Video data gathering captured the spatial and temporal distribution pattern — the flux/flow — of the ecology of small lanes in Bangkok. It suggests that we should stop seeing cities in terms of centers and peripheries, a residual concept of colonial metropolitanism, but as patchy distributive ecological systems, where every point in the system has value.

Sois, or lanes, are the capillaries of Bangkok, Thailand. Like rectangular blocks in New York City, or piazzas in Rome, they constitute the architecture or the DNA of the city. For anthropologist Erik Cohen, a Bangkok soi constitutes an overlooked “semi-autonomous ecological sub-system” which comprise the “interstitial hinterland” between the dominating lines of urban development and expansion. As the megacity of Bangkok continues to grow along ribbons of wide roads, sois are the informal, unplanned, in-between micro spaces that still make the city varied, interesting and livable. The Bangkok soi remains a particularly revealing unit of analysis to understand the nature of fast-growing Southeast Asian cities like Bangkok.

Cohen conducted his fieldwork during the summers of 1981 through 1984; co-author McGrath lived in Bangkok between December and May from 1998 to 2007; and Diwadkar just arrived in December 2020 in time for the city’s first COVID lockdown. McGrath’s field research chronicled both the centripetal growth of the center of the city with the construction of the first mass transit lines and the extensive centrifugal expansion of the city with the construction of an outer ring road at the beginning of the millennium. In the decade between Cohen’s and McGrath’s longitudinal fieldwork, Thailand was the world’s fastest-growing economy before the Asian financial crisis of 1997. Between 2006 and today, Bangkok has been the scene of continuing political conflict, including two military coups. At the time of Diwadkar’s arrival, COVID shut the entry doors to one of the world’s most visited tourist hotspots and dampened ongoing street protests.

The ecology of Bangkok’s sois have continued to adapt and change in a way Cohen could only begin to imagine in the early 1980s. Sois remain bounded physical environments condensing both social contact and ecological interactions. As Cohen noted, they mark the transitions of rural patterns of canals, pathways, and fields that become unevenly urbanized during various periods of development. As such, they constitute a dynamic and heterogenous patch matrix of social, built, and vegetated structures that often temporarily revert to flooded waterways during rainy season.

Affinities between the architecture and ecology of the city can advance urban ecology beyond social metaphors. The concept of the metacity, postulated in both urban design and urban ecology, positions the science and design of cities up-close embedded within complex lifeworlds, but also reflects on patterns and processes with objective methods remotely. A metacity approach has the potential to address both the cultural and ecological dimensions of environmental justice and the climate crisis by making accessible the descriptive ecological and projective architectural tools through everyday handheld digital videography to collect data information on patterns, micro-climates, movements of the city, in both biophysical and social science senses.

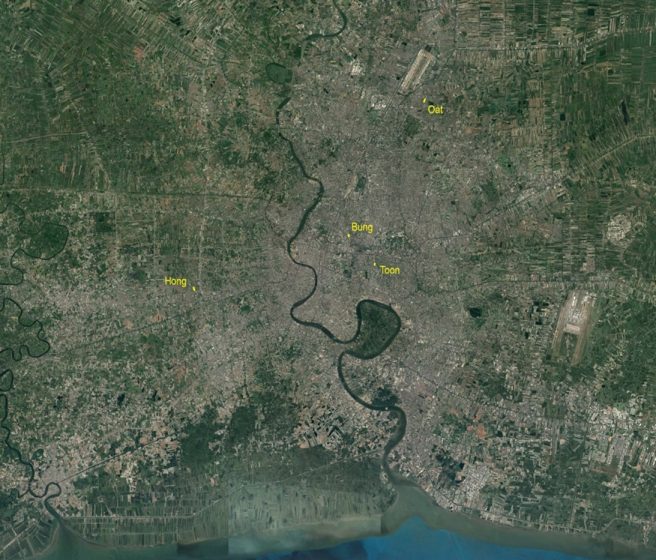

The Bangkok Metropolitan Area: Inside-out

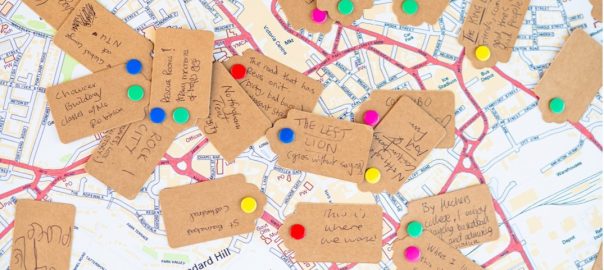

The two authors returned to the topic of the ecology of Bangkok’s sois during the city’s first COVID lockdown in January 2021, as part of a ten-day remote design experiment workshop (DEX), for Chulalongkorn University Faculty of Architecture. We had the unique experience of understanding Bangkok through the simultaneous social-ecological observations of ten students participating in the workshop, locked down in the immediate areas around their dormitories or family homes across the entire Bangkok metropolitan area. Their video data, gathered over a few days, sheds light on the validity of Cohen’s initial fieldwork but also can be evaluated in relation to the centripetal and centrifugal forces of development that transformed both the city’s center and periphery, as documented by McGrath.

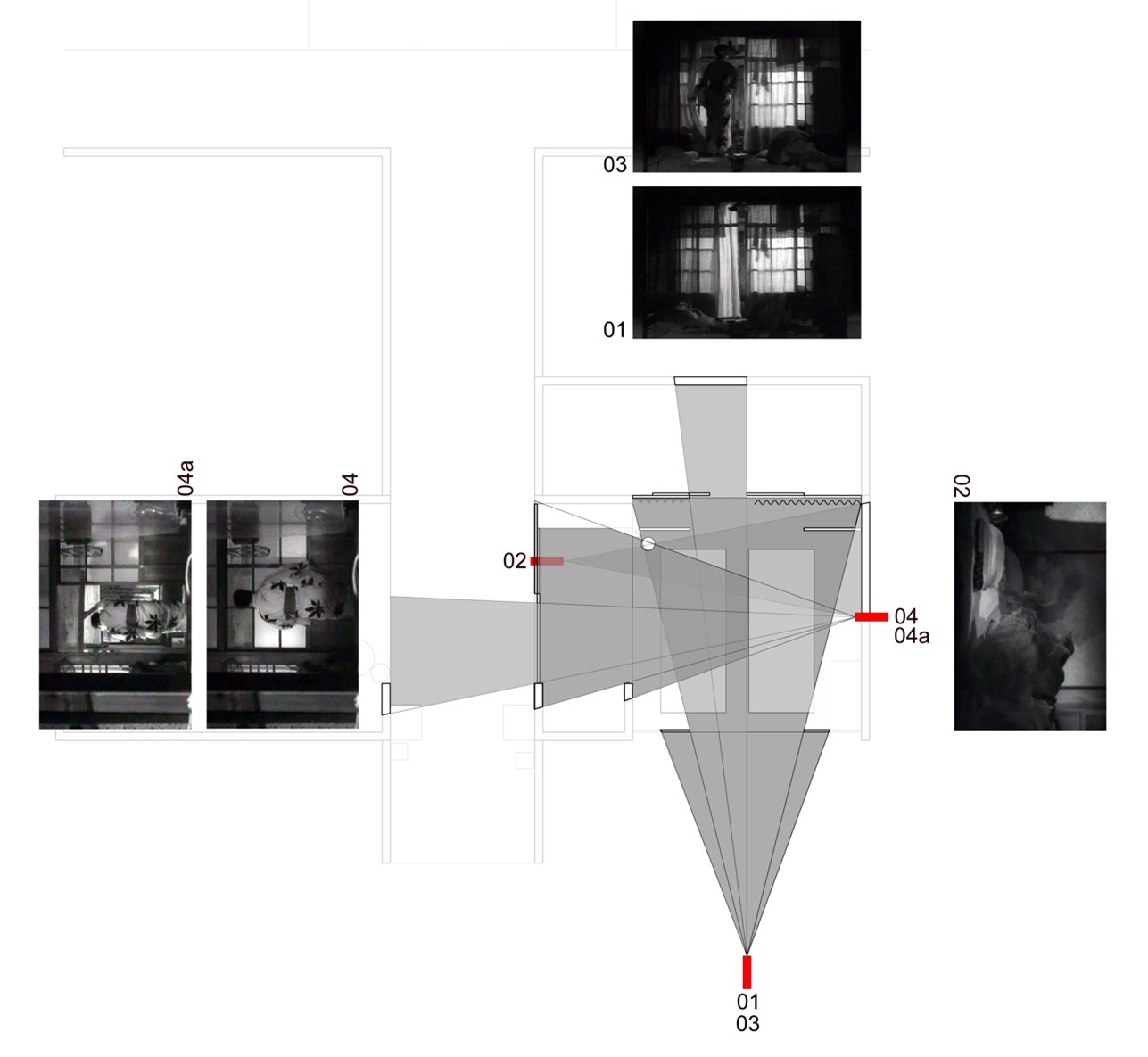

We organized the Design Experiment Workshop into two video exercises derived from The Cary Institute for Ecosystem Studies definition of ecology. The first videoed a 5-minute walk down a soi near their place of residence in order to study the processes influencing the spatial distribution, abundance, and interactions among and between organisms. The second exercise required visiting one ecological “hot spot” on the soi, framing the transformation and flux of energy, matter, and information from multiple camera positions and different times of the day. The workshop employed data gathering through the architectural application of film framing and editing techniques first described in the textbook Cinemetrics. Videography of everyday life is ubiquitous in an age of YouTube and Tik-Tok, but with a systematic framing method, pictures and sounds can create, in the words of philosopher Gilles Deleuze “sets of information”. We offer four examples of this fieldwork, from two students locked down in Bangkok’s periphery, and from two students in the central city. We use students’ nicknames to preserve their privacy.

1. Two 5-minute walks in Bangkok’s Periphery

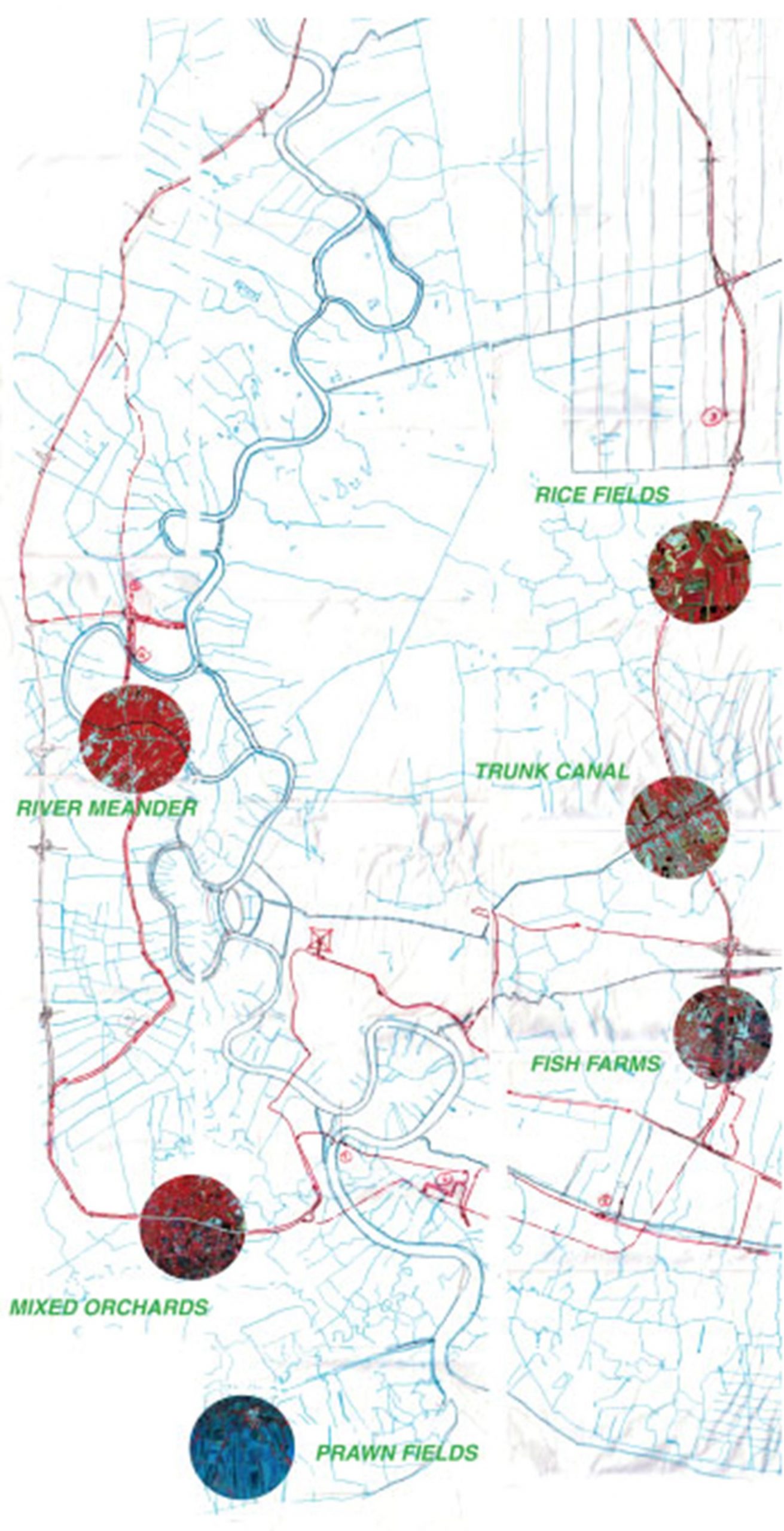

As documented by McGrath and Thaitakoo’s survey of the construction of Bangkok’s outer ring road, the centrifugal expansion of the metropolitan region has been conducted primarily through highway construction across agricultural land. The ribbon pattern that Cohen described in the urbanization of central Bangkok in the 1980s continues on the periphery today, as large areas between highways remain unplanned. Both housing estates and industrial zones are constructed as gated enclaves on patches of converted farmland between the commercial ribbons. The path of the ring road crossed huge tracks of wet rice fields to the north and east, major trunk canals that fill and drain the fields, fish farms and prawn fields near the coast to the south, and old fruit orchards to the west. The ring road crosses the mighty Chao Phraya River twice but also bridges several of the canals that follow the old course of the river.

Hong’s walk down Soi Phetkasam 88

In the western periphery, Hong documented the “interesting ecological heterogeneity” along the “interstitial hinterland” of Soi Phetkasam 88, a very dynamic soi crossing a former fruit orchard area and an irrigation trunk canal. The soi connects to an exit from the recently completed 12-lane Western Outer Ring Road, making it a shortcut by-path for many vehicles, including delivery cars, trucks, taxis, and buses.

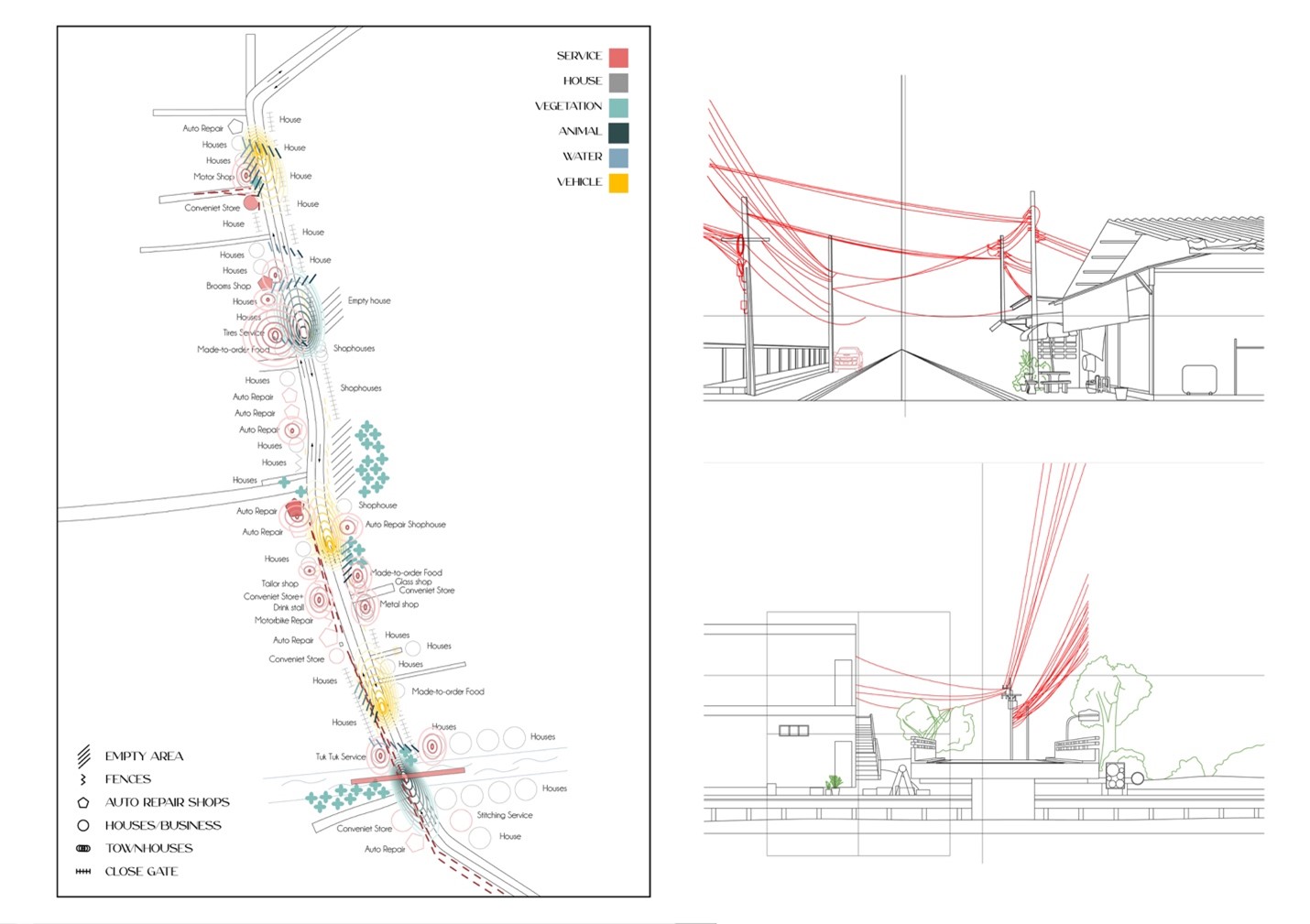

Hong’s 5-minute video walkthrough along Soi Phetkasam 88 records the ecology of a soi filled with middle to low-income housing, interspersed with multiple shops. The shops occupy quickly built, one-story sheds, and sell both village craft production, such as straw brooms, but also car mechanics, and, as everywhere in Bangkok, street food. At the end of the walk, a small bridge crossed over the Bangchak Canal, which continues to feed remnant fruit orchards as support older villages and new informal settlements.

Video of Hong’s 5-minute walk along Soi Phetkasam 88

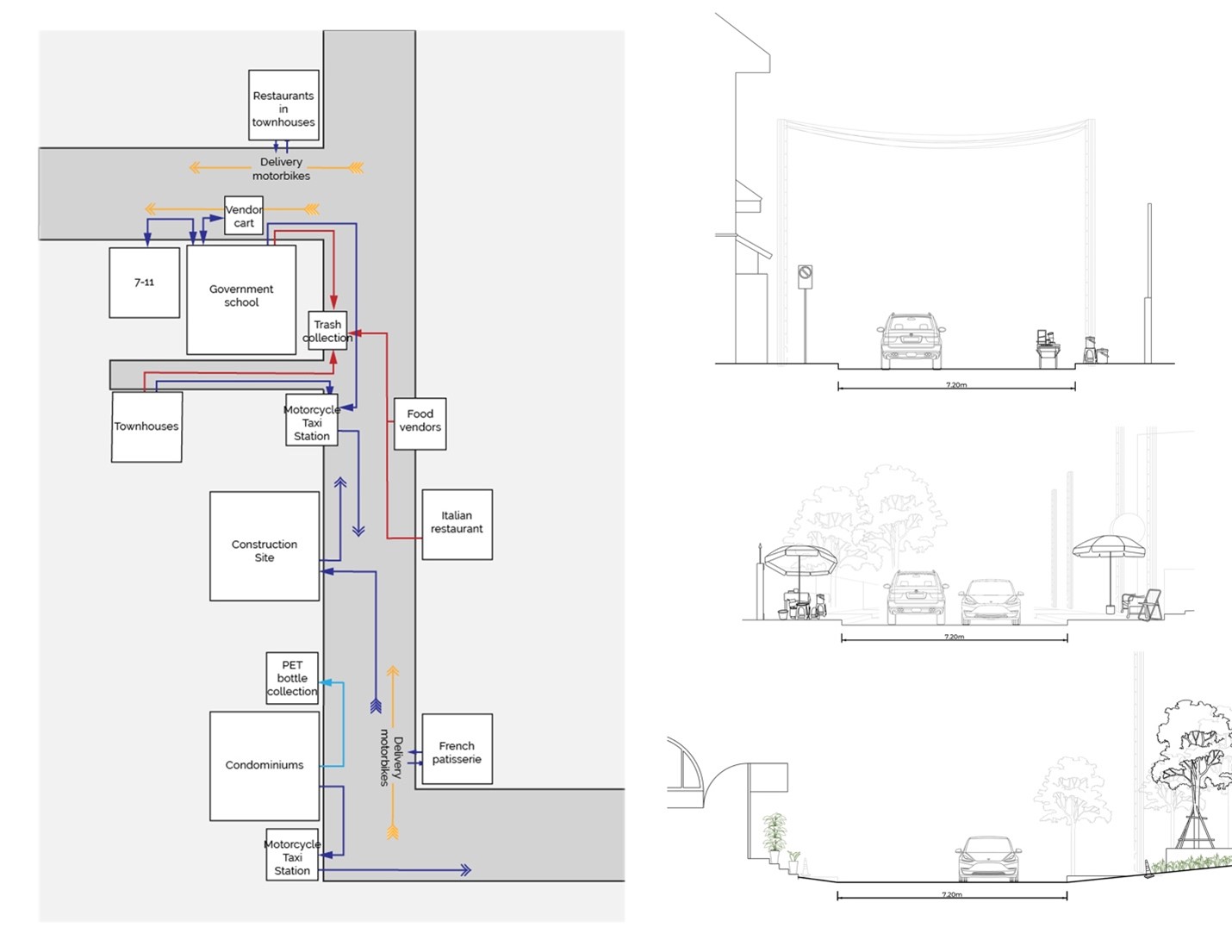

Mining the information on their video, students were asked to make a “soi shed” diagram. If a watershed map documents the catchment area of a river system, a soi shed maps the distribution, abundance, and interactions of sound, energy, material, organisms, and information encountered along a five-minute walk. Additionally, students were asked to construct four architectural cross-sections at key “hot-spots” of ecological interactions captured in their 5-minute video. The video itself is seen as a “moving section” through the soi, capturing 30 frames per second. Each drawn section shown is one of 9,000 possible cross-sections captured in the video. Each video frame can be seen as a slice of ecological information rather than a visual picture, and much like in an MRI scanning a living body, video frames can be analyzed as frozen moments of space/time.

Along Soi Phetkasam 88, there are temperate and tropical plants of various sizes and species competing with each other to grow as well as the colorful competition of various signs, flags, and awnings. There are all kinds of different residences, from one-floor and two-floor houses, shophouses, and small apartment blocks. There are no sidewalks, and all kinds of objects line the soi: cars, signs, waste containers, tables, sandbags, traffic cones, and merchandise for sale. Convenience stores line the soi, providing a small income and activity for older citizens who stay at home. Interestingly, as you walk along the path, there are also many car repair garages located next to the convenience stores. Here, the soi is a little livelier, with human interactions around the stores and garages, in combination with the chirping sounds of the birds.

Oat’s walk down Soi Sinsapnakorn

The northern periphery of the city has experienced development longer than the western frontier, especially following the expansion of Don Mueng, Bangkok’s first international airport, after World War II. This area was first developed for export rice field production, but became the location of inexpensive, densely packed single-family houses in gated communities when rice farmers sold land to developers from the 1960s. Soi Sinsapnakorn is the main lane of such an older suburban community.

Oat’s walk starts at the back south end of the soi and crosses six blocks of tightly packed single-family, walled, and gated homes along the soi to the west, and attached row houses further east. Potted plants, well-maintained gardens, and mature trees attract songbirds throughout. On the left, just before the soi crosses the Lam Phakchi Canal, there is a play and sports ground, occupied in the afternoon and early evening by a market.

https://youtu.be/FqjfzaL1A_k

Video of 5-Oat’s minute walk along Soi Sinsapnakorn

The Lam Phakchi Canal is a major trunk canal, a remnant of the irrigation system for export wet rice production. Along the soi, north of the canal, are four townhouse blocks with front extensions used for hanging laundry, car parking, or gardens. Some have been adapted to shophouses occupying the sidewalk with goods for sale. At the intersection with the 6-lane Thep Rak Road, there is an empty booth no longer occupied by a security guard. The soi is no longer gated since a new road was built as a cut-through to the south.

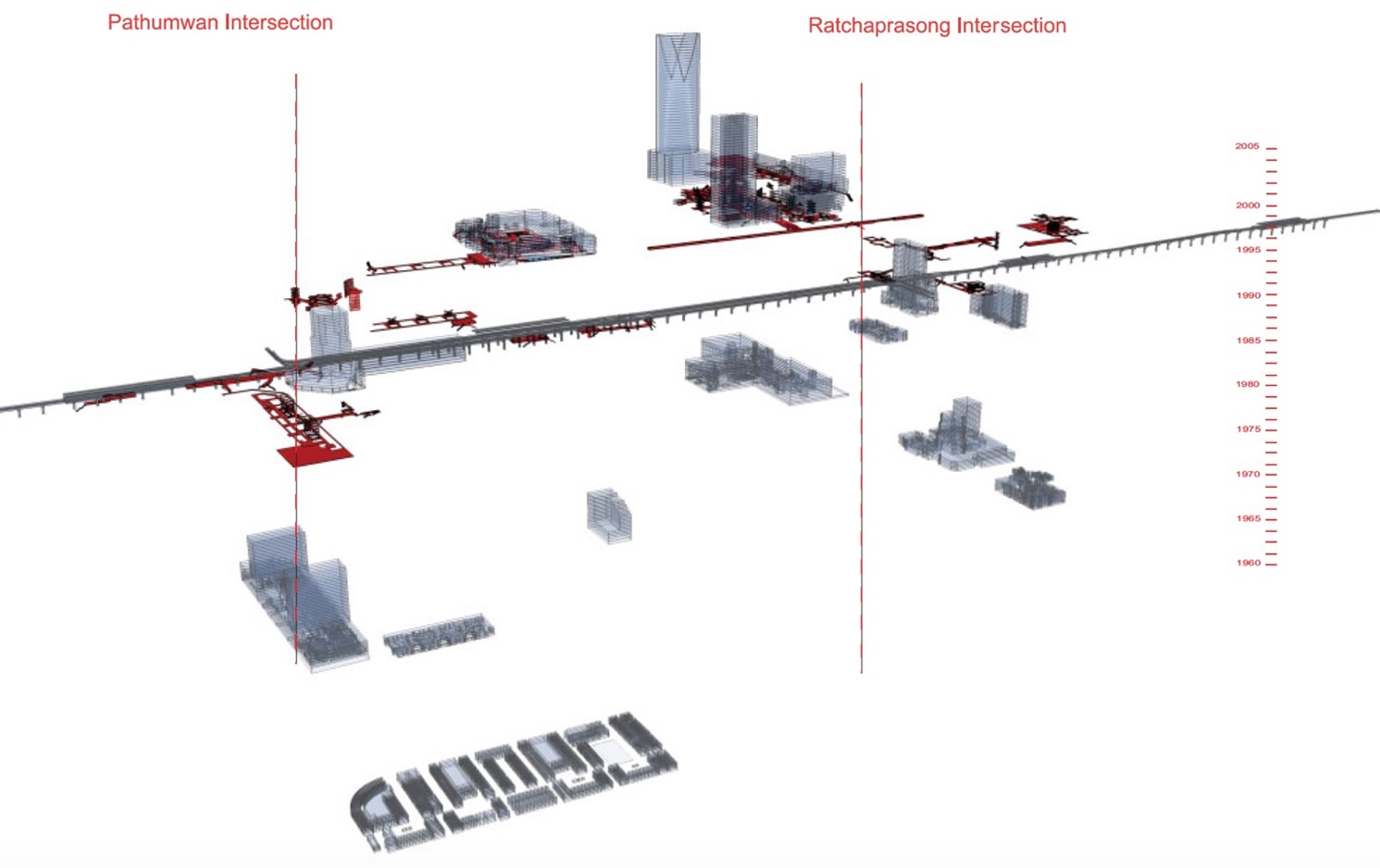

2. Two 5-minute walks in Central Bangkok

Central Bangkok has experienced an explosion of high-rise condominium, hotel, office, and shopping mall construction following the introduction of mass transit at the beginning of the millennium. The first two lines of the BTS Skytrain system, the Silom and Sukhumvit lines, meet at Siam Central Station, adjacent to Chulalongkorn University property. In addition to the research on Bangkok’s developing agricultural periphery along the outer ring road, from 2000 to 2005, McGrath also documented the transformation of this central node in Bangkok following the opening of the Skytrain. Data on the construction of shopping centers in the area since 1960 was compiled on a 3D digital model that also included a timeline that demonstrates the impact mass transit infrastructure had on the urban adaptation of the public realm of Central Bangkok.

Bung’s walk down Soi Ratchawithi 6

Soi Ratchawithi 6 is one of many sub-sois off Ratchawithi Road, a major east-west road that leads to Victory Monument. The BTS Skytrain Silom line skirts around the monument’s roundabout. Ratchawithi Road parallels the San Sem canal, a major waterway connecting to the royal garden district of Dusit and the Chao Phraya “River of Kings” further east. The elevated Sirat Expressway crosses Soi Ratchawithi 6 near the canal. The area is densely urbanized containing a mix of single-family homes, shophouses, and many small affordable dormitory apartment buildings for workers and students.

https://youtu.be/4UaXrJGrDmk

Video of Bung’s 5-minute walk along Soi Ratchawithi 6

Soi Ratchawithi 6 is crowded with local shops, supplemented by many street vendors, some conducting business from the back of pick-up trucks. All this retail activity supports the workers and the students living in small, single-room apartments along the soi. It is a pedestrian-friendly space with motorcycles occasionally weaving through. Vending and advertising trucks give way to occasional cars for the few single-family residences that still line the soi. Residents, outside of these few family houses are not car owners, so motorcycle taxis drive clients to nearby mass transit spots.

Toon’s walk down Soi Sawasdee, Sukhumvit 31

Soi Sawasdee lies north of Sukhumvit Road, a main commercial corridor of central Bangkok. It can be also accessed from Asok Montri and Petchburi Roads, while also connecting to multiple other sois, such as Sukhumvit Soi 23, 31, 39, and 49, all the way to Sukhumvit Soi 51, known as Thong Lor. The Asok Skytrain stop is just a short motorcycle taxi ride away. Toon has witnessed rapid development in the past decade that she has been living here. She observes that there is a wide range of different levels of income and expenses on this soi, and it is truly an “interstitial space”.

Walking east, on the right-hand side, is a relatively expensive sit-in restaurant which has recently set up a takeaway booth offering cheaper prices to help people out during the pandemic. On the opposite side of the road are commercial shophouses which are mostly medium to high-end restaurants. Visitors usually come from more distant areas, but now mostly delivery motorcycles can be seen here. On the right is a government school called Sawasdee School, so the 7-11 and the street food vendors are usually packed with school kids during after-school hours. A large number of parents of this school ride motorbikes, so there are street barriers set up for dropping off students. Despite the density of tall condominiums, the heat island effect is not very severe here as there are a lot of family homes with mature trees. There is also a small canal, roughly a meter wide, running parallel to the soi.

https://youtu.be/ex4f8WgtRnI

Video of Toon’s 5-minute walk along Soi Ratchawithi 6

Further down the soi, there are three interconnected, made-to-order, street food vendors open daily from 6:00 AM to 1:00 PM, except Mondays, when they are prohibited. The local motorcycle taxi station is located across the street, serving residents, school kids, and teachers. The inhabitants of the soi are reflected in the mixture of restaurants serving Thai, Western and Japanese food. On the right is a construction site for yet another high-rise condominium that has been in the process for the last three years. Around 5:00 to 6:00 AM when workers commute here for work there is a large flux of bicycles.

The drainage of the soi has always been problematic, and during rainy season it always floods so every entrance to a shop or a compound will have a slope up to prevent water from entering the property. At the end of the walk is a plastic bottle collector, who comes once a month. On the right is a high-end, high-rise condominium that just opened last year, while on the left is a French bakery and patisserie shop. The flux of visitors typically come from Thai youth who appreciate the European look of the shop and the authentic pastries.

3. Four Ecological Hot-Spots

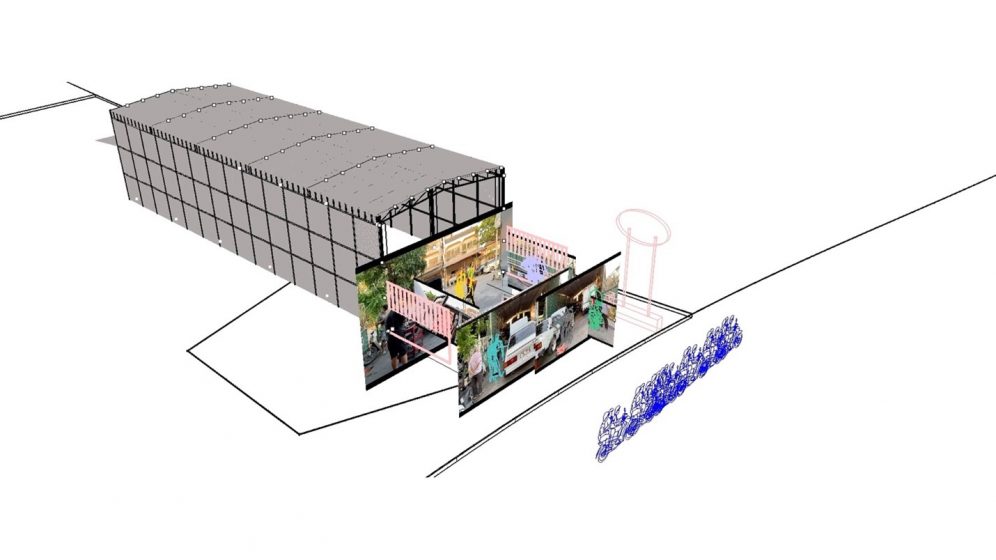

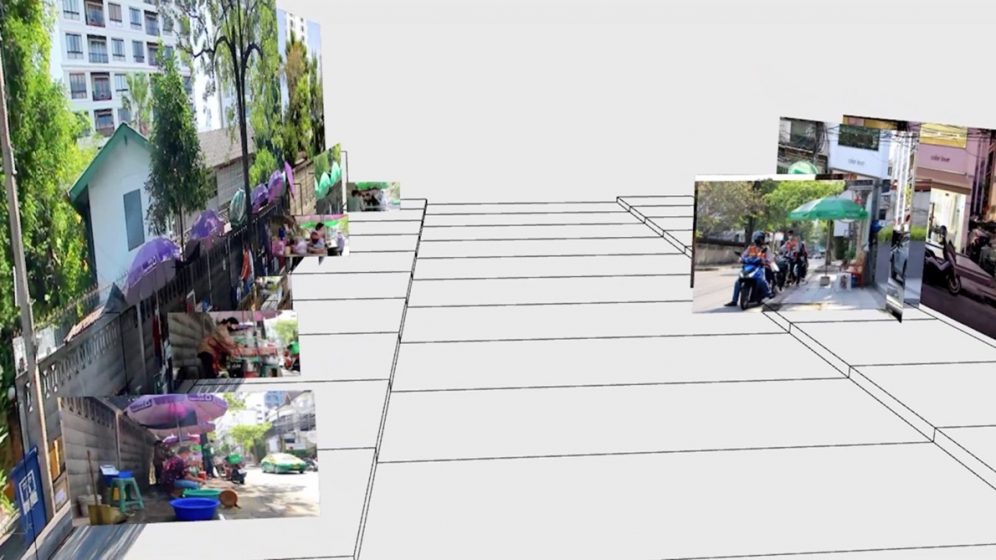

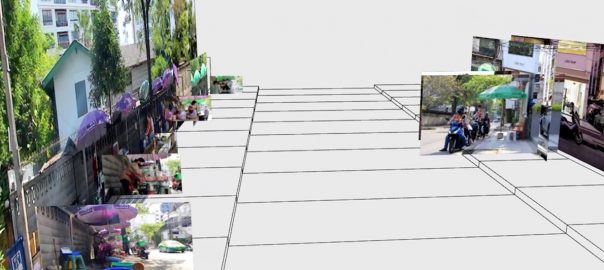

The second phase of the workshop furthered the ecological study of a soi by applying the Cinemetrics multi-dimensional approach to examine micro-level studies of one ecological “hot spot” on each soi. Through systematic video framing, soi hot spots were systematically “scanned” or “sensed” over several daily cycles in order to compile robust qualitative and quantitative data sets. Students videoed a hot spot from three angles at a close, medium, and long-range according to the multiple still framing technique of Japanese filmmaker Yasujirō Ozu. From this information, an interactive 3D digital model was constructed that could also visualize changes over time. Like corresponding architectural drawings plans, sections, and elevations, video frames are seen as 3D data, framing space, but also the transformation and flux of energy, matter, and information, which constitutes the ecological metabolism of the soi.

Car Repair Shop, Soi Phetkasem 88

As Hong noted in her walkthrough, the presence of car repair shops has emerged as a distinct characteristic of Soi Phetkasem 88. These shops play an integral role in the ecological interactions on this soi and are hot spots of social, material, and informational flux. Cars are parked on the soi, and the mechanics cooperate with local convenience stores and food vendors nearby and offer their expertise to the local residents. The interaction of this ecosystem includes a complex social pattern of both the cooperation of the businesses and among the residents of the soi.

Hot-spot video of a car repair shop, Soi Phetkasem 88

Hong documented the affection and attention that the mechanics have for their work. They demonstrated expertise in repairing motorbikes, trucks, racing cars, antique cars, as well as small motor parts. The car repair activities sometimes pollute the soi with oily residues and aerosol spray painting. However, the social care offered by the workers in these shops seems to offset the toxic residue for their soi neighbors.

The auto repair and the convenience shop workers, as well as residents, demonstrate these caring relationships that were built up over time. This explains why people do not complain much about polluting activities such as spray painting or oil changing. Even though there are residues, wastes, as well as some toxic substances being left behind, other businesses such as restaurants, grocery stores, hairdressers, and cafes are able to thrive due to the influence of the repair shops as it becomes an active hub for automotive work.

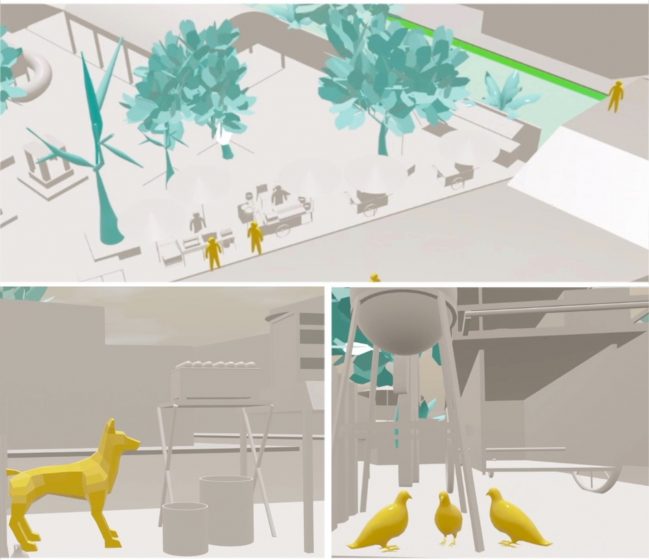

Afternoon Market, Soi Sinsapnakorn

With the opening of a new connecting road, an afternoon market has emerged next to the Soi Sinsapnakorn community play and sports area at the Lam Phakchi Canal bridge. Vendors wait for the temperature to drop in the early evening to prepare snacks and take-away meals for students after school, residents out for exercise, or people returning from work. There is a cooperative and complementary spirit among the vendors as each specializes in one course, beverages, or dessert, but they share a seating area and customers.

Video of afternoon market at Soi Sinsapnakorn

Oat observed only exercise activity in the park during his first morning walkthrough, but by returning at different times of day, he was able to document the vendor’s preparation and clean-up, and the portable architecture that they deploy. Interestingly, Oat observed not only human activity at the market, but the relationship between the vendors and the customers with street dogs and birds. Many people fed dogs table scraps, and pigeons and sparrows enjoyed overlooked crumbs on the ground.

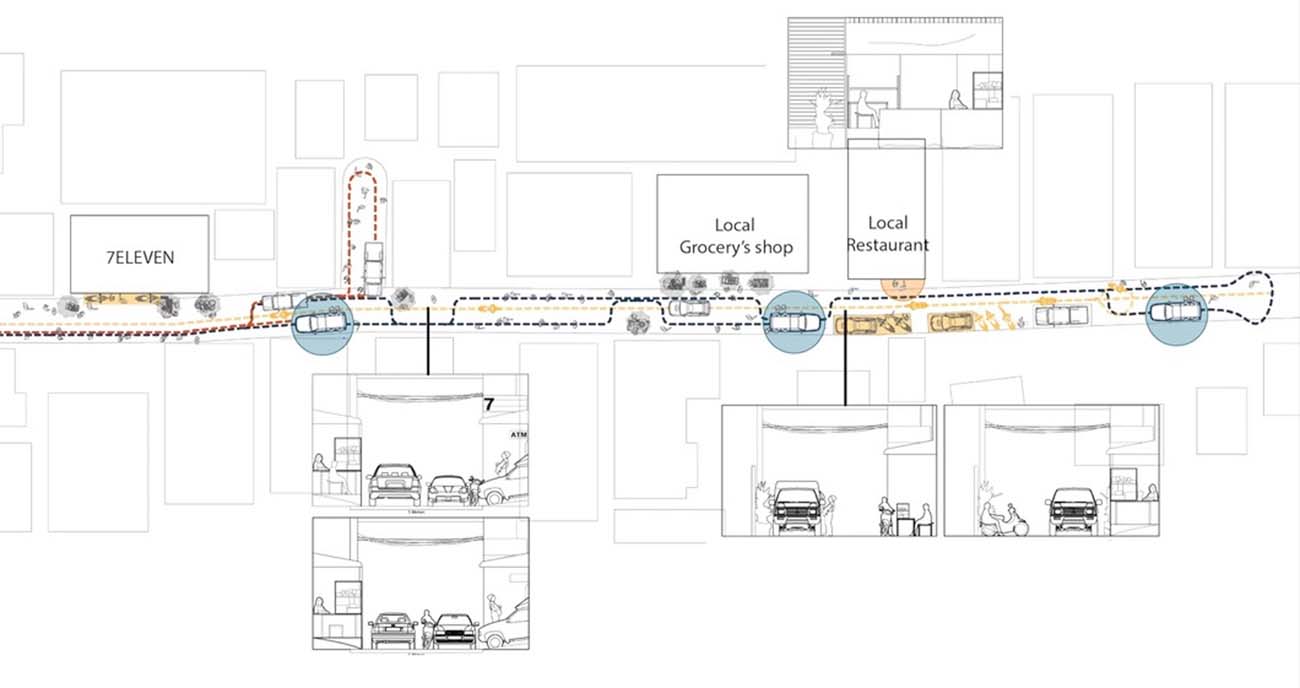

Street Vendors in Soi Ratchawithi 6

Bung’s morning walk through Soi Ratchawithi 6 showed the leisurely pace of a few students picking up some snacks for breakfast. However, in returning over the course of the day to a particularly dense concentration of mobile street vendors, he was able to document the tightly packed choreography of pedestrians, pick-up trucks, motorcycle taxis, and cars. Soi Rachawithi 6 is a narrow soi that effectively slows vehicular travelers down, as there is no way to quickly traverse the lane in a direct line.

https://youtu.be/cUFd7L4XaU4

Video of street vendors on Soi Ratchawithi 6

From his video over the course of several days, Bung was able to map the dance between the moving parts in the soi and even document how residents help to direct traffic during times of peak activity. In addition to slow traffic, the soi is also a place to enjoy slow food. Bung’s video documents how each dish is freshly prepared according to the customer’s direction – spicy, sour, sweet, or salty.

Cross-soi cooperation on Soi Sawasdee

Soi Sawasdee, like most of the sois off Sukhumvit, has many high-rise condominiums and commercial buildings as well as older detached houses with gardens, town and shophouses, and construction sites for even more towers. One particular cross-section of the soi, just south of the school, is especially active. A row of three food vendors work opposite a motorcycle taxi station. Both provide essential services to inhabitants and workers in this area, but they also help each other out, exchanging labor, on the part of the motorcycle taxi drivers, with food and drink provided by the vendors.

Video of sidewalk food stalls and motorcycle taxi stand on Soi Sawasdee

There are two food and one drink stall with some seating areas on one side, sharing several sun-shading umbrellas. They have an interconnected relationship with the motorcycle taxi drivers on the opposite side. Some drivers help the food stalls set up at 4:00 AM in trade for lunch. People in this area are regular customers for both services, commuting to-and-from the Skytrain with the bikers, and crossing the road to get lunch with the vendors. The food vendors have everything you’d crave in a made-to-order meal. Aunt Jong has a papaya salad shop and another station grills pork neck on a little gas top. On the opposite side, the motorcycle taxi station uses matching green umbrellas. The water tank behind the drivers also gets refilled by the food vendors.

Some customers have built a close relationship with the food stall owner, even dining on the table with cooking utensils to have casual chitchats with Aunt Jong. She hosts a true “chef’s table”. Later in the afternoon, around 2:00 PM, when there are no more customers, the vendors will start to pack up. Dishes are cleaned in the basin by the station. Umbrellas are knocked on the ground to remove leaves. Then everything gets put away through the gate to the house behind the fence, where one of the stall owners lives and works as a maid. Heavier things are packed and rolled away on a cart, again with the help of the motorcycle taxi drivers. Only the drink stall remains for a few more hours, and a couple of motorcycle taxis still operate late into the evening.

Conclusion

Parallel to the concerted efforts by global alliances and nation-states to confront the twin crises of climate and inequity, there are countless undocumented micro acts of ecological stewardship and social cooperation. Any locality can be seen as a spatially and temporally heterogeneous social-ecological system, and as such, can be analyzed as a hot spot of the potential integration of the architecture and ecology of the city. The metacity framework, explored in the Ecology of a Soi workshop, introduces ecological concepts into everyday architectural contexts in order to begin the process of coordinating and quantifying everyday transformation and flux of energy, matter, and information as important contributions to a just climate transition.

The students’ video data gathering captured the spatial and temporal distribution pattern of human and non-human organisms (plants and animals), their aggregation/abundance, as well as the bidirectional relationships between organisms and flexible self-built environments. They also measured the flux/flow of information, energy, and matter with a focus on processes, interactions, and relations. We present this distributive architectural system of local urban ecological data gathering as fundamental in collectively addressing the twin crises of social justice and climate change. It suggests that we stop seeing cities in terms of centers and peripheries, a residual concept of colonial metropolitanism, but as patchy distributive ecological systems, where every point in the system has equal value.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank INDA Program Director Surapong Lertsithichai, Deputy Director Sorachai Kornkasem, and Third Year Coordinator Scott Drake, as well as the students who participated in the workshop, Aticha Thanadirak, Pattraratee Keerasawangporn, Buris Chanchaikittikorn, Pittinun Tantasirin, Nichaporn Atsavaboonsap, Pheerapitch Phetchareon, Nisama Lawtongkum, Nicha Vareekasem, Raphadson Saraputtised, and Pannathorn Amnuaychokhirun. Special thanks to Dr. Steward Pickett for the many fruitful discussions about integrating the architecture and ecology of the metacity.

Brian McGrath and Vineet Diwadkar

New York and Bangkok

about the writer

Vineet Diwadkar

Vineet Diwadkar is a designer and urban planner working at the intersection of technology, ecology and policy. He is currently Associate Director with AECOM, Primary Investigator with the Terreform Center for Advanced Urban Research, and Adjunct Faculty at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok. Vineet works with communities, governments and multilateral organizations, infrastructure owners and operators, and researchers to deliver strategic planning and policy, cross-sector infrastructure and development, and to strengthen livelihoods through ecological and heritage conservation.

Leave a Reply