En tant que paysage patrimonial avec de nombreuses années d’histoire, il semblait fondamental d’intégrer la fragmentation du Parc Jean-Drapeau plutôt que d’essayer de l’aplanir. L’idée était de reconnaître que le parc est un produit évolutif de plusieurs siècles, récupérant le sens perdu et affirmant l’identité.

Retrouver le sens perdu et affirmer l’identité du parc

Les parcs sont aujourd’hui une collection éclectique de strates de paysages aménagés et construits issus de multiples époques[1]. Autant pour ceux qui réalisent des parcs que ceux qui les conçoivent, il est à propos de se questionner sur la conciliation entre d’une part révéler et célébrer l’historicité des parcs et leurs composantes et d’autre part appliquer des approches actualisées de transformation pour en faire des parcs qui répondent aux besoins du XXIe siècle. Comment considérer les patrimoines qu’ils contiennent et représentent tout en laissant place à la production de nouvelles formes contemporaines?

Est-ce qu’une cohabitation des fonctions, des styles et des traces est possible et souhaitable? Comment répondre aux éléments de rupture et de désuétude tout en assurant une continuité identitaire du lieu? Quelles formes devraient prendre les parcs du futur? Ces questions ont informé l’approche conceptuelle du Plan directeur de conservation, d’aménagement et de développement du parc Jean-Drapeau 2020-2030 réalisé et dirigé par NIPpaysage, avec Réal Paul, architectes, ATOMIC3 et Biodiversité conseil.

Dans les dernières décennies, l’usage public du parc Jean-Drapeau a vécu une crise. Un éloignement et une distanciation se sont opérés avec les citoyens au point de faire du Parc un « landscape of estrangement » pour reprendre le concept de James Corner. Celui-ci critiquait la technologie et le capitalisme qui contribuaient à nous éloigner de la valeur poétique de l’architecture de paysage et prônait pour une conciliation de l’histoire et du sens du lieu avec les circonstances contemporaines. «Many fail to even appreciate the role that landscape architecture plays in the constitution and embodiement of culture, forgetful of the designed landscape’s symbolic and revelatory powers, especially with regard to collective memory, cultural orientation, and continuity[2]». Il convenait donc, à travers le processus de conception paysagère, d’œuvrer à positionner clairement l’identité du Parc pour lui redonner une cohérence physique, refléter ses valeurs culturelles et le réinscrire dans les pratiques citoyennes. Après avoir placé la conservation comme l’une des principales orientations stratégiques, sept principes d’aménagement ont été élaborés : positionner le Parc à l’échelle métropolitaine et régionale, célébrer le caractère insulaire du Parc, mettre en valeur le riche héritage patrimonial, mettre en valeur les paysages aquatiques et leurs écosystèmes, favoriser la diversité et la connectivité des écosystèmes, assurer le continuum d’expériences paysagères du Parc et miser sur les expériences de mobilité pour découvrir le Parc. En découla le concept d’aménagement qui répond directement à cette perte de sens et de contact, soit : «La célébration du grand parc insulaire grâce à la consolidation de ses rives et du cœur des îles Sainte-Hélène et Notre-Dame».

Le parc et le paysage comme destination paysagère et sociale

À la manière des parcs de Frederick Law Olmsted, la volonté partagée était de faire du paysage insulaire réinventé du parc Jean-Drapeau une destination en soi[3]. Citons en exemple Central Park, Millenium Park ou Governor’s Island où la qualité de l’aménagement a été, dès l’étape de planification, prévue pour être une attraction locale et touristique de premier plan. Le plan d’aménagement du parc Jean-Drapeau vise aussi à créer du vide, à laisser s’exprimer le design du Parc dans toute sa créativité. Comme le soulignait Bernard Huet : «We are afraid of emptiness. Afraid of void, of an empty, beautiful space[4]». L’importance de cesser de surcharger et de remplir l’espace d’installations temporaires de tout genre (panneaux de signalisation, barrières, clôtures, mobilier, arrangements floraux, plateformes, etc.) de même que de viser l’optimisation des paysages a largement fait partie des réflexions pour valoriser le site patrimonial, célébrer les legs en architecture de paysage et surtout contribuer à l’émergence de milieux habités. Comme l’écrivait Kate Orff dans The New Landscape Declaration : «Where the spaces can be reimagined as productive landscapes that are not only pastoral settings but also active generators of social life[5]».

Clare Cooper Marcus écrivait que: «Two frequently cited reasons for park use are: a desire to be in a natural setting and a need for human contact[6]», un constat toujours d’actualité aujourd’hui qui a informé tout le processus créatif. Celui-ci s’est également appuyé sur les «guidelines», «design recommandations» et «users’ needs ” élaborés par plusieurs auteurs au fil des ans, dont les critères de qualité pour les espaces fréquentés par les piétons de Jan Gehl, (2012), qui ont fait ressortir les éléments qui font le succès des espaces publics (successful features) (notamment Whyte, 1980[7], Cooper Marcus et Francis, 1990[8], Tate et Eaton, 2015[9]). La réflexion a été particulièrement soucieuse de répondre aux besoins et aux habitudes de tous les usagers et des communautés culturelles par un engagement envers la diversité. Divers auteurs ont en effet étudié les différences culturelles dans les attitudes, comportements et occupations des parcs; certains groupes culturels préférant davantage des rassemblements autour de repas ou une récréation passive et d’autres préférant le mouvement et la récréation active à titre d’exemple[10].

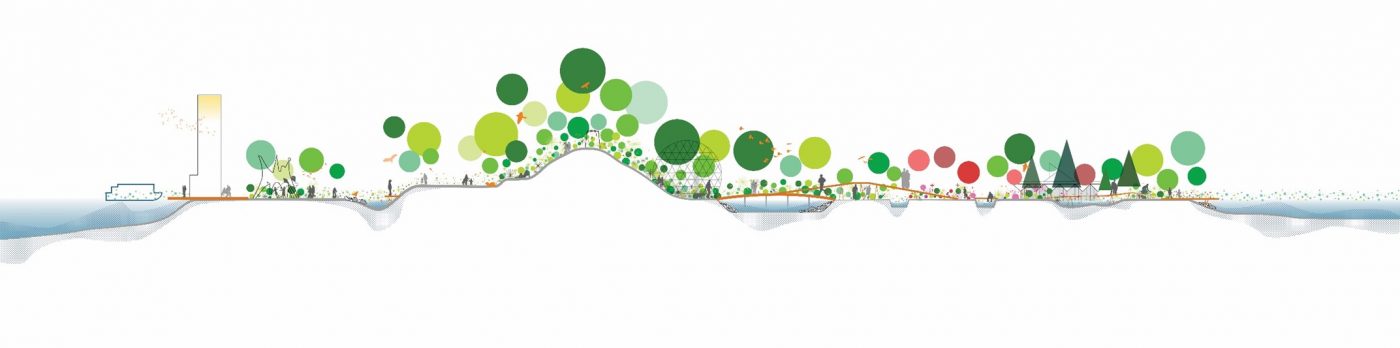

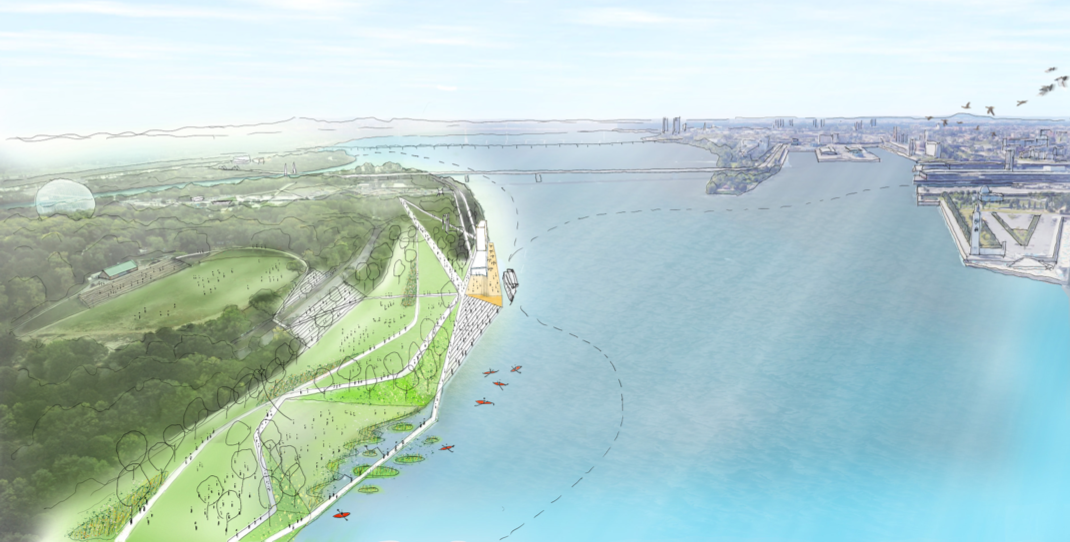

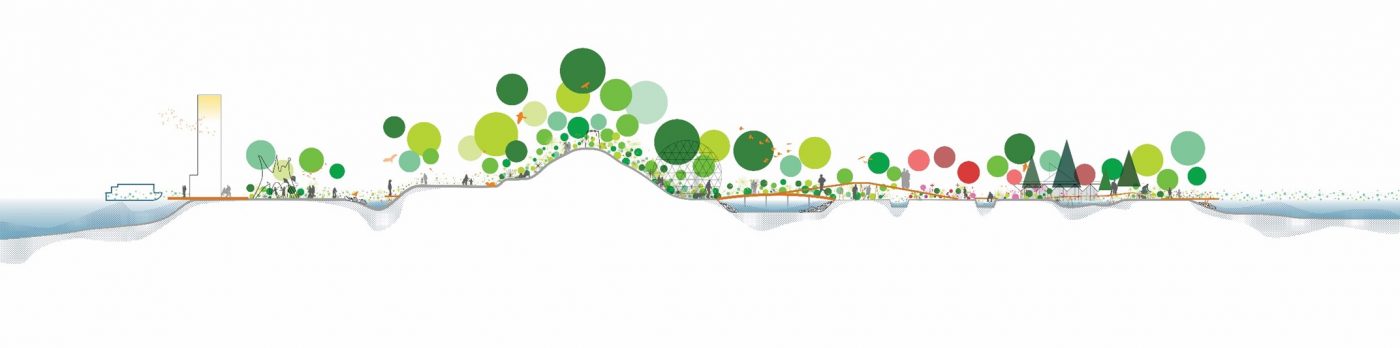

Ces connaissances issues de recherches scientifiques et d’observations terrain ont été sérieusement considérées afin de s’assurer d’une justice sociale dans l’accessibilité au parc (égalité, équité, inclusion). Dans The Politics of Parks Design, Cranz écrivait que le potentiel des parcs à façonner et à refléter les valeurs sociales n’était pas encore pleinement apprécié ou compris et qu’un contrôle social a de tout temps limité l’accès au parc [11], un constat appuyé par Beardsley à travers la notion «d’érosion[12]». Cette lecture demeure plus que jamais valable et comprise dans la planification et la conception. Les aménagements proposent ainsi à la fois des opportunités de rencontres, de contact social et de rapprochement avec la nature, une complémentarité entre les espaces verts et urbains, une variété d’espaces et de types de paysages ouverts et fermés qui permet des activités dynamiques et statiques, récréatives et passives. À l’instar des écrits de Jean-Marc Besse[13], le plan d’aménagement considère le paysage avant tout comme une expérience, une manière d’être, d’y être impliqué pratiquement, c’est-à-dire de l’habiter. Les propositions visent moins à contempler qu’à vivre et sentir le paysage. La promenade riveraine de 15 km permettant de découvrir les paysages des rives des deux îles ainsi que les panoramas sur le fleuve Saint-Laurent et même au-delà est le premier geste d’aménagement clé pour renforcer l’identité du Parc et en faire une destination. Cela permet de réhabiliter la passerelle du Cosmos et le pont de l’Expo-Express et d’offrir un contact direct avec l’eau tout en bonifiant l’intérêt écologique du pourtour des îles.

Une matrice verte comme structure de connectivité

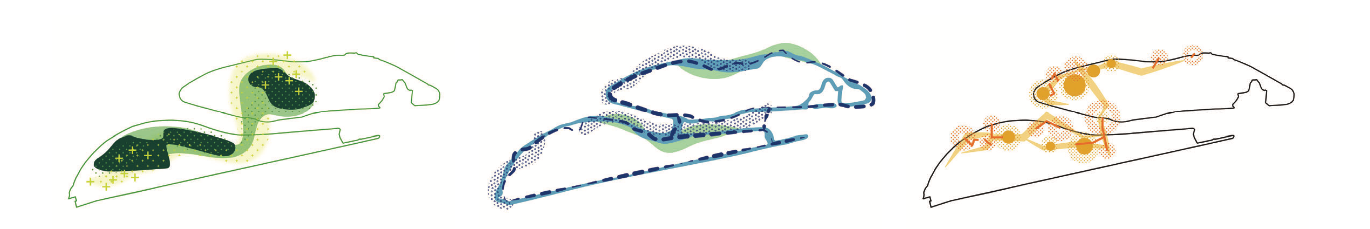

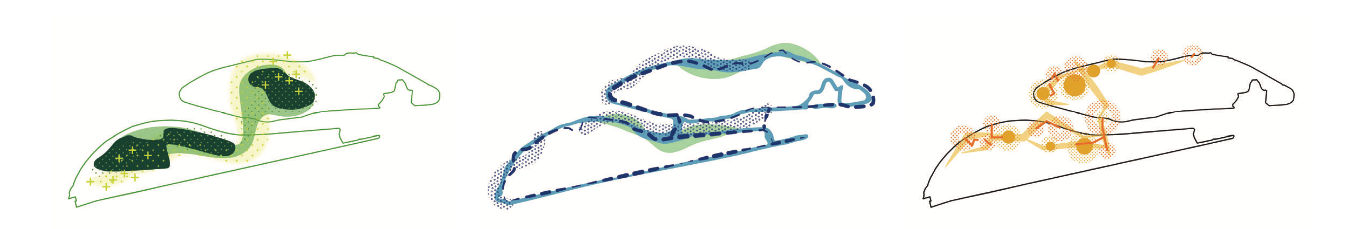

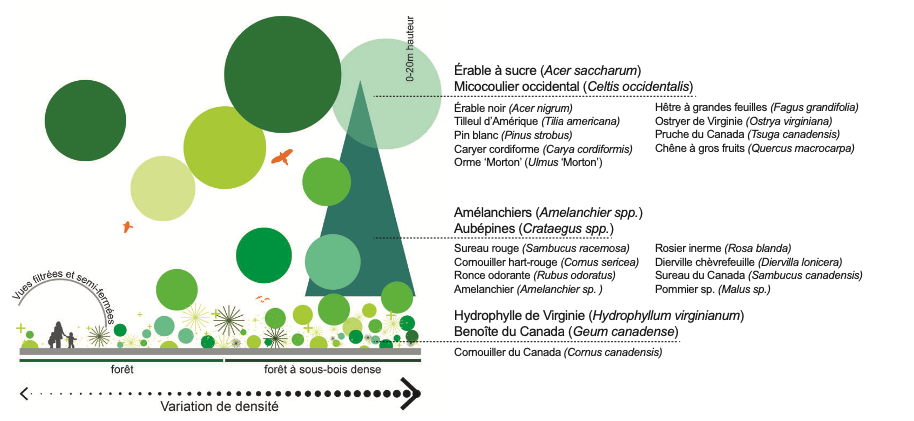

En s’inspirant de la triade Bridging, Mediating, Reconciling d’Elizabeth Meyer[14], la stratégie d’aménagement voulait reconnecter les espaces, faire une médiation des vocations et se réconcilier avec le lieu. Influencée par l’approche «Process-based» d’Anita Berrizbeita[15], la conception s’est appuyée sur les formes existantes, le sens du lieu et l’accumulation des histoires pour révéler la trajectoire du Parc, augmenter la lisibilité des forces et faire émerger une matrice qui répond à la multiplicité, la flexibilité et la temporalité nécessaires à la vie d’un grand parc urbain. Aux qualités visuelles et spatiales recherchées s’ajoutent des notions de préservation, de performance, de connectivité et de fonctions écologiques. Gilles Clément posait la question : «Peut-on élever le non-aménagement, et parfois le désaménagement, à hauteur de projet?[16]» Sans aller jusqu’à proposer une pédagogie de l’herbe, le plan d’aménagement laisse une grande place à la protection des paysages aménagés et naturels et au design écologique adaptatif, en plantant massivement et en restreignant l’accès à plusieurs secteurs du parc. La liaison des cœurs des deux îles est le deuxième geste d’aménagement clé à travers la création d’un corridor écologique entre la micocoulaie du mont Boullé et les zones ripariennes de l’île Notre-Dame via un pont vert au-dessus du chenal Le Moyne. Cela permet d’assurer une connectivité des écosystèmes au sein du Parc et d’enrichir ces noyaux de biodiversité, où la faune et la flore sont particulièrement abondantes[17].

Un paysage hérité stratifié

Bernard Huet disait qu’un parc avait une continuité, une longue histoire[18], alors que Peter Latz affirmait qu’un parc n’était jamais complété, mais devait plutôt être considéré comme un processus continuel[19]. Cette vision d’agrégation qui a émergé dans les années 1990 se matérialise notamment dans les approches et les projets d’Adrian Geuze et de Norfried Pohl qui misaient sur les qualités intrinsèques du lieu comme inspiration conceptuelle. «This is one of the reasons why it is necessary to add different layers over a period of time in order to evolve into a ’public park of stature’; ‘because the already existing and intented qualities must be understood and not forgotten’ [20]». En tant que paysage patrimonial ayant eu plusieurs phases de planification et couches d’occupation, il est apparu fondamental de tirer profit de la fragmentation du parc Jean-Drapeau plutôt que d’y voir qu’amalgame de choses disparates qu’il convient de lisser. L’idée n’était pas de créer un nouveau grand geste monumental, mais de faire état que le parc est un produit évolutif depuis plusieurs siècles. La prise en compte des traces, la révélation des couches et la superposition de trames ont été les bases de la réflexion. Les objectifs étaient d’inviter le public à se réapproprier le parc, de le réinscrire dans la mémoire collective et d’assurer une continuité tout en ajoutant une nouvelle structure et organisation spatiale. Le plan d’aménagement propose ainsi une matrice pour rendre manifeste l’existant et conjuguer différentes «associations de temps»[21].

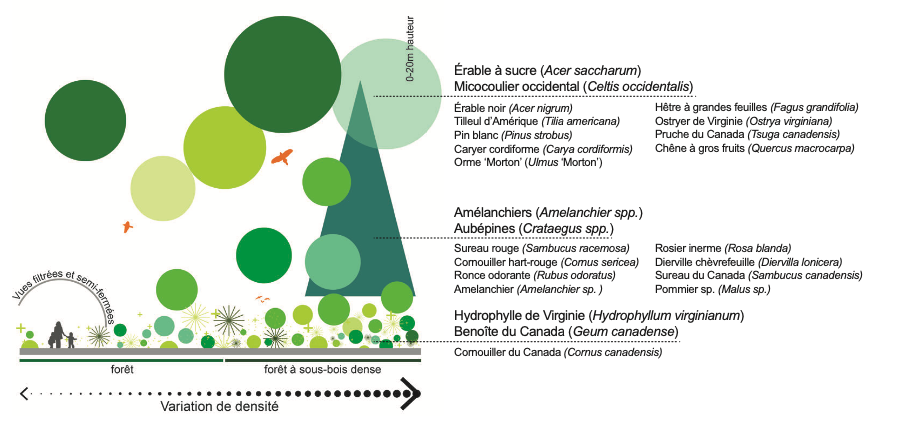

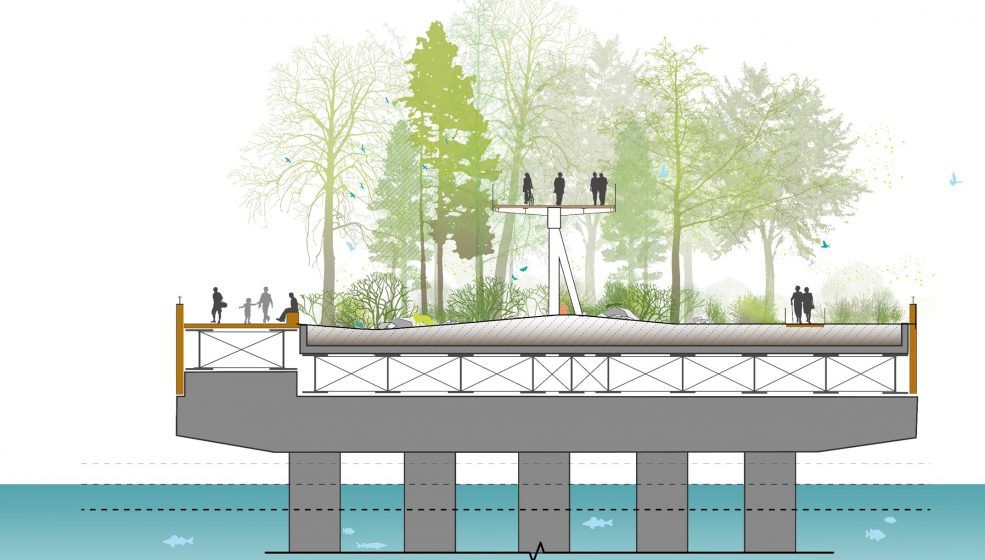

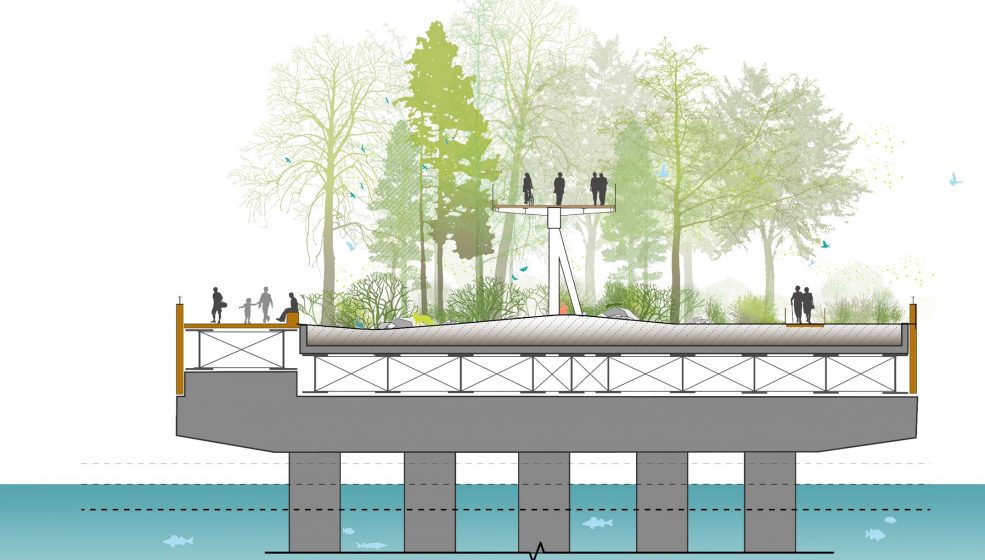

Dans la considération de la valeur patrimoniale du Parc et dans la logique de la «conservation inventive» de Pierre Donadieu[22], l’aménagement de l’espace a privilégié à la fois la conservation d’éléments concrets du paysage et la création de formes innovantes correspondant à de nouvelles ou à d’anciennes fonctions du territoire. Le concept d’aménagement s’est attardé à enrichir la tridimensionnalité du paysage, ce que Jacques Simon nommait des «rapports d’alliances et d’autonomies de trois étages distincts de l’organisation de l’espace[23]». C’est dans ce contexte que le troisième geste d’aménagement clé a été imaginé, celui des attaches entre les rives et les cœurs. Ce geste est intimement lié à l’expérience de la promenade riveraine ainsi qu’à celle des cœurs historiques et écologiques du Parc. Les attaches comprennent une déclinaison d’objets paysagers (passerelles, quais, belvédères) qui permettent de décloisonner et de relier les paysages enclavés tout en offrant une expérience unique «à plusieurs niveaux» qui révèle et expose l’identité du Parc. Cette série de liens ponctuels et continus répartis sur les deux îles offre un nouveau regard sur des trésors oubliés et sur les paysages du fleuve tout en créant de nouveaux dialogues entre les ensembles autrefois isolés. Les passerelles sont inspirées des structures aériennes du minirail de l’Expo 67, à l’époque constituées de pilotis en forme de V inversé reliés par une longue poutre longitudinale. Leur matérialité dialoguera avec la signature contemporaine du paddock et des futurs bâtiments de parc, contribuant ainsi à l’émergence d’une identité architecturale ancrée dans l’histoire et l’imaginaire du lieu.

Le ménagement d’un «parc public d’envergure»

Certes, de grands projets transformeront l’image, la mobilité et l’expérience du parc Jean-Drapeau, mais ils le seront principalement sur des terrains sous-exploités et des infrastructures existantes n’incarnant pas les valeurs du Parc. Nous ne sommes plus à l’heure de l’invention d’un nouveau paysage, mais à celle de prendre soin de notre territoire, de le lire, de le repenser et de le valoriser. Comme l’exprimait si bien Thierry Paquot : «Il faut inventer un ménagement des gens, des lieux et des choses[24]». Le parc Jean-Drapeau n’est pas et ne sera pas une esthétique unifiée et finale, mais un amalgame cohérent de formes héritées qui s’adapteront à de nouvelles préoccupations environnementales et pratiques sociales. C’est là que résidera l’innovation et que se concrétisera l’identité retrouvée et rehaussée du parc Jean-Drapeau. C’est en privilégiant les superpositions, les connexions et les médiations qu’aura lieu la réémergence d’un grand parc urbain aspirant à devenir un «parc public d’envergure».

Jonathan Cha

Montréal

Références

[1] Cet article est une version plus détaillée de l’article : Jonathan Cha (2022), « Superpositions, connexions et méditations, la réémergence d’un grand parc urbain », p. 35-37, Paysages, no-17.

[2] James Corner (1991), « Theory in Crisis » in Simon Swaffield, Theory in Landscape Architecture, Philadelphie, University of Pennsylania Press, p. 20-21.

[3] Alexander Garvin (2011), « Park development », in Public Parks. The key to livable communities, New York et Londres, W. W. Norton & Company, p. 58.

[4] Bernard Huet (1995) [1993] « Park design and continuity », in Martin Knuijt, Hans Ophuis, Peter van Saane et David Louwerse, Modern Park Design. Recent Trends, Bussum, Thoth Publishers, p. 21.

[5] Kate Orff (2016), « Urban Ecology as activism », in Landscape Architectural Foundation, New Landscape Declaration, Los Angeles, Rare Bird Booksp, p. 77-79.

[6] Clare Cooper Marcus et Carolyn Francis (1990), People Places. Design guidelines for Urban Open Space, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, p. 71.

[7] William H. Whyte (1980), The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces, Washington, The Conservation Foundation, 125 p.

[8] Clare Cooper Marcus et Carolyn Francis (1990), People Places. Design Guidelines for Urban Open Space, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 295 p.

[9] Alan Tate et Marcella Eaton (2015), Great City Parks, New York, Routledge, 332 p.

[10] Halil Özgüner (2011), “Cultural Differences in Attitudes towards Urban Parks and Green Spaces”, Landscape Research, Vol. 36, no-5, p. 599-620.

[11] Galen Cranz (1982), The Politics of Public Parks. A History of Urban Parks in America, Cambridge, The MIT Press, 347 p.

[12] John Beardsley (2007), « Conflict and Erosion : The Contemporary Public Life of Large Parks » in Julia Czerniak et James Corner, Large Parks, New York, Princeton Architectural Press, p. 199-213.

[13] Jean-Marc Besse (200), “Le paysage et les discours contemporains: Prolégomènes” in J.-B. Brisson (dir.), Le jardinier, l’artiste et l’ingénieur, Paris, Les Éditions de l’Imprimeur, p. 71-89.

[14] Elizabeth Meyer, « Uncertain Parks : Disturbed Sites, Citizens, and Risk Society”, in Czerniak et Hargreaves, op.cit. : 59-85.

[15] Anita Berrizbeitia, « Re-placing Process » in Czerniak et Hargreaves, op.cit. : 175-197.

[16] Gilles Clément (2006), Où est l’herbe?, Arles, Actes Sud, 159 p.

[17] Pour plus de détails, voir Jonathan Cha (2021), « La réinvention du parc Jean-Drapeau : un nouveau parc plus accessible, diversifié, public, et vert » , The Nature of Cities, 18 octobre : https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2021/10/18/la-reinvention-du-parc-jean-drapeau-un-nouveau-parc-plus-accessible-diversifie-public-et-vert/.

[18] Knuijt, Ophuis, van Saane et Louwerse (1995) [1993], « Time, space and landscape », op.cit. : 83.

[19] Knuijt, Ophuis, van Saane et Louwerse (1995) [1993], « A park est un parc is een park ist ein Park », op.cit : 30.

[20] Knuijt, Ophuis, van Saane et Louwerse (1995) [1993], « Continous change or changing continuity », op.cit. : 34.

[21] Knuijt, Ophuis, van Saane et Louwerse (1995) [1993], « Time, space and landscape », op.cit. : 84.

[22] Pierre Donadieu (1994), « Pour une conservation inventive des paysages » in Augustin Berque et al, Cinq proposition pour une théorie du paysage, Paris, Éditions Champ Vallon, p. 52-81.

[23] Des surfaces (0 à 2 mètres) à l’organisation topographique et végétale (2 à 8 mètres) jusqu’au massif forestier (8 à 20 mètres) Jacques Simon (1980), Les parcs actuels, (Ser. Aménagement des espaces extérieurs, no-13). Espaces ouverts, 127 p.

[24] « Thierry Paquot, « Il faut inventer un ménagement des gens, des lieux et des choses ». Entrevue avec Thierry Paquot, Philosophie magazine, 19 mars 2014.

* * *

The Conceptual Approach of the Parc Jean-Drapeau Conservation, Planning, and Development Master Plan 2020-2030

As a heritage landscape with many years of history, it seemed fundamental to incorporate the fragmentation of Parc Jean-Drapeau rather than trying to smooth it out. The idea was to acknowledge that the park is an evolving product of several centuries, recovering lost meaning and affirming identity.

Today’s parks are an eclectic collection of layers of landscapes built and developed from multiple eras. For both park makers and park designers, it is appropriate to question the balance between revealing and celebrating the historicity of parks and their components and applying updated approaches to transformation to make them responsive to the needs of the 21st century. How can we consider the heritage they contain and represent while leaving room for the production of new contemporary forms? Is a cohabitation of functions, styles, and traces possible and desirable? How can we respond to the elements of rupture and obsolescence while ensuring a continuity of identity for the site? What forms should the parks of the future take?

These questions informed the conceptual approach of the Master Plan for the Conservation, Planning, and Development of Parc Jean-Drapeau 2020-2030, produced and directed by NIPpaysage, with Réal Paul, architects, ATOMIC3, and Biodiversité conseil.

In recent decades, the public use of Jean Drapeau Park has been in crisis. A distancing and estrangement from citizens have occurred to the point of making the park a “landscape of estrangement” to use James Corner’s concept. Corner criticized technology and capitalism for distancing us from the poetic value of landscape architecture and advocated a reconciliation of the history and meaning of place with contemporary circumstances. “Many fail to even appreciate the role that landscape architecture plays in the constitution and embodiment of culture, forgetful of the designed landscape’s symbolic and revelatory powers, especially with regard to collective memory, cultural orientation, and continuity. It was, therefore, necessary, through the landscape design process, to clearly position the Park’s identity in order to give it physical coherence, reflect its cultural values, and reintegrate it into the practices of citizens. After identifying conservation as one of the main strategic orientations, seven planning principles were developed: positioning the Park on a metropolitan and regional scale, celebrating the Park’s island character, highlighting its rich heritage, emphasizing the aquatic landscapes and their ecosystems, promoting ecosystem diversity and connectivity, ensuring a continuum of landscape experiences in the Park, and focusing on mobility experiences as a means of exploring the Park. The concept of development that directly responds to this loss of meaning and contact is: “The celebration of the great island park through the consolidation of its shores and the heart of St. Helen’s and Notre Dame Islands.

The park and landscape as a landscape and social destination

In the manner of Frederick Law Olmsted’s parks, the shared desire was to make the reinvented island landscape of Jean Drapeau Park a destination in itself. Examples include Central Park, Millennium Park, and Governor’s Island, where the quality of the design was intended from the planning stage to be a major local and tourist attraction. The development plan for Parc Jean-Drapeau also aims to create emptiness, to let the Park’s design express itself in all its creativity. As Bernard Huet pointed out: “We are afraid of emptiness. Afraid of void, of an empty, beautiful space. The importance of not overloading and filling the space with temporary installations of all kinds (signs, barriers, fences, furniture, floral arrangements, platforms, etc.) as well as aiming to optimize the landscapes has been a major part of the reflections to enhance the heritage site, celebrate the legacies of landscape architecture and especially contribute to the emergence of inhabited environments. As Kate Orff wrote in The New Landscape Declaration: “Where the spaces can be reimagined as productive landscapes that are not only pastoral settings but also active generators of social life.

Clare Cooper Marcus wrote that: “Two frequently cited reasons for park use are: a desire to be in a natural setting and a need for human contact”, an observation that is still valid today and that informed the entire creative process. This process was also based on the “guidelines”, “design recommendations” and “users’ needs” developed by several authors over the years, including Jan Gehl’s quality criteria for spaces frequented by pedestrians (2012), which highlighted the elements that make public spaces successful (notably Whyte, 1980, Cooper Marcus and Francis, 1990, Tate and Eaton, 2015). The thinking has been particularly concerned with meeting the needs and habits of all users and cultural communities through a commitment to diversity. Various authors have indeed studied cultural differences in attitudes, behaviors, and occupations of parks; some cultural groups prefer more meal gatherings or passive recreation, and others prefer movement and active recreation as examples.

These insights from scientific research and field observations have been seriously considered to ensure social justice in park accessibility (equality, equity, inclusion). In The Politics of Parks Design, Cranz wrote that the potential of parks to shape and reflect social values is not yet fully appreciated or understood and that social control has historically limited access to the park, a statement supported by Beardsley through the notion of “erosion. This reading remains more valid and understood than ever in planning and design. The developments thus offer opportunities for encounters, social contact and closeness to nature, a complementarity between green and urban spaces, a variety of spaces, and types of open and closed landscapes that allow dynamic and static, recreational, and passive activities. Following the example of Jean-Marc Besse’s writings, the development plan considers the landscape above all as an experience, a way of being, of being practically involved in it, that is to say, of inhabiting it. The proposals aim less at contemplating than at living and feeling the landscape. The 15-km shoreline promenade, which will allow visitors to discover the landscapes along the shores of the two islands, as well as the panoramic views of the St. Lawrence River and beyond, is the first key development to reinforce the Park’s identity and make it a destination. This will allow for the rehabilitation of the Cosmos footbridge and the Expo-Express bridge, providing direct contact with the water while enhancing the ecological interest of the islands’ perimeter.

A green matrix as a connectivity structure

Inspired by Elizabeth Meyer’s Bridging, Mediating, Reconciling triad, the planning strategy sought to reconnect spaces, mediate vocations, and reconcile with place. Influenced by Anita Berrizbeita’s process-based approach, the design drew on existing forms, sense of place, and accumulated histories to reveal the trajectory of the park, increase the legibility of strengths, and emerge a matrix that responds to the multiplicity, flexibility, and temporality necessary for the life of a large urban park. In addition to the visual and spatial qualities sought, there are notions of preservation, performance, connectivity, and ecological functions. Gilles Clément asked the question: “Can we raise the non-development, and sometimes the disdevelopment, to the level of a project? “Without going so far as to propose a pedagogy of grass, the development plan leaves a lot of room for the protection of developed and natural landscapes and for adaptive ecological design, by planting massively and restricting access to several areas of the park. Linking the hearts of the two islands is the second key design gesture through the creation of an ecological corridor between the Mount Boullé wetland and the riparian areas of Ile Notre-Dame via a green bridge over the Le Moyne Channel. This will ensure the connectivity of the Park’s ecosystems and enrich these biodiversity nodes, where flora and fauna are particularly abundant.

A stratified inherited landscape

Bernard Huet said that a park has a continuity, a long history, while Peter Latz said that a park is never completed, but rather should be seen as a continuous process. This vision of aggregation, which emerged in the 1990s, is reflected in the approaches and projects of Adrian Geuze and Norfried Pohl, who relied on the intrinsic qualities of place as conceptual inspiration. “This is one of the reasons why it is necessary to add different layers over a period of time in order to evolve into a ‘public park of stature’; ‘because the already existing and intended qualities must be understood and not forgotten’.

As a heritage landscape that has had several planning phases and layers of occupation, it seemed fundamental to take advantage of the fragmentation of Parc Jean-Drapeau rather than seeing it as an amalgam of disparate things that should be smoothed out. The idea was not to create a new great monumental gesture but to state that the park is an evolving product for several centuries. Taking into account of traces, the revelation of layers and the superposition of frames were the bases of the reflection. The objectives were to invite the public to reappropriate the park, to reinscribe it in the collective memory, and to ensure a continuity while adding a new structure and spatial organization. The development plan thus proposes a matrix to make the existing manifest and to conjugate different “associations of time”.

In consideration of the Park’s heritage value and in the logic of Pierre Donadieu’s “inventive conservation”, the planning of the space has privileged both the conservation of concrete elements of the landscape and the creation of innovative forms corresponding to new or old functions of the territory. The concept of planning has focused on enriching the three-dimensionality of the landscape, what Jacques Simon called “relationships of alliances and autonomies of three distinct floors of the organization of space. It is in this context that the third key planning gesture was imagined, that of the ties between the banks and the hearts. This gesture is intimately linked to the experience of the riverside promenade as well as to that of the Park’s historic and ecological hearts. The links include a series of landscape objects (footbridges, quays, belvederes) that break down the barriers and connect the enclosed landscapes while offering a unique “multi-level” experience that reveals and exposes the Park’s identity. This series of punctuated and continuous links across the two islands offers a new look at forgotten treasures and river landscapes while creating new dialogues between once-isolated ensembles. The footbridges are inspired by the aerial structures of the Expo 67 minirail, which at the time consisted of inverted V-shaped pilings connected by a long longitudinal beam. Their materiality will dialogue with the contemporary signature of the paddock and future park buildings, contributing to the emergence of an architectural identity rooted in the history and imagination of the site.

The creation of a “major public park”

It is true that major projects will transform the image, mobility, and experience of Jean Drapeau Park, but they will be carried out mainly on underused land and existing infrastructures that do not embody the values of the Park. We are no longer at the time of the invention of a new landscape, but at the one to take care of our territory, to read it, to rethink it, and to develop it. As Thierry Paquot expressed it so well: “We must invent a way of caring for people, places and things”. Jean Drapeau Park is not and will not be a unified and final aesthetic, but a coherent amalgam of inherited forms that will adapt to new environmental concerns and social practices. This is where innovation will reside and where the new and enhanced identity of Parc Jean-Drapeau will take shape. It is by privileging superimpositions, connections, and mediations that the re-emergence of a large urban park aspiring to become a “major public park” will take place.

Jonathan Cha

Montreal

See Notes and References at the end of the French version above.

Leave a Reply