The vision is that all residents and visitors of southeast Michigan — people of all ages, backgrounds, ethnicities, abilities, and interests — are connected to these water resources, feel welcome on its trails, and share in the benefits and opportunities offered by access to water.

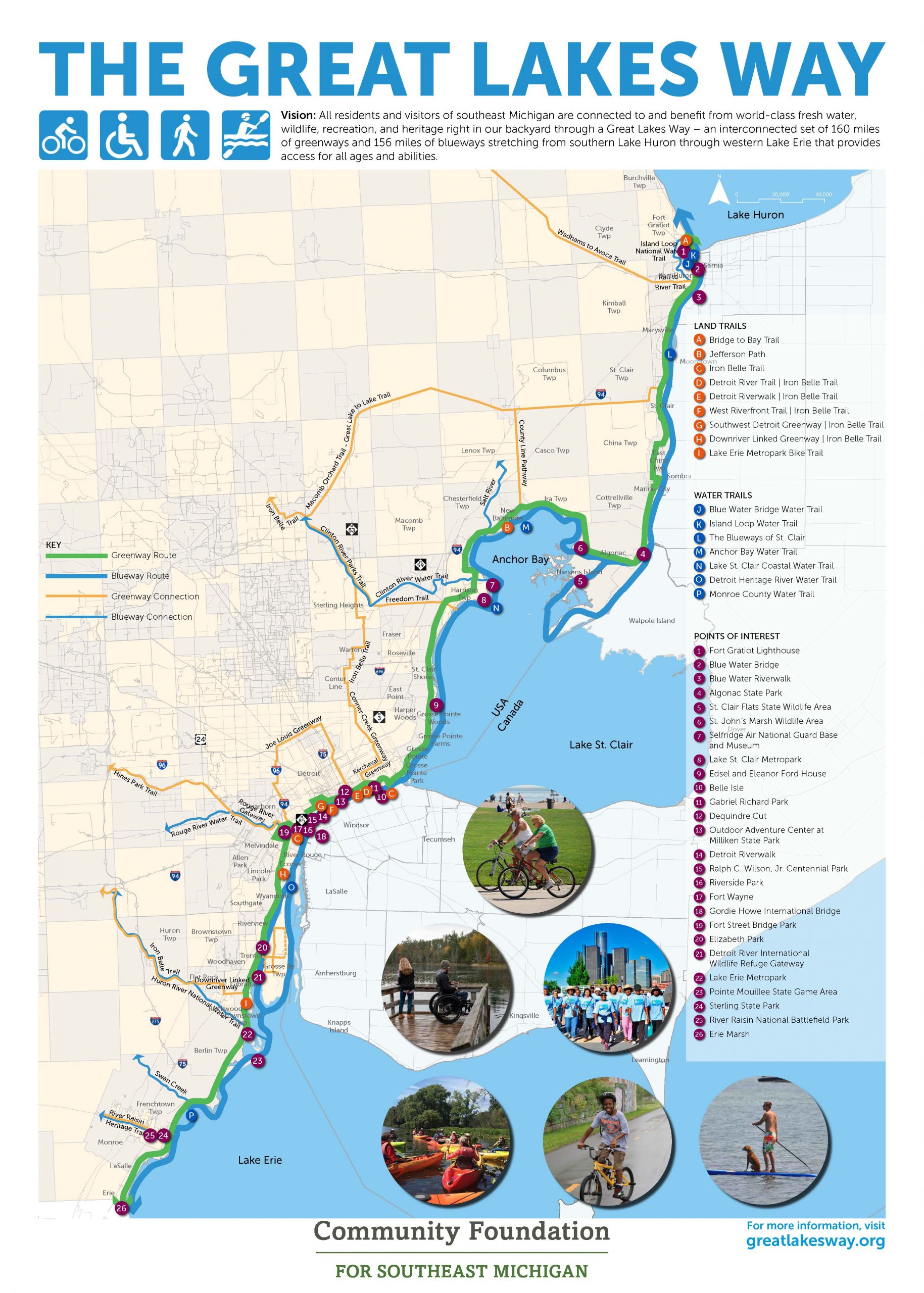

The portion of the Great Lakes basin ecosystem stretching from southern Lake Huron through western Lake Erie is a unique urban refugium where the tapestry of life has been woven with elegance, where the music of life has been rehearsed to perfection for thousands of years, where nature’s colors are most vibrant and engaging, where time is measured in seasons, and where outdoor recreation takes center stage. This region, better known as Metropolitan Detroit, is where the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan and many partners are knitting together 160 miles of greenways and 156 miles of water trails to become The Great Lakes Way.

Metropolitan Detroit is situated in the heart of the Great Lakes which represent one-fifth of the standing freshwater on the Earth’s surface. This Great Lakes Way is unique for its continentally significant natural resources and history, including Native American, Underground Railroad, shipbuilding, automobile manufacturing, Arsenal of Democracy, and more. Along The Great Lakes Way, you will find one of the largest freshwater deltas in the world – the St. Clair Flats, a Wetland of International Importance designated under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, four Important Bird Areas designated by the National Audubon Society, the only international heritage river system in the world – the Detroit River, the only international wildlife refuge in North America, a Regional Shorebird Reserve designated under the Western Hemispheric Shorebird Reserve Network, one of the three best places of watch hawk migrations in the United States, one of the top ten metropolitan areas for waterfowl hunting in the United States identified by Ducks Unlimited, and an internationally renowned sport fishery that attracts tournaments offering $500,000-$1.5 million in prize money. The Great Lakes Way traverses along or through 30 different federal lands, including a national park, 15 state parks or state game/wildlife areas, two metro parks, and 90 county and city parks. Together, these natural resources and recreational, historical, and cultural amenities provide a compelling outdoor experience for nearly seven million people living in the watershed and millions more annual visitors, an urban experience that is truly unique.

Building on the foundation of the GreenWays Initiative

For too long, many cities in Metropolitan Detroit could not make the match requirements on federal and state greenways grants. These communities simply did not have the discretionary funds, or parks and outdoor recreation did not rank high enough to get the necessary municipal funding to make the match on greenway grants. The solution was for the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan to raise this money from the private and foundation sectors so that more greenway trails could be constructed, and subsequently realize their many benefits. In 2001, the Community Foundation raised $25 million to create its GreenWays Initiative – the first of its kind in the nation – to help make match requirements on greenway grants. Over time, this initiative grew to $35 million and leveraged $150 million to build more than 100 miles of greenway trails. Standing on the shoulders of its GreenWays Initiative, the Community Foundation is now championing The Great Lakes Way.

Status of The Great Lakes Way

The vision is that all residents and visitors of southeast Michigan – people of all ages, backgrounds, ethnicities, abilities, and interests – are connected to these water resources, feel welcome on its trails, and share in the benefits and opportunities offered by access to water. All the water trails or blueways are complete and available for use. Preliminary mapping of greenways found that 64% are completed or partially complete, 25% are planned, and 11% remain to be completed. Through this initiative, the Community Foundation will be amplifying the important work of local trail organizations so that they don’t lose their identity and will be ensuring that they benefit from being part of a larger trail system. The Great Lakes Way will build on existing assets and programs, ensure broad equity, and put the Great Lakes Way into the consciousness of residents and visitors to the region.

No. 1 Riverwalk in the United States

As recently as the early-2000s, a considerable portion of Detroit’s waterfront land between the MacArthur Bridge to the island park called Belle Isle and the Ambassador Bridge to Canada was either abandoned buildings, underutilized street parking lots, material storage piles, or cement silos that prohibited access to the Detroit River. For over a century, city planners identified the highest and best use of this land to be “industrial” because of obvious revenue returns. Detroit was an industrial town, and it had a working riverfront that supported industry and commerce.

However, times had changed. There were fewer people and industries, and much underutilized and undervalued riverfront land. Detroiters had long lost their connection to the Detroit River, and they wanted to improve public access to it and redevelop it in a fashion that would improve quality of life, catalyze economic development, and help change the perception of Detroit from that of a Rust Belt city to one that is actively engaged in sustainable redevelopment.

Out of this growing public interest to reconnect to the Detroit River, the ecological recovery of the Detroit River, and strong public and private support to revitalize Detroit, the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy was created in 2003 to transform Detroit’s international riverfront – the face of the city – into a beautiful, exciting, safe, accessible world-class gathering place for all. Nearly three million annual visitors are already using it and, in each of the last two years, the Detroit RiverWalk was named the No. 1 riverwalk in the United States by USA Today. In many respects, the Detroit RiverWalk is a model for The Great Lakes Way.

Benefits

By any measure, the benefits of The Great Lakes way are impressive. Benefits include:

- promoting outdoor recreation – in Michigan, $26.6 billion is spent annually on outdoor recreation;

- catalyzing economic development – in its first ten years, the Detroit RiverWalk alone spurred approximately $1 billion of public- and private-sector investment;

- increasing adjacent property values – studies have found that homes close to a greenway have an approximately 20% higher mean sales price;

- connecting young people with nature – 80% of all people in the United States live in urban areas and many are still disconnected from nature;

- furthering conservation through habitat rehabilitation and enhancement – green infrastructure, pollinator gardens, stopover habitats for birds, and spawning and nursery habitats for fishes – and creating wildlife corridors;

- celebrating historical and cultural assets – the economic impact of MotorCities National Heritage Area alone is $410 million annually;

- supporting healthful living;

- improving quality of life; and

- connecting diverse people to each other and building community.

International Connections

Windsor, Ontario, Canada and Detroit, Michigan, USA are Great Lakes border cities on the Detroit River. Windsor has a long history of greenways dating back to the 1960s. In many respects, Windsor’s waterfront greenways were an inspiration to Detroit’s greenways that gained traction in the 1990s.

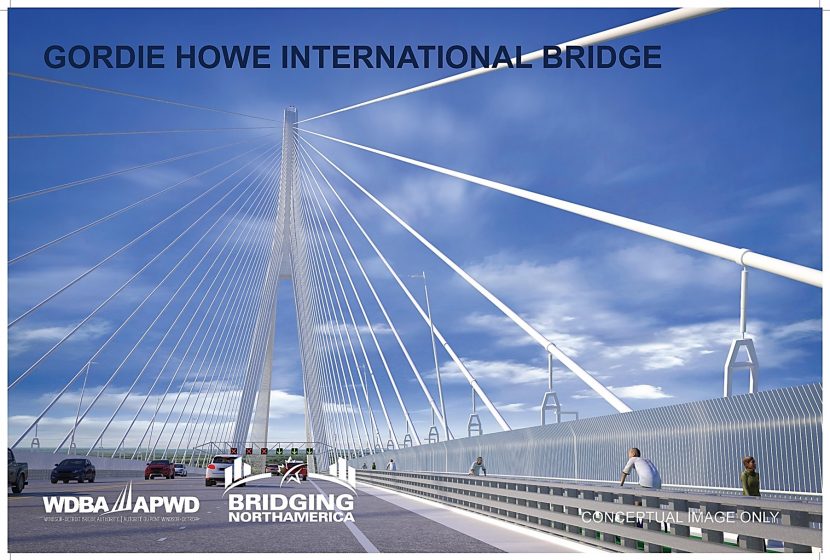

With the announcement of a new border crossing between Windsor and Detroit – the Gordie Howe International Bridge – greenway stakeholders came together to envision cross-border linkages and released a U.S.-Canada Greenways Vision Map in 2016 to connect emerging greenways. In response to this 2016 vision map, the Windsor-Detroit Bridge Authority committed to including a dedicated bicycle and pedestrian lane on the new Gordie Howe International Bridge, projected to be completed in 2024.

Detroit’s greenways are part of Michigan’s Iron Belle Trail that extends more than 2,000 miles from Ironwood, Michigan, located at the far western tip of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, to Belle Isle State Park in Detroit and The Great Lakes Way. Windsor’s greenways connect to Essex County greenways and are part of the Great Lakes Waterfront Trail that stretches along the shores of Lake Ontario, Lake Erie, Lake St. Clair, Lake Huron, and the St. Clair, Detroit, Niagara, and St. Lawrence Rivers from the Quebec border to Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario – a total of 1,865 miles. The Great Lakes Waterfront Trail is also connected to the Trans Canada Trail that stretches from the Atlantic to the Pacific to the Arctic Oceans – nearly 17,500 miles. It is the longest recreational, multi-use, trail network in the world.

When the new Gordie Howe International Bridge opens in 2024, these four trail systems will be connected, providing binational outdoor recreational experiences unparalleled in North America. Partners are now exploring joint outreach, promotion, and binational experiences.

Next Steps

The next steps for The Great Lakes Way include:

- engaging communities and putting The Great Lakes Way into the consciousness of residents and visitors via marketing, communications, community engagement, and outreach strategies;

- engaging with and providing support to under-served communities;

- building support and seeking additional partners;

- raising necessary funds to sustain the initiative; and

- strengthening transboundary collaboration on trails and exploring national and/or state trail designations to raise its profile and help ensure long-term sustainability.

John H. Hartig

Windsor

Leave a Reply