But the challenges on progressing from ideas and designs to realizing and implementing nature-based solutions in cities remain: departmental divides and silos, “projectification” of the work, prioritization of opportunity-driven projects instead of strategic long-term investments in nature, and sustainability in the city are just a few; all well-known and recognized by the cities. Researchers have spent significant time documenting and systematizing these challenges, showing how they block progress and planning innovations in cities. Restating the obvious and the well-known will not help cities move forward nor discover ways to navigate and to progress the practice and co-produced knowledge on nature-based solutions.

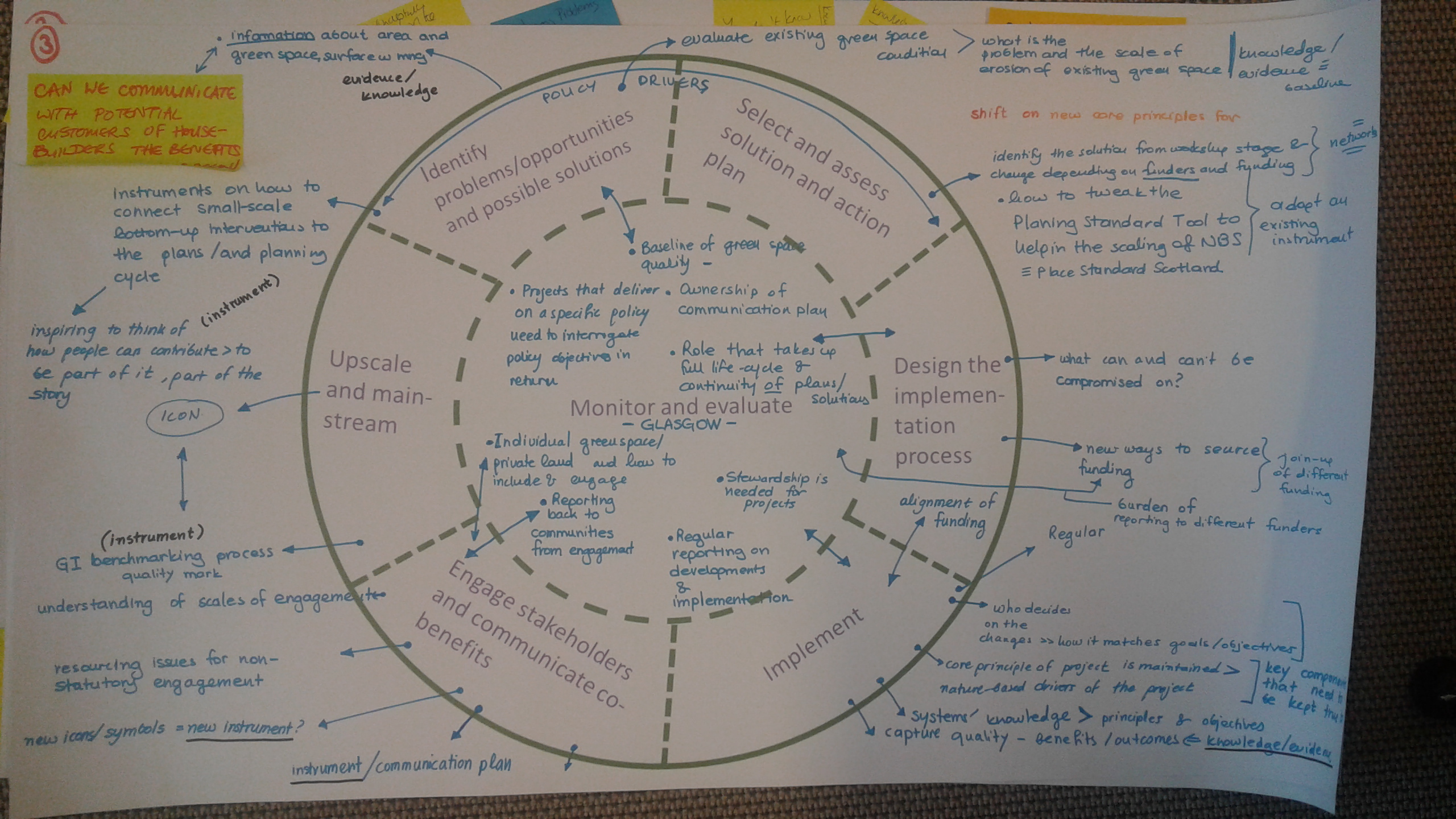

In an attempt to shift the focus to “what we need to bring nature to the city”, we worked collaboratively and co-creatively with three leading cities in Europe that have in their strategic envelope to implement large-scale nature-based solutions:

- Glasgow, in Scotland with the transformative plan to turn all open spaces into multifunctional spaces with nature-based solutions (Link: https://www.glasgow.gov.uk/openspacestrategy).

- Poznań, in Poland, with the systemic plan for complementing the green wedge and ring system with small-scale nature-based solutions that connects existing green spaces with kindergartens yards that are transformed into nature-based playgrounds; (Link: https://connectingnature.eu/city-pozna%C5%84-social-gardens-exemplar).

- Genk, in Belgium, with the resilient plan to create a large-scale linear park – the Stiemer Valley Nature-based Solution Exemplar – as a corridor of connections (connecting people with nature, people with people, and entrepreneurs with nature) and a flood protection zone of the city (Link: https://www.genk.be/stiemervallei).

All these cities identified how new approaches and new frameworks are needed for shifting the focus and dialogue from what ‘blocks us’ to what we need in place to move forward with nature-based solutions. As a proposal, we crafted a conceptual framework on three policy needs as “interrelated processes and conditions” for successful implementation of nature-based solutions in cities: knowledge, skills, and partnerships. To put simply: Poznan for urban planners and urban strategists to bring solutions from the area of a “concept” to the city life, they need a mix of knowledge about the “what”, “where”, “how” and “for whom”, skillful collaborators and colleagues to go through the process of planning and implementation, and to work collaboratively, as cities and their solutions are partnership projects.

First, identifying knowledge needs is a core step to bridge practitioners’ knowledge to new technical and scientific knowledge for designing, selecting, managing, and implementing nature-based solutions. As knowledge is ever-evolving and, at times, co-produced in response to socially complex problems, cities need to be able to identify what type and in which form knowledge is required for implementing nature-based solutions.

All cities noted that a systems’ thinking is essential for guiding the selection and to be part of the design of nature-based solutions. Why is that so? Systems thinking allows them to recognize and find ways to bridge the multiple bit of knowledge, ideas, and expertise needed for designing and selecting nature-based solutions.

Another cross-cutting identifiable knowledge need is about methods and approaches to enable evaluation and monitoring of how nature-based solutions perform on the ground in addressing diverse urban challenges as well as how to capture policy and social learnings of living in cities with nature.

Next to these, the cities require new thinking alongside new business model knowledge on turning critical infrastructure such as nature-based solutions into business opportunities and enabling platforms for green jobs and investments. This will allow cities to see the short and long-term benefits of such investments, especially in contrast to conventional grey solutions.

Second, nature-based solutions are designed, managed, implemented, and monitored by people in the cities. The city officials, including planners, strategy developers, engineers, ecologists, landscape architects, and asset managers have different skillsets and capabilities and, often, it is those new skills that require investment, patience, and capacity building to allow them to combine current and new skills into bringing nature-based solutions to the city life.

All cities noted the importance of communication skills, pointing to how important it is to have, not only a common narrative, but also the ability to communicate what makes a nature-based solution and what the multiple benefits of this solution are across different departments of the city administration as well as to different communities of interest. However, communication skills need to build the diplomacy, advocacy, and translation of knowledge (from technical to planning and community-related) skills of urban planners throughout the different planning phases.

Third, nature-based solutions as sustainability solutions require multiple actors so that they are co-designed and need to be considered as well as foreseen impacts. As urban solutions, nature-based solutions need the support and the integration in the urban fabric to be able to be operational and effective, and that requires the collaboration of multiple actors.

All cities noted how important it is to build partnerships for knowledge/expertise as well as for support across different departments of the city, including political support for nature-based solutions. Cities noted the importance of social support and social capital through partnerships with communities and civil society as well as the political capital and support required to enforce and sustain nature-based supportive policies and projects.

Looking at the identified needs of cities to bring nature to urban life, there are three key lessons we want to bring to other cities as well:

First, investigate and examine what knowledge needs to have rather than identifying what is lacking or missing. A change of perspective to “what it is needed to know” will help not only tapping into knowledge from recent research, finding collaborators that have the needed knowledge resources but also require targeted and tailored capacity-building programs to meet identified knowledge needs. Related to this, it is important to keep in mind that knowledge needs may include technical, financial, organizational as well as procedural (process-related) needs for nature-based solutions and can be addressed in various ways.

Second, approach nature-based solutions as solutions that not only require but also can enable social and policy learning. For cities, it is important to allow or create spaces for learning (for example with reflexive monitoring) for, with, and about nature-based solutions. These learning spaces can take different forms from rethinking city festivals, to co-production processes, to real-life laboratories or urban living labs, to museums and parks utilized as learning and engagement spaces.

Third, think and seek for enabling innovations throughout the process of designing, co-producing, delivering, implementing, and co-managing nature-based solutions in cities. That means not only bringing different innovations and innovators together along the way but also gather evidence (through monitoring and systematic evaluation) of which innovations are effective and transformative in the quest of bringing nature-based solutions to urban reality[1].

Niki Frantzeskaki, Paula Vandergert, Stuart Connop, Karlijn Schipper, Iwona Zwierzchowska, Marcus Collier, Marleen Lodder

Melbourne, London, London, Rotterdam, Poznań, Dublin, Rotterdam

Read more about this research:

Frantzeskaki, N., Vandergert, P., Connop, S., Schipper, K., Zwierzchowska, I., Collier, M., and Lodder, M., (2020), Examining the policy needs for implementing nature-based solutions: Findings for city-wide transdisciplinary experiences in Glasgow, Genk and Poznan, Land Use Policy , 96, 104688, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104688

Dumitru, A., Frantzeskaki, N., Collier, M., (2020), Identifying principles for the design of robust impact evaluation frameworks for nature-based solutions in cities, Environmental Science and Policy, 111, 107-116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.05.024

Frantzeskaki, N., McPhearson, T., Collier, M., Kendal, D., Bulkeley, H., Dumitru, A., Walsh, C., Noble, K., van Wyk, E., Pinter, L., Ordonez, C., Oke, C., Elmqvist, T., (2019), Nature-based solutions for urban climate change adaptation: linking the science, policy and practice communities for evidence based decision-making, Bioscience, 69, 455-566, doi:10.1093/biosci/biz042

Links of related material for practitioners and city makers (free and open access):

On impact assessment for nature-based solutions

On reflexive monitoring of planning process for nature-based solutions

On various forms of innovations related to nature-based solutions

[1] In the Connecting Nature project, we co-produced a framework that encompasses all the different innovations in one iterative process. The framework is a process tool to help cities and other organizations navigate the path towards the large-scale implementation of nature-based solutions. For more information see: https://connectingnature.eu/innovations/connecting-nature-framework

About the Writer:

Paula Vandergert

Dr Paula Vandergert is a Senior Research Fellow in the Sustainability Research Institute, University of East London. She works with local authorities, strategic development organisations and local community groups on adaptive governance methods for sustainable and resilient communities and places.

About the Writer:

Stuart Connop

Dr Stuart Connop is an Associate Professor at the University of East London's Sustainability Research Institute specialising in biomimicry/ecomimicry in urban green infrastructure design.

About the Writer:

Karlijn Schipper

Karlijn Schipper works as an action researcher and advisor for the Dutch Research Institute of Transitions (DRIFT). Her topics of interest include urban inclusive change, just transitions and reflexive monitoring.

About the Writer:

Iwona Zwierzchowska

Iwona Zwierzchowska is an assistant professor at the Department of Integrated Geography at the Faculty of Human Geography and Planning at the University of Adam Mickiewicz in Poznań. Her research interest focus on urban ecosystems and human-nature interactions in an urban context.

About the Writer:

Marcus Collier

Marcus is a sustainability scientist and his research covers a wide range of human-environment interconnectivity, environmental risk and resilience, transdisciplinary methodologies and novel ecosystems.

About the Writer:

Lodder Marleen

Marleen Lodder graduated MSc Architectural Engineering at Eindhoven University of Technology with honours in 2010 and worked as a Ph.D. candidate (October 2011-2015) at DRIFT, Erasmus University. Her research focuses on how urban area development in the Netherlands can become beneficial, by generating economic, ecologic, and social cultural values.

About the Writer:

Niki Frantzeskaki

Niki Frantzeskaki is a Chair Professor in Regional and Metropolitan Governance and Planning at Utrecht University the Netherlands. Her research is centered on the planning and governance of urban nature, urban biodiversity and climate adaptation in cities, focusing on novel approaches such as experimentation, co-creation and collaborative governance.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation