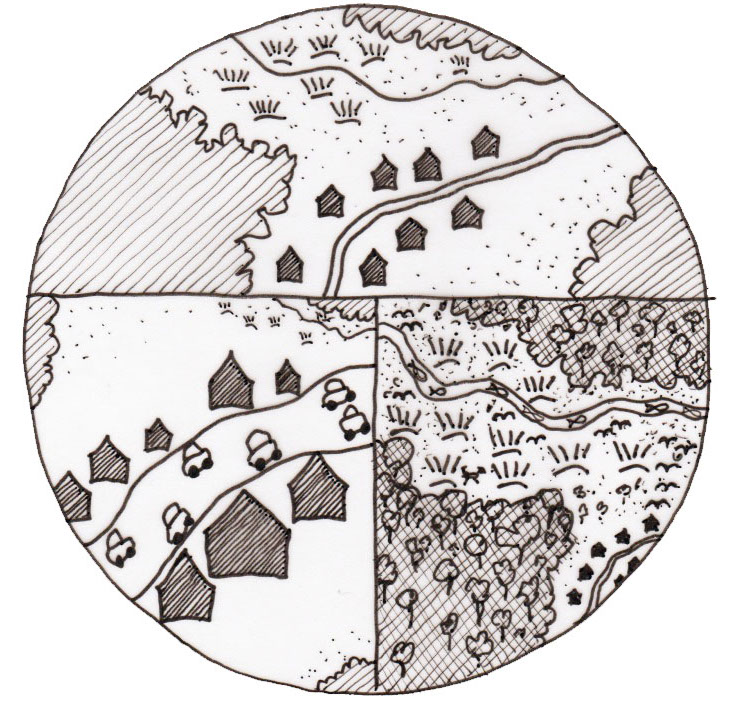

12 Points of view

The design guidelines spoke to responsible planners and change-makers but, whatever its merits, I am compelled to observe that they really aren’t the sort of thing that stirs the blood and, more importantly, they don’t paint the bigger picture – to see how the patterns connect you have to actively make the connections. You have to see and experience the patterns.

Fractals are about pattern, not lists, but to see that bigger picture more clearly we have to speak with science, poetry, and art.

It’s about culture, after all.

The above graphic shows three points of view. The top one is the nominally objective “normal” as described by human mapping, the left one is “mainstream” culture with a consciousness of the car and house dominating all other reality. The right part of the image suggests how it might be seen from nature’s point of view.

There is some movement towards looking at the city from a non-human point of view see, for instance, Urban Animals: Crowding in Zoocities, reviewed by Chris Hensley in TNOC in 2015 in which Hensley notes that “using a nonhuman-centered framework, it sheds light on issues from a very different angle than that from which we are used to approaching such subjects” and that “the animal-focused framework presented here will be crucial in understanding urban life of the present and future.”

But patterns must be key.

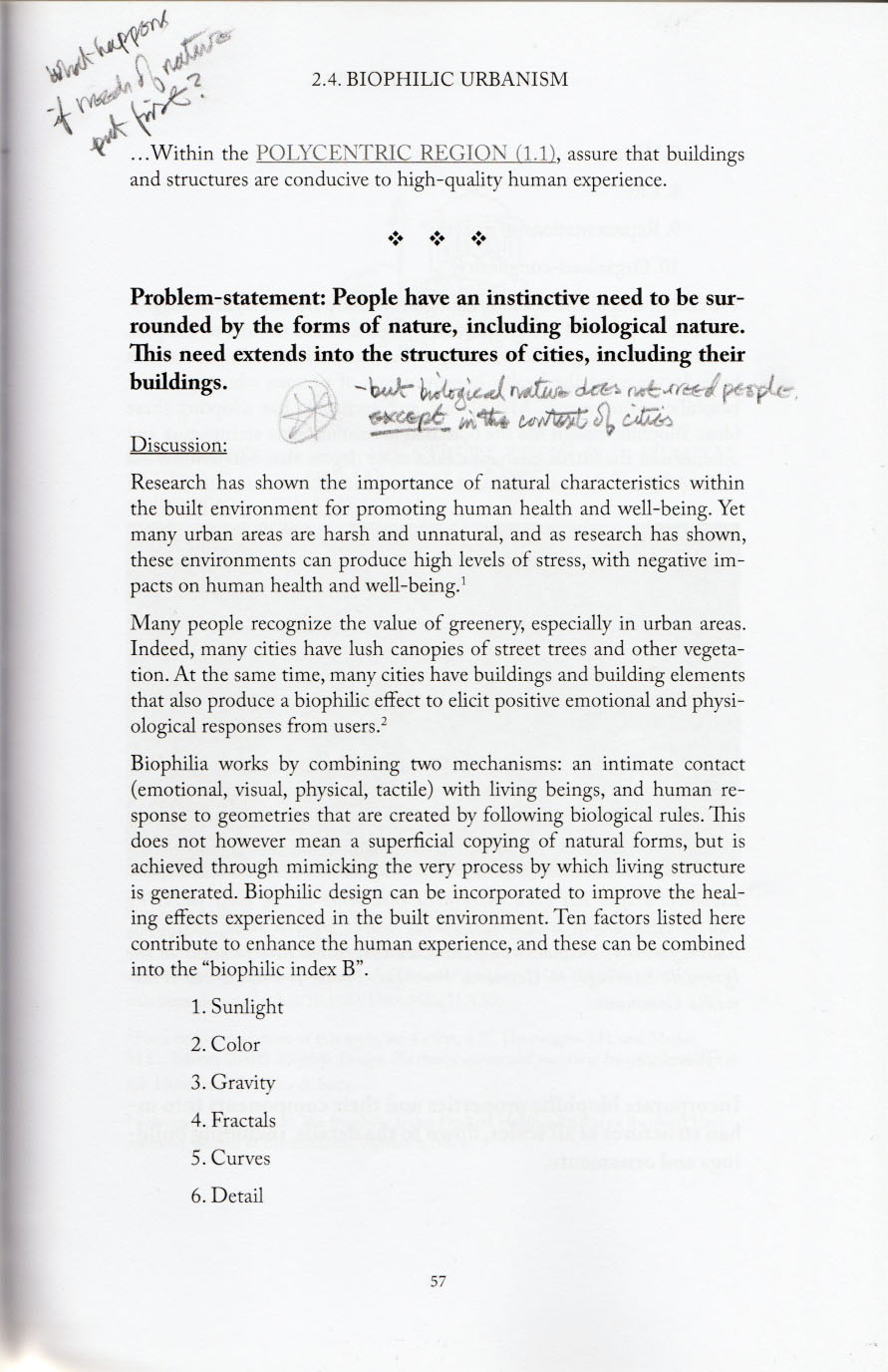

13 A Pattern Language for Urban Nature

Taking my cue from Alexander et al and Mehafy, Salingaros et al, I am becoming convinced that there may be a way to bring these ideas to life in a way that has the potential to connect with the daily life of humans and other species. The proposition is simple: What happens if we take a pattern language approach that puts nature first?

Taking my cue from Alexander et al and Mehafy, Salingaros et al, I am becoming convinced that there may be a way to bring these ideas to life in a way that has the potential to connect with the daily life of humans and other species. The proposition is simple: What happens if we take a pattern language approach that puts nature first?

I don’t have the resources to take this line of thinking a lot further, much as I would like to, so this graphic essay is little more than an indicator of what may be possible as something that might be developed in a similar fashion to and complementary to “A new pattern language” as an evolving toolbox open to iteration and further development.

All frameworks and insights, e.g., those described in “Urban Animals”, have the potential to be included and sustained within a Pattern Language for Urban Nature – which needs to have an understanding of the need for cultural change based on biounderstanding at its very core.

An example of a page from “A new pattern language”

Paul Downton

Melbourne

All drawings are by Paul Downton

Lovely, creative entry, Paul! The new Pattern Language book is an exciting project, and I agree that a complimentary “Urban Nature” collection would be very helpful.

Also, I can’t help but think that storytelling approach would be of assistance in the cultural change department. How that fits into the pattern language format, I’m not quite sure yet. Could one re-think the “Discussion” section in this kind of book, so that it follows a narrative, or … specifically adding a “Story” section to each pattern? These are just thoughts. The original book makes great use of visuals and logical reasoning, but doesn’t really ignite the imagination all that much for me.

Why not kick something off together with a few of us here?

Thank you for sharing this easy to follow thinking – it’s beautiful. Biophilic Cities started a pattern library recently but link seems to be broken now. Is that the same outcome you are looking for? https://www.biophiliccities.org/pattern-language-intro

I think having this library would be a useful tool to inspire and share worldwide!

Estoy muy feliz de comprobar que el pensamiento en torno al lenguaje de patrones que inspiro a un pionero en este tipo de enfoque, como Chiristopher Alexander siga vigente a traves de la obra y las reflexiones de nuevos profesionales cientificos y estudiosos de la relacion de las ciudad- naturaleza. En epocas de cambio climatico pandemias y relaciones globales entre culturas diferentes, la necesidad de re encontrar el pensamiento de Alexander se torna evidente.

Hace muchos años en mi epoca de estudiante obtuve una beca para profundizar en la obra de Alexander y su lenguaje de patrones…

Full book is here: http://sustasis.net/APLFGR.pdf

Hi Geoff and Stefan, it’s good to know that you find the article of interest.

Geoff, I’m glad you’re inspired to go further into the fundamentals. It’s a deep dive but worth it.

Stefan, I suspect that we’d agree a lot with each other! And you’re right about the big challenge. If we could only accelerate that co-evolution like we’ve accelerated climate change…

Paul, marvelous to see this application of pattern language to urban nature.

My research is into the emerging ecosystems around urban food and I have long been inspired by Christopher Alexander. You have extended my reading list and inspired me to go further into the fundamentals behind the surface patterns

Nice one Paul! I’ve been thinking and working along some of these lines from a behaviour and system change perspective. In short, I think there is good reason to believe humans can align social, economic and ecological rationalities in relatively stable, long term and placed based settlements and communities. The big challenge now is to somehow accelerate that co-evolution where we can’t afford to wait and hope it will occur on its own, and I completely agree thoughtful urban design can be a big contributor to that.