The River Avon

Most visitors to the city of Bath in the West of England come to enjoy its grandiose Georgian crescents, terraces, and squares, and Roman-built baths, which have been beautifully crafted from the locally mined honey-colored oölitic limestone. Indeed, the city’s magnificent architecture and Roman remains have been recognized by UNESCO, which has designated the city a World Heritage Site. While I also marvel at the beauty of these historic human-made structures, what draws me back to the city where I lived and worked for many years is its natural history, and in particular, the wildlife of the River Avon on which the city was founded.

The River Avon meanders its way for 83 miles from its source on the south-eastern slopes of the Cotswold Hills, through the cities of Bath and Bristol, to its confluence with the Severn Estuary at the port of Avonmouth. As there are eight “River Avons” in Britain, to distinguish our one from the others it is sometimes referred to as the Bristol Avon. The frequent occurrence of the name Avon derives from its ancient Celtic meaning — river — and hence the words River Avon means “River River”!

The Fall and Rise of British Rivers

The Bath section of the River Avon and countless other urban rivers in the UK were, over many years, ecologically degraded and transformed by human activity and resource exploitation, including urban development, water abstraction, pollution, disturbance, and catchment hardening. London’s Natural History Museum, for example, declared in 1957 that the River Thames was “biologically dead”, with news reports at the time also describing the river as a vast, foul-smelling drain with virtually no oxygen.

However, over the last 30 years or so the water quality of urban rivers throughout Britain has, in general, improved appreciably due to deindustrialization, stronger environmental regulations, and improved wastewater treatment (Vaughan & Ormerod, 2012). The River Avon is no exception and is now a much-improved fishery, including healthy populations of Bream, Chub, Roach, Carp, Pike, Barbel, Perch, Tench, Trout, and Dace (Keynsham Angling Association, 2021). With the return of their prey Otters have also recolonized the Avon, including along the Bath and Bristol sections of the river. The Bath stretch of the river is also an important corridor for rare commuting/foraging Greater and Lesser Horseshoe Bats that roost in caves and abandoned mines in surrounding hills, while riverine insect life includes flamboyant mayflies and Banded Demoiselle damselflies. Finally, an impressive assemblage of bird species can be encountered along the city’s river corridor, which is the focus of this article.

The Biophilic Benefits of Birds and COVID-19 Lockdowns

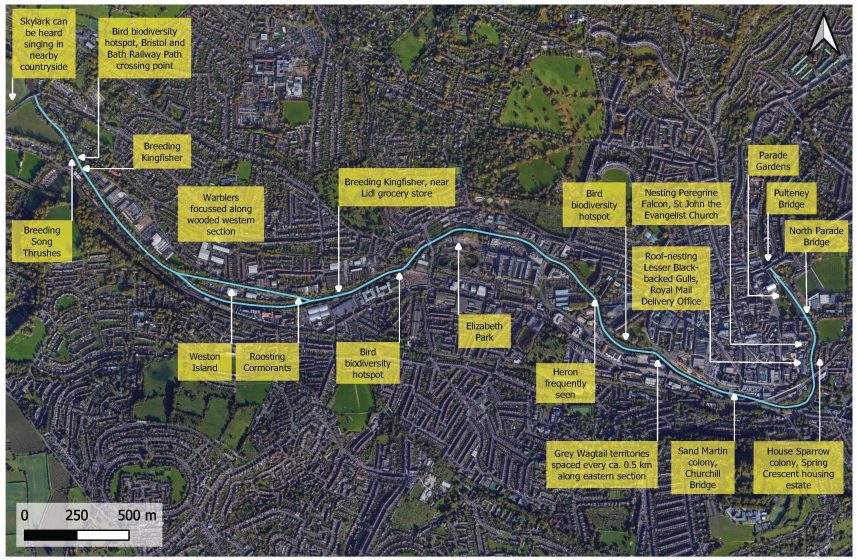

The local council, Bath and North East Somerset, is seeking to enhance biodiversity and recreational access along the city’s riverwalk, known as the Bath River Line (BRL). To help establish a baseline for future monitoring of the BRL, we were asked by the council to carry out a breeding bird survey throughout spring 2021, concentrating on the 5.2 km section that extends from the center to the city’s western limits. Birds are considered a good indicator of environmental change because they are highly mobile and typically occupy high trophic levels in food webs, and thus they are very sensitive to changes in invertebrate populations, and vegetation cover and composition (Suri et al., 2017).

Surveying breeding birds gives me more pleasure than any other ecological survey. The wide diversity of bird species and their behaviors, including the variety of songs, provides a rewarding multisensory experience. I also derive much satisfaction from singling out individual species from the cacophony of the dawn chorus, plotting individual territories, and identifying relationships between the distribution of species and habitat type. Birds also capture the wider public’s imagination more than most other fauna, which in part relates to their variety but also because so many species can be readily observed and enjoyed. Moreover, presence of various scarce and charismatic species along urban rivers raises the public’s perception of these rivers as ecologically healthy and functional systems, inspiring interest in their protection and ongoing restoration.

Because of the COVID-19 lockdowns and associated reduction in noise pollution, multiple media stories have also described how many people have become increasingly aware of their natural surroundings, and particularly of birdsong and the psychologically healing (biophilic) effect that nature’s soundscape can have. This is not simply an intuitive understanding; scientific evidence is also revealing a positive relationship between birdsong and mental wellbeing (Bakolis et al., 2018; Harkness, 2019; Lovatt, 2021). In telling the story of BRL’s birdlife I hope to also encourage even greater interest in birdlife that might help in these difficult times deliver an enhanced dose of “Vitamin N” or “Nature’s Fix”, to borrow the biophilic terminology of Richard Louv (2017) and Florence Williams (2017) respectively.

Auto-rewilding and Adaptations to Climate Change

Analysis of BRL’s breeding bird assemblage can also tell us much about how certain species are, without direct human intervention or ongoing management, adapting in surprising ways to the new, varied, and fluctuating conditions of “novel”intensively human-modified environments, as well as to climate change.

Without the former process, which is sometimes referred to as “auto-rewilding”, much of our urban realm would be devoid of nature and the biophilic benefits described (Tsing, 2019; Clancy & Ward, 2020). Moreover, recognizing how different birds and other species respond to the challenges of the urban realm is fundamental if we are to support auto-rewilding processes through management interventions seeking additional opportunities for wildlife to flourish.

Breeding Bird Numbers

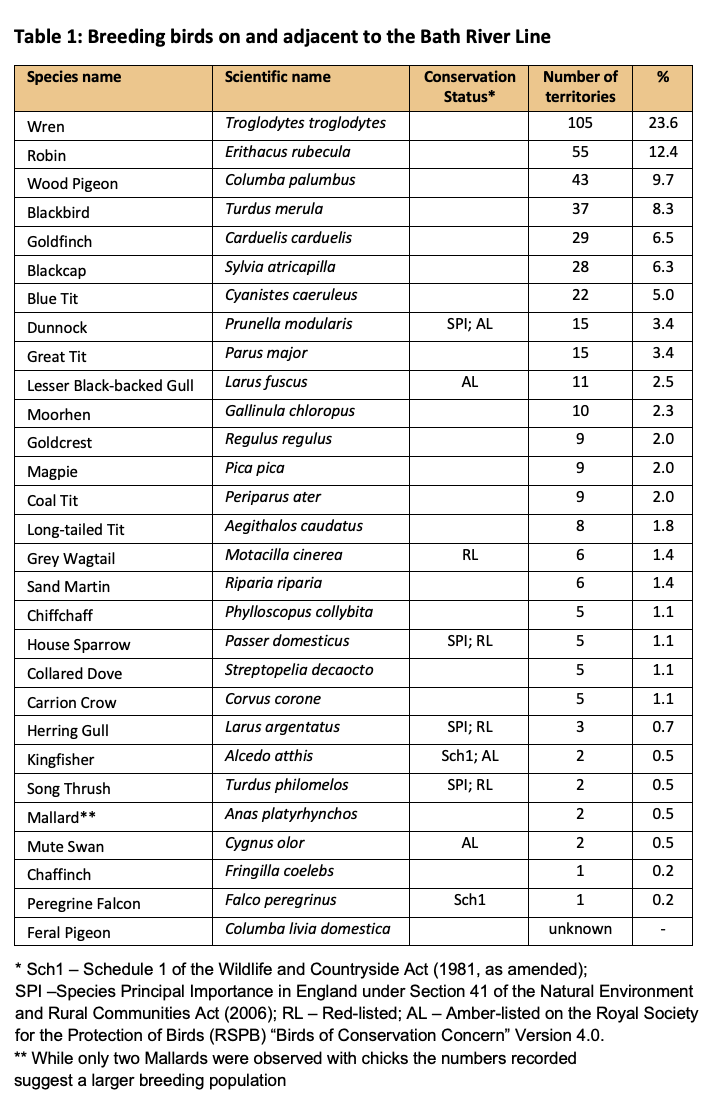

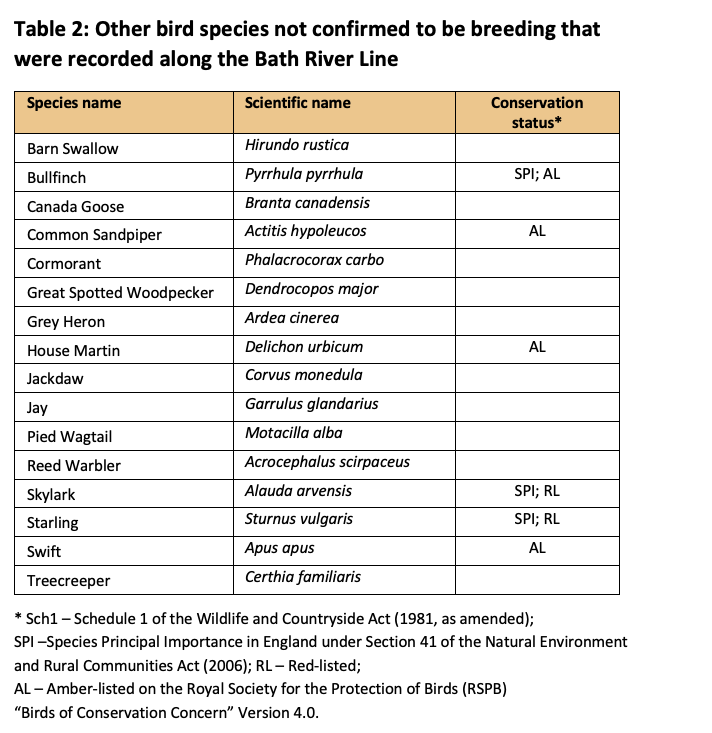

Over five survey visits, I recorded forty-four bird species along the BRL corridor including within adjoining parks. Of these 28 were probably breeding, occupying at least 450 territories (see Tables 1 and 2). The breeding birds that I recorded that are protected and/or of conservation concern included: Peregrine Falcon (Schedule 1), Kingfisher (Schedule 1 & Amber listed), Song Thrush, House Sparrow, Herring Gull, Grey Wagtail (all four are Red listed), Dunnock, Lesser Black-backed Gull, and Mute Swan (all three are Amber listed). Schedule 1 listed species are legally protected in the UK under the Wildlife and Countryside Act. Red list species are considered by leading wildlife bodies in the UK to be of the highest conservation priority, whereas Amber is the next most critical group. Figure 1 shows key geographical reference points referred to in the article, as well as the survey’s avian “highlights”.

Eastern Section of the BRL

The Usual Suspects

My visits to the BRL commence in the city center at one of Bath’s pre-eminent architectural attractions, Pulteney Bridge. Completed in 1774 the bridge is one of only four bridges in the world to include shops across its full span on both sides. Taking the spiral stone staircase, I descend from the bridge to the riverside and immediately hear the song of a Blackbird despite the omnipresent roar of city-center traffic and cascading water from the nearby weir. This prolific singer with its marvelously diverse repertoire is often perched on top of the bridge or the lead-covered dome of the adjoining Victoria Art Gallery. Blackbirds and some other species have been found to sing at a higher pitch (frequency) in urban environments compared with their rural compatriots, a behavioral trait that might in part be an attempt to escape the lower noise frequencies (particularly from vehicles) of the urban environment (Ripmeester et al., 2010).

After walking only a short distance, I am opposite Parade Gardens, considered an exemplar Victorian public garden including a bandstand and floral bedding displays. From these gardens as well as riverside trees, I start to hear the songs of Wren and Robin, the two most abundant breeding species along BRL. Their contrasting songs are the dominant constituents of “nature’s soundtrack” along the length of the river walk, as they are in numerous other habitats across the UK. Although diminutive in stature, the Wren compensates with its remarkably powerful and rapid song, which can be heard on average every 50 m along the BRL. Complementing their explosive series of trills, the Wren is also made conspicuous by its low, fizzing, almost insect-like flights, and its incessant bobbing when perched. Conversely, the song of the Robin is a mellow and sweet (if a little wistful) warble, and the bird generally gives the appearance of being less hurried in its movements. The year-round almost unceasing song of the Robin combined with its tameness ensures that this popular bird, recently voted the UK‘s most loved bird in a national pole, can be easily spotted. Along with the Blackbird, Robins typically introduce the dawn chorus across much of the UK and can even be heard singing throughout the night, behavior thought to be stimulated by street and other artificial lighting that is deceiving them into thinking there is no end to daylight.

My rising spirit is elevated another notch from hearing the cheerful jingling calls of Goldfinches, as parties of these sociable birds flit through the riverside canopy. With their clown-like bright red faces and gold wing patches, they certainly bring a splash of color to any walk. This colorful finch has flourished in the “new wild” of the urban realm, a trend potentially linked to the copious supply of bird food available in British gardens, although warmer winters linked to climate change might also be playing a part (Plummer et al., 2019). Amazingly, at least half of British homeowners feed garden birds, which is nurturing increasing urban populations of feeder-using bird species, potentially sustaining up to 196 million birds. We should celebrate this, given that across the Channel in France urban birds, including Goldfinches, declined by 28 % between 1989 and 2019 (Fontaine et al., 2020).

Peregrines and Pigeons

After a short walk from Pulteney Bridge, I pass beneath North Parade Bridge. As the roar of traffic fades an aura of tranquility envelops me as I overlook the river’s serene western bankside, richly lined with mature trees and attractive waterside gardens. Adjoining the riverside is St John the Evangelist Church with its decorative Gothic-styled spire that dominates the city‘s skyline. The nature conservation charity, The Hawk and Owl Trust, erected a Peregrine Falcon nesting platform on the steeple in 2005, which became occupied the following year.

Peregrine Falcon numbers in the UK have recovered in recent decades, as the twin threat of human persecution and organochlorine pesticide poisoning has abated. While their screeching wail-like vocalizations are for me a true “call of the wild” evoking visions of remote mountains and rocky coastlines, Peregrines are now a familiar sight in the urban realm from London to Paris to New York, where constructed towers substitute for their traditional cliffside haunts. London alone has 25 nesting pairs (Goode, 2020). Given their rapid expansion into our urban landscape, at a population level at least, they are now in little need of additional intended assistance from us.

I often witness the Peregrines gruesomely dismembering their prey while surmounted on one of the church’s gargoyles. Lunch might occasionally include a Black-necked Grebe or Woodcock, prey species that indicate that the Peregrines are utilizing the city’s artificial light to hunt nocturnally, as both are unlikely to be flying through the city by day (Dixon & Drewitt, 2018).

It is the Feral Pigeon, however, which is the critical prey item sustaining Bath’s Peregrines and those in many other cities. The Feral Pigeon, a descendant of the relatively scarce coastal dwelling wild Rock Dove, is perhaps the most numerous and readily observable bird along the BRL, typically occupying the ledges of the bridges that span the river. While Feral Pigeons are sometimes disparagingly referred to as “flying rats”, viewing these resourceful species with fresh eyes can reveal much and even enhance a walk. Familiarity may have bred contempt for some but look again at their beautiful and varied plumage with its myriad of hues, including iridescent greens, bronzes, and purples on the neck, as well as exquisite wing patterns. As a fellow fan of the Feral Pigeon, Charles Darwin was the first to appreciate that human pigeon breeders (“Pigeon Fanciers” as they are known in the UK) have played the role of natural selection, artificially accelerating evolutionary processes to produce their amazing variety.

Gulls and House Sparrows

Turning my attention downstream from St John’s church, I look towards the contemporary Royal Mail Delivery Office building, which sits somewhat out of place amongst the splendor of Bath’s Georgian architecture. This incongruity is of no concern to the Lesser Black-backed Gulls that are nesting on its rooftop. Elsewhere Herring Gulls are also nesting on various commercial building rooftops adjoining the BRL. Within the City of Bath, there are estimated to be approximately 1,000 breeding pairs of Lesser Black-back Gulls and Herring Gulls combined (Rock, 2018). Both species have declined at their customary coastal nesting sites due to changes in the maritime environment, potentially linked to overfishing and climate change. Consequently, Herring and Lesser Black-backed gulls are now listed as birds of conservation concern, being Red and Amber listed, respectively.

Their adaptability to our urban realm, in which they are adept at scavenging on our waste (carefully timing their movements to coincide with our unintended food provisioning behaviors), has enabled both species to offset their coastal losses to some degree. The author Steven Lovatt (2020) describes the Herring Gulls of his hometown in South Wales as living “in a world of analogy in which the science block is a cliff, a bin lorry is a trawler, and a kebab is a herring”. Rooftop nesting gulls are also thought to be at an advantage over their more natural coastal-nesting counterparts because nesting space is not at such an extreme premium and due to greater dispersal of colonies, which reduces territorial aggression and vulnerability to predators, respectively (Goode, 2020). Gulls have also benefited from the UK’s Clean Air Act of 1956, which prohibited burning of waste at landfill sites (that now typically receive a soil-based cap at the end of each day), thus creating for them a considerable new feeding resource. Judging by the “don’t feed the gulls” signs pasted on all the city center bins, it seems that the council at least considers that these birds are in no need of help and indeed have attained pest status in the City.

While watching the gulls and the Peregrine, behind me I hear the unabating chirruping from a colony of House Sparrows occupying the small Spring Crescent housing estate. Here, the eaves and semi-cylindrical roof tiles of the 1930s style terraced housing provide convenient cavities under which the birds can nest. However, this quintessential species of the urban realm is declining in many European cities and has been added to the UK’s Red List. There are many potential reasons for the decline, one of which might be the reduced availability of cavity spaces suitable for nesting in many modern buildings (Chamberlain et.al., 2007).

Denizens of the River Wall — Grey Wagtails and Sand Martins

Despite suffering a decline nationally, Grey Wagtails also appear to be flourishing in the center of Bath, holding territory along the river every half kilometer where they nest in drainage pipes and cracks/crevices in the hard-engineered river walls. Contrary to what their name might suggest, the Grey Wagtail is a very attractive bird. The male’s black throat and slate grey back contrast with its yellow breast and under-tail, the latter being continually and flamboyantly wagged, behavior thought to be signaling vigilance. Males and females can often be spotted together in their customary territories, declaring their presence with their short metallic “tzeet tzeet” calls as they flit along the river walls foraging for their invertebrate prey.

While the river walls might superficially appear homogenous and hostile to life, given the time that Grey Wagtails expend foraging along them, clearly there is more to them than meets the eye. Closer examination reveals a more heterogeneous environment, provided by variation in wall materials (including sheet-piling, stone, and brick), material roughness, degradation (including cracks and crevices), sediment accumulation, inundation frequency, and aspect. This complexity provides niches for a variety of plant species, including woody shrubs, ferns, herbaceous ruderals, mosses, lichens, and algae, all of which support a range of invertebrates on which the Grey Wagtails (and sometimes Great Tits, Blue Tits, and House Sparrows) feast.

I admit that my avian expectations were somewhat subdued the first time I approached the most intensely urbanized section of the river that includes Churchill Bridge with its four-lane highway. This mostly treeless river section also abuts the city center bus and train stations. Yet, on closer inspection, this stretch is not without both architectural and wildlife interest. Regarding the former, just 20 m from the river edge is the Gothic-styled St James Railway Viaduct, the creation of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, one of Britain’s 19th-century giants of engineering. As to the latter, even along this superficially barren stretch of river, a small colony of Sand Martins has made it their home, nesting within river wall drainage pipes.

The Sand Martin is the smallest and most water-loving of the UK’s three hirundinids. While perhaps less visually striking than their close relatives – House Martins and Swallows – with their twisting aerobatics employed in pursuit of aerial plankton and incessant buzzing calls audible above the roar of traffic, these sociable migrants put on a magnificent show to those pedestrians crossing the bridge who register their presence. While originally, they would have exclusively used sandy riverbanks and cliffs for nesting, the Sand Martin is another breeding riverside bird species that has adapted to and benefited from the city’s human-made infrastructure.

Western Section of the BRL

Change in Breeding Bird Richness

Urban gradient analyses typically reveal an urban-rural transition in terms of biodiversity; biodiversity increasing with distance from the city center (McKinney, 2008). Although, as discussed, various charismatic and scarce species can be found near the center of Bath, in keeping with this theory breeding bird territory number and species richness both increase along the BRL from the center to the city’s western edge. This trend is probably not explained by increasing proximity to the countryside. While intuitively it might be assumed that the abundance and diversity of breeding bird species would be higher near to the countryside, in many farmed rural landscapes, numerous woodlands, hedgerows, and wetlands have been cleared, and herbicides and pesticides have greatly reduced the abundance of weed seeds and insect prey respectively, all of which has significantly negatively impacted on rural birdlife in the UK (Eaton et al., 2012). On the other hand, some urban habitats, particularly suburbs with large mature gardens and parks, can support important bird populations as discussed earlier. In the case of the BRL, the trend appears to be mostly correlated with increasing naturalization of the river corridor from the center to the city margins, as hard-engineered banksides and generally, more intensive adjoining land uses give way to natural banksides and mature riverside vegetation.

Migrant Warblers

As I continue my walk, certainly I register that the abundance of Chiffchaffs and Blackcaps accords with the urban gradient theory. These are the only two migrant warblers that commonly occur in towns and cities in the UK. Both species are typically associated with trees with dense shrubby understory, which is increasingly prevalent along the outer western section of the BRL. The Chiffchaff is named onomatopoeically for its uncomplicated “chiff chaff” song, while the song of the Blackcap often begins with a series of scratchy notes before it seemingly clears its throat and bursts into a delightful flute-like warble, giving it its nickname as the Northern Nightingale. Increasing numbers of Chiffchaffs and Blackcaps are deciding to overwinter in the UK rather than migrate to Africa, enabling them to seize the best territories earlier in spring (including in Germany) before the return of their migratory conspecifics. While warmer winters are likely to be driving this trend, as with Goldfinches, Blackcaps are also believed to be benefitting from the propensity of the British for feeding garden birds.

Occasionally I also hear the babbling scratchy song of the Reed Warbler, although these birds are likely to be passing through the city rather than establishing breeding territories. However, if herbaceous riparian habitat can be increased along the river edge, this quintessential songbird of UK wetlands that have been increasing in number nationally might become a welcome new addition to the city’s breeding bird assemblage.

Kingfishers

The Kingfisher is cherished as one of the most extravagantly colored of all the UK’s birds. For many, they seem almost too marvellously exotic to occur within our cities. Yet, with a watchful eye and sensitive ear they can be commonly encountered along the BRL and in many other towns and cities. I sometimes spot them sitting motionless on a branch at the water’s edge opposite the Lidl grocery store or even perched on the riverside fencing bounding the popular Elizabeth Park. Here, they are scanning the water for a Minnow, Stickleback, or even fry of a larger species, perhaps Roach, Bream, or Gudgeon. More often though, I glimpse a flash of iridescent azure blue as they dart by just above water level, sometimes with fish in mouth, an indication they have a nest nearby. Often their shrill whistle will give advanced warning of their approach.

Kingfisher numbers plummeted in the UK in the 1970s and 1980s, primarily due to river pollution, which disproportionately impacted populations within and downstream of industrial towns and cities. Their rapid decline led to them being placed on Schedule 1 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act. However, with improvements in water quality and hence their fish prey, numbers have bounced back. In the urban realm vertical earth banks, their preferred natural nesting sites, are at a premium, and so, as with the Grey Wagtail and Sand Martin, they also make use of river wall drainage pipes and other artificial cavities. I estimate that at least two territories are present along the entire ca. 5 km stretch, representing a healthy density of 0.4 breeding pairs per 1 km, compared with the species’ mean density of 0.1-0.3 pairs per 1 km (Libois, 1997).

Waterfowl & Weston Island

For a wetland habitat, the variety of waterfowl along the BRL is relatively limited and mostly consists of Mute Swans, Mallards, and Moorhens, although a few unexpected species can also be encountered. I often witness people being thrilled when they spot a Grey Heron along the river. These large and exquisitely beautiful birds stalk the river margins in search of fish or, according to one local resident, Brown Rats, which they capture with a lightning-fast strike of their dagger-like bills.

The digging of the Weston Cut in the early 1700s as part of the River Avon Navigation scheme created two parallel channels along a short stretch of the river and hence also an island known as Weston Island, or sometimes called Dutch Island after the mill workers from Holland and Flanders who came there to work. Although the island is now a busy bus depot, its wooded banksides have been retained and are a magnet for birdlife including Cormorants that can often be spotted roosting high-up in trees. With their long necks and hooked bills, Cormorants have a primitive, almost reptilian, appearance, creating an impressive spectacle, particularly when they strike their classic crucifix-like stance – body upright, wings held outstretched. While the expansion of Cormorants from coastal areas to inland waters is welcomed by most of the public, their popularity does not extend to some fishermen who take umbrage at the new competition brought by these supreme avian anglers.

Dismantled railway lines

During the 1960s approximately a third of the UK’s rail network was closed under what became known as the “Beeching Axe” (Richard Beeching was the author of the Government report recommending the closures). While the closures may be considered a lamentable loss of a sustainable transport option, many dismantled rail lines have developed into havens for wildlife, and some have been transformed into publicly accessible greenways. Among these is the Bristol and Bath Railway Path (BBRP), which intersects with the BRL near its western end. Wildlife corridor crossing points, or nodes, are often hotspots for biodiversity, as wildlife from two different habitats combine and can also disperse in multiple directions. The BRL-BBRP node is no exception, including the greatest variety and abundance of breeding birds along the entire surveyed river section. Here, I regularly hear the song of the Song Thrush, which is another of BRL’s Red-listed species. Although the attractiveness of its song can divide opinion, there are many, including myself, who find it amongst the most spellbinding of British bird songs. Song Thrushes possess an extensive repertoire of more than 100 phrases, each seemingly selected at random, and thus with each verse is the gift of surprise.

Conclusions

As I approach BRL’s western terminus, I hear the song of a Red-listed Skylark from a nearby field, signaling the limits of the city and transition to the countryside. Whether their quintessential song of summer and traditional farmland will continue to be heard from the margins of Bath in the years to come is in question due to the pressures of modern agriculture. While intensification of farming has destroyed or degraded a large proportion of the UK’s most important habitats and in turn led to a catastrophic loss of birdlife, some species are adapting to and even thriving in novel urban environments, including along the BRL. Indeed, a visitor keenly employing both their visual and audial senses can detect a surprising variety of species in just a short walk from the center of the city to its western edge.

Passing by St John’s Church in the heart of Bath, the screech of a Peregrine Falcon overhead raises the hairs on the back of my neck. Shortly after, standing on the vehicle-congested Churchill Bridge crossing, I involuntarily duck as Sand Martins streak by within inches of my head, twisting and turning in pursuit of their insect prey. A little further downstream and I have an awe-inspiring view of a brilliantly colored Kingfisher, perched on a riverside branch next to the carpark of a large grocery store. By shining a light on these and many other urban avian dramas, I have endeavored to reveal the amazing behavioral adaptations of birds to our highly human-modified world. In many cases, they demonstrate surprising tolerance of human disturbance and have become dependent upon us for their food, whether inadvertently or deliberately provisioned, as well as for refuge. At the same time, I hope that I have also shown that there are just as many opportunities for city-dwellers to connect with fabulous wildlife and, in particular, birdlife, as there are for their rural counterparts (if not more so).

Lincoln Garland

Bath

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr. Mike Wells (Biodiversity by Design), David Goode, and Karen Renshaw (Bath and North Somerset Council) for their kind and constructive comments.

References

Bakolis, I., Hammoud, R., Smythe, M., Gibbons, J., Davidson, N., Tognin, S. & Mechelli, A. (2018). Urban mind: using smartphone technologies to investigate the impact of nature on mental wellbeing in real time. Bioscience, 68, 134–145.

Clancy, C. & Ward, K. (2020). Auto-rewilding in post-industrial cities. Conservation & Society, 18, 126-136.

Dixon, N. & Drewitt, E.J.A. (2018). A 20-year study investigating the diet of Peregrines, Falco peregrinus, at an urban site in south-west England (1997–2017). Ornis Hungarica, 26, 177–187.

Eaton, M.A., Cuthbert, R., Dunn, E., Grice, P.V., Hall, C., Hayhow, D.B., Hearn R.D., Holt, C.A., Knipe, A., Marchant, J.H., Mavor, R., Moran, N.J., Mukhida, F., Musgrove, A.J., Noble, D.G., Oppel, S., Risely K., Stroud, D.A., Toms, M. & Wotton, S. (2012). The State of the UK’s Birds 2012. RSPB, BTO, WWT, CCW, NE, NIEA, SNH and JNCC, Sandy.

Fontaine B., Moussy C., Chiffard Carricaburu J., Dupuis J., Corolleur E., Schmaltz L., Lorrillière R., Loïs G., Gaudard C. (2020). Suivi Des Oiseaux Communs En France Résultats 2019 des programmes participatifs de suivi des oiseaux communs. MNHN- Centre d”Ecologie et des Sciences de la Conservation, LPO BirdLife France – Service Connaissance, Ministère de la Transition écologique et solidaire.

Goode, D. (2020). Recent examples of colonization and adaptation by birds in UK towns and cities. In: I. Douglas, P.M.L. Anderson, D. Goode, M.C. Houck, D. Maddox, H. Nagendra, & T. Puay Yok, (eds). The Routledge Handbook of Urban Ecology, pp. 439-451. Routledge, New York.

Harkness, J. (2019). Bird Therapy. Unbound, London.

Keynsham Angling Association (2021). River Avon. Retrieved from: http://www.keynsham-angling.co.uk/avon.htm

Libois, R. (1997). Kingfisher Alcedo atthis. In: E.J.M Hagemeijer & M.J. Blair (eds). The EBCC Atlas of European Breeding Birds: Their Distribution and Abundance, pp. 434-435. T&AD Poyser, London,

McKinney, M.L. (2006). Urbanization as a major cause of biotic homogenization. Biological Conservation, 127, 247–60.

Plummer, K.E., Risely, K., Toms, M.P. & Siriwardena, G.M. (2019). The composition of British bird communities is associated with long-term garden bird feeding. Nature Communications, 10, 2088.

Chamberlain, D.E., Toms, M.P., Cleary-McHarg, R. & Banks, A.N. (2007). House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) habitat use in urbanized landscapes. Journal of Ornithology, 148, 453-462.

Louv, R. (2017). Vitamin N: The Essential Guide to a Nature-Rich Life. Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill.

Lovatt, S. (2020). Birdsong in a Time of Silence. Penguin, London.

Ripmeester, E.A.P., Mulder, M., & Slabbekoorn, H. (2010). Habitat-dependent acoustic divergence affects playback response in urban and forest populations of the European blackbird. Behavioral Ecology, 21, 876–883.

Rock, P. (2018). Roof-Nesting Gulls in Bath and North East Somerset. Peter Rock.

Suri, J., Anderson, P.M., Charles-Dominique, T., Hellard, E. & Cumming, G.S. (2017). More than just a corridor: a suburban river catchment enhances bird functional diversity. Landscape and Urban Planning, 157, 331–342.

Tsing, (2019). The buck, the bull, and the dream of the stag: Some unexpected weeds of the Anthropocene. In: A. Lounel, E. Berglund, & T. Kallinen (eds). Dwelling in Political Landscapes: Contemporary Anthropological Perspectives, pp. 33-52. SKS, Helsinki.

Vaughan, I.P. & Ormerod, S.J. (2012). Large-scale, long-term trends in British river macroinvertebrates. Global Change Biology, 18. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02662.x

Williams, F. (2017). The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier, and More Creative. W.W. Norton & Company, New York.

About the Writer:

Lincoln Garland

Lincoln is Associate Director at Biodiversity by Design, an environmental consultancy in the UK. Lincoln has been working as an ecologist and eco-urbanist in consultancy, academia and for wildlife NGOs for more than 25 years. He has a particular interest in developing sustainable ecologically informed landscape-scale approaches to development and land management, with a particular emphasis on the urban realm and ecotourism. Contact Lincoln by email: [email protected]

Add a Comment

Join our conversation