Aside from the huge number of swanky resorts and their reputation as a honeymoon destination, the Maldives is probably best known for their less fortunate status as the nation most under threat from climate change.

I recently had the great pleasure and privilege of a holiday on a boat in the Maldives. I had never sailed before, and am by no means an ocean-going character (indeed I took a year of swimming lessons in anticipation of this holiday), so the whole experience of being at sea was wonderfully novel to me and got me thinking about nature in all sorts of new ways. The Maldives is tiny, ranking the smallest country in Asia, and made up of over 1000 islands spread out over the Indian Ocean.

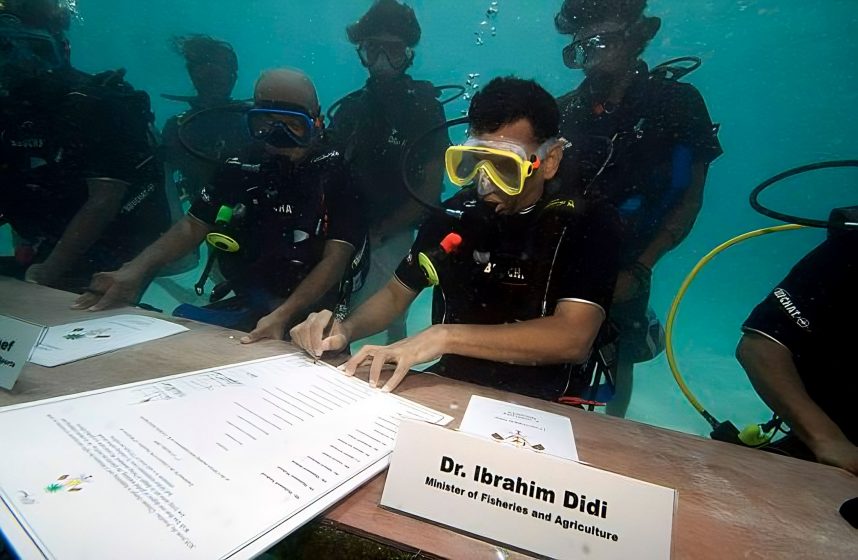

Their population is small, at around 533 900 people all living on a cumulative 298 km2 (115mi2) of land. Aside from the huge number of swanky resorts and their reputation as a honeymoon destination, the Maldives is probably best known for their less fortunate status as the nation most under threat from climate change. If scientific projections are correct the nation will be inundated by 2100. Their cabinet famously held an underwater meeting ahead of the 2009 U.N. Climate Summit in Copenhagen as a symbolic cry for help.

What I found revelatory about my trip however was far more basic and straightforward. It is that in the Maldives, and no doubt numerous other coastal and island places, urban nature for them is mostly underwater. Not only is the bulk of daily experienced nature underwater, but with climate change and associated sea-level rise, there is more of this nature encroaching all the time.

Many of the islands are so small that you can stand on the beach where you land and look down the main street right through to the ocean on the other side.

The proximity of the sea and life in the sea is astoundingly ever-present. And the beaches are littered with shells and in a few strides into the water you are surrounded by sea life. Roads are often compact sand, and when it rains, or the tide is high, this sand is wet giving the uneasy sensation of almost being underwater all the time.

It felt unclear to me where the sea ended, and the land began. It’s not to say there is no terrestrial nature. Indeed, there seems to be a concerted effort on the part of residents to grow what greenery they can, but this feels incidental compared to the vast nature presented by the surrounding sea.

While I might take a walk to my local greenbelt, or visit the neighbourhood park, it would seem to me any equivalent outing in the Maldives would involve a beach or the sea. I was delighted by an urban park that demonstrated exactly this, where a portion of the sea had been cordoned off at the end of a block and shaded gazebos set up on the sand for mothers who looked on while small children splashed about in the water.

Another city park has paths set among stretches of beach sand in the manner of paths crossing a public lawn.

Almost all nature in the Maldives is sea, sand, and ocean-related and this infuses many of their urban public park spaces.

So, what must it feel like when this nature, the nature you grow up with, the nature that fills your childhood parks, the nature you love, starts to encroach on your city? I try and imagine the terrestrial equivalent. I guess it would be living in a city and the trees and lawns start to creep closer to your house. Grass runners inching their way up the steps towards your front door. Saplings sprouting in your living room. It’s hard to imagine. But for the Maldivians this is reality. Climate change will almost certainly bring nature even closer, threatening their cities, towns, and lives.

The Sinamale bridge, and airport expansion, both being constructed by the Chinese, are among a number of large engineering projects that also appear to be shoring up the islands in anticipation of sea level rise. It’s an expensive project—as island building always is—and it’s hard to know how viable it really is. There is a lovely piece of urban nature-based graffiti beautifully and cleverly painted onto a street in Hulhumale, the airport island just next to the capital of Male, which depicts dolphins breaking through the street, with a wooden bridge across the divided, broken, and submerged tarmac.

This piece of art seems to suggest nature is revered, and loved, but also is a clear statement of panic and concern over sea level rise. The piece is striking. It says to the viewer the sea is just beneath us, and it’s about to get a whole lot closer.

I do acknowledge these musings are undoubtedly naïve. The brief insights gained are enough to let me know my reading of these landscapes is grossly limited. I can cast my eye across a public park or a nature reserve and have some sense of diversity and system health, but in this nature, I am at a loss. I am sure the sea presents textures and colours that are easily understood by locals and lost on me. I cannot imagine what living with this kind of nature must mean for one’s everyday life, but its beauty is readily evident, and the nature is breathtaking.

While I cannot claim an understanding of these seascapes, the experience has shifted my terrestrial thinking and turned me on my head. I look at my terrestrial landscapes now with greater depth. I think I see the air and the soil now in ways I did not before. I see my landscapes as immersed, embedded, upside down, fluid, and connected; less separate entities and more clines.

Pippin Anderson

Cape Town

Leave a Reply