Even, or perhaps especially, in the midst of a pandemic, the importance of greenspace for human health is becoming more apparent. As we imagine a post-pandemic world, we can learn collectively to reevaluate what matters in our urban centers: diversity, equity, resilience, and of course, a walk in the park.

Emerging dialogue linking biodiversity conservation and public health management is a prime example of such reevaluation. The United Nations’ recent report, “Preventing the Next Pandemic,” offers a valuable argument for the use of ecosystem management as a public health tool. Concurrently, The Nature of Cities site has hosted a global roundtable of urban biodiversity experts assessing the impact of the current public health crisis on urban ecosystems—a resource that has grounded many of the arguments and observations made in this article. As we continue to learn how ecosystem biodiversity and public health influence each other, addressing this interconnectedness in urban areas will be uniquely important—for characterizing the most immediate responses to the pandemic within environments that host a growing majority of the world’s population and some of its most critical biodiversity. The complicated relationship between urban biodiversity and the novel coronavirus offers essential lessons for our post-pandemic cities.

Urban centers and biodiversity must be re-contextualized during our present moment: who uses city spaces? What does use of urban greenspace look like during the pandemic? And how has COVID-19 challenged urban biodiversity management? These questions address the urban ecosystem stakeholders with whom I am most concerned: Homo sapiens, particularly policymakers and urban citizens. Critically digesting their experiences and choices can inform reflections—four are presented here—for equity and resilience in the face of future public health crises. Lessons from the pandemic for research scientists are also incredibly salient, and much has been written about these already. Although an effort has been made to approach this topic from a global perspective, the cities whose stories are examined here are primarily English-speaking for ease of research.

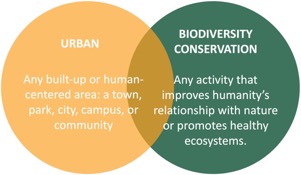

This piece is written to address urban environmental conservation through the lens of a social-ecological system (SES) analysis. An SES is a framework for understanding complex ecosystems in which “multiple sets of actors consume diverse resource units extracted from multiple interacting resource systems in the context of overlapping governance systems.” This definition is challenging to conceptualize and it may help to consider an SES as a unit in which humans interact with natural ecosystems in specific ways informed by institutions. The urban ecosystems with which I am concerned are greenspaces: sites of terrestrial urban vegetation that provide habitats for urban biodiversity, including private yards, public parks, and grassy sidewalks. This definition does not encompass previously developed sites (i.e. brownfields) or bodies of water (i.e. blue space). However, many topics addressed in this article are also applicable to these areas. The living organisms within greenspaces make up the urban biodiversity of the environment (a term that also applies to their structural and functional diversity).

Unpacking Urban Biodiversity and Greenspace Use

Hungry monkeys are roaming the streets of Lopburi, Thailand. The number of Australian backyard bird watchers is soaring. British citizens are using parks more—some littering, others picking it up with greater frequency—than park officials can ever remember.

Around the world, the pandemic has reshaped the relationships between urban dwellers and their natural environments. These relationships are emerging and multidimensional, making them challenging to quantify and assess for significance. Nevertheless, public engagement with nature has long been a cornerstone of conservation and can offer illuminating lessons for biodiversity advocates. Themes of increased and diversified use of urban greenspace have begun to emerge and, importantly, bear implications for public health. However, access to nature is not shared equally by all, necessitating the question:

Who uses city spaces?

In the United States, the early months of the coronavirus pandemic were characterized by narratives of egress from urban centers. Those with the option sometimes left high-risk areas to avoid high levels of viral exposure and to access more affordable living with family and friends; others (those with means) sought safety in rural second homes. But, not all who left urban areas did so willingly—many were evicted.

The ones who remained may not have had much of a choice; either due to lack of economic means or the need to stay near employment sources, particularly for those jobs deemed essential. American cities have witnessed an incredible demand for the services of essential workers. According to the Economic Policy Institute, many of these workers are low-income or people of color, making them highly vulnerable to COVID-19. People without homes have also faced unique challenges; social distancing and quarantining can be especially difficult for those without a safe place to live. Because the pandemic has increased rates of homelessness and evictions worldwide—despite government efforts to make it otherwise—these challenges are increasingly consequential. Those who continue to live and work in American cities in the midst of the pandemic often do so because they lack the means to leave.

In many South and Southeast Asian countries—from India to Myanmar—migration out of cities has occurred with greater magnitude, and in a different fashion: poor, migrant workers have left after their jobs disappeared in cities to head for their rural homes. Around the world, migrant workers who choose to stay at job centers face the prospect of living in packed dormitories, where the virus may easily spread.

The pandemic is shifting the demographics of city users and dwellers worldwide, spurred by urban inequities that are not new but are certainly garnering new attention. Social science scholars often frame these inequities within a question, first proposed by sociologist Henri Lefebvre in 1968: who has the “right to the city?” Our responses help to explain why urban (reverse) migrations are happening and highlight which city amenities need to be made more accessible in an age of sickness, stress, and uncertainty.

For example, patterns of Asian reverse migrations have implied that migrant workers typically work and live in cities temporarily but are not necessarily welcome permanently. In American inner cities (at least in the more affordable ones), vulnerable essential workers may work and live but may have less access to resources, like public parks, that are disproportionately located in wealthier neighborhoods. Likewise, homeless communities have limited rights to greenspace when their desired use—to stay overnight, for instance—does not align with the official intended use of the space. Importantly, many European cities have begun to address homelessness during the pandemic by offering temporary housing in hotels and shelters—a significant first step in synergizing social justice and urban planning.

This is just a small sampling of “rights to the city”-related issues exacerbated by COVID-19. Although a more complete analysis is beyond the scope of this piece, we must address who is living in cities and how they are living there before we can understand how greenspace is used in the age of COVID-19.

What does the use of urban greenspace look like during the pandemic?

Even, or perhaps especially, in the midst of a pandemic, the importance of greenspace for human health is becoming more apparent. Research has long observed the physical and psychological benefits of outdoor access, from improvements in respiratory function and physical fitness to stress reduction. The eminent biologist and conservationist E. O. Wilson was the first to coin the term “biophilia”: humanity’s innate tendency to desire interaction with nature. These benefits for humans provided by the environment are called ecosystem services and are essential to understanding the importance of urban biodiversity.

Advantages for human health become only more poignant as efforts to limit COVID-19 also limit mobility, planning, and social gathering. Resultant stress and reduced exercise opportunities in urban populations have powerfully illuminated the value of greenspace for human health and wellbeing during the pandemic. Worldwide, rural parks and recreation areas have shut down as social distancing mandates continue, and funding and staffing for parks sputter. The result is a perfect storm: suddenly, urban greenspaces have become vital sites for recreation and leisure.

While demand for greenspace has soared globally, accessibility to these spaces has fallen—due in large part to mobility restrictions placed upon urban centers by city officials. In Barcelona, for example, March and April saw the imposition of fines for those caught running and cycling in public areas. France’s lockdown lasted for months, severely limiting access to public space. These observations should not be misconstrued as a call to defy public health measures. Rather, this moment can be harnessed as an opportunity to improve how urban greenspace is used and managed.

Many cities are doing just that. Seattle, Washington has sped up its adoption of new pedestrian-first crosswalks that improve mobility for runners and cyclists. Other urban centers from Mexico City to Berlin are adding bike lanes and considering permanent through-traffic closures on city streets. Experts have already begun to debate whether these changes may be maintained long-term, and what the implications may be for developing greener, more efficient, and less polluted cities.

The pandemic has not only increased urban greenspace use but also diversified it. Outdoor learning modules have been implemented in rural Kashmir to much acclaim. The National COVID-19 Outdoor Learning Initiative in the United States follows in the same vein. Notably, these outdoor education models have had success in European cities— particularly in Germany’s “forest kindergartens”—for decades, where teachers harness the beneficial effects of biophilia in their approach to learning.

Biophilic education has also caught on at home, where children and adults are using citizen science to stay entertained and globally engaged. Urban “bioblitzes”—community events organized to record biodiversity by an interested public have moved to the backyard, where they can continue in a socially-distanced fashion. The online forum iNaturalist is a popular site for the events, which are occurring everywhere from New Hampshire to Kerala. Elsewhere, first-time gardeners are looking to the backyard for sustenance: to reduce their reliance on grocery stores, to develop a new hobby, or even to reduce stress. As the pandemic upends lifestyles and livelihoods, reconnecting with nature offers urbanites a means to adapt.

How has COVID-19 challenged urban biodiversity management?

The pandemic has caused local governments worldwide to go to new—and opposing—extremes when it comes to biodiversity management: some ecosystems are now more highly controlled than ever before, while attention towards others has fallen to the wayside.

Depleted budgets and lost workers have made urban greenspace maintenance an unaffordable or low priority expense for many cities. In Singapore, vegetation has been growing wild and untamed during its “circuit breaker” (lockdown) period, inviting new insects and delighting nature-enthused city residents. Elsewhere, cities under lockdown—notably lacking in traffic and snack-bestowing tourists—have witnessed ever-encroaching wildlife on the lookout for food. Coyotes and foxes in American cities, deer in Nara, Japan, and those pesky Thai monkeys have all forced residents to reassess their relationships with local wildlife.

In some cases, that means striking a balance: Lopburi locals have taken to feeding their monkey visitors, and some residents and business owners argue that humans should be the ones adapting to wildlife, not “the other way around.” Still, urban wildlife experts argue, the return of wildlife is likely to be cut short once cities begin emerging from their lockdowns. Rebounding traffic and reductions in social distancing can deter these curious animal newcomers—for example, some may be disturbed by increasing noise pollution while others who have found new sites for migration and breeding may be interrupted by reemerging humans.

At the other end of the spectrum, the public health crisis has, in some cases, resulted in more highly managed human-wildlife interactions. Local and national officials in China have imposed new regulations upon wildlife markets—largely cited as a possible reservoir of SARS-CoV-2—garnering praise from conservationists and public health authorities. Elsewhere, from Tehran to Tokyo to Venice, city workers are spraying antimicrobials in public areas to stop the spread of the virus, a measure that could have far-reaching implications for ecosystem health.

Some of the negative impacts of returning wildlife in major cities have already begun to draw the attention of city officials. Lopburi has recently begun sterilizing its hungry monkeys to control their rapidly growing numbers and Singapore’s grassy sidewalks have become a point of contention between local nature-lovers and the National Parks Board, which is mandated to maintain roadside greenery. Of particular concern for the Southeast Asian city is a rising incidence of dengue, a disease spread by mosquitoes that use stagnant waters amongst dense vegetation to breed.

Balancing biodiversity conservation, public health, and human livelihoods is no easy task for municipal officials, especially in the midst of a health emergency. Yet, the pandemic has made it abundantly clear that these issues are not independent of one another

Many cities have already proven this point. In Pakistan, the COVID-19 crisis has caused high levels of unemployment in urban areas, spurring the expansion of the country’s 10 Billion Tree Program to make more tree-planting jobs available for those looking for work. Nairobi’s response to COVID-19 has involved expanding city parks for better social distancing and outdoor access, with city officials explicitly approaching public health management as a tool in climate resilience. In Amsterdam, planning for economic recovery post-pandemic has meant the adoption of policies that put human health and conservation first. And, even during its dengue and COVID-19 concerns, Singapore’s National Parks Board has acknowledged locals’ appreciation for more “naturalistic” vegetation and has proposed the expansion of its Nature Ways.

Reflecting on Urban Environmental Management

The following four reflections build upon these stories of COVID-19 experiences, observing ways in which the pandemic can spur us to reimagine urban greenspace and urban areas more broadly. Importantly, responding to the pandemic has occurred across fields of expertise and benefited from collaboration among them. The following insights fall within such distinct fields—social justice, technology, microbiology, and public health—and yet will be most useful if understood by urban residents and researchers alike, regardless of profession. A collective appreciation of the potential to restructure our urban systems with an eye to resilience must begin with an understanding of equity, leading to the first reflection:

Reflection #1: Accessibility is becoming a core value in urban greenspace planning

The pandemic has brought severe cuts to city budgets worldwide as unemployment rates jump and city revenue falls in the face of soaring public health expenditures. When push comes to financial shove, city park budgets are often the first to fall. Deciding which greenspaces remain open or maintained can be a highly political act as access is not equally distributed across the socioeconomic regions of most cities.

“Right to the city” literature can be a valuable framework for defining best practices as cities manage budget cuts in order to establish greater inclusivity in nature post-pandemic. Especially in light of the many beneficial ecosystem services that greenspaces may offer for public health, it is important to recognize that marginalized groups have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. That is, the people who have suffered the most from the pandemic are often also those with the most limited access to greenspace and ecosystem services. Therefore, recovery efforts must seek to redress these inequalities.

Collaboration between the spheres of urban planning, parks management, and public health will be key to addressing these inequities and powerful conversations among stakeholders have already begun to gather momentum. For example, integrating social justice principles within spheres of architecture and urban design is helping to re-conceptualize the functionality of citiesconcerning city user demographics. Simultaneous efforts to engage underrepresented groups—students of color, for instance—in urban ecosystem management are paving the way for more equitable greenspace use.

Reflection #2: Technology can be adapted as a resource for conservation

In response to the pandemic, cities, educators, and families have applied technology in creative ways to strengthen biodiversity engagement and management. Citizen science ventures accessed via smartphone have opened doors for communities to learn more about their local ecosystems and contribute to biodiversity conservation in the process. In an effort to support social distancing, parks departments had developed online mapping tools to inform greenspace users of activity and crowd levels by area.

Emerging technologies have also been co-opted to monitor and manage public health. Nairobi’s new air-quality sensors will provide valuable data about air pollution, a boon not only for managing environmental risks associated with COVID-19 but also for tracking ecosystem health. New York City’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority has opted not to use antimicrobial chemicals in some of its efforts to sanitize subways and buses, choosing UV light-emitting robots instead. Robots have also been employed in Singapore, where they’re programmed to roam public parks and encourage social distancing.

Whether or not these technologies are explicitly intended to target the environment, many of them have the potential to link communities more strongly with nature and to aid in more efficient and less damaging ecosystem management. Yet, as the pandemic challenges cities to become “smarter” and “greener”, it will be more important than ever to remain mindful of Reflection #1 (accessibility) and to implement technology in ways that are equitable and globally productive. Asking where and how technology will be use—and inevitably, who will use it—can serve these goals.

Reflection #3: Broadening perceptions of ecosystem services to include the microbial world can benefit public health

In recent decades, the emerging fields of microbial and disease ecology have shown us that greenspaces have the potential to affect human health in ways beyond traditional understandings of ecosystem services. That is, our appreciation of nature as a source of clean air and clean water and a site for physical exercise and mental rejuvenation is expanding to include ecosystem services that act at the microscopic level. Microbial ecosystems (i.e. “microbiomes”) have become more common in public vernacular; with respect to the human microbiome, for example, the benefits and detriments of probiotics and antibiotics are becoming well-known by the general public.

Growing widespread awareness of the human microbiome is an exciting first step in microbiology-based public health education. Yet, portraying the human microbiome as an independent entity limits the effectiveness of these efforts: challenging and broadening our understanding of the human microbiome to better address the greater microbial ecosystem should be a central aim of future microbial ecology research. Researchers, for example, have recently proposed re-imagining humans as “holobionts:” living, breathing microbial ecosystems whose members interact with other microorganisms in the greater environment.

This concept is especially useful for municipal public health dialogue, as it helps to inform how we frame urban ecosystem services. For example, reduced microbial biodiversity in the so-called “urban microbiome” has been documented and may have broad effects on human health. The hygiene hypothesis is a classic explanation of this proposed phenomenon, predicting challenges to immune system development in more developed, sterile environments. Recently, links between human health and human and ecosystem microbiota have been expanded to encompass even more disease outcomes, from the transmission of diseases to humans from other animal species (zoonoses) to the development of multiple sclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease.

The COVID-19 crisis offers a unique opportunity to contribute to this growing body of evidence. Of particular significance are emerging studies that propose limited coronavirus transmission in outdoor settings and possible links between asymptomatic infections and previous exposure to other coronaviruses. As the pandemic modifies human-environment interactions across ecosystems—whether through the wide-spread spraying of antimicrobials or the growing presence of urban wildlife in many cities—it will be exciting to uncover how urban microbiomes have also changed.

Applying microbial ecology to urban planning and ecosystem management is a second avenue along which we can refine our perception of the urban microbiome. Increasingly, the confluence of public health, urban planning, and microbiology is trending towards a narrative of rewilding: re-introducing biodiversity at a macroscopic level to stabilize and diversify the urban microbiome, and thus improving public health and ecosystem health outcomes. This model of ecosystem reorganization is intended to make the urban social-ecological system self-sustaining, with minimal demand for ongoing management. The Healthy Urban Microbiome Initiative and Microbiome-Inspired Green Infrastructure have emerged to extend these efforts into spheres of public education and urban management.

Reflection #4: Recognizing synergies between public health, urban planning, and greenspace use will be the key to preventing future pandemics

The reflections above have implications for targeting environmental management in distinct and yet highly connected ways. For example, greenspace accessibility, technology, and public health methodologies may all affect ecosystem health and biodiversity. In turn, natural actors may influence various social components of a given social-ecological system. Antimicrobial resistance, for instance, is a result of a social practice—the growing use of antibiotics in medical and agricultural industries—that had an environmental consequence— the increasing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant “superbugs.” What emerges is a highly interconnected social-ecological system from which indirect and unintended consequences can arise. No species—human or otherwise—or habitat type—urban or otherwise—can be independent of this system.

This social-ecological system concept has been applied in public health policy with increasing frequency, perhaps most notably within the World Health Organization’s One Health model, an approach to public health policy that uses expertise from many sectors of ecosystem management, such as food safety and animal health, in its responses to disease. Addressing the COVID-19 crisis has demanded collaboration across these spheres of management and experts identify One Health as a keystone feature in planning to prevent future pandemics.

Benefits of the One Health approach are not necessarily one-sided; what is good for humans can be good for ecosystems, too. Ecosystem management is an essential cornerstone of conservation and active public participation in greenspace management has been shown to strengthen biodiversity.

Actions informed by synergies between human and ecosystem health are already being undertaken—many of which have been mentioned here. Furthering this work in urban ecosystems, in particular, will be an important next step, and will benefit from approaches that also adapt expertise in urban planning, education, and social justice. Notably, cities’ best practices for responding to COVID-19 include changes to waste management systems, food systems, and ways of addressing housing and poverty—aspects of urban ecosystems that are also highly significant for this article but beyond its scope. Many of these municipal responses utilize principles of a One Health approach, although none address the model in its entirety—likely because the model was largely crafted for public health management at the national level and operates through national bureaus and agencies. Developing One Health schema for use at the local level is a promising strategy for grassroots global health efforts, especially as discussions concerning potential future pandemics proliferate.

What the COVID-19 pandemic has made most clear is that we live in a globalized world—our social-ecological systems are highly connected and highly complex. Of equal complexity are humanity’s responses to this crisis; they have yielded mixed results but are not without innovation and compassion. The stories of loss and change-making told within this article reflect all of these themes but are less universal truths than context-specific examples of urban management in the pandemic age. That is, there is no “right way” for all cities to overcome COVID-19. Rather than provide a list of best practices for current public health and urban environmental management (which would inevitably be lacking), this article acts as a conversation starter for a diverse and multidisciplinary dialogue. As we begin to imagine a post-pandemic world, we can learn collectively to reevaluate what matters in our urban centers: diversity, equity, resilience, and of course, a walk in the park.

Kaja Aagaard, with Mika Mei Jia Tan and Jennifer Rae Pierce

Middlebury, Los Baños, Vancouver

about the writer

Mika Mei Jia Tan

By night, Mika Mei Jia Tan leads the Urban Biodiversity Hub’s Steering Committee. In the day, she is Coordinator of the ASEAN Youth Biodiversity Programme at the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Biodiversity Centre. An interdisciplinary thinker, she holds a B.A. in Environmental Studies (Conservation Biology) from Middlebury College, USA.

about the writer

Jennifer Rae Pierce

Jennifer Rae Pierce heads the Urban Biodiversity Hub’s Partnerships and Engagement team and is a steering committee member. She is a political ecologist and urban biodiversity planner. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver on the topic of engagement in urban biodiversity planning.

Leave a Reply