“This is a crucial and much-neglected topic. If children are not designed into our cities, they are designed out. This means that they are deprived of contact with the material world, with nature, with civic life and with their own capacities.” George Monbiot (Arup, 2020, 15)

How can Liverpool City Council more meaningfully shape a better world? By creating a city that offers streets, spaces, and facilities for all ages, abilities, and backgrounds to enjoy together. A child-friendly approach has the potential to unite a range of progressive agendas and to act as a catalyst for urban innovation. But it hasn’t been easy.

1 Where do children belong in a city?

Globally there are countless examples of city-wide projects that endorse child-friendly cities, such as the Belfast Healthy Cities partnership, Climate Shelters in Barcelona, the Oasis project in Paris, and a mobility app in Oslo. Yet, providing multi-functional, playable space in nature for children ― beyond the playground ― seems to have largely been written out of urban planning agendas. The aim of this paper is to draw attention to the incoherence between local government support for child-centred and green planning and their unprecedented neoliberalisation-linked budget cuts and residential property development.

The case study of a community-led urban park in Liverpool called the Baltic Green serves as a strong example of how local councils are prioritising financial projections and urban development over the needs of cities’ children. Overall, this paper contributes to wider discussions around children’s access and exposure to (urban) nature. The literature review, case study, and discussion build up a cohesive argument to emphasise that we must prioritise children’s outdoor play in urban planning. It is clear that putting children centre-stage in city planning can help make a city safe, inclusive, and accessible.

2 Methodology

I observed a combination of qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis. A literature review was executed by synthesising academic articles, journals, reports, and books using a keyword search[i]. I also carried out one semi-structured interview with the brainchild of the Baltic Green project, Tristan Brady-Jacobs (See Appendix B for interview questions). In the interest of full disclosure, I sporadically volunteered at the Baltic Green between February 2021 and June 2021. Therefore, I am in a unique position to recall the evolution of the park and access an abundance of primary data.

3 Literature Review

Child-friendly urban planning is an emerging field to increase efforts in improving children’s development, health, and access to opportunities. Such endeavours have been

neglected over economic, spatial, and welfare developments in the context of neoliberal urbanisation. Cities have become increasingly motorised and hostile with few outdoor places reserved for children. The context of austerity, disinvestment in the public realm, and the dismantlement of social and welfare structures led to the emergence of new spaces and activities for children, such as commercial indoor playtime activities and organised after-school activities (Karsten, 2005). Clearly, children’s access to and participation in non-commodified urban spaces and their associated health, equality, and well-being concerns have been limited (Karsten 2005). The literature presented in the following section will make a compelling case for the importance of providing access to nature in the places where children live, play, and learn.

There is an abundance of research showcasing the detrimental effects of Nature Deficit Disorder amongst children living a suburban, sedentary, and indoor lifestyle (Baró, 2021, 2). This condition encapsulates the loss of children’s free-ranging exploration of ‘‘wild lands’’ in cities and suburbs, as children’s attention is absorbed by televisions and computer screens, parents’ fears for children’s safety outdoors grew, and bulldozers relentlessly removed wild edges (Chawal, 2015, 434). Karsten divided the experiences of children into the self-explanatory categories of “inside children” and “outside children”, drawing attention to the present-day rarity of the latter (2016, 76). Multi-sensory, experiential outdoor learning amongst flora and fauna has been shown to benefit children socially, psychologically, academically, and physically, fostering a sense of shared responsibility and cooperation. In these uncertain times of environmental destruction, Oscilowicz postulates that children show greater environmental stewardship and attachment to nature through regular engagement with nature (2020, 778). It is vital to instill children with such values in order to imagine a future in which the human megatropolis can live in harmony with nature, something to be chartered by the young people of today.

More generally, environmental justice literature has shown that green play spaces are critical assets that may improve community presence, cohesion, and resilience (Oscilowicz, 2020, 782). In Arup’s report ‘Cities Alive: Designing for Urban Childhoods’, they emphasised that spaces that are free at the point of access and provide a mix of uses, natural elements, and activities away from congestion are a powerful tool to decrease inequality between different communities (2017, 37). The report elaborates on how green amenities can facilitate social cohesion and community building or in other words “an inclusive space that opens the door to interaction” (Arup, 2017, 27). Oscilowicz further defends this theory by stating that urban parks, gardens, and community gardens provide neighbours with an opportunity to build community by facilitating chance encounters (767, 2020). This point illustrates how green spaces are beneficial for a multitude of stakeholders, a priority being the developmental benefits to the children, but also social connections for the guardian, parents, grandparents, and caretakers (Oscilowicz, 2020, 768). Intergenerational interactions, serendipitous encounters, and multicultural exchange are invaluable consequences of open green spaces for children.

Such spaces played a crucial role during the COVID-19 lockdown. Many countries imposed strict rules on people’s movement and interaction to limit the spread of the virus, thus city dwellers found solace and joy in their local green space. Outdoor sites became popular and overcrowded, demonstrating the very value of open spaces in cities, and thereby postulating the importance of their maintenance and funding. Now more than ever, community planners and city officials should consider prioritising the cultivation of high-quality play spaces with public infrastructure and programming.

A number of authors have recognised the importance of ‘everyday freedoms’ for children (Chawal 2015, Baró 2021). This idea combines the ability of children to play and socialise with high levels of independent mobility, establish supportive social groups and multicultural relationships, and strengthen their overall emotional and relational well-being (Baró, 2021, 2). As enshrined in the UN Convention on the Rights of a Child “play is an instinctive, voluntary, and spontaneous human learning impulse, and a basic human right. Nussbaum supported this argument by listing affiliation as one of the central capabilities to compose human well-being; being able to live with and toward other people, engage in various forms of social interaction, imagine the situation of another and show concern for others (2013, 444). She views creative play as a starting point for children to exercise these capabilities. Furthermore, in Chawla’s research, they also adopt a philosophical lens to underpin the importance of health and well-being. They revive Aristotle’s notion of eudaimonia or happiness, often translated as ‘‘human flourishing’’, as the ultimate goal of human life, achieved through people’s full and balanced realisation of their capabilities (Chawal, 434, 2015). Another author argues that neighbourhood green play spaces may be the only space where children experience-free exploration and liberty in an urban setting (Oscilowski, 768, 2020). In light of these discussions, the importance of play environments for children is clear to enable them to explore, test their capabilities, contribute to their social and cognitive development, acquire new knowledge and skills, and enjoy a sense of competence (Chawal, 438, 2015).

One leading academic within the topic of children’s access to nature is Roger Hart, he completed his dissertation on Children’s Experience of Place in 1979. His later work tracked how his ability to carry out research on children’s interaction with nature became increasingly difficult from the 1970s to the early 2000s. He attributes this to the new culture of fear among parents, who over the years have relinquished children’s right to roam. This parental control and protection are evident within a multitude of comparative studies, for example, children in countries such as Finland and Germany are granted high levels of independent mobility (Arup, 2017, 16; Karsten, 2016, 77). These findings serve as a reminder of how children in the UK who walk (or less frequently bike) independently to school or other hobbies have now become the exception (Karsten, 2016, 77).

There exists a considerable body of literature on the positive associations between urban nature and child well-being including benefits to mental and physical well-being. Interaction with nature has been demonstrated to have a positive impact on both physical and mental health, this can include ADD/ADHD, overall mental health, stress, resilience, self-esteem, depression, respiratory diseases and allergies, neonatal survival, and mitigating pesticide risks (Tillmann, 2018, 958; Chawal 2015). Chawla draws on a series of reports to substantiate her research claims of the benefits of green spaces on children’s health. For example, when Scottish families with young children live less than twenty minutes walking distance from a green space, mothers rated the general health of their children as higher (Aggio et al. 2015 in Chawal, 434, 2015). Furthermore, Dutch children who lived near green spaces had lower rates of respiratory diseases (Maas et al. 2009), and four- and five-year-olds in the United States who lived in neighbourhoods with more street trees were less likely to have asthma (Lovasi et al. 2008).

Given all the literature outlined above, this section has built up a clear overview of why cities ought to pay attention to facilitating access and exposure to urban nature for all residents. There is an abundance of research advocating for the benefits of access to urban green spaces, this underpins the calls of families for clean, safe, and green neighbourhoods.

4 Case Study of the Baltic Green

Liverpool proclaims itself as the gateway to nature given the ability to access a wide variety of natural landscapes including greenery, forestry, seaside, and coastal regions. The city council manages over 500 parks in the region (Open Spaces, 2022). Yet, despite attention to community cohesion and social interaction highlighted in local planning documents, it seems the local authority’s focus on children has ceased to be compulsory. The context of austerity and dismantlement of social and welfare structures has been further compounded by the abolition of the National Play Strategy. Youth services in England and Wales have been cut by 70%, with the loss of £1bn of investment resulting in zero funding in some areas (Weale, 2020). The following section will illustrate how, despite attempts by local community groups, access to urban nature for children in Liverpool has been interrupted.

Historically a place of industry, the Baltic Triangle is now considered one of Liverpool’s most bohemian areas and has emerged as a popular cultural hotspot, as well as a place to live surrounded by thriving creative and digital industries. The area is indistinguishably marked by the plethora of coffee shops, bars, convenience stores, yoga studios, co-working spaces, and new residential property developments. In and amongst this symbiotic mix of businesses, residences, and amenities, there is a single remaining patch of green.

The plot of land was described by Liverpool City Council in the Strategic Regeneration Framework as “poorly maintained and requires improvement” (2020, 15). In February 2021, during the second wave of the COVID-19 lockdown, a team of volunteers assembled to transform the site into a multi-purpose recreational space. By all means, an upgrade from the previously abandoned and uninviting scenery. It was born from the desire to install tables and chairs for local residents to utilise on their daily outings permitted during the COVID-19 lockdown. This idea evolved to see volunteers and artists build a variety of structures, this included a puppet stage, a chess board, large thrones, and a wooden dragon.

Complimentary to the wooden creations, volunteers planted trees to border the park, treated the grass, and put in waste management facilities. The site rapidly became a popular meeting spot for residents, families, and construction workers or a welcome discovery for people walking past. The green provided a space for young and old to meet, sparking exchange, interaction, and delight.

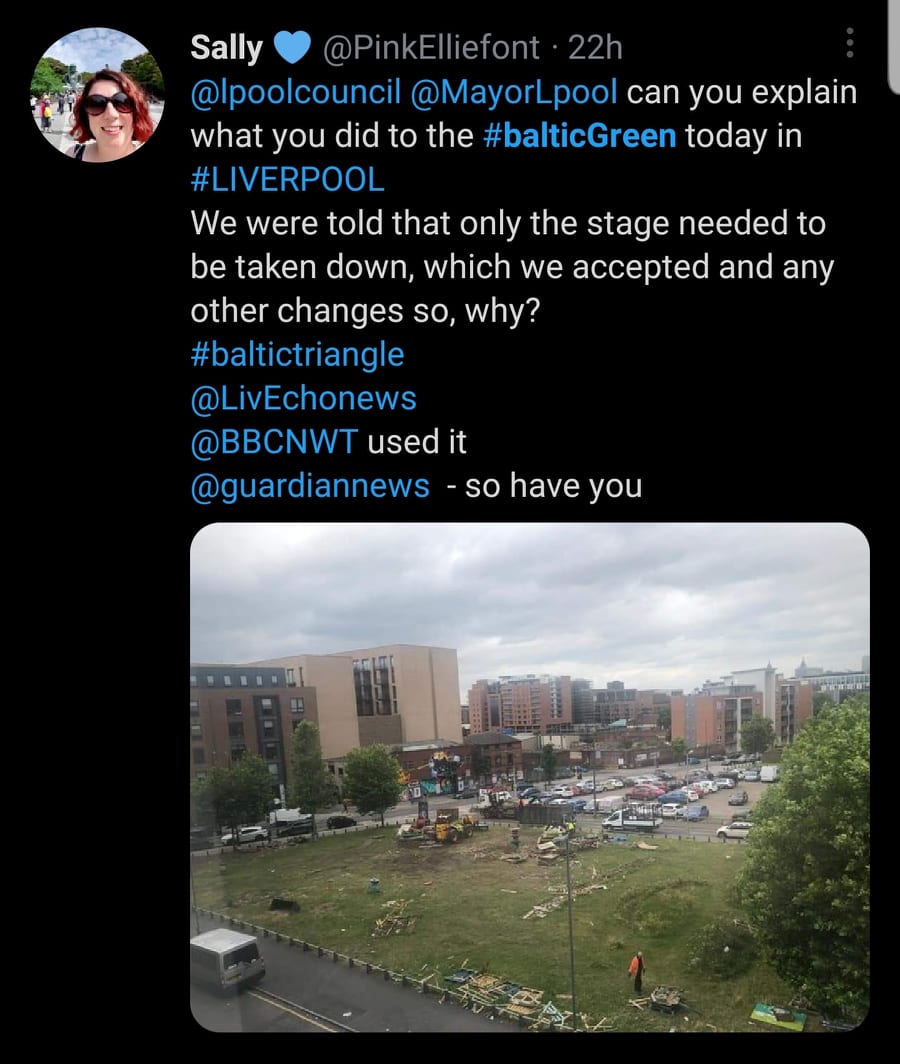

Efforts were pursued by the team of volunteers to obtain permission from the council to establish the site as a permanent urban park. Such status would require financial support, health and safety assessment, and insurance. Despite the success of the park, the values collided with Liverpool City Council. The council pursued a litany of complaints and faults with the project, its intentions, and provisions for the area. First, the council representatives issued complaints about anti-social behaviour being attracted to the site at night time, such as excessive noise, street drinking, and recreational drug use. But when pest control discovered rats on the site, the council heeded this problem and ordered the removal of three structures. The council’s instructions were responded to by the volunteers. Diligently, they removed the “rodent-infested” structures, continued to clear garbage bins, and maintained clear communication with the council about their actions. Nonetheless, the Baltic Green was bulldozed in the early hours of the 7th of June 2021 by Liverpool City Council.

Today, the site has reverted to its previous desolation visited only by the occasional dog walker or resident crossing it en route elsewhere. It is hard to imagine that this plot once hosted the creations of volunteers and artists. The Baltic Triangle has already been subject to worrying tell-tale signs of gentrification whereby the financial projections of developers have been prioritised over the local needs of residents. It is clear there are tensions arising between the longstanding businesses, the new inhabitants, and the agenda of the local council, and the Baltic Green is the epicentre of this collision.

5 Discussion

Equipped with a detailed understanding of the urban, environmental, and socio-economic context of the Baltic Green from previous sections, this part of the paper will extrapolate the ways in which the site fulfilled children’s access and exposure to outdoor spaces and in turn aided the prosperity of the local community. The discussion will not attempt to rebut the decisions made by Liverpool City Council but instead illuminate the tragic loss of a unique community-led initiative to meet the demands of a neoliberal city.

In the literature review, numerous studies emphasised the importance of independent and creative play for children in nature. The Baltic Green offered a unique and experimental way for children to interact with space. The fencing, constructed by volunteers, reduced the need for constant parental supervision. As the structures did not match the standardised and monotonous amenities found in a children’s play park, the wooden creations provoked children to use their imagination to interact and play with the unfamiliar objects. This approach recognised the fundamental importance of independent play and learning to help shape a child’s development and prospects, hence their adult lives. When interviewing Tristan, he encapsulated this idea by saying “if we control the way they [children] think, we control their development and we don’t get new ideas or concepts.” Furthermore, Tristan recalled the “wonderful feedback” from parents and guardians’ thoughts on the space given its unique offering.

As revealed in the map in Appendix A, the Baltic Green is one of the few remaining green spaces within the urban density of the Liverpool City Centre. In the Strategic Regeneration Framework (SRF), it reports that there are now in excess of 14,000 residential units in total in the city centre core with a resident population of 45,000. In addition, there is a potential 12,800 units in the proposed pipeline across 31 schemes (Liverpool City Council, 2020, 8). Such developments are displacing children and families to other (indoor) play spaces or increasing the likelihood of them staying home. Although Liverpool boasts a wide variety of family activities, such as museums, restaurants, and festivals, such events include parental supervision as an integral part of the experience. Where do children have the space to engage in outdoor, autonomous, and non-commodified play? The Baltic Green was one of the few remaining outdoor provisions in the area that offered a versatile function for all generations. The destruction of such spaces promotes sedentary and indoor lifestyles and as discussed in the literature review this has negative impacts on a child’s health, well-being, and cognitive development.

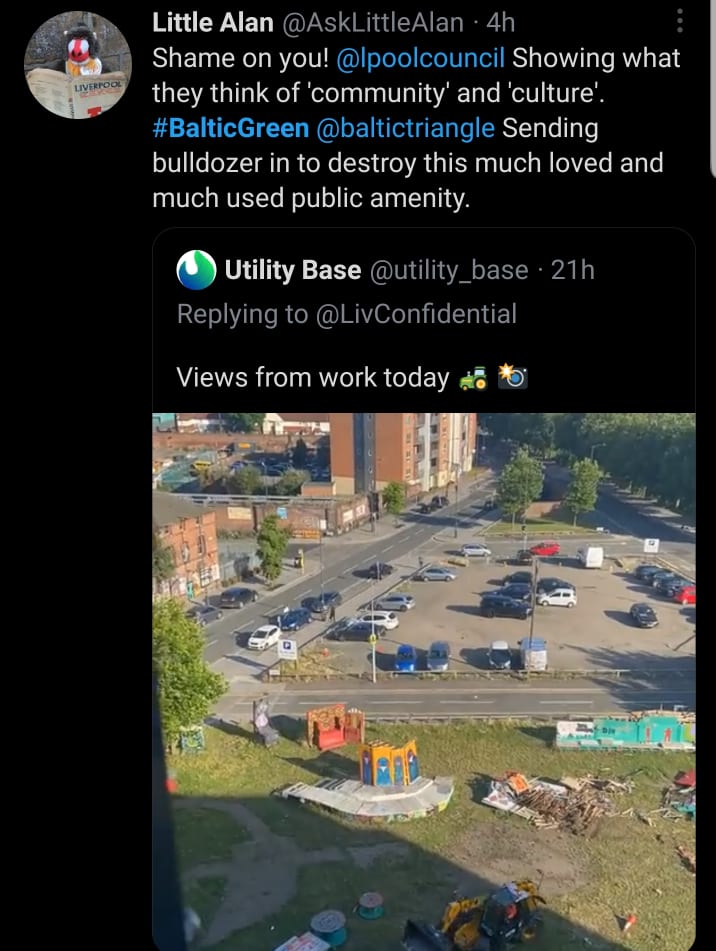

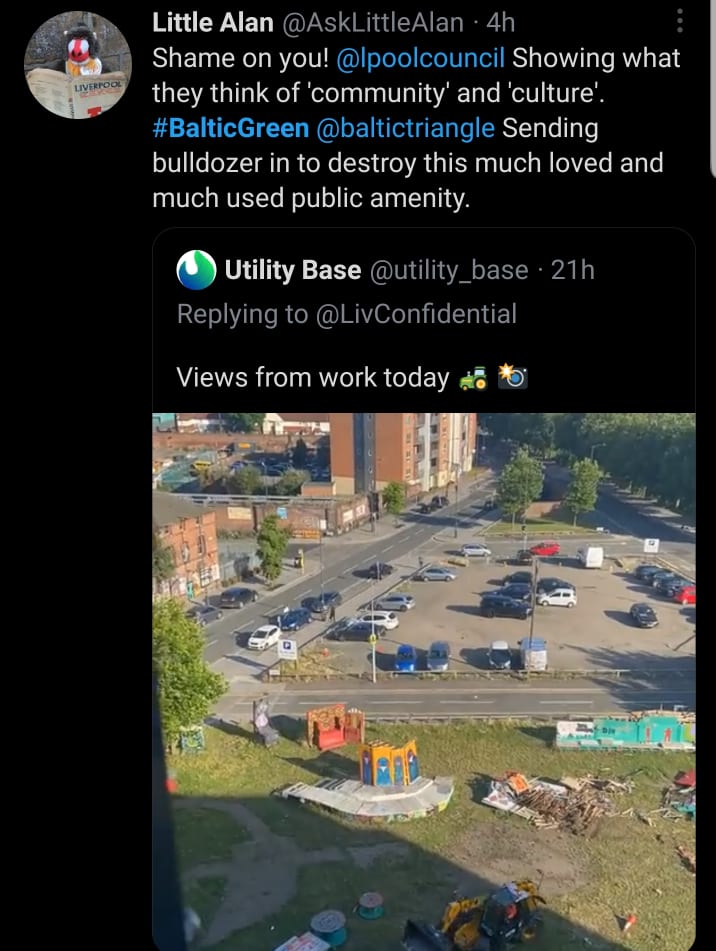

In the Baltic Triangle, the fear of looming gentrification is already starting to create displacement pressures and a sense of community loss. The rapid pace of development has initiated a narrative in alignment with Karsten’s statement that the city has become “the domain of young, childless households.” (2016, 76). The Baltic Green embodied social interaction and community development, such activities are key to counteract community erosion and instead empower a community to build social capital. Drawing on the interview with Tristan, he shared how the space was very useful for parents and guardians to “grab a drink and cake to sit on the green and chat” in the knowledge that their children were playing in a safe space. When the space was dismantled local residents took to Twitter to express their outrage, one resident exclaiming that Liverpool City Council clearly did not care for “community” or “culture” (See Appendix C).

These spaces for social connection are particularly important in neighbourhoods. One would assume that such civic action would be celebrated by the local council but, in this case, it seems to have been punished. Returning to the interview with Tristan, he summarised how in his opinion Liverpool City Council saw “People are problems to be resolved not a resource to be harnessed”. City planners should perceive the growth of the city in a balanced and spatially responsive manner as a priority.

To compress the findings of this discussion section, it is clear that communication between the volunteer group and Liverpool City Council was not mediated in a productive manner. The evidence provided in the literature review attested that the Baltic Green adequately met the needs of the local community and most importantly the children’s access to urban nature. Despite the efforts of volunteers to install bins and ensure regular checks, there were still issues with the upkeep of the site. Yet, the ability of volunteers to prohibit the misuse of space is limited. Social control exerted on public spaces will not stop people who want to misbehave, if it were not at the Baltic Green, it would have been another open space in the city. Collaboration and communication with the Liverpool City Council prior to the dismantling of the site could have seen mutually beneficial outcomes for all parties involved.

6 Conclusion

How can Liverpool City Council more meaningfully shape a better world? By creating a city that offers streets, spaces, and facilities for all ages, abilities, and backgrounds to enjoy together. A child-friendly approach has the potential to unite a range of progressive agendas – including health and well-being, sustainability, resilience, and safety — and to act as a catalyst for urban innovation. Such emancipatory and intersectional elements of greening interventions were facilitated in the Baltic Green. This paper demonstrated this with the inclusion of primary materials including photos, interviews, and social media posts. Thus, the main argument in this paper deplores Liverpool City Council’s decision to dismantle the community-built urban park. The Baltic Green offered a space for children to interact with nature, engage in independent play, counteract sedentary and indoor lifestyles, and also an opportunity for community cohesion. In future urban planning and development plans, Liverpool City Council needs to better consider the needs and identities of children living in the city centre to create a just and prosperous city.

Alice Sparks

Brussels

[i] Keyword search included public green spaces, child-friendly cities, intergenerational space, community gardens, playable spaces, multifunctional green infrastructure, and playful encounters.

References

Arup. (2017). Designing for Urban Childhoods. London. Retrieved from https://www.arup.com/perspectives/publications/research/section/cities-alive-designing-for-urban-childhoods

Baró, F., Camacho, D., Pérez Del Pulgar, C., Triguero-Mas, M., & Anguelovski, I. (2021). School greening: Right or privilege? Examining urban nature within and around primary schools through an equity lens. Landscape And Urban Planning, 208, 104019. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.104019

Campbell, S. (1996). Green Cities, Growing Cities, Just Cities?: Urban Planning and the Contradictions of Sustainable Development. Journal Of The American Planning Association, 62(3), 296-312. doi: 10.1080/01944369608975696

Chawla, L. (2015). Benefits of Nature Contact for Children. Journal Of Planning Literature, 30(4), 433-452. doi: 10.1177/0885412215595441

Hadani, H. (2021). By 2030, 60% of the world’s urban population will be under 18. Are our cities ready? [Blog]. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/07/building-better-cities-for-children-coordinating-within-and-across-city-agencies-to-harness-the-power-of-playful-learning#:~:text=By%202030%2C%20up%20to%2060,and%20health%20and%20well%2Dbeing.

Hart, R. (1979). Children’s Experience of Place. City University of New York.

Karsten, L. (2005). It all used to be better? different generations on continuity and change in s Geographies, 3(3), 275290. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280500352912

Karsten, L. (2016). City Kids and Citizenship. In V. Mamadouh, & A. van Wageningen (Eds.), Urban Europe : Fifty tales of the city (pp. 75-81). AUP. https://doi.org/10.26530/OAPEN_623610

Liverpool City Council. (2020). The Baltic Triangle Strategic Regeneration Framework. Liverpool. Retrieved from https://www.liverpoolbidcompany.com/wp-content/uploads/Baltic-Triangle-SRF.pdf

Nussbaum, M. (2013). Creating Capabilities. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Open Space. (2022). Retrieved 9 June 2022, from https://www.liverpool.nsw.gov.au/venues/parks-and-playgrounds/open-space

Oscilowicz, E., Honey-Rosés, J., Anguelovski, I., Triguero-Mas, M., & Cole, H. (2020). Young families and children in gentrifying neighbourhoods: how gentrification reshapes use and perception of green play spaces. Local Environment, 25(10), 765-786. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2020.1835849

Tillmann, S., Tobin, D., Avison, W., & Gilliland, J. (2018). Mental health benefits of interactions with nature in children and teenagers: a systematic review. Journal Of Epidemiology And Community Health, 72(10), 958-966. doi: 10.1136/jech-2018-210436

Weale, S. (2020). Youth services suffer 70% funding cut in less than a decade. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/jan/20/youth-services-suffer-70-funding-cut-in-less-than-a-decade

Appendix A – Map of Site

Appendix B – Interview Questions for Tristan Brady-Jacobs

- Chronological overview of all activity related to the Baltic Green, i.e., when did it start, what date were the council threats enacted, and what remains on the Baltic Green today?

- What were the original intentions (mission, goals, and outcomes) when you imagined the Baltic Green?

- Can you recall some of the feedback and experiences of visitors to the site? Here I want to capture the diversity of users.

- Having read the Baltic Triangle Strategic Regeneration Plan – they maintain the importance of public space to facilitate community cohesion and access to nature. They even comment that the ‘flourishing art scene’ ought to be celebrated. What went so wrong? Why was none of this appreciated?

- Why do you think it went so wrong?

- Clashed with the neoliberal agenda of Liverpool City Council

- Was not in unison with the gentrified image of the Baltic Triangle

- Simply an attempt for the council to assert their authority and deter other communication action groups from following in your footsteps

Appendix C – Additional Community Response to the Dismantling of Baltic Green

Leave a Reply