At the end of November 2021, spending a few days in London, I paid a far too brief visit to the Natural History Museum. I had devoted the daylight hours to a survey of the skyscrapers burgeoning in the City’s business district and got to the museum just as the pale sun was slipping under the horizon, with the wannest of autumnal curtain calls. Just a first peek, so to speak, to get a feel for the place … in the hope that some future, hypothetical opportunity would offer up a more ample occasion for perusing its collections. The kind of visit-on-the-run where the harried contemplation of portions of exhibits has to be executed on the double.

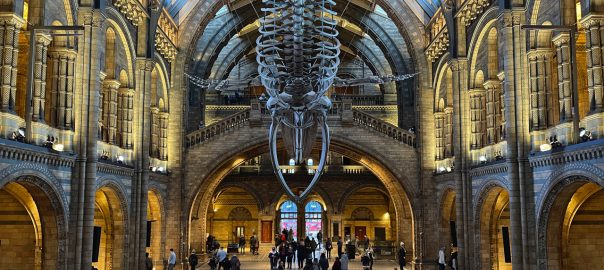

One enters through Hintze Hall, the museum’s architectural centrepiece, a Gothic Revival-cum-Romanesque cathedralesque space under a skylit, metal-arched roof, attesting to its construction in the nineteenth century. The deep alcoves on both sides, the high-flung first-floor balconies, are populated with the display of a host of animals, vegetables, and minerals – their remnants, to be more precise—spectacular highlights from the museum’s collections. The whole is riotously ornamental, the hall’s ceiling panelled with gilded illustrations of plants; the entire building’s interior and exterior abounding with terracotta sculptures of manifold forms of life, animals particularly, existent or extinct. The skeleton of a blue whale hangs from the roof, the bones gently bathed in blue light, in case you don’t get the point.

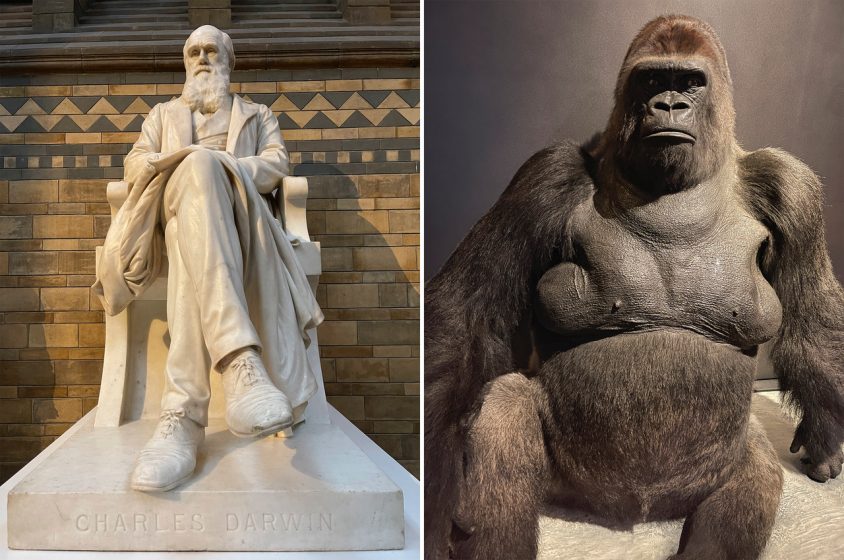

That the museum should be a cathedral—a cathedral to nature—was at the heart of its founder, Sir Richard Owen’s, intent. And indeed, at the further end of Hintze Hall, where one might have expected an altar, a broad flight of steps goes upwards to a landing; and where might have officiated a priest, a statue of Charles Darwin presides, holding a watchful eye over the scientific corpus in which he played such an instrumental role. A reminiscence, vaguely so, of bearded God painted on some Baroque ceiling, ensconced in a cloud, overseeing the world.

Designed by Alfred Waterhouse, who was the mastermind behind its elaborate, naturalistic ornamentation, the museum’s Historicist style is characteristic of Victorian architecture. In incorporating previous styles, one wonders whether the British Empire endeavoured to take possession of time, just as it had so ruthlessly gone about taking possession of space[i]. As such, museums and collections surely served to materialise the appropriation of history, englobed within Britannia’s magnanimous fold. One almost expects Tarzan to come swinging from the roof trusses, the archetypical English gentleman who whitewashes the colonial-industrial complex with the image of unsullied nature.

For early twentieth-century Modernist architects, such stylistic pastiche was anathema. Architecture should express the honest authenticity of contemporary materials and techniques, no frills attached. “Form follows function,” said the American architect, Louis Sullivan (who was a brilliant ornamentalist, it might be added). It became a rallying cry; ornament had to go; it was aesthetically reprehensible—a kindred cry was “Ornament is crime!” This was Austrian architect Adolf Loos, for whom decoration incarnated the irrational pulsions of primitive societies, to which Modernity’s antidote was to be the scientifically enlightened blank wall.

Of course, form follows function—how could it be otherwise, singularly when one contemplates the creatures on display in this museum? If it were not so, how might an eagle fly in the sky, a salmon swim in the sea, a monkey swing through the trees?

And as far as ornamentation goes, examination of the myriad forms that life has taken—the exquisitely patterned plumage of birds; the fulgurant colours and shapes of flowers, and their fragrance too; the elegantly exoskeletal workings of insects—one is forced to recognise that decoration forms an axiomatic part of nature, that could never be dismissed as something superfluous. One has the distinct impression—looking at the fantastical, imaginative, ornamentally beautiful forms taken by nature—that however seriously natural selection managed evolution, seriously playful forces were at work. Forces that never gave a damn about adhering to some “natural” tenet in which everything is to be determined by rational necessity. As if reducing life’s forms to explanations based purely upon survival of the fittest, or upon guaranteeing the reproductive cycle, somehow don’t provide closure.

***

Going up the stairs, one comes face to face with the statue of Charles Darwin, seated with his coat splayed over his knees, surveying pensively (or so it seems) the ongoing repercussions of the revolution in the natural sciences that he launched in the nineteenth century.

Visitors from all over the world cluster around him, some turn their backs and take selfies, contorting their bodies so as to get the great man to gaze over their shoulders. And on occasion, wedding ceremonies take place in his presence, since Hintze Hall is available for hire for festive occasions[ii]. A publicity photograph on the museum’s website shows a table for two, presumably the bride and groom, placed literally at Darwin’s feet. One wonders whether this is to get his unction in favouring the perfect evolutionary outcome for their match.

Continuing up the stairs to the right of the statue, and turning left on the balcony, one comes face to face with a large hominoid, hairless chest jutting over a black-furred belly, eyes under protruding brow hidden in the shadows, mouth cast in a solemn scowl. A label tells us that this is (was) Guy the gorilla, London Zoo’s best-loved resident, a western lowland gorilla who lived from 1946 to 1978, immortalised at the taxidermist’s hand, and relocated to the museum.

Guy the gorilla was named for Guy Fawkes, for no other reason than that he happened to arrive at the London Zoo on November 5th, the anniversary of the failed Gunpowder Plot to blow up the Houses of Parliament in 1605. An infant, he had been abducted from gorilla society in the Cameroons tropical forest, at the demand of the Paris Zoo. He finally ended up in London, after being swapped for a tiger.

Guy is remembered for a morose demeanour, and the way he would fling himself around his small cage. Among zoo-goers, he became an all-time favourite, charmed by the contrast between his great size and peaceable nature (when he was not protesting against the size of his living quarters). He was known to carefully examine birds that alighted on his hands[iii].

Guy died from a heart attack while undergoing dental surgery, his teeth ruined by visitors who showered him with sweets. And supreme indignity, his epidermal envelope was taxidermized for display in a glass cabinet, body contorted into a pose for an everlasting instant of posterity. How would you feel, morally, if a flesh and bloodless, stuffed Charles Darwin—rather than a dignified representation in stone—greeted you as you came up the stairs?

Confiscating the existence of the likes of Guy the gorilla is the vocation of zookeepers the world over: incarcerate, enslave, put on display like an object, take possession of. As a form of subjugation, it is part of the toolbox of colonial exploitation, pillage, and servitude inflicted for the gratification of the masses back home. Guy may have been the darling of zoo-goers, the star who made the show pay. All he was “offered” was meaningless fame in exchange.

***

Many years ago, on a previous visit to London, on Saturday, 22nd September 2007 (to be precise), I encountered a crowd of gorilla-suited humans running across the Millennium Bridge. This was the annual Great Gorilla Run, an event organised to raise funds for gorilla conservation. Unknowingly, or perhaps knowingly, they were doing penance for how London had martyrized Guy.

Joseph Rabie

Montreuil

Notes:

[i] See article describing Alfred Waterhouse’s architectural project on the museum website, with drawings and photographs showing examples of the building’s elaborate ornamentation. And another article about the ceiling of Hintze Hall.

[iii] See BBC article by Richard Warry, June 1, 2016. Also see Guy’s Wikipedia page.

Nice one, Joe! One can sometimes – Home Alone-like – spend a night in the museum, and get to see what comes alive … 🙂