The COVID-19 pandemic is slowly receding and, while it still is a fatally serious problem in some places, it is possible to imagine it at least receding into an endemic disease. It is perhaps, therefore, a good time to reflect on what COVID-19 has meant and will mean for urban form and urban nature. In a previous post on TNOC, my coauthor and I argued, among other things, that the effects of COVID-19 on urban form were likely to be transitory. I was wrong. What seemed like a sensible argument in 2020 now doesn’t make sense. The COVID-19 pandemic persisted long enough to accelerate existing trends, leading to what appears likely to be persistent changes in urban form.

The simplistic version of the story is that COVID-19 led people to abandon cities for rural areas. I believe this simplistic version of an urban to rural migration to be a myth, with little support in the empirical data. The popular press sometimes equates “city” with the dense cores of major metro areas, or just focuses on major metro areas and their population trends. But when you look at urban areas as a whole, the fundamental trend does not seem to be migration to rural areas, but migration within and between urban areas.

Moreover, this migration seems to apply only to a few. Only about a quarter of workers in the US can work fully remotely, a figure that is likely much smaller globally. For these “knowledge workers” (a similar but broader set of people than Richard Florida’s famous formulation of the Creative Class), it was surprisingly possible to work remotely from their homes. However, many more workers have place-based jobs, jobs that must occur in a certain place, either because they are service jobs (e.g., wait staff in a restaurant) or because of centralized facilities (e.g., factory workers). The discourse then about COVID-19 leading people to abandon cities only applied to a small slice of (relatively well off) workers.

One unexpected effect of the COVID-19 pandemic was long-distance migration between urban areas, and sometimes between countries. This is best understood as families “going home” to solve problems associated with COVID-19. This could involve returning to family after the loss of a job, to save on the cost of housing. Or it could be, for instance, moving closer to relatives to deal with a lack of childcare caused by the widespread closing of daycare and schools. Whether these long-distance migrations are temporary or permanent is unclear but, at least in the short-term, the usual directions of global immigration reversed. Indeed, new immigration (away from relatives to a new country) appears down in most places.

My family is an example of such a long-distance migration home. While my wife and I thankfully held on to our jobs during the pandemic, two-income families like ours in the U.S. faced a severe childcare crisis. Schools were closed for in-person instruction for almost 18 months, leaving parents with the challenge of working remotely while also serving full-time as teacher’s aides and IT consultants. There was a sense of the U.S. society falling apart, of each family being left to fend for itself. For my French wife, there was some envy of how quickly French schools reopened compared with American ones, and a newfound respect for how difficult it is to be separated from one’s family by an ocean when borders begin to close. Moreover, our (now former) city of Washington, DC, was a particularly difficult place to weather the COVID-19 pandemic. Between civil unrest and an attempted coup on January 6 (2021), it was a grim time to be in the nation’s capital. My family and I ended up taking an opportunity to resettle in the Basel area. I am grateful for the opportunity, and the flexibility of my employer in allowing me to work remotely in the same job. Our family ended up moving from the Washington, DC metro area (population 6.3 million) to the Basel metro area (population 600,000), closer to my wife’s family (although farther from mine).

Our story is but one example among millions of stories of families responding to COVID-19. On average, prior immigrants tended to return to their home countries. There was a movement also from large to small metro areas. In the US, for instance, there was a movement away from big city metros like New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, and an acceleration of a preexisting trend toward growth in small metro areas in the South and West of the US. There was also an uptick in people settling in smaller towns and cities that have low costs of living but natural beauty, like Bozeman, Montana. Conversely, there does not appear to be a strong migration from urban areas to rural areas, per se. We might predict, then, that a consequence of COVID-19 globally, at least in the short to medium term, is a slowing of the growth rate in the world’s largest and most dense cities, but an acceleration of growth in small and medium-size urban agglomerations.

Perhaps more common than long-term migration is a shift within urban areas. One can move 50km out of a core urban area, to areas that are much lower density exurbs, and still be within the broader metropolitan area, as defined by commuting trends. For instance, a team member of mine moved to West Virginia rather than being near company headquarters, but may still be within the Washington, DC, metro region, as defined by the US Census Bureau. We might predict, then, that COVID-19 globally has led, at least in the short to medium term, to relatively faster growth rates in far suburbs and exurbs, and relatively slower growth rates in center cities.

One primary driver of this migration within urban areas was the need for more space in housing. City centers have more economic possibilities, for jobs and consumption, but they also have more expensive rent, which leads to smaller sizes of housing units. Households always balance the pros and cons of proximity to urban centers. The COVID-19 pandemic appears to have accelerated significantly an already existing trend toward increased telework. This drastically increased the time we all spent at home, increasing the value of having more space at home. To an urban economist, then, it is a very rational response to move farther from city centers, and get more space at home, if proximity to the urban core is no longer as important. Whether this is permanent or temporary depends on employer’s telework policy but, it should be noted that, in a sense, COVID-19 simply accelerated a transition that has been going on for much of the last century, of decreasing urban densities in metro areas.

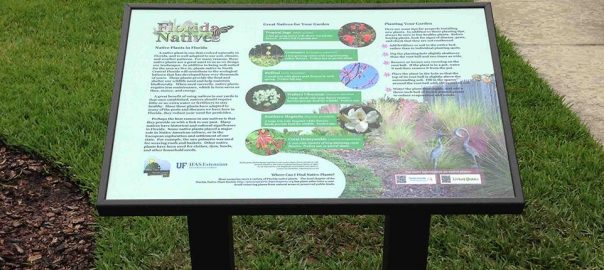

Another driver, at least anecdotally, of this move to far suburbs or exurbs is a desire for more parks and nature nearby. A large body of hedonic research shows that proximity to parks and natural areas is an amenity people are willing to pay for during normal times, and health researchers find physical and mental health benefits of time in nature. The COVID-19 pandemic, by reducing other entertainment options, appears to have increased the premium people are willing to pay to be located near natural areas, and this increased access may have been easier to obtain in rural areas. There is also some evidence that desire to access nature during the pandemic was increased, and there is even some evidence that those who have more access to nature are less likely to develop cases of COVID-19. I am hopeful that the desire to be near natural areas that many felt during the pandemic, as well as the rhetoric of policymakers around a “green recovery” to COVID-19, will lead to many communities (small and large) investing more in parks and open space.

While this shift to far suburbs and exurbs appears economically rational, it may have real negative consequences for the natural work. We might predict increased habitat conversion at the fringes of metro areas, as the real estate market responds to increased demand. We might predict increased vehicle kilometers traveled and increased GHG emissions, especially if remote working ends and commuting for knowledge workers restarts. For those now working remotely from a long distance, there is the potential for increased air travel. There is an analogy here to the invention of the Internet, which enables more remote teams but also led to increased business travel- teleworking appears to be a complementary good for physical travel, rather than a substitute.

As the joke goes, predictions are always hard, especially when they are about the future! But that caveat said, it seems likely to me that the increased tolerance for telework mostly persists. We will still live in an urban world, but a less dense, more diffuse one. The world’s urban network may be a bit more polycentric rather than having an intense concentration of talent in an industry in just a few metro areas. For those with place-based jobs, however, urban areas will face a prolonged period of transition, as firms adjust to the new distribution of customers. It is still an urban world, but COVID-19 has altered its form.

Rob McDonald

Basel

Banner image: Street dining in Brooklyn in the shade of a street tree. Photo: Erika Svendsen

Add a Comment

Join our conversation