Putting nature at the heart of recovery thinking is an argument we read and hear since the beginning of the COVID19 pandemic. Will we act on this argument? If not, it is just a new greenwash.

But, casting a closer eye, the positive image gets blurred: are these greenwashing measures or radically transformative measures for a green recovery? Are the bike lanes and cycling infrastructure a “band aid” approach to the deeply rooted perception and value that automobility is the dominant mode of transport? Or are bike lanes the tactical urbanism experiment that will inform and quickly connect to an integrated low-carbon mobility plan to inform investment and divestment simultaneously? Are there plans for improving quality and accessibility of urban parks across the city and especially in economically vulnerable areas? Or are lush parks in areas or locations with investment potential in cities planned and funnel investments instrumentalising the crisis to move forward at the expense of areas that need green space improvements more?

With these questions in mind, we need to both wait for the post-pandemic recovery plans to unfold before we critically examine and assess them (preferably om relation to the Sustainable Development Goals) and at the same time, seize the opportunity for a science-based and science-driven advocacy narrative towards more radical, transformative actions to progress our cities and urban living towards sustainability, resilience, and liveability. Such discussions happen now across the globe also as part of UN’s declaring this decade as the UN decade for Ecosystem Restoration (#GenerationRestoration) as a global aspiration for restoring our nature at all scales and geographies.

Earlier this month, I had the opportunity to participate in a panel of the European Union’s Green Week 2021 on this exact topic question: What transformations we need for a green recovery of our cities post pandemic? Based on recent research and long-standing research findings, I presented three interlinked proposals of transformative actions to build resilience with a focus on gearing up a green post-pandemic recovery. This essay is to share my insights and hopefully, ignite a discussion on the post-pandemic recovery we want to see in our cities and by our cities.

City leadership needs to be strengthened

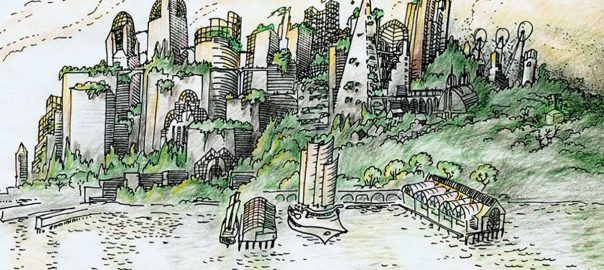

First, cities—meaning local governments—need to continue charting the way in building resilience through city leadership regionally and globally. What we have evinced the past two decades with cities being on the forefront of innovating and experimenting with new policy arrangements, bold and iconic greening and renaturing projects need to be further strengthened and mainstreamed. The city as a governance level but also as a habitat unit is the scale in which coupled climate and biodiversity solutions can emerge and be strengthened. In our recent research (Oke et al 2021), we believe that cities can play a major role in dealing with biodiversity crisis especially through reconnecting people with nature through engaging with citizen science, empowering Indigenous communities and appreciating their knowledge. City leadership should be the foundation for a post-pandemic recovery for building resilience through innovation, solution finding and place-based interventions that strengthen communities and their connections to nature. City leadership needs to be strengthened because cities are nature’s habitats as well. In a post-pandemic recovery plan, state and federal governments need to devolve power in terms of authority to legislate, propose environmental plans and biodiversity action plans to cities. Empowering and capacitating local governments can be a driving force for a combined climate and biodiversity recovery that does not get blocked nor stalled by complex and entrenched bipartisanship politics that often are not about long-term sustainability and resilience.

Adopt a system’s perspective as a way-finder

Second, recovery measures should not be ad-hoc and opportunistic but rather guided through a system’s thinking perspective. Cities as mosaics of infrastructures and people’s routines, uses, and meanings need to be understood and planned through a system’s approach. This means understanding how infrastructures and the social environment interconnect and co-evolve, how the feedback loops of complex change processes can provide insights on interventions with amplification effects (Frantzeskaki et al 2021). Think on how changes in neighbourhood streets or parking lots in terms of landscape, use and functionality can trigger changes in micro-environmental conditions if they are unsealed and how such changes can be catalysts for more civic engagement and attachment to place if these spaces are re-appreciated and appropriated as an urban common.

What urban planners and urban strategists can do by adopting a system’s thinking for formulating the recovery plans is to put people at the centre of system’s thinking and adopt this approach not only as a diagnostic but also as a way finder for more transformative solutions for urban resilience. Putting people at the centre of system’s thinking means that we unpack and understand how citizen’s behavior responses, practices form institutions that strengthen or weaken feedback loops and how these responses and practices can swift towards new system configurations. Think, for example, of shifting to household recycling and recovery of resources instead of ‘all-in-one’ waste disposal practices and how this can support more circular city models, and sharing economy district approaches. Instead of investing in large waste infrastructure first, circular economy investments need to come hand in hand with understanding human practice and behavior and how it can trigger and be triggered through new urban design, household level technologies and even economic or “award-type” incentives.

Green recovery and low-carbon urban transitions to be mutually reinforcing agendas

Recovery plans and agendas have to avoid reinforcing unsustainable ways of living and chart new ways of organising, living, relating and thinking. We have a unique chance to reimagine our cities and urban lives being sustainable and resilience at present: here and now. A way forward is to see the green recovery plans reinforcing and creating synergies with low-carbon transitions. In many cities this is already happening, but more strategic plans need to be put afoot. Investing in infrastructure modifications to make neighbourhoods walkable for all can also have health benefits for citizens (e.g., dealing with obesity and overweight related issues) (Hadgraft et al 2021). And in the quest to make cities resilient one neighbourhood at a time, urban planners need to keep in mind that not all greening and greenness matters the same when it comes to health impacts and wellbeing: urban parks and larger green spaces when accessible and in proximity are not only appreciated and connect people to nature but also lower cardiometabolic risk of urban citizens (Hadgraft et al 2021). By making urban neighbourhoods walkable and green, we can chart an urban pathway of low-carbon and healthy resilient living.

Relatedly, putting nature at the heart of recovery thinking is an argument we read and hear since the beginning of the COVID19 pandemic. There is longstanding evidence that nature-based solutions as the umbrella of green and blue infrastructure measures, sustainable urban water drainage systems, ecosystem-based adaptation measures, and more have the potential to deal with climate change, be climate adaptation solutions while addressing socio-economic challenges simultaneously (European Commission, 2021; Frantzeskaki et al 2019). This again points to recovery agendas that include regenerating urban infrastructures in cities and transforming places through greening into urban green commons. As transdisciplinary and transformation-oriented scientists we need to be critical and instrumental in this recovery agendas: being critical and investigative that this unique opportunity for a green leapfrogging does not turn into an exploitative greenwashing opportunity at the expense of both biodiversity and people living in cities. It needs to be seized as a way forward and above the non-sense measures or touching-the-surface of the problem political masking or maneuvering and enforce radical and transformative agendas for people and the planet. And as this may reads as a manifesto, it is merely what many researchers and a hundreds of hours of documentaries on the state of the planet, the urgency to deal with climate change have been pointing at, and the pandemic has brought us with an unmet opportunity or a policy window to accelerate the action advocated and supported at large.

However, this needs to be done in an inclusive way, considering multiple actors, knowledges, as well as a system’s thinking for design, management and maintenance (Frantzeskaki et al 2020). In view of this, we need to consider that a green recovery of our cities is a multi-actor project. Collaboration is catalytic for co-design and co-create nature-based solutions with social innovators and citizens including Indigenous communities and not-easy-to-reach groups to make recovery just, equitable, and inclusive.

Niki Frantzeskaki

Melbourne

References

Elmqvist, T., Andersson, E., Frantzeskaki, N., McPhearson, T., Folke, C., Olsson, P., Gaffney, O., and Takeuchi, K., (2019), Sustainability, resilience and transformation in the urban century, Nature Sustainability, 2, 267–273 — https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-019-0250-1, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0250-1

Frantzeskaki, N., McPhearson, T., Collier, M., Kendal, D., Bulkeley, H., Dumitru, A., Walsh, C., Noble, K., van Wyk, E., Pinter, L., Ordonez, C., Oke, C., Elmqvist, T., (2019), Nature-based solutions for urban climate change adaptation: linking the science, policy and practice communities for evidence-based decision-making, Bioscience, 69, 455-566, doi:10.1093/biosci/biz042

Frantzeskaki, N., Vandergert, P., Connop, S., Schipper, K., Zwierzchowska, I., Collier, M., and Lodder, M., (2020), Examining the policy needs for implementing nature-based solutions: Findings for city-wide transdisciplinary experiences in Glasgow, Genk and Poznan, Land Use Policy , 96, 104688, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104688

Frantzeskaki, N., McPhearson, T., and Kabisch, N., (2021), Urban Sustainability Science: prospects for innovations through a system’s perspective, relational and transformations’ approaches, AMBIO, 1-9, doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01521-1

Hadgraft, N., Chandrabose, M., Bok, B., Owen, N., Woodcock, I., Newton, P., Frantzeskaki, N., and Sugiyama, T., (2021), Low-carbon built environments and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review of Australian studies, Cities & Health, DOI: 10.1080/23748834.2021.1903787

Oke, C., Bekessy, S., Frantzeskaki, N., Bush, J., Harrison, L., Grenfell, M., Hartigan, M., Gawler, S., Callow, D., Elmqvist, T., Garrard, G., Fitzsimons, J., Cotter, B., (2021), Cities should respond to the extinction crisis, Urban Sustainability 1, 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-020-00010-w

Leave a Reply