We need to reimagine the institutional landscape of urban disputed commons governance to accommodate diverse goals and management practices that simultaneously produce good and bad commons. On one hand, practices of good commoning produce bad commons. On the other hand, if disputes were to be resolved, the land would likely be privatized, halting the practices of good commoning.

Can practices that produce “good” commons also create “bad” commons? In some instances, practices of commoning spaces that are neither public, private, nor common can also degrade these spaces.

Mornings in my neighborhood of Wanowrie in Pune city, in the western state of Maharashtra, India are a charming sight. An undeveloped parcel of land also known as Kakade ground, approximately 48 acres in size, is the center of Wanowrie’s universe. An enthusiastic and dedicated youth group begins the day with volleyball matches. Running and cycling groups gather at the local tea seller’s semi-permanent structure on the land for their post-exercise banter. Street dogs playfully loiter around them, yapping for a stray biscuit. Residents may be shopping for fruits and vegetables at nearby popup stalls. The elderly may assemble at a corner of the land for their morning constitution and some healthy neighborhood gossip.

On some days, youth wings of local political groups organize cricket and soccer matches, bringing the passing traffic to an eager halt to watch the game. Strategically placed benches provide rest, and traditional water pitchers quench the thirst of the weary. Weekly and semi-permanent farmer markets save residents a trip to the inner city for produce. These decentralized produce markets provided an essential service during the COVID-19 induced lockdowns. Street vendors and fast-food selling hawkers take over the land in the evening. Approximately, five times a year, the land hosts artists and small businesses all over India, automobile exhibitions, book fairs, circuses, and fun-fairs. The land also provides space for local residents to learn and hone their car and bike driving skills. Occasionally, the land becomes home to migrant laborers and the nomadic Dhangar tribe with their sheep, camel, goats, and horses. Some trees on the land have threads tied around their barks, indicating that local residents may be worshipping the tree. Thus, a “good” commons results from these various uses that miraculously do not conflict with each other, but instead create a vibrant neighborhood.

With multiple people using the land as an open-access “good” commons, “bad” commons are close behind. The waste from the farmer’s market and street vendors accumulates on the land. Plastic bags, in which residents bring food for the nomadic and migrant communities, litter the land. A cow-shelter that pious residents constructed to house cows on the land generates a steady stream of waste. Housekeeping staff of the surrounding gated communities dump trash on the land. Burning the trash engulfs the neighborhood with noxious fumes. Passing men use the land as a urinal. Pigs, dogs, donkeys, camels, horses, crows, pigeons, and flies abound. Mosquitoes, in particular, pose a real threat of malaria and dengue. In the absence of a natural predator, pigeons are a growing menace with the city registering wheezing cases related to pigeon droppings. Thus, the very process of making the commons is also degrading the commons. In the absence of maintenance, commoning is endangering the well-being of residents and people using and accessing the land.

Such parcels of undeveloped land are common not just in Pune, but across India because these lands are usually entangled in a legal controversy. The Center for Policy Research, New Delhi estimates that 7.7 million people in India are affected by disputes over 2.5 million hectares of land, affecting investments worth $200 billion. 66% of all civil cases in India are related to land/property disputes and the average timespan of a land acquisition dispute, from the creation of the dispute to its resolution by the Supreme Court, is 20 years.

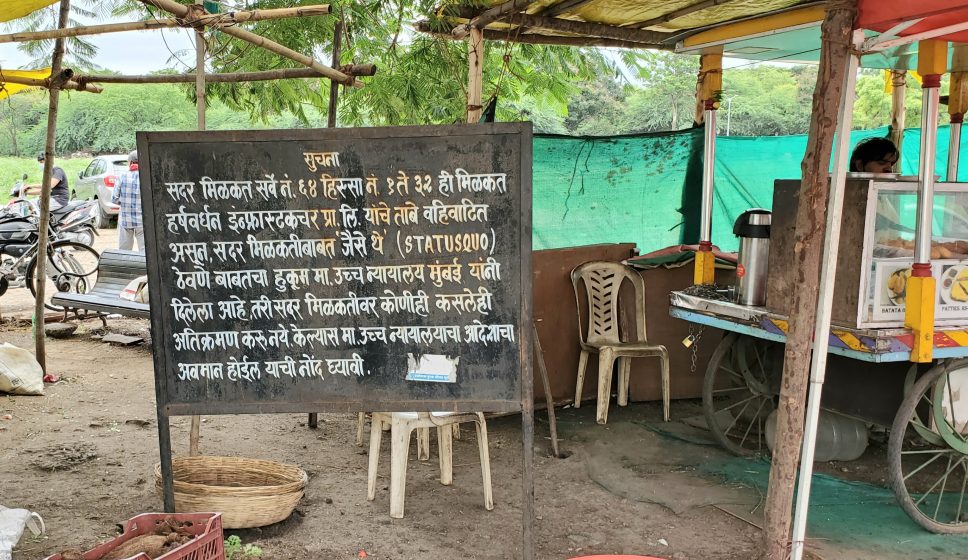

Like other undeveloped legally disputed parcels of land in India, the land opposite my home is similar. This dispute can be traced back to two land developers who earmarked the land in 1957 for a shopping mall, multiplex, restaurant, corporate park, and a hotel with exclusive apartment units. The dispute is complicated by the fact that the land was granted to the people to be held in trust and can only be sold with the District Collector’s permission. The departments of revenue and forest are also involved. These departments have passed a stay order against the sale of the land to the developers. In 2009, the Pune Cantonment court directed the police to inquire into the land dispute, which is still in progress.

When resources are legally disputed, who should have the responsibility for maintaining the “good” commons generated through commoning? Is it the police department that is conducting the inquiry? Is it the court or the departments of revenue and forest? Is it the Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) that collects rent from the street vendors and hawkers but cites the dispute as a reason to not clean up the land? Is it the land developers who also collect rent from the vendors on the land? Is it the wealthy and middle-class residents of this plush neighborhood who are the main actors in the making of the commons?

Sheila Foster argues that when governments are unable to provide essential services or are not able to oversee and manage resources, a situation called “regulatory slippage” arises. In such situations, the resource is vulnerable to degradation because of competing users and uses. When regulatory slippage occurs, a group of actors with high collective efficacy i.e., strong social ties and networks may fill the vacuum in governance. At Kakade ground, residents voice their concern at the trash and occasionally conduct cleanliness drives on the land, but these sporadic efforts do little to arrest land degradation. Thus, for Kakade ground, a 20-year-old practice of commoning to create a “good” commons may have built collective efficacy among residents, but the exercise of that collective efficacy for maintaining the commons is yet to be seen. Perhaps the land dispute[1] may be preventing them undertaking long-term action.

Practices that simultaneously produce good and bad commons on disputed spaces raise several questions for future inquiry:

- What happens when the commoning of legally disputed spaces occurs without explicit or implicit intent to common that space?

- What are the unforeseen, unpredictable, and undesirable consequences that emerge from the use and access to such disputed spaces?

- What is the role of the state in such situations?

- Would residents have maintained the commons if the space were not disputed?

- On one hand, practices of good commoning produce bad commons. On the other hand, if the dispute were to be resolved, the land would likely be privatized, halting the practices of good commoning. Thus, with or without the resolution of the dispute, residents stand to lose the most. Therefore, what could be the form and nature of collective management for such legally disputed resources?

Despite critical advancements in the scholarship on common-pool resources, studies on rural commons dominate the field. While research on urban commoning is growing, scholars are yet to delve into the commoning of legally disputed resources. Where resources don’t neatly fall into categories of private, public, and commons, approaches to manage such kinds of resources are also missing. The undeveloped land in my neighborhood accommodates multiple uses, reflecting the diverse social goals of different groups of people. There is therefore a need to re-conceptualize and reimagine the institutional landscape of urban commons governance to recognize and accommodate diverse goals and practices that simultaneously produce good and bad commons.

Praneeta Mudaliar

Ithaca

Note: [1] Residents developed a community garden at an undisputed dumpsite, a few meters away from Kakade ground.

Leave a Reply