“Lakshmamma thought sadly of her grandchildren, growing up in the city, in a crowded slum with no thope to run around in or trees to climb.”

This excerpt, from our bilingual book “Where have all our gunda thopes gone?”, is a story of loss and hope—loss of nature as a city expands and hope that our readers will be encouraged to protect nature in their neighbourhoods.

Though the characters are fictional, the setting and experiences are based on conversations we have had with residents living in a village in peri-urban Bengaluru—and one of the sites of our research on commons.

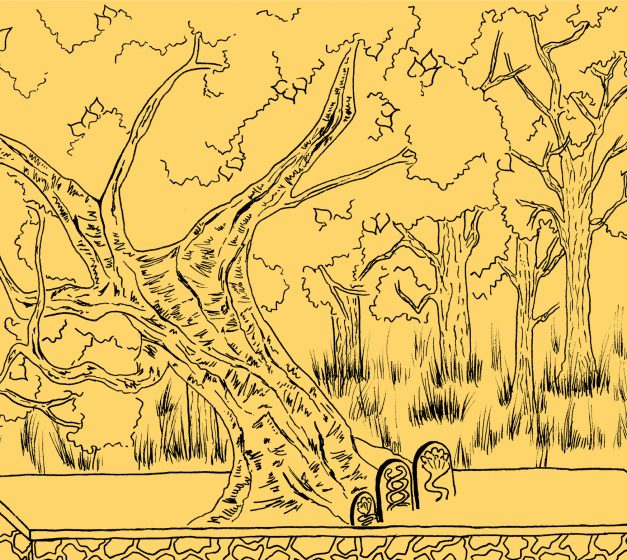

Gunda thopes (or wooded groves) are an important common once found across the state of Karnataka in Southern India. Historically, thopes have been an integral part of the rural landscape, planted with fruit and timber yielding trees, and cared for by the local community. But, in recent times, there have been transformations to these thopes especially in the peri-urban interface of cities such as Bengaluru, the capital of Karnataka. Our story is about one such thope that transformed from a grove of towering mango (Mangifera indica) and jamun (Szyzygium cumini) into a landscaped park with lawns and ornamental plants.

We have brought out this booklet at a time when rapid urbanisation with its challenges of sustainability and equity is being witnessed in the Global South.

Our story follows Lakshmamma, who lives in Bengaluru, and who has returned on a visit to her natal village after many years. Lakshmamma is amazed at how much had changed—the village situated now in the peri urban interface of Bengaluru, looked more like a city to her. On her last evening in the village, she retraces her steps past commons, like the pond and lake, making her way to a gunda thope she visited often as a child.

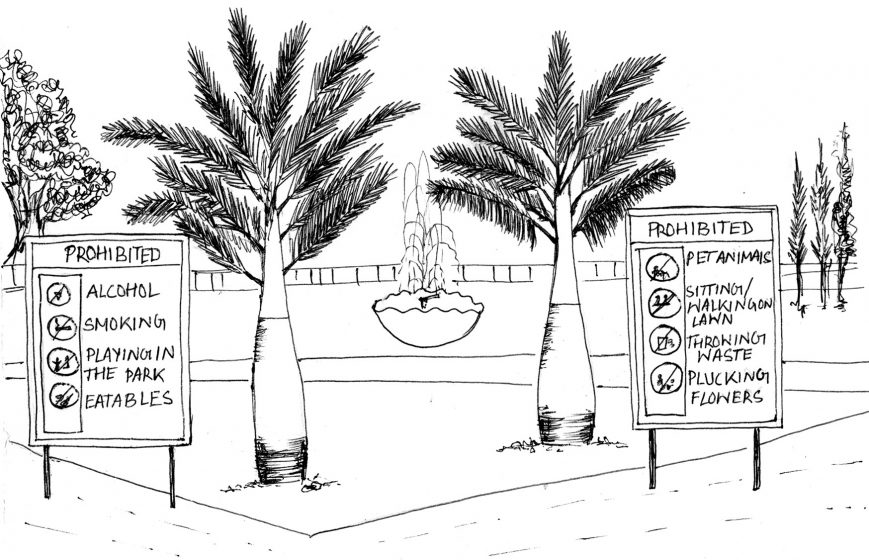

Lakshmamma is shocked at what she sees. Instead of a thick grove with trees, what she sees is a landscaped park—similar to the parks in the city she lived in now. A large fence, a signboard with “do’s and don’ts”, exercise machines, a playground, and perfectly trimmed trees greet Lakshmamma.

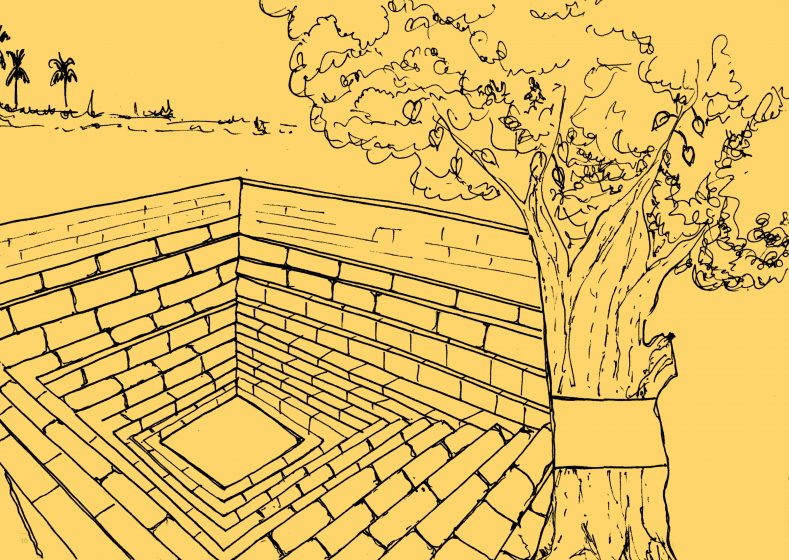

Walking through the park, Lakshmamma is filled with bitter-sweet memories. She then spots a majestic peepul (Ficus religiosa) tree—she had fondly named Maranna (tree brother) as a child. The rest of the booklet is a conversation between Lakshmamma and Maranna about the changes to the thope.

The conversation weaves through Lakshmamma’s childhood, the many happy hours she had spent in the thope—playing with friends, eating mangoes, grazing her goats. But it soon turns sad as Maranna tells her about how the thopes and their uses had changed over time—and the slow erasure of thopes from even the community’s memory. Lakshmamma mourns the loss of the commons, thinking sadly of her grandchildren living in the city who will never experience the abundance of gunda thopes that Lakshmamma did as a child.

The story of this story

Though the characters are fictional, the setting and experiences are based on conversations we have had with residents living in a village in peri-urban Bengaluru—and one of the sites of our research on commons. The thope has indeed been transformed as described in the story. But is not an exception. Other urban and peri-urban commons such as lakes, ponds, cemeteries, and grazing lands have witnessed a similar fate. Some commons have been converted to schools, roads, bus stops, community centers, housing, and so on. As a result, the ecological benefits that these green and blue spaces provided have been lost forever. Others, like the thope in the book, have been converted to parks and spaces of leisure. Stripped of their native vegetation, we now have perfectly manicured lawns, fenced walls, and several rules and regulations that prioritise recreational use of the urban elite and middle class. Meanwhile, the conversion, enclosure, and gentrification of what were once commons have all marginalised traditional users and the local community who had livelihood, social, and cultural connections extending across generations.

Our research on the transformation of and contestations around thopes and similar urban and peri-urban commons has been published in peer-reviewed journals (Mundoli et al 2017, 2018) and used as a teaching case study in the MA Development programme at Azim Premji University. Students have also visited our field sites to undertake land use and biodiversity mapping.

But one of the questions we asked ourselves is:

“How can we communicate our research to a wider public, and partner with them in protecting the city’s environment?”

The story of Lakshmmamma and Maranna is our attempt to do that and, in order to make it more accessible, the booklet has also been illustrated.

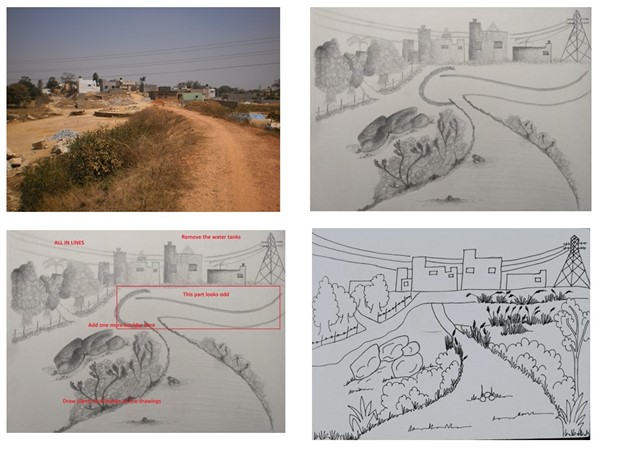

We decided early on that illustrations would be an integral part of the story. The first step for us was to identify what illustrations could fit the storyline. Once this was done, the illustrators read some of the field notes and publications and looked at photographs taken during field visits over the years. Next, rough sketches were drawn by the illustrators and, if the sketches resonated with the storyline, the sketches were completed by adding details.

Illustrations as a new way of conversing about urban commons

We did not want the illustrations to direct too much attention away from the story. Rather, we wished to complement the story. The simple hand-drawn black and white line-art enabled us to achieve this effect. It was an added advantage that, while there were three of us illustrating, our styles were similar, enabling us to achieve a consistency in the illustrations. Apart from adding power to storytelling, the illustrations also act as a tool that allows readers to imagine the story of the thopes. Through the illustrations of Lakshmammas lined face, the spreading branches of Maranna, the lake surrounded by agricultural fields, and several others the readers are able to visualise the landscape of the village as it once was. Similarly, through the illustrations of the park and the school into which the thopes were converted, readers are able to relate to what the thopes have become. We feel that this allows the readers to sympathise with Lakshmamma and Maranna’s story more deeply. Illustrating a book was a new experience for the illustrators—and it was an exciting venture to convert an academic publication into a more widely accessible format. This experience also provided us an opportunity to converse about urban commons in a new way.

A wider outreach of the story

India is a country of many languages, and also of many similar thopes, albeit by different names, spread across the country. For a wider reach, the booklets were conceptualized as bilingual and were translated into two languages—Kannada, spoken in Karnataka, and Hindi a language familiar across other states. Printed copies of the English-Kannada version have already been distributed through the Department of Panchayat Raj and Rural Development across 6400 rural libraries in the state of Karnataka. In addition, we prepared illustrated worksheets for teachers and educators on the topics of commons, benefits of trees, and maintenance of commons under the rights-based legislation, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. The worksheets elaborated include activities that involve students identifying commons and engaging with nature around them. The objective is to create awareness among children and encourage collective action to protect the disappearing commons. The Department is also considering an awareness campaign that includes identifying thopes and working with the local community in planting and maintenance for which we are collaborating as well.

Conclusion

We have brought out this booklet at a time when rapid urbanisation with its challenges of sustainability and equity is being witnessed in the Global South. We especially recognise the important role that commons play in countries like India, and the contestations around commons as cities sprawl into the peri-urban adversely impacting local communities and ecosystems. But we also realise that communicating these challenges and raising awareness is the first step towards forming partnerships in protecting commons. And our illustrated book “Where have all our gunda thopes gone”, seeks to do just that.

Sahana Subramanian, Neeharika Verma, Sukanya Basu, Seema Mundoli, Harini Nagendra

Lund, Amherst, Göttingen, Bangalore, Bangalore

about the writer

Neeharika Verma

Neeharika Verma received her undergraduate degree in biology from Azim Premji University, and is currently pursuing her master’s in marine science from the University of Massachusetts, USA.

about the writer

Sukanya Basu

Sukanya Basu was a Research Assistant at the Azim Premji University and is pursuing her PhD in Sustainable Food Systems from University of Göttingen, Germany.

about the writer

Seema Mundoli

Seema Mundoli is an Assistant Professor at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru. Her recent co-authored books (with Harini Nagendra) include, “Cities and Canopies: Trees in Indian Cities” (Penguin India, 2019), “Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India’s Cities” (Penguin India, 2023) and the illustrated children’s book “So Many Leaves” (Pratham Books, 2020).

about the writer

Harini Nagendra

Harini Nagendra is a Professor of Sustainability at Azim Premji University, Bangalore, India. She uses social and ecological approaches to examine the factors shaping the sustainability of forests and cities in the south Asian context. Her books include “Cities and Canopies: Trees of Indian Cities” and “Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India’s Cities” (Penguin India, 2023) (with Seema Mundoli), and “The Bangalore Detectives Club” historical mystery series set in 1920s colonial India.

Leave a Reply