Faced with the growing threat of extreme heat, cities everywhere need to plan for urban heat resilience — proactively mitigating and managing heat across urban systems and sectors. Here are seven key principles and eight strategies or urban heat resilience.

Cities everywhere are getting hotter. Globally, every year from 2013 to 2021 ranked among the 10 hottest on record due to climate change. Urban areas are generally warming at a faster rate than rural or natural areas due to the urban heat island (UHI), a phenomenon whereby the built environment and waste heat lead to increased temperatures.

Risks of both chronic heat and extreme heat events (e.g., heat waves) are growing and negatively impacting communities in a variety of ways. First and foremost, heat kills. In the United States, it is the number one weather-related killer. It also affects quality of life, local economies, energy and water use, ecosystems, infrastructure, and agriculture. In a recently published study, we surveyed a diverse sample of planners in cities across the United States about heat. Over 80% of planners reported experiencing some heat impact and a majority of planners were at least somewhat concerned about heat.

It is also clear that heat exposure and vulnerability are inequitable. Heat disproportionately affects marginalized communities and intersects with other systemic inequalities related to environmental quality, workplace safety, housing, energy, transportation, and healthcare.

Faced with the growing threat of extreme heat, cities everywhere need to plan for urban heat resilience – proactively mitigating and managing heat across urban systems and sectors. Yet, compared with other hazards like flooding, heat governance, or the actors, strategies, processes, and institutions that guide decision-making for mitigating and managing heat as a hazard are underdeveloped. Our research suggests that few studies have examined heat planning and governance. In most cities, it is unclear who is responsible for addressing heat. But this may be changing, as a few cities, including Phoenix, Arizona, and Miami-Dade County, Florida, have recently appointed heat officials.

In order to help elevate awareness of heat risk and inform heat planning in cities, we recently published a new Planning Advisory Report for the American Planning Association entitled Planning for Urban Heat Resilience. This report, which is freely available to download thanks to a grant from the NOAA Extreme Heat Risk Initiative, explains the complexities of heat and outlines an actionable framework for holistically planning for heat resilience.

A framework for planning for urban heat resilience

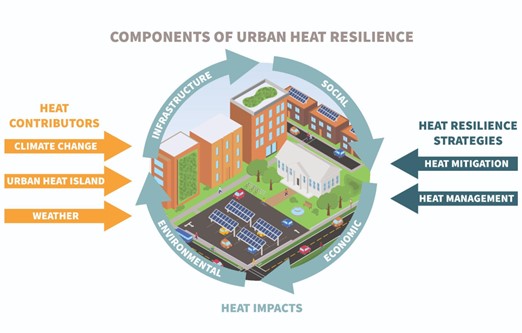

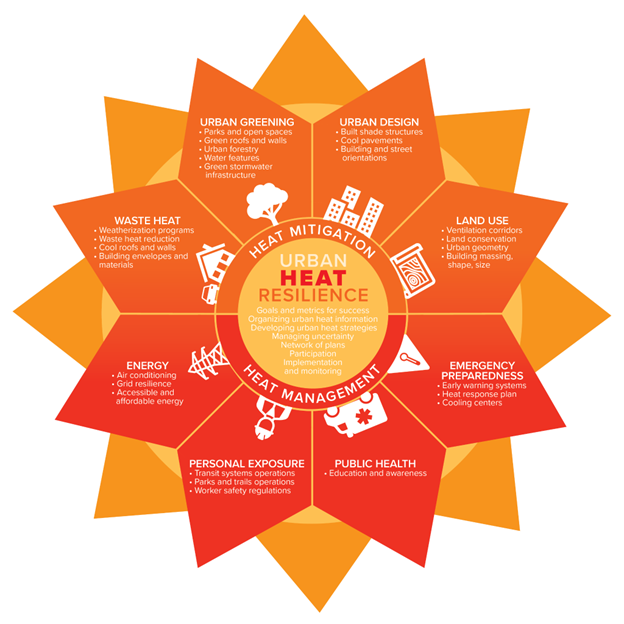

In our framework, planning for urban heat resilience means setting clear goals and metrics of success for both heat mitigation (cooling communities with vegetation and design of the built environment) and heat management (preparing for and responding to chronic and acute heat risk that cannot be mitigated). This requires a comprehensive “fact base” of information on current and future heat risk. Cities then need to develop a diverse portfolio of heat mitigation and management strategies, which should reflect future uncertainties. These efforts should be coordinated across different departments, sectors, and plans. And these strategies need to be implemented, monitored, and evaluated over time since heat planning is new in most communities.

When it comes to selecting heat resilience strategies, cities have a variety of options. We group these into eight categories, half of which are focused on heat mitigation and half on heat management.

When it comes to heat mitigation, the most commonly used strategy in the United States is urban greening, including urban forestry, green stormwater infrastructure, and other vegetation. But there are many other strategies that could mitigate heat including land use, urban design, and waste heat reduction. For example, efforts to enhance walkability and reduce vehicle use and building energy efficiency upgrades can also reduce waste heat.

Heat management strategies include policies and programs that focus on energy, particularly ensuring that residents have access to reliable and affordable indoor cooling, strategies geared towards reducing personal exposure to heat, public health, and emergency preparedness. Many communities are preparing for heat emergencies with early warning systems and cooling centers where people can shelter and seek assistance. Still, more emphasis may be needed on regulation to limit exposure and ensure that everyone can afford and access reliable indoor cooling.

Coordination is key

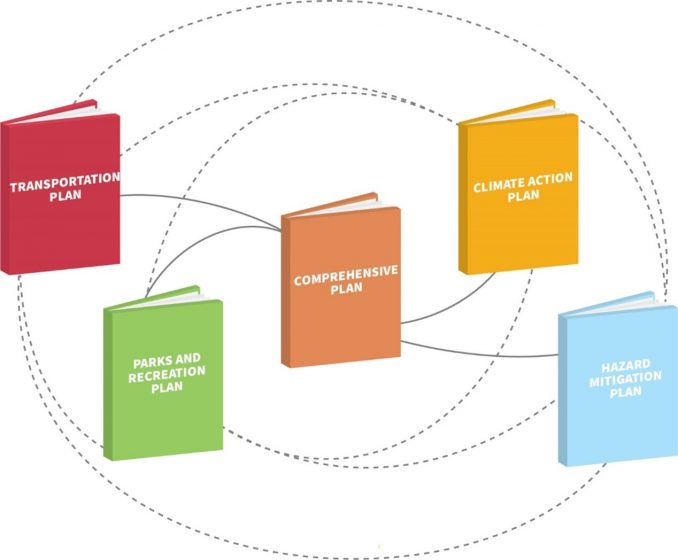

Effectively planning for urban heat resilience and implementing strategies will require that cities coordinate efforts across different disciplines and sectors, including planning, hazard mitigation, emergency management, public health, public works, parks and recreation, the energy sector, and many more.

Heat should also be addressed in all of the different community plans that shape the built environment and urban services — the network of plans. Thanks to the same NOAA grant that made it possible for the PAS Report to be free to download, we are also leading the development and piloting of the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard for Heat (PIRSH) methodology. PIRSH will allow planners to spatially analyze how different plans would affect heat risk and to identify policy inconsistencies. For example, one plan may call for additional vegetation to cool a particularly hot neighborhood, while another plan increases surface parking lots which could increase heat risks. We will publish a PIRSH guidebook and the Baltimore, Boston, Ft. Lauderdale, Houston, and Seattle pilot reports soon.

Time to act

All heat deaths are preventable, yet heat impacts will continue to increase unless cities around the world plan for urban heat resilience. Although heat governance remains fragmented and is still in its early days, we see promising signs that more communities are beginning to acknowledge heat as a hazard and take action.

Sara Meerow and Ladd Keith

Tempe and Tucson

about the writer

Ladd Keith

Ladd Keith, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the School of Landscape Architecture and Planning at The University of Arizona. An urban planner by training, he has over a decade of experience planning for climate change with diverse stakeholders in cities across the U.S. His current research explores heat planning and governance with funding from the NOAA, CDC, and National Institutes for Transportation and Communities.

Leave a Reply