Introduction

about the writer

Siobhán McQuaid

Siobhan is the Associate Director of Innovation at the Centre for Social Innovation in Trinity College Dublin where she heads up research and innovation activities under the themes of sustainability and resilience.

about the writer

Daniela Rizzi

Architect/urban planner (Faculty of Architecture & Urbanism of the University of Sao Paulo). Holds a doctoral degree in landscape architecture and planning (Technical University of Munich). Senior expert on Nature-based Solutions and Biodiversity at ICLEI Europe (ICLEI Europe).

Nature-based solutions provide an overarching framework embracing concepts and methodologies such as biodiversity net-gain, ecosystem-based adaptation, mitigation, environmental disaster risk reduction, green infrastructure and natural climate solutions to name a few. While much focus to date has been on the environmental or social benefits of nature-based solutions, less attention has been paid to their economic potential and their role in contributing towards more sustainable and just societies.

Indeed, modern economies are not generally build around nature and nature-based solutions — other than extracting from nature. The dire predictions of our climate changed future, now in many way already our present, tell us that this must change. Business as usual is not a prescription for human survival.

So, we ask:

— How do you see nature-based solutions contributing to the sustainable economy of the future?

— How do we go from nature-based solutions to a nature-based economy — where we work in harmony with nature — planning, growing, harnessing, harvesting and/or restoring natural resources in a sustainable way?

— What type of new jobs, new innovations, new enterprises might emerge from a nature-based economy and what are the challenges to uptake of such a concept globally?

These are some of the questions we asked respondents to consider as part of this TNOC virtual roundtable which forms part of a wider consultation on a new White Paper on the Nature-Based Economy.

Is this a discussion simply about assigning monetary value to nature? No, although in a monetized world this is part of the discussion. It is also about creating broad and inclusive discussions about nature and its benefits across the sectors of business, planning, engineering, science, conservation, and community. It is about recognizing the values of nature (in many dimensions) and firmly integrating these values in our economies.

We invite you to respond to the perspectives below or to read more and have your say: visit https://networknature.eu/consultation-draft-nature-based-economy-white-paper

about the writer

Ana Mitić-Radulović

Ana is a founder of the Centre for Experiments in Urban Studies (CEUS) from Belgrade, local coordinator of the CLEVER Cities project on urban regeneration via nature-based solutions, and PhD candidate in Spatial Planning.

Ana Mitić-Radulović

Post-pandemic recovery is the perfect occasion for spatial and urban planners to spark the conversation on grey-to-green transition of the public spaces and infrastructure, and for the governments to accept nature-based solutions and the accompanying economic activities, reskilling and upskilling of workers for green jobs, and adoption of policies which truly embrace nature-based economy.

Nature-based economy may be the critical window of opportunity

In the moment of absolutely obvious climate and environmental crisis — the summer of 2021 — the emerging concept of nature-based economy may be the critical window of opportunity for reversing the negative impacts of the current economic system, offering possible solutions for coping with the indispensable change ahead of us. Although nature-based solutions are perceived as enablers of “sustainable economic growth within the contexts of the climate change and biodiversity crises” (from Nature-Based Solutions to the Nature-Based Economy, a draft White Paper for Consultations, June 2021), today there are many reasons to question if “sustainable economic growth” is an oxymoron by itself. Nevertheless, the economy that “encompasses all production, exchange and consumption processes related to activities concerned with the protection, conservation, restoration and sustainable use of natural resources by consumers, industry and society at large” is by far the best option we can advocate for.

One can argue that economic system which is sustainable cannot impose perpetual accumulation of the surplus capital. The encouraging news is that younger generations (Y and Z, millennials and post-millennials) seem to be aware of it and ready to give up on it, in return for natural and environmental protection, more social justice, human dignity, and preserved mental health.

Many environmental activists from these generations also refrain from opportunistic and anthropocentric monetizing and pricing of ecosystem services and from considering nature as an asset, claiming that nature is invaluable. However, underlining the economic potential of nature-based solutions and natural capital is indeed critical for their timely uptake and upscaling by governments and the private sector, necessary for the positive environmental impact we desperately need.

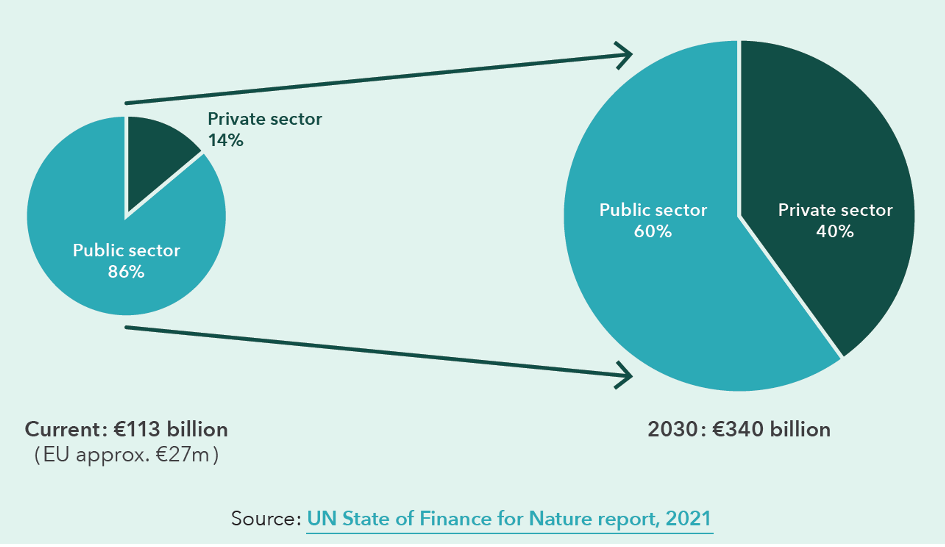

Efforts to promote a nature-based economy, in order to triple the investments in nature-based solutions by 2030, must be twofold. To reach the targeted increase of 120 billion euros of private nature-based investments — from the current 15 billion (UN Report on the State of Finance for Nature, 2021) — it is inevitable to communicate, collaborate and co-create with powerful and impactful stakeholders. This stream of action can bring technical shifts and quicker quantitative results, valuable for the current moment and the post-pandemic recovery actions. However, the profound value of nature-based economy and its potential for paradigm shift lies in the activities of the rising number of small, eco-social enterprises, that are not driven by necessarily creating the extra profit, but operating not-for-profit and environmentally responsible. This radical change of perception regarding satisfying, or even optimal business opportunities between the older generations (baby-boomers and Gen X) and the younger ones hopefully will bring qualitative, long-term transformation, serving as a cornerstone of restoration of our planet and protection of the organized human life on Earth that we know.

However, the profound value of nature-based economy and its potential for paradigm shift lies in the activities of the rising number of small, eco-social enterprises, that are not driven by necessarily creating the extra profit, but operating not-for-profit and environmentally responsible. This radical change of perception regarding satisfying, or even optimal business opportunities between the older generations (baby-boomers and Gen X) and the younger ones hopefully will bring qualitative, long-term transformation, serving as a cornerstone of restoration of our planet and protection of the organized human life on Earth that we know.

Social perspective of ecological transition is highly important: nature-based economy allows for new jobs, often less complex and more enjoyable, which can lead towards healthier and more just communities.

In the context of the Green Agenda for the Western Balkan, there is a strong potential for various sectors of nature-based enterprises in the EU Candidate Countries. Community landscape and biodiversity restoration has become fairly popular, as well as agritourism, regenerative agriculture and beekeeping. Demand for biomaterials for construction, green roofs and walls, as well as nature-based urban regeneration for urban green commons, green space management, and natural flood & surface water management are expected to develop in the near future. Challenges to uptake the nature-based economy in this area lie in the strong traditional engineering matrices and institutional impedance towards less technically-intensive, nature-based solutions.

Nevertheless, integrating urban perspective and the values of nature has never been more important. Post-pandemic recovery is the perfect occasion for spatial and urban planners to spark the conversation on grey-to-green transition of the public spaces and infrastructure, and for the governments to accept nature-based solutions and the accompanying economic activities, reskilling and upskilling of workers for green jobs, and adoption of policies which truly embrace nature-based economy.

about the writer

Domenico Vito

Domenico Vito, PhD engineer, works in European projects on air quality in Italy. He has been an observer of the Conferences of the Parties since 2015 – the year the Paris Agreement. Member of the Italian Society of Climate Sciences, he is active in various environmental networks and has been active participant in YOUNGO, the constituent of young people within the Framework Convention of Nations Unite.

Domenico Vito

NBS mitigate and increase land value in all the four dimensions of sustainability: environmental, social, economical, and participative.

The European Commission defines nature based solutions as: “Solutions that are inspired and supported by nature, which are cost-effective, simultaneously provide environmental, social and economic benefits and help build resilience.”

This definition contains several elements that resumes the main features and benefits related to nature based solutions. Nature based solutions (NBS) are forefront strategies for mitigation greenhouse gas emissions. Besides the best complex human technology, NBS collects with astonishing simplicity the benefits and the efficacy of act WITH nature rather than force nature against its rules. The impact of NBS is more holistic rather than reductionistic, as typical of the ones just technical or technological.

If these last ones are only acting on some of the sides of a problem that are intelligible by a model or a framework designed by humans, NBS are able to influence also ecological interactions, in a more integrated way. Compared to just a technological solution, NBS bring a more pronounced participatory dimension. If technology is usual proprietary, market-based, owned, held by a company or entity, nature-based solutions are collective, cooperative, and community-based. Just thinking to collective three planting. For these reasons, NBS can be inserted into a context not only for their mitigation function, but also to regenerate lands on a social and economical dimension.

A clear example of such assumptions stands in agroforestry solutions. Agroforestry pushes to integrate agriculture with the local landscapes and biodiversity profiles. It is based on the principle of ecological succession, which wants to recreate the same relationships among plants , trees and grasses that persist in a vital forest. The added value is that together also food species are inserted. A case study of a virtuose agroforesty, that also provide economical and social benefits is the project “Milano Porta Verde” (see the images).

In this project, 8 hectares of abandoned peri-urban land has been restored in collaboration with local association “Cascinet” and SoulFood Forest Farms Hub Italia”. The area has been planted by the volunteers and local neighbours of Parco della Vettabbia with the agroforesty technique and a Community Supported Agriculture initiative with a partner farmer has been started.

So beside the ecological restoration, this area acquired a social and food chain value.

Such an example is a clear demonstration of the second part of the definition of Nature Based Solutions, given that the EU that states “Such solutions bring more, and more diverse, nature and natural features and processes into cities, landscapes and seascapes, through locally adapted, resource-efficient and systemic interventions”.

Indeed, we can assume NBS mitigate and increase land value in all the four dimensions of sustainability: environmental, social, economical, and participative.

about the writer

Mamuka Gvilava

Mamuka Gvilava is environmental sustainability expert at GeoGraphic Ltd., based in Tbilisi, Georgia, experienced with cooperative projects in the Caucasus and Black Sea regions. His expertise includes environmental and strategic impact assessments, earth observations, green procurement, and nature-based solutions, latter gained within the European Connecting Nature project, co-founding the NBS UrbanByNature Caucasus hub together with the colleagues from the region.

Mamuka Gvilava

Nature-Based Economic development could indeed be the necessary, not merely sufficient condition for genuinely sustainable development. Any publicly supported project should be providing nature-based solution.

It is time to promote Nature-Based Development

A paradigm shift is required in development financing. Project appraisals by international (and national) funding institutions (IFIs) currently are based mostly on economic grounds and technical cost-benefit analysis after political funding decisions are made through country strategies etc., while nature, environment and even social factors are considered as second thoughts through so called environmental and social safeguards, such as environmental impact assessments and resettlement frameworks. As for health and safety, it is believed that they can be “controlled”.

In order for the development to become nature-based and contribute into nature-based economy, political and technical decision-making should be substituted by nature-based decision making: whenever the sectoral project is not nature-based as a priority, expect unexpected.

Luckily there is some experimentation by IFIs putting nature and environment at the front-end of the decision-making. A good example of this is the EBRD’s Green Cities initiative. There are plenty of examples even in my city of Tbilisi, Georgia, in the Caucasus, demonstrating how beneficial projects developed under the Tbilisi’s Green City Action Plan are, and how much damage can be self-inflicted when they are not.

Nature-Based Economic development could indeed be the necessary, not merely sufficient condition for genuinely sustainable development. In a sense, any project publicly supported should be providing nature-based solution.

Not convinced? Then just think how intrusion into bat habitats by transportation schemes and humans settlements resulted in our global pandemic stalemate . Who would think about bats seriously?

about the writer

Ellie Tonks

Ellie Tonks brings expertise in designing and delivering impact orientated climate innovation projects. As Programme Lead of EIT Climate-KIC’s Resilient Regions programme Ellie has worked with four European regions over the past 2 years, to design portfolios of climate-resilient adaptation innovations. Ellie has an MSc in Ecological Economics from The University of Edinburgh and a BSc in Ecology and Conservation from St Andrews University.

Ellie Tonks

At present, our economy does not favour a nature-based development agenda. But if a holistic case was built around the climate change adaptation and/or community health co-benefits, we could start to piece together a more compelling nature-based development case.

As an ecological economist the notion of a nature-based economy should come easily to me. However, it still sits oddly in my stomach. It sends me back to the conversations I would have with peers in ecology and conversation over my decision to study ecological economics. To discussions on their hesitation, resistance and worries towards concepts like “natural capital”, “green growth” or “ecosystem services”. The challenge with these concepts and narratives is the dichotomy between their sub-parts. When considering a response to the question of “How can nature-based solutions (NBS) provide the basis for a nature-based economy?” I am again confronted by the contract between what I associate as nature-based and as an economy. Therefore, I will try to address my discomfort head-on by setting out a vision for a nature-based economy, followed by why we must look past only the economic potential of NBS.

My vision for a (global) nature-based economy, is an economic system that is embedded within our social system, which is in turn is embedded within our ecological system. In other words, a nature-based economy is operating within our planetary boundaries, working mutually towards net-zero and resilience efforts. It is an economy in which the production and consumption of nature-based goods and services are used to meet the needs of the communities they serve, whilst regenerating and building resilience in the (eco)systems they rely on. For example, timber sustainably harvested from local mixed-species forest is used to substitute carbon intensive materials like cement or steel in construction efforts; meeting housing needs, whilst supporting local labour markets via the new jobs needed to process and build with wood. This example, however, sets out the fragility of the nature-based economy as it is an economy that must be deliberate and purposeful. The forests, for example, if not planted and managed to regenerate soils, promote biodiversity, and build resilience to future climate scenarios, can further lock-in vulnerabilities to our systems. As a result, the increased use of timber in construction, though it would realise quantifiable carbon benefits via carbon storage in wood-based produces in addition to providing new local economic opportunities, could jeopardise the ecological system in which it lives. Nature-based economies must therefore be designed deliberately.

The NBS that are the constitute elements of our nature-based economy can help realise whole system scale impacts, and not just economic benefits. Considering these systems scale benefits can support new business models and financing schemes, whilst creating the enabling conditions to grow new nature-based businesses and start-ups. For example, vacant and derelict land in cities represents a very physical opportunity for the nature-based economy to thrive within urban areas, however, the redevelopment of this land falls short in the development case when landowners hold off in the hope that land value will increase in the future. In other words, at present our economy is favouring a different development agenda. Whereas, if a holistic case was built around the climate change adaptation (e.g. water retention or urban cooling benefits) and/or community health (e.g. improved mental health and wellbeing or pollution reduction) co-benefits we could start to piece together a more compelling development case. This development case will never represent the full systems benefits of NBS (e.g. cultural, heritage or ecological values), however, it will support the growth of our nature-based economy, and in turn help the realisation of these multifaceted benefits.

In summary, we need to be purposeful when designing both the NBS that constitute our future nature-based economies, and the future nature-based economy itself. Both need to be net-zero, resilience building, and regenerative in their design.

about the writer

Isaac Mugumbule

Isaac Luwaga Mugumbule is the Head of Landscaping at the Kampala Capital City Authority. He holds a degree in Architecture with specialized training in green infrastructure management and urban design and has 12 years experience in the built environment and urban landscape. He led Kampala’s first urban forestry audit and development of an urban green infrastructure ordinance.

about the writer

Rhoda Gwayinga

Rhoda Gwayinga is a Supervisor Risk Management at Kampala Capital City Authority(KCCA). She holds a bachelor’s degree in Economics, a post graduate diploma in financial management and a certified fraud examiner. Rhoda has 13 years’ experience in risk management and has worked in the banking sector, international NGO and with government entity(KCCA)

Isaac Mugumbule and Rhoda Gwayinga

Governments, policy makers, experts and private sector need to collaborate and develop Nature-based economic indicators. These could explore factors like urban forestry cover, air quality, blue infrastructure, population growth, green technology. NbE indicators would then be used as a basis for driving key economic policy decisions as opposed to the norm.

The concept of Nature-based economy (NbE) is new to the City of Kampala and to most cities across the globe. In the past, we have had a lot of dialogue around Nature-based Solutions (NbS) and Impacts of Climate change on a country’s economy but never on the same platform. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), it defines Nature-based Solutions (NbS) as “actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural or modified ecosystems, that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits”. This umbrella of NbS creates the opportunity to incorporate other urban actors in the discussion on NbE.

Kampala City is the Capital City of Uganda and is located next to one of Africa’s largest natural asset, Lake Victoria, the largest lake in Africa. Another major natural asset in Uganda is the longest river in Africa, River Nile, which also originates from Lake Victoria. Unlike most cities, Kampala has two population figures, that is a night population (residents) of 1.65 million people and day-time population of 4.0 million people (UBOS, 2019). This large disparity in the two population figures shows the urbanization pressures this city faces. However, if the city fails to protect the ecosystem around Lake Victoria, then this will have devastating effects not only on the economies of countries within the Lake Victoria basin but also the countries served by the River Nile all the way up to Egypt in Northern Africa. It should be noted that these two large natural assets have been critical in guiding economic discussions within Africa and have led to the formation of key economic groups, that is the East Africa Community (EAC) which consists of six partner states and the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) which consists of eleven partner states. More than half the global population now lives in towns and cities.

By the year 2050, UN-Habitat research projects that the figure will rise to two-thirds. According to the Kampala Physical Development Plan (KPDP), it is projected that by 2040, a population of 10 million people will be living in Kampala. In order to mitigate the pressures of urbanization, Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) developed a 5-year strategic plan (2020-2025) aimed at addressing the challenges of urbanization in a holistic approach. This strategy incorporated the KPDP, Disaster Risk and Climate Resilience strategy, the Kampala Drainage Masterplan and the Kampala Climate Change Action Plan (KCCAP). According to the Disaster Risk Resilience strategy, an integrated approach has been set out in managing disasters in the city. This includes avoiding creating risks, reducing existing risks, responding more efficiently to disasters and mitigating the effects of climate and building climate resilience. The resilience strategy will inform KCCA’s Investment planning and operations for the strategic plan, as well as sectoral plans and Investments. KCCAP aims at mainstreaming climate change response in all city services in order to put the city on a low carbon development path.

NbE essentially looks at how cities will effectively utilize the existing resources in a sustainable way while building resilience and maintaining a balanced ecosystem amidst the threat of climate change. Governments, policy makers, experts and private sector need to collaborate and develop Nature-based economic indicators. These could explore factors like urban forestry cover, air quality, blue infrastructure, population growth, green technology. NbE indicators would then be used as a basis for driving key economic policy decisions as opposed to the norm. All governments need to closely monitor these NbE indicators and any negative change should trigger a warning that will translate to an appropriate response to mitigate the looming crisis.

about the writer

Audrey Timm

Dr Audrey Timm is a horticultural scientist specialised in ornamental horticulture. Since joining International Association of Horticultural Producers (AIPH) as Technical Advisor in early 2019, Audrey leads their Green City initiative with the purpose of increasing the quality and quantity of living green in urban environments, and of nurturing a strategic shift in city form and function.

Audrey Timm

When nature-based-solutions become an integral part of city infrastructure, nature becomes woven into the economic support network, providing new business opportunities, jobs and income-generating activities across a broad spectrum of the population.

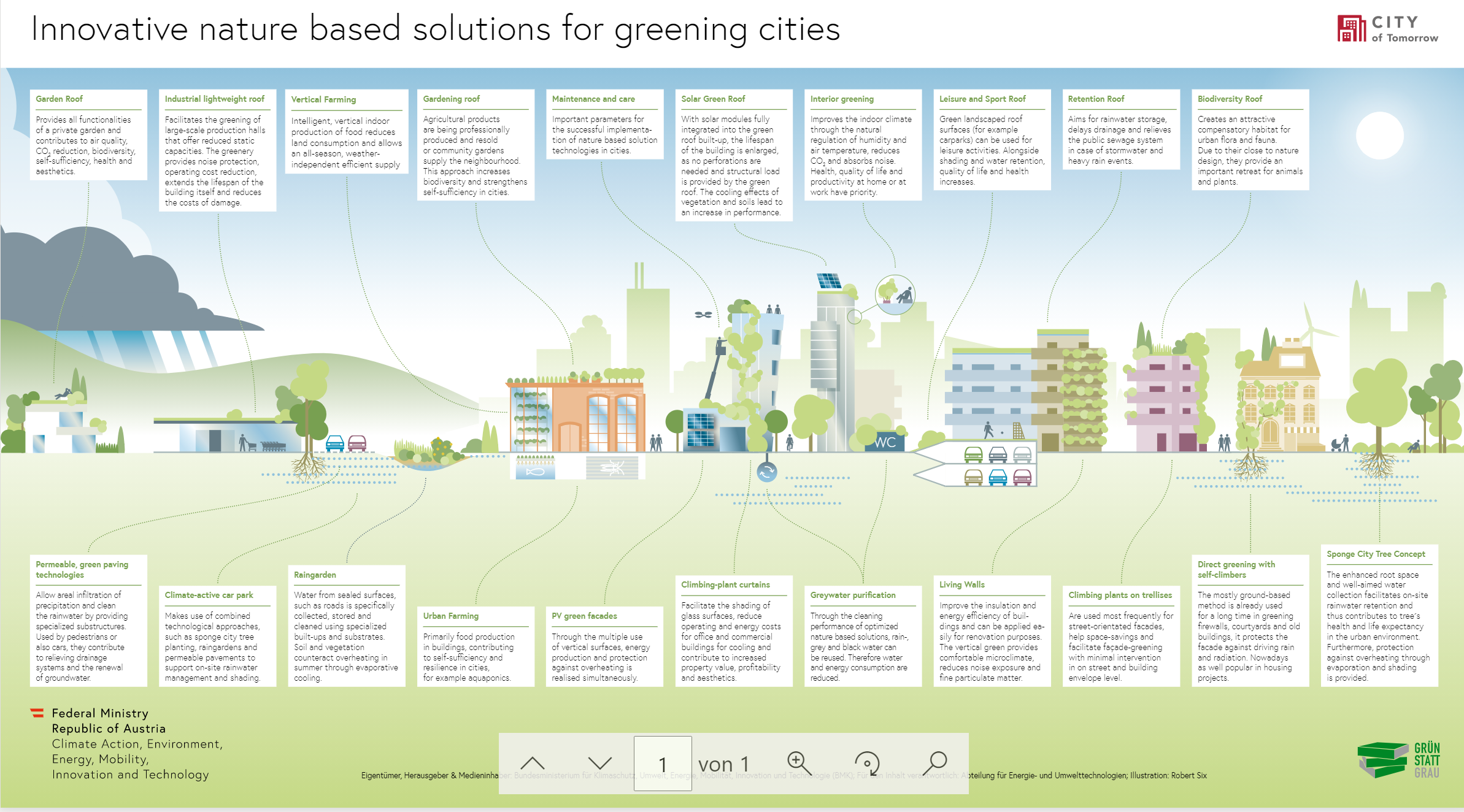

The key to answering this question is in the word “solutions”. Nature-based-solutions need to solve a problem that challenges our quality of life in a way that makes them indispensable to our future.

In a broad conservation context, nature-based solutions are very much about restoring natural systems to recover from or avert disasters. In a city context, we need to emulate natural systems. We need to understand how they work, and how this therefore provides the solution that we seek.

For example, trees capture rainfall, slow it down, and drip around the canopy fringe to support their own growth. By doing this trees protect the soil, both from reducing the impact of individual droplets that could compact the soil, and by preventing erosion from flooding. Leaf texture plays a role in rainfall interception, as does plant shape. Nature-based solutions that aim to prevent flooding need to recognise this knowledge and use it to their advantage. Replacing hard, impermeable surfaces with planted and semi-permeable space doesn’t stop heavy rainfall incidents occurring. It stops them from being a problem. The same is true with planted swales that are designed correctly and have suitable plants established. Other examples include hedges to buffer against noise pollution, green roofs and walls as thermal insulation, vegetation to attenuate local air pollution, and trees and greenery to reduce the urban heat island effect. All of these require an understanding of the characteristics of plants that deliver specific solutions, and of the selection and placement of plants in relation to the urban fabric to achieve success.

Nature-based solutions in the urban environment go beyond simply providing an opportunity for reconnecting people and nature. They work in tandem with the built infrastructure, providing solutions that hard, engineered systems cannot deliver on their own. Implementing successful nature-based solutions is driven not only by knowledge, but by an understanding of how the knowledge contributes to the solution. From this perspective, no single sector can drive a nature-based economy. When nature-based solutions become an integral part of city infrastructure, nature becomes woven into the economic support network, providing new business opportunities, jobs, and income-generating activities across a broad spectrum of the population. Nature-based solutions cannot be motivated as part of the future of our city economies because nature needs our help; they are part of the economy because we need to mobilise the help of nature for our future.

about the writer

Rupesh Madlani

Rupesh spent a decade at Lehman Brothers and Barclays in equity research in sustainability and clean technology, ranking first in the Institutional Investor survey. Prior to this, Rupesh worked at PwC in the corporate finance practice. Rupesh has a degree in economics from the London School of Economics, is a chartered accountant and Freeman of the City of London. Rupesh is an expert reviewer in various publications with the World Economic Forum, the OECD, Prince of Wales Sustainability unit and the United Nations relating to sustainable development.

about the writer

Emre Eren

Emre has acquired experience in multiple projects at BwB working on the innovative finance structures required to fund projects, covering a wide list of sustainability linked subjects including energy, biodiversity, debt restructuring, circularity, green infrastructure and retrofit. Emre holds a BSc Hons Accounting and Finance degree from LSE having achieved a First-Class Honours. He is also an entrepreneur having established his own start-up.

Rupesh Madlani and Emre Eren

The extent to which nature-based solutions can provide a basis for a nature-based economy depends on the coinciding policies, frameworks, and mechanisms implemented. With the correct policies that address barriers and drive enabling factors, nature-based solutions include such a wide variation of projects that they provide a strong foundation to achieve a nature-based economy.

Nature-based solutions can only provide the framework and foundations of a nature-based economy if these solutions are accompanied by strong overarching policy recommendations that ensure barriers to scale are addressed, and enabling factors are enhanced. For example, in order to have a nature-based economy, nature-based solutions such as urban forestry and others that provide carbon sequestration need to be scaled immensely. However, these nature-based solutions find it difficult to attract private investors due to a lack of direct revenue streams that can be used to provide economic incentives to the private sector. Hence, nature-based solutions such as urban forestry need to be accompanied with policy amendments that address barriers such as providing more confidence in future revenue streams through greater certainty around carbon prices through, for example, a minimum price policy or framework for carbon. These policy amendments will increase confidence in commercially viable models and cash flows for nature-based solutions which in turn can help achieve scale and a transition to a nature-based economy.

Also, in addition to policy amendments that address barriers such as long-term revenue streams and commercially viable models, instruments and mechanisms that enhance the enabling factors at scale and incentivise nature-based solutions are essential. For example, BwB has worked closely with developing countries to develop and utilise KPI bonds (as well as SDG bonds found here: https://www.bwbuk.org/post/bwb-partners-with-undp-to-issue-first-sdg-bond-for-uzbekistan) that incentivise proceeds to be used for country-specific nature-based solutions that prioritise issues in each country. These KPI bonds, alongside a robust MRV (Monitoring, Reporting and Verification) mechanism allow for NBS projects to be implemented at scale given the significant coupon and principal reductions that can be achieved based on targets, hence the wider adoption of these instruments can have a more notable impact in terms of a nature-based economy. Another key enabling factor for achieving a nature-based economy will be mechanisms or frameworks put in place that correctly value NBS. BwB has developed a centralised mechanism named Green Neighbourhoods as a Service (found here: https://www.bwbuk.org/post/green-neighbourhoods-as-a-service) which utilises the co-benefits that arise from these projects to address the mismatch between ownership of the capital spend and of the value of benefits, tackle the fragmentation issue, overcome barriers to entry, allow aggregation of projects and matching of different types of finance that will be needed. Such a centralised mechanism that brings change on a neighbourhood-by-neighbourhood basis in the long-term can have a significant impact in achieving a nature-based economy.

Furthermore, in order for nature-based solutions to provide the basis for a nature-based economy, there needs to be greater transparency around the frameworks used to identify nature-based activities and ensure funder capital is directed to the correct coinciding projects. For example, the IUCN Global Standard provides clear parameters for defining nature-based solutions and a common framework to help benchmark progress. This is essential to increase the scale and impact of the NBS approach, prevent unanticipated negative outcomes or misuse, and help funding agencies, policy makers, and other stakeholders assess the effectiveness of interventions. This will allow financers to invest in NBS with confidence that the standard provides a benchmark, minimising risks and adding assurance. Such a standard also allows for the wider stakeholder groups in society to get involved and engage with the governance structure of the standard.

In conclusion, the extent to which nature-based solutions can provide a basis for a nature-based economy depends on the coinciding policies, frameworks, and mechanisms implemented. With the correct policies that address barriers and drive enabling factors, nature-based solutions include such a wide variation of projects (including green and blue infrastructure, ecosystem services, ecosystem-based adaptation, ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction, blue-green infrastructure, low-impact development, best management practices, water-sensitive urban design, sustainable urban drainage systems and ecological engineering), that they provide a strong foundation to achieve a nature based economy, but not standalone.

about the writer

Susanne Formanek

Susanne Formanek is managing director of the innovation laboratory GRÜNSTATTGRAU, initiator of many projects in the green building sector and since 2017 president of IBO, the Austrian Institute for Building Biology and Ecology. This is an independent, non-profit, scientific association that researches the interactions between humans, buildings and the environment. She graduated from the University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences in Vienna in the field of forestry and timber management.

Susanne Formanek

Working in harmony with nature means to overcome lack of understanding that maintenance is essential, and that the costs of maintenance need to be budgeted for.

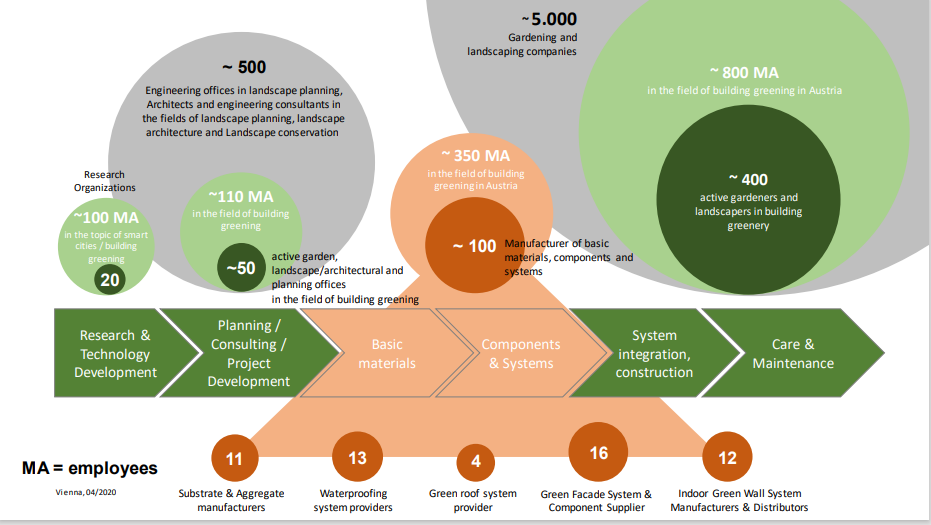

Based on our GREENMARKETREPORT we know today that 38% of the surveyed companies were founded in the past 10 years. If every other newly constructed building is fitted with a green roof we would generate 33.000 new green jobs in Austria. This means: for every 8,000 m² of additional green roof area, 10 new jobs are created.

Market potential

The direct value chain of greening buildings just in Austria includes 550 companies and 1200 jobs, whilst the sector is quiet young and has great potential to grow. The branch demands productive interdisciplinary cooperation within the market and between other branches. Therefore the greening buildings and NBS sector provides value for other sectors as well as innovations such as the sectors of construction, circular economy, additive manufacturing, digitalisation etc.

Currently, mainly small and medium-sized companies are active in this country along the entire value chain, from technology development and planning to the manufacture of components, execution and maintenance. The industry is also characterized by a high degree of innovation “made in Austria”: The targeted combination of green roofs with other technologies, such as PV, further enhances their impact. These include, for example, solar green roofs in which the cooling effect of the plants boosts the performance of photovoltaics, or the use and purification of gray and service water on roofs.

Wertschöpfungskette AGMR.pdf

Value enhancement

Traditional grey buildings are exposed to all kinds of weather conditions without any protection and need to be renovated from time to time. Greening buildings in comparison acts as a protection shield against weathering and reduces renovation and maintenance costs. Green and living walls and green roofs provide a natural sun screen and insulation. This saves on air conditioning and less energy is used. Green roofs are low-cost in maintenance and long-lasting. Compared to traditional flat roofs, the service life of the roof sealing of a green roof is extended by at least 10 years.

Green infrastructure in and around properties increases the value of the property and the neighbourhood by an average of 4-8%. Improved living conditions lead to higher satisfaction of the habitants are convincing reasons to inhabit and stay in greener quarters. Environmental improvements such as better air quality and lower temperatures lead to a healthier population. This increases life expectancy of people but also minimizes sick days leading to reduced costs for sick leave for companies.

From nature-based solutions to a nature-based economy

Working in harmony with nature means to overcome lack of understanding that maintenance is essential, and that the costs of maintenance need to be budgeted for. Our funding program “City of tomorrow” promotes demonstration buildings, and monitoring always playing an important role. Thus, growth performance, vitality of the plant and nature and care and Maintenance can be compared with each other and has a consistency. We are raising awareness by realizing these best practice projects.

The multiple benefits of this nature-based asset can be realised, when a long-term strategy is existing. High quality execution of green infrastructure is also very important. For this reason we have developed standards and new qualification program in Austria, which include maintenance concepts in which we compare the overall costs to the expected benefits and advantages.

Our Biodiversity Strategy Austria 2020+ aims to conserve biodiversity in Austria, to stem the loss of species, genetic diversity and habitats and to minimize the causes of threats. The Biodiversity Strategy Austria 2020+ defines goals and measures for the conservation of biodiversity in Austria. These are based on the international objectives set out in the Convention on Biological Diversity and on those of the European Union.

And we are faced by growing ecomplexity in construction — now also including the interfaces to Bulding Information Modelling. Our programme “klima-aktiv building and renovation” implies energy efficiency, ecological quality, comfort and execution quality.

Finally our innovation lab GRÜNSTATTGRAU is an instrument of the ministry and funded within City of Tomorrow, and owned by the association of green roofs and green walls in Austria. This is the holistic competence center in Austria for greening buildings focuses especially on the comprehensive benefits of green roofs, living walls and indoor greening. Green infrastructure on buildings provides a broad range of environmental and social benefits and impacts on the building itself, which have great economic value and lead to a sustainable economy.

Green finance

In recent years, the term “green finance” has replaced the term “environmental finance” and defines a spectrum of financial approaches and instruments for environmental and climate protection, for adapting to climate change and for compensation environmental and climate damage. In terms of greening innovations, this approach is important because greening buildings not only benefits the owners, the direct users, but also the surrounding urban landscape and neighbourhood. Therefore, a different financial approach or perspective is needed for climate change measures such as greening buildings. Our program Green Finance 2021 by the “Klima und Energiefond” supports companies and municipalities/cities in carrying out a profitability calculation for planned projects. Innovative solutions and technologies from Austria thus quickly find their way into the domestic and often also international market.

Further information: eia_03_18_englisch_v03k.pdf

Further information: eia_03_18_englisch_v03k.pdf

bmk_InStBegr_Folder_nur-de (nachhaltigwirtschaften.at)

about the writer

Hans Müller

Master gardener and managing director. Owner of three agricultural production horticultural businesses and managing partner of Helix Pflanzen GmbH and Helix Pflanzensysteme GmbH. Vertical greening has been part of Hans Müller’s entire horticultural career. For about 15 years there has been a clear strategic corporate orientation to harness ecosystem services from vertical vegetation. Hans Müller and the company Helix Pflanzen GmbH have since worked in various national and international research consortia. In 2017, Hans Müller received the Taspo Award in gold as horticultural entrepreneur of the year 2017

Hans Müller

There are two levels of developments concerning a nature-based economy: (1) The NBE (Nature based Enterprise) Startups focusing on NBS; (2) Classic / traditional companies transferring towards an NBE. Both are important and for both I see economic advantages.

How can nature-based solutions (NBS) provide the basis for a nature-based economy?

One important key is monetizing the ecosystem services provided by nature. Without doing this, without giving an economic value to NBS there will be no significant and natural development for a nature- based economy.

Why is that?

Economic processes are based on the principle of cost and value of goods and services. Also, the principle of opportunities and risks.

What is the cost of pollution, what is the cost of missing green, missing trees and shrubs in urban areas? It just started to price the Co2 emissions. It is well known, that taxes on cars per year does not match the hidden cost of pollution and health risk on man per year and car. This need to change!

The other perspective: Studies have shown that the timespan patients stay in hospitals is shorter, when their hospital room facing into a lush green space. Patients locking into a Park or green area shortens their stay in hospital and the heath system safes money. This money should be made available to the owner of the Park for their maintenance budget.

Politics has to have a close look at that and need to prepare fair rules to enable the development of nature- based economy. To value, the cost of pollution and the value of ecosystem services of NBS need to get visible, and the bill needs to be paid. Then there will be budgets for NBS and also for the transformation towards an NBE

Market- based mechanism will then boost the nature-based economy.

Maybe this sounds too simple for you — you are right — it is not. It is far more complicated, I know. Anyway, the roles to the economic playground needs to be sharpened by politics.

To me, there are two levels of developments concerning a nature-based economy

- The NBE (Nature based Enterprise) Startups focusing on NBS

- Classic / traditional companies transferring towards an NBE

Both are important and for both I see economic advantages.

To me, there are already many signs towards a nature-based economy:

Public demand for NBS is visible, and not many companies can provide goods and services at the moment. The public awareness towards the climate crises and lack of biodiversity leads to NBS. Cooperate Financing will get harder without a CSR report including environmental aspects. The Fridays for future generation is highly sensible for the eco aspects, and they are the future employees and CEOs.

Let’s get started and monetize Eco System services on a wide scale!

about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

David Maddox

I am thrilled that some businesses are advancing in this conversation about sustainability. But we need more. We need everyone — all businesses and all people — to be part of the change, which will require sacrifice.

I worked for The Nature Conservancy in the late 1980s, and at that time significant money came to TNC from large corporate donations, with as car companies. A former president of the organization was asked if it was appropriate to use money to conserve land that was “tainted” by environmental damage by the donor in other sectors of the economy, especially extractive industries. He was famous for his answer, in American slang: “Tainted money? T’ain’t enough”. His meaning was that if we did good with the money, then its provenance was not a concern.

I and others were uncomfortable with this approach.

Our — meaning the world’s — issues of sustainability, resilience, livability, and social justice are so vast that the answers cannot be found in corporations donating to green causes, thus providing political cover. This is greenwashing. A cover-up that simply happens to look green. Buried deep in our problem is that we are better at appearing to be green-virtuous that making fundamental changes that often are inconvenient or seem to “cost more”. This is for regular people too, not just businesses. Recycling comes to mind, when we recycle at higher rates, but consume even faster. We get a bigger car that has marginally better gas efficiency, but we drive more and don’t use public transportation. We buy organic food without worry that is was grown halfway around the world.

These problems have roots in economies across sectors, from businesses themselves to people (i.e., consumers). Businesses, people, and governments will have to demand more of each other.

In the global north, where economies are largely grounded in an unsustainable demand for growth, we need to reassess our values, and both businesses and regular people will have to adapt and sacrifice by putting effort and money into change. Governments must help by creating real incentives to reward our efforts and regulations (such as planning and zoning codes and requirements for nature-based solutions) with bite.

In the global south we face a different but related challenge. It is that around the world millions of people need their standard of living raised. This will require greater consumption of food and energy, and will result in increases in factors that cause climate change. Many of us who read TNOC — most, I imagine — believe that raising living standards for the world’s underserved is moral, just, and right. Will we in the global north be prepared to sacrifice for this just cause? Maybe. Maybe not. For their part, all these new cities in the south are an opportunity to not repeat the same planning mistakes of current cities. We’ll need imagination, and resist the temptation of the easy solution that has a big development company (often from the north) get paid to recreate an old-fashioned solution.

I was one of several editors on a book on about sustainability. It contained a chapter by a journalist in Karachi, who wrote that the debates about sustainability and economies that occur in London and New York and Paris seem to occur on another planet, with no relevance to a city in which drinking water is sold on the street by organized crime. I shared the stage once with an indigenous (Mapuche) and women’s rights activist from Patagonia, hoc was also part of the aforementioned book. She recounted how she was challenged in Europe by a person with one child, who said the five children that the activist had were “immoral and unsustainable”. The activist responded that her five children in Patagonia consumed many fewer resources than the accusor’s one in Europe.

Fair enough. These are conversations that require action and often sacrifice. But whose sacrifice? They will be difficult conversations. They will require a willingness to acknowledge our own roles in the problems that face us.

For me, several imperatives are clear, although I am not sure people are ready for the political battles they would require. (I mean, we cannot seem to even agree that getting a vaccine is a good idea during a global heath crisis.)

- We need to abandon economic growth as a de-facto good

- We need to root out greenwashing

- We need to accept the idea that sustainability will cost all of us something

- We need to understand and act on (i.e., be responsible for) the true environmental costs and “footprint” of our actions

- Nature-based solutions should be required of all companies (and individuals when it makes sense), not just as a region-wide goal; and they can’t just be another aspect of greenwashing

- We must achieve not carbon neutrality, but a carbon negative; this is the only way to sustain increased livability in developing nations

I am thrilled that some businesses are advancing in this conversation about sustainability. But we need more. We need everyone — all businesses and all people — to be part of the movement.

about the writer

Cecilia Herzog

Cecilia Polacow Herzog is an urban landscape planner, retired professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. She is an activist, being one of the pioneers to advocate to apply science into real urban planning, projects, and interventions to increase biodiversity and ecosystem services in Brazilian cities.

Cecilia Herzog

Brazilian cities are still introducing nature-based solutions as demonstration projects on a slow pace. The landscape transformation must gain scale urgently, bringing nature to all possible places. Taking out cars, planting trees and opening spaces for people close to regenerated urban nature, creating new and sustainable businesses and jobs.

Let’s invest in human incredible capacity and imagination to regenerate planet Earth

Yes, we urgently must adopt a nature-based economy worldwide. We need a radical shift in the indicators we measure value and wealth, and switch to an ecological economy. Georgescu-Roegen, Daly, Elkington, Klein, McKibben, Piketty, Raworth, Mazzucato, among so many others have been proposing and advocating for this essential transformation during the last century, especially in the last decades. The collapse we are now was foreseeable long time ago. The present trigger is climate emergency showing that our environmental, social, and cultural predatory economy led us in a wrong direction. Countless concomitant climate impacts worldwide are happening. It is undeniable that time urges to transition to a new nature-based economy that fits in the planetary boundaries and reverse the abyssal social disparities, besides respecting social-cultural, ethnic, and gender distinctiveness of all people.

Climate is global and is affecting rich and poor countries, real people in the real world, destroying our biosphere on an unthinkable speed.

New green deals emerging in wealthy countries must take a tangible turn when NATURE and PEOPLE must be THE PRIORITY!

Brazil has a huge role to play in this scenario, where the AMAZON and other precious biomes collapse must be taken extremely seriously. At the Federal level things are going from bad to worse, to unimaginable catastrophic magnitude.

At city level, Brazilian cities are still introducing nature-based solutions as demonstration projects at a slow pace. The landscape transformation must gain scale urgently, bringing nature to all possible places. Taking out cars, planting trees and opening spaces for people close to regenerated urban nature, creating new and sustainable businesses and jobs.

Ecological education is key to everyone, introducing nature-based solutions in urban areas is an excellent way to enable urbanites to learn about ecological processes and our intrinsic relationship with all forms of life and how ecosystem services are essential to our own survival. We are in the decade of biodiversity, the protection of remnants and regeneration of degraded areas must be prioritized in all scales: gardens, ecosystems, biomes…

Multilateral banks are already focusing on NbS, inducing their investments to projects that are environmentally and socially oriented (e.g. World Bank, IDB), as well as the World Economic Forum. Many corporations are also at high risk, most of them depend on nature to produce their goods, sell their services and so on, and many are taking the questions seriously (e.g. insurance companies).

The concentration of wealth in the hands of very few people while the vast majority of the humanity tries to survive until the next meal, has to be addressed. In my view, there is no way we will overcome the disaster unless the economy, politics, and decision makers find a way to redistribute capital in a fair way, so every person on earth will be able to be concerned with our collective good and invest on nature-based solutions.

The transformation of the way the economy functions must lead to innovative and creative ways to regenerate nature wherever possible, using our incredible capacity and imagination here on our planet Earth. For this to be achievable, it is also urgent to enlighten people to value nature (biodiversity, ecosystems, clean water bodies, oceans…) more than exploring other planets and buying superfluous consumer goods. We must innovate, educate, and create new jobs that restores ecosystems; produce heathy foods; build and prepare cities to be resilient to climate impacts; shift to clean and active mobility in comfortable and safe ways; adopt (incentivize) renewable energy (and divest on fossil fuel); value and invest in local production; besides developing technologies that enables recover ecological functions that are desperately needed.

I believe we will see a shift on the way we relate to nature so we can remain living on this wonderful planet that is our only home. This has been said so many times that all humans should be eager to contribute to enhance all forms of life, protect existent ecosystems (terrestrial an aquatic) and be trained to live and work on this new regenerative paradigm of nature-based economy.

about the writer

Naomi Tsur

Naomi Tsur is Founder and Chair of the Israel Urban Forum, Chair of the Jerusalem Green Fund, Founder and Head of Green Pilgrim Jerusalem, and served a term as Deputy Mayor of Jerusalem, responsible for planning and the environment.

Naomi Tsur

There is no doubt that nature-based solutions contribute to the economy, but that does not necessarily mean that they can provide the basis for a complete economic framework. But nature in and around cities is gradually earning the right to be recognized as a very significant layer of infrastructure, along with water and food (agriculture). This is, effectively, the infrastructure that gives us life.

It has taken many decades for the issue of climate change to gain center stage in the global conversation, and even now that has been achieved, who knows how much longer it will take for the necessary steps to be taken to re-establish the balance between man and nature that is essential for our civilization to survive?

As the conversation develops, so do the misunderstandings that arise in the course of any discussion. Particularly acerbic is the superfluous argument between the teams set on protecting biodiversity (the root problem), and the teams working to achieve the goal of zero emissions. These last are often so focused on their task, that they sometimes seem to forget why they are doing it.

Meanwhile nature in and around cities, historically viewed as the “leftovers” of urban development, is gradually earning the right to be recognized as a very significant layer of infrastructure, along with water and food (agriculture). This is, effectively, the infrastructure that gives us life.

Parallel to the painfully slow increase in awareness of the simple fact that it is we who need nature and not the reverse, it is now understood that nature itself can provide some of the best means of defense for the other kinds of infrastructure that we hold so dear, such as transport systems, buildings of all kinds, in short our urban fabric.

I have been following the course of urban and peri-urban nature for the last 25 years, and it has been, and continues to be a fascinating journey. In my own city, Jerusalem, I am familiar with the details of every step in the journey, but I see similar processes in many other cities around the world. These are the steps I have followed closely in Jerusalem:

- The discovery of natural areas within cities that have not been built on or developed as neatly sculpted gardens.

- The understanding that these areas have cultural, educational and recreational value for the local urban community.

- The realization that these areas have been guardians of various species, and indeed enabled their survival.

- The appreciation that nature within the city can be part of the broader picture, in that ecological corridors do not end at the city boundary, but in fact run through the city, a reality that needs to be incorporated into urban planning.

- The grasp of the potential contribution of urban nature to mitigation of and adaptation to climate change. For example, we all know the importance of trees in our cities, the contribution of well-managed community gardens to the restoration of damaged habitats and local food-growing is well-known, and many cities have used natural areas to protect their drainage basins from catastrophic flooding.

- More recently, the value of nature-based solutions has gained greater recognition, along with the understanding that such “solutions” can have enormous economic value, especially when it comes to preventing floods, ensuring that run-off from rainwater is safely filtered before flowing back into underground water reserves, or harvesting rainwater for use in drier seasons, in the case of arid climates.

There is no doubt that nature-based solutions contribute to the economy, but that does not necessarily mean that they can provide the basis for a complete economic framework. If I take as an example one of the famous case studies from Jerusalem, the Gazelle Valley Park, I believe it is entirely possible to quantify the economic benefit of the initiative, independent of the clear social and environmental benefits.

- It is a nature park, designed to cater for the herd of gazelles that live there. There are therefore no electric lighting installations, so as not to disturb the gazelles’ natural cycle. Result: a lot of money saved.

- It is a nature park, so the gardening required is minimal and low maintenance. Result: a lot of money saved.

- The park is designed as part of the Soreq drainage basin. The lakes in the park are formed from winter rainfall, and supplemented in summer with tertiary treated sewage water. No tap water is used. Result: a lot of money saved.

- The park covers 65 acres, in the heart of the city. There is enormous demand for housing near the park. Result: a lot of money in city coffers from successful urban renewal initiatives.

- The Gazelle Park has become a tourist attraction, apart from having become a global bird lovers’ destination. Result: income for the city, when tourists add a day to their schedule to include the park.

These points illustrate the economic significance of one urban nature park in Jerusalem. There are many additional projects, and many more potential ones. I would posit that in Jerusalem, as in almost any other city, nature-based solutions can and should play an integral role in the urban economy, alongside other significant urban sectors.

about the writer

Taícia H. N. Marques

Doctor of Sciences on Landscape and Environment- FAU-USP, Associate Professor and Concytec researcher in the Department of Planning and Construction- UNALM. Especially interested in researching the designing and installation processes of Green Infrastructure and Nature based Solution in cities. Partner at PERIFERIA, an organization which works with different stakeholders and the community to increase nature in Peruvian cities.

Taícia H. N. Marques

The design of business models to support and scale up NbS in Peru is challenging once it encompasses a range of actors and sectors that usually are not used to collaborating. To move towards Nature-based Economy there is a need to bring those different actors to the same page of comprehension regarding Nature-based Solutions.

How do we go from nature-based solutions to a nature-based economy?

This is maybe one of the trickiest questions we must answer, and I am sure there is not only one fine response. Climate change is already a motor of change, or at least, a motivator of transnational discussions and pacts of changing since quite some time now. Nevertheless, I have the impression the pandemics of COVID-19, recently reinforced by the last IPCC publication, made us, or at least some of us, more connected and aware of the urgency with which we must act. Somehow it shows up a possibility to “re-start” on a much more natural way. On the other hand, the financing of NbS actions to face Climate Change during the recovering from the pandemics is still low. That was/is the moment Nature-based Solutions started to pump up on diverse publications and began gaining more attention in South America, including Peru. This umbrella concept, proposed to put under a common term a bunch of already known techniques and ecosystem approaches, opens new possibilities to different experts and sectors, who normally work focused on one issue, to cooperate and recommend integral solutions for complex problems.

Peru is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world, what makes it one of the most vulnerable areas regarding climate change impacts. Besides that, it faces political and socioeconomical challenges that increases environmental disasters risks and its consequences. During the past decade the country has been closely involved on global and regional pacts for climate, assuming it has an important role to play. Environmental policies in the country are novelty once the Ministry of Environment was only created in 2008 focused on nature conservancy. Nature and economy had traditionally taken different paths, as well as social inclusion, but a possible shift of the business-as-usual model is being recently proposed here.

Currently, the country defined two ways towards the sustainability and resilience. The National Policy of Competitivity and Productivity, approved in 2018 by the Ministry of Economics and Finance, incorporates strategies of circular economy to achieve sustainability. It is being complemented by specific roadmaps designed by the Ministry of Environment (MINAM), to guide each one of the most representative economic sectors of the country (industry, agriculture, fishing, and aquaculture), on closing its looping. In parallel, also very fresh, policies and regulations focused on Climate Change mitigation and adaptation are being launched by MINAM. From that, 154 National Determined Contributions are planned, among them Ecosystem based Adaptation (EbA), Natural Infrastructure (IN) actions and different approaches to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions to target 2050 neutrality. Together the two groups of policies settle the bases for Nature-based Solutions in the country and open precedents for a Nature-based economy to be developed. Even though this terminology is very new here, the NbS is already cited on official documents referencing the planned NDC.

Due to the freshness of those policies, together with the institutional debility that affects the country and the commitment it demands to re-think the current economic model, its effectiveness is still unknown. However, it can be a great possibility to impulse Nature-based Solutions and Nature-based Economy together in Peru. What can be current observed is that local EbA and IN interventions have succeed on empowering communities to work with nature to benefit themselves by improving small economies in rural areas, while conserving, restoring, or creating new ecosystems. Yet, the design of business models to support and scale up NbS in Peru is challenging once it encompasses a range of actors and sectors that usually are not used to collaborating. Urban areas also represent a gap of action that should be taken. To move towards Nature-based Economy there is a need to bring those different actors to the same page of comprehension regarding Nature-based Solutions potential and application on different areas of the territory.

about the writer

Eduardo Guerrero

Eduardo Guerrero is a biologist with over 20 years of experience in projects and initiatives involving environmental and sustainable development issues in Colombia and other South American countries.

Eduardo Guerrero

Some key challenges (and opportunities) of the urban circular economy for a tropical megadiverse country are: (1) Urban metabolism analysis leads to better decisions; (2) Green entrepreneurship creates a culture of sustainability; (3) Local citizen can drive a circular economy.

Circular economy as a nature-based solution for green and sustainable cities in a megadiverse country

Circular economy is actually a nature-based solution, in which business and productive activities emulate an ecosystem’s efficiency regarding the use of water, raw materials, biomass and energy. So, the main contribution of this concept is the link of economy and nature encouraging an evolution of the conventional economic view about nature as if it were an external factor and an endless spring of resources. In fact, economic and ecological cycles are closely interlinked, so dichotomies that confront economy and environment are more than ever unwise.

Akin to related concepts such as bioeconomy, biotrade, climate economy, green growth, and green business, the circular economy model is generating a new paradigm pointing to a sustainable economy aligned with a global energy transition and biodiversity conservation urgency.

integrating urban biodiversity and ecosystem services. Photo: Eduardo Guerrero

Circular economy in a megadiverse country

In terms of economy-nature synergies, the ecosystemic context and economic emergent dynamics of a country with a high biodiversity such as Colombia offer important opportunities, and challenges related to circular economy implementation.

Cities and metropolitan areas in the Caribbean, Andean, Pacific, Amazon and Orinoquia regions have an enormous space for improvement and the generation of new ventures associated with regional nature advantages.

Circular economy links ecosystem cycles and services, so that the potential of the exceptional Colombian biodiversity is better utilized. And there, clearly, an urban-regional territorial approach is required in which cities are the leveraging nuclei of productive activities and nature conservation, at the same time.

Colombia is a regional leader in terms of public policies promoting circular economy. The National Strategy of Circular Economy was launched in 2019 involving a strong partnership among public and private stakeholders. Moreover, the new stage of the environment policy for cities includes urban circular economy as one of its strategic focuses.

Urban circular economy

Within the global current transition scenario towards a sustainable zero-carbon economy aligned to a halted biodiversity loss, cities are fundamental spaces. Likewise, sustainable cities require a strong development of circular economy schemes, since they are home to a good part of the productive activity and, in addition, the largest population of consumers.

In a city evolving towards sustainability, nature should be an integral part of the urban planning, so that infrastructure, buildings, and mobility corridors are articulated with ecological networks, which are the natural support base for economic production cycles.

Economy and ecology find an opportunity for synergy in urban areas, inspired by the common benefit and pointing to integrated goals of environmental sustainability, economic competitiveness, and social inclusion.

From the perspective of a tropical megadiverse country, some key challenges (and opportunities) of the urban circular economy to consolidate green and sustainable cities are:

Urban metabolism analysis to make better decisions both economic and environmental

To approach the planning of a city in the perspective of the circular economy, one must begin by understanding its metabolism, i.e., the balance between inputs and outputs of water, energy, materials, and biomass. Urban biodiversity and ecosystem services should be an integral part of the analysis.

And we must not forget the social and economic dynamics. Therefore, the analysis of urban metabolism must be systemic, integrating ecological, economic, and social flows.

Therefore, it would be advisable to carry out studies and analyses of urban metabolism for each of the country’s city-regions, identifying these particularities, comparative advantages, and opportunities for entrepreneurship.

Green entrepreneurship articulated with a culture of sustainability, circularity, innovation, and competitiveness

There are multiple opportunities for the development of enterprises based on the bioeconomy with circularity criteria that articulate existing capacities in urban centers with the comparative advantages of the biodiversity of each city-region.

Businesses based on technologies for water reuse, biotechnology, urban agriculture, nature tourism on an urban-regional scale, bio-commerce with an emphasis on local products (with a low carbon footprint), improved production and marketing of natural medicines and nutraceuticals. These and other green business can be integrated into circular economy models with a greater efficiency in the use of resources inspired on ecological cycles.

Local and citizen-driven circular economy

In addition to public policies and private sector commitment regarding circular economy, a key decisive challenge is to achieve a solid appropriation of circular habits by citizens.

At a local and neighborhood scale, strong education, training, and participation initiatives should be supported dealing not only with concepts but mainly with best practices. Rain harvesting, home composting, source separation, reuse of packaging and discarded objects, including their creative transformation into toys, ornaments, costumes, boxes, homemade tools, among others, must be disseminated and expanded.

Circular economy begins at home.

about the writer

Simon Gresset

Simon Gresset is a Circular Economy Officer at ICLEI Local Government for Sustainability. Involved on various projects at European level, he supports local governments in enabling and promoting more circular systems. He is also keen on reminding how the circular transition can help in meeting their environmental, social and economic goals. Simon has an academic background in political sciences and urban planning and previous experiences in innovation management as well as in environmental policy at local government level.

Simon Gresset

A project to expand canopy in Paris would undoubtedly improve the quality of life of locals, and it could in turn create new investment opportunities, spark new interests among communities for the environment and foster new initiatives, constituting some sort of virtuous circle.

The plan comprised a lot of different conventional actions, such as tree planting and ecosystem restoration, but also the development of support tools, such as a spatial analysis platform to identify areas where renaturation was the most important (based on a set of both environmental and social indicators) and a tool aiming at selecting the most adapted tree for each development based on context and on ecosystemic services it could provide. It also integrated measures aiming to raise awareness among local communities. This plan wasn’t obviously going to substantially boost the local economy or significantly transform the urban environment. Still, since its inception it has been supporting useful research and innovation projects while also directly creating several jobs related to the nature based-economy locally. Over the years, it will positively impact the urban environment, making the air more breathable and less warm in summer, and will strengthen the social fabric, creating bonds between inhabitants through community initiatives such as urban gardening.

Overall this will undoubtedly improve the quality of life of locals, and it could in turn create new investment opportunities, spark new interests among communities for the environment and foster new initiatives, constituting some sort of virtuous circle. This is a small example based on personal experience but I assume that the multiplication and upscaling of such actions at local government level can constitute the basis of a growing nature-based economy with a strong potential for both people and for the environment.

about the writer

John Bell

Dr John Bell is the ”Healthy Planet” Director in DG Research & Innovation. He is responsible for leading the Research and Innovation transitions on Climate Change within planetary boundaries, Bioeconomy, Food Systems, Environment and Biodiversity, Oceans and Arctic, Circular Economy, Water and Bio-based innovations.

about the writer

Tiago Freitas

Tiago Freitas lives in Brussels and is a policy officer at DG Research and Innovation of the European Commission, focusing on biodiversity and Nature-based Solutions. In the past, he has worked at the European Parliament (2004-2010), first as policy advisor and then as research analyst in structural and cohesion policies.

John Bell and Tiago Fritas

The potential is huge. However, unlocking full NBS potential will need a massive increase in investment, both public and private and will hinge on a paradigm shift in how our economies are organised and how they value nature and its services. A transformation is needed in our current business model, bringing local actors to the driving seat for changes.

Europe’s Green Deal Missions is to make peace with nature. Research and Innovation needs a greater level of ambition to set direction for this transition.

Our livelihoods, well-being and our chance to meet the global warming challenge all depend on Nature. Nature provides all sorts of essential services to humanity: clean air and water, food and pollination, it sustains tourism and leisure activities, it contributes to mental and physical health and delivers many other functions.

Nature, in many instances, is also the most effective insurance policy – protecting us from floods, landslides, fires or extreme heat. The tragic natural disasters that have hit Europe and the world this summer have all been a stark reminder of how much we need this protection. Natural capital stocks per capita have declined by nearly 40% between 1992 and 2014 and one million plant and animal species now face extinction. All this while roughly half of the world’s GDP is moderately or highly dependent on Nature.

This is a serious threat to our future welfare and calls for the development of an Economy that is more respectful of Nature.

At the centre of this paradigm shift are Nature-based Solutions (NBS). They are increasingly recognised internationally as a fundamental part of action for climate and biodiversity. A UNEP report issued last May states that investments in NBS need to triple by 2030[1] if the world is to meet its climate change, biodiversity, and land restoration targets.

A growing number of businesses is making the case for NBS already, but it is time to move from niche to a broader movement. Hence, while NBS are already being delivered, are visible and credible, we need a greater uptake, including through the supportive policy framework offered by the European Green Deal.

A recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic is another chance to bring back nature to the core of our societies. National Recovery and Resilience Plans, which aim to build a more sustainable and resilient economy across Europe are a once in a life-time opportunity for a nature-based recovery.

The potential for local job creation is tremendous, comprising both highly technical green jobs but also other jobs that are low-skilled, offering a chance to reach those who have been hit hardest by the pandemic.

The potential is huge. However, unlocking full NBS potential will need a massive increase in investment, both public and private, and will hinge on a paradigm shift in how our economies are organised and how they value nature and its services. A transformation is needed in our current business model, bringing local actors to the driving seat for changes.

We need to move towards:

- An Economy that puts Nature at its heart and acknowledges that biodiversity is absolutely essential to secure long-term sustainable economic growth;

- An Economy that is aligned with Nature and Climate goals, including through incentive structures, fiscal and budgetary policies;

- An Economy with more holistic objectives and measures of progress that look beyond economic growth/GDP

Such an Economy would create opportunities for viable, large-scale NBS across various sectors, while creating a win-win for nature, climate, and the people.

We have mobilised research and innovation to support policy here: 28 projects are underway worth EUR 240 million on demonstrating how to deploy NBS. Additionally, large-scale ecosystem restoration projects on land and at sea from our Horizon 2020 Green Deal call (mobilising EUR 86 million) will start this autumn.

NBS also feature prominently in Horizon Europe’s Work programmes for 2021-2022, in the Biodiversity Partnership as well as in Horizon Europe’s Missions, notably the one on Adaptation to climate change and Oceans.

In a nutshell, we are not short of ideas. Science is clear on what needs to be done, but it is time to deliver innovation, demonstration of NBS across policy, business, and civil society.

Opportunities are plentiful and it is entirely in our hands to move to a greener, safer, and more equitable economy that leaves no one behind, now that the world grapples with unprecedented climate and biodiversity emergencies.

[1] And to quadruple by 2050, Source: State of Finance for Nature | UNEP – UN Environment Programme

about the writer

Antonia Lorenzo