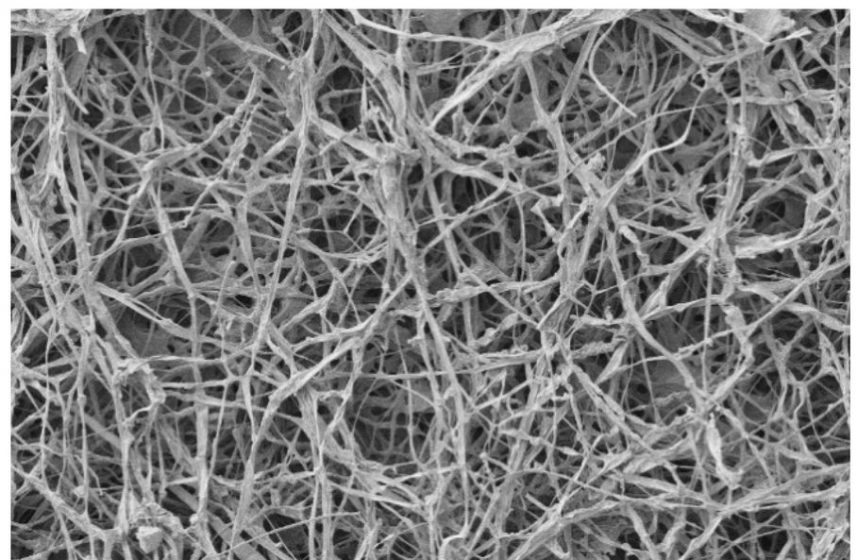

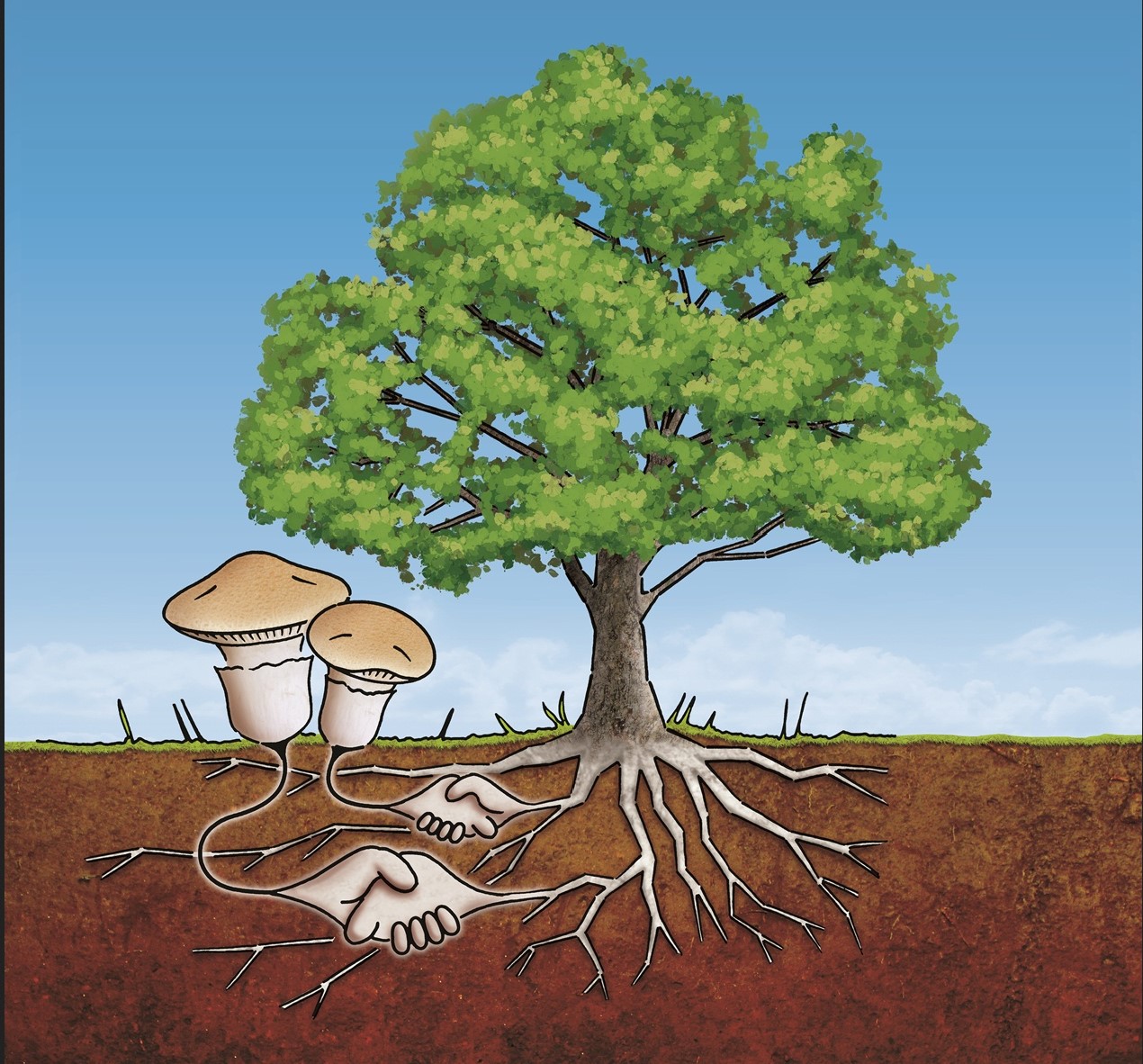

Fungi, that bizarre kingdom that includes yeasts and mushrooms, can be partnered with for healthier outcomes in urban natural areas and landscapes. Fungi, which are not plants and are more related to animals, are masters of chemistry. Enzymes created by fungi have been found to digest cigarette butts, DDT, and wood. They can transform wood into soil and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) into less toxic molecules. Working with fungi has almost limitless possibilities to improve plant health, break down urban toxins, and produce food and medicine from waste products. Mycorrhizal fungi, fungi that partner with tree roots, are integral to plant and ecosystem health. Fungi grow outward similar to plant roots but then can reconnect their hyphae (or strands of fungal tissue) moving nutrients in changeable directions. Their adaptable forms and networks are also a good model for a biophilic city. The mycelium, or the webbed collection of hyphae, can form vast networks. Using mycelium as a model for relationships, we humans can work in collaboration with fungi. Mycorrhizal relationships demonstrate that many species prosper with more connection and collaboration and that our world is mostly NOT a battle between opposing forces Partnering with fungi and soil has multiple benefits for our shared future.

Mycorrhizal networks

Mycorrhizal fungi intertwine with tree roots, exponentially expanding their nutrient capture capacity by ten to a thousand times. These fungi also connect to other plants creating an extensive and adaptable network in the soil, which can move nutrients from one plant to another creating a resilient web. In addition, mycorrhizal fungi produce glomulin, a sticky protein that helps bind soil particles together and enhances soil stability and health. This network is the foundation for ecosystem resilience and has been coined “nature’s internet” by mycologist Paul Stamets.

Approximately 95% of all vascular plant species form mycorrhizal relationships. This partnership has been seen in fossils of the very first land plants, dating back to about 460 million years ago. The fungi are the reason that the plants first survived at all on land, as the fungi produce enzymes that break down rocks and other substances into usable nutrients for the plants and themselves.

Research by Dr. Suzanne Simard and many others reveals how these fungi intertwine and entangle the whole ecosystem. “Mother trees”, as Dr. Simard calls them, are the pillars of the forested ecosystem. And it is the mycorrhizal network through which the wisdom of these oldest trees is able to communicate messages about pests, water, and nutrients. Mother trees are able to direct nutrients to their offspring via the fungal network and fungi can stimulate the growth of other microorganisms to protect the plants. When trees are connected to these networks die, they will transfer carbon and other nutrients to their neighbors via the fungal hyphae. Amazingly, this sort of shuttling of nutrients can happen between tree species, such as passing nutrients in the summer from a birch tree in the sun, to a Douglas fir in the shade, and then, in the winter, the Douglas fir will move nutrients back to the birch.

The interconnectedness of the plant-fungi relationship also expands to numerous wildlife. Maser et al, in “Trees, Truffles, and Beasts: How forests function”, explain how many forest mammals in present-day Australia and the United States are so dependent on mushrooms, specifically the underground reproductive structures produced by hundreds of species of mycorrhizal fungi called truffles, for their diet. Where I live in the Pacific Northwest of the United States, the western flying squirrel is one such truffle-seeking mammal (and it eats up to 100% of its diet in fungi during certain seasons). It digs for truffles in the soil and then glides its way from tree canopy to tree canopy using its wing-like skin between its legs. As these and other mammals and birds dig out and consume truffles, they are unknowingly dispersing the mushroom’s spores and further enhancing the mycorrhizal network.

Western-trained ecologists have for a while now known about the existence of these complex fungal networks, and we are finally realizing how a healthy network is so key to healthy forests. With this knowledge, there needs to be a shift in our frameworks of how we think about and steward the ecosystem, to one that promotes mycorrhizal network stewardship as a main driver. We can learn to team up with fungal networks to benefit our living systems, especially in urban areas that have experienced the most habitat degradation.

Fungi Practices in Urban Areas

Cultivating healthy fungal networks, rather than focusing solely on plants, is a paradigm shift that will take some experimentation and advocacy. There are large industries built on growing and nurturing plants, but only a few are dedicated to building mycorrhizal networks and building soil health. In landscape projects, soil is often neglected and rarely tested for its texture, compaction, or heavy metal composition. And testing for soil fungal and microbial community structure is possible but rare. Plants that thrive on a given site long term are matched not just with the microclimate but are an expression of the health and composition of the soil. The fungal and bacterial communities in the soil are an expression of soil health.

If the goal for an urban natural area is to establish native plant communities — this has been a major goal for most of my career — we need to put more value on the soil properties along with healthy fungal and bacterial communities. There are practices to improve the soil food web, but many of them have yet to become common practices in restoration.

Threats to mycorrhizae

The mycorrhizal network is dependent on living plants as well as soil organic matter. The disturbance of either one will result in hurting the mycorrhizae. Dense soils from vehicles and equipment compaction also damages soil health. This reduces the availability of space between soil particles for roots and mycelium to breath and grow, and also for mammals to burrow and dig. Herbicides, such as glyphosate, are also fungicides that can disrupt soil fungi.

Repairing soil

Healthy soil generally means high organic matter (usually 3-4% or higher), good aeration, a balance of nutrients as well as the right mix of sand/silt/clay along with abundant beneficial microorganisms. On a few of the sites I steward, I’ve been adding organic matter in forms of woodchips, biochar, and compost to amend soils. To loosen up imported soils, I’ve been using Dave Polster’s “Rough and Loose” technique. In landscaping and natural area projects with construction components, engineers and designers should treat soil and their mycorrhizae as critical for project success and continue to develop associated specifications.

Arbuscular mycorrhizae can be cultivated and many species are promiscuous as to what species they associate with, meaning one species of fungi can form connections with many different types of plants. It is possible to purchase mycorrhizae spores, but it could be an added benefit to cultivate spores from species that thrive in urban environments and magnify their abundance. Many techniques incorporate magnifying fungi, often times moving soil from healthy forests to newly planted or cultivated areas.

Korean Natural Farming is a technique that actively cultivates “indigenous microorganisms” to benefit crops by bringing mycelium and microorganisms from the forest into a farm field. We often transfer plants from more wild places into the city. Why not transfer mycelium the same way? Soil food web scientist Elaine Ingham promotes compost tea and other techniques to amplify microbial soil life. Rather than spraying weeds with pesticide, what if land stewards sprayed beneficial organisms on desirable plants? We are experimenting with using morel mushroom spore slurries and spawn to inoculate constructed beds of sawdust. Our hope is that the morel mycelium will feed on the sawdust substrate and gradually form a symbiotic relationship with surrounding trees, expanding the food web for the trees and expanding the mycelial network. And if this trial does succeed, who is going to be against having a harvest of morels?

Non-mycorrhizal fungi can also enhance soil quality and improve plant health. The Queen Stropharia mushroom (Stropharia rugosoannulata) is widely available and can produce large edible mushrooms weighing up to 2.25 kg grown on wood chips and straw. Woodchips can be used as a mulch around plantings and the fungi can benefit surrounding plants. This species breaks down toxins, reduces levels of E. coli, and shoots out spikes, called acanthocytes, that impale nematodes! This fungus feeds on both wood and animals! Many nematodes eat plant roots, so this fungus and other nematode-consuming fungi (like the oyster mushroom) can keep nearby plants healthy. Inoculated chips can regulate water and temperature around plants as well, improving growth. Queen Stropharia beds are easy to construct, a way to build soil and produce edible mushrooms for humans. If humans or other mammals don’t consume them, fly larvae will feed on the mushrooms which will in turn feed insectivorous birds or other creatures.

Although many mushrooms are edible, one should NEVER eat mushrooms that grow near roads or that are exposed to air, soil, or water pollution. Fungi can break down various toxins but can also hyper-accumulate heavy metals in their fruiting bodies. Fungi used for remediation purposes should never be consumed, but mushrooms grown on non-contaminated substrate will be safe. Mushrooms used for remediation should never be consumed, their mushrooms should instead be harvested and disposed of if found to have heavy metals.

Inoculating Dead Wood

Blown down trees or pruned limbs can be converted into mushrooms. I’m experimenting with drilling myceliated wooden dowels into dead wood. This will help break down the wood and add medicinal and edible mushrooms to the landscape. Matching the fungi strain with the wood species is important as is the time of year and care of the fungi. As mushroom foraging increases in popularity, why not have landscapes and nature trails in the city cultivated with mushrooms?

Cultivating fungi on dead wood can be part of fire reduction plans, as inoculated wood might break down faster than left to natural fungi for decomposition. Dead wood often develops mushrooms without cultivation and species like turkey tails (Trametes versicolor) and the split-gill (Schizophyllum commune) are common and medicinal.

Mycoremediation: Fungi for remediation practices

Fungi produce enzymes that are sent outside of their body to break down and digest surrounding materials. Lignin, the principal component of wood, is extremely hard to digest for most of the world’s organisms, but some fungi actually rely on lignin to survive. Because lignin has a chemical structure similar to some persistent human-created toxins such as PAHs, and PCB, we can use inoculated wood chips or straw as filters to break down road runoff or in other areas known to have toxic inputs. There is also mycoremediation potential for wastewater treatment systems where fungi can be used to break down pharmaceuticals and other hazardous chemicals that are usually not treated by conventional processes. There is a need for mycologists to be integrated into stormwater and wastewater treatment design to transform toxins into less toxic molecules for cleaner urban watersheds.

Fungi for the climate

Trees are often thought of as the natural carbon storage vessels of our planet, but soil-dwelling fungi play a huge role. Fungi produce compounds that are more persistent at storing carbon in the soil than any other organisms and their importance should not be overlooked. Fostering tree-to-fungi-to-tree connections can help support canopy health in cities. Climate resilience of urban trees is ultimately a collaboration between soil microorganisms, soil texture, hydrology, and tree selection.

Mushrooms for people and squirrels

As I shift my own awareness and focus to be a land steward for all Portlanders, fungi can be part of this equity work. My own shift includes humans as nature: we are part of nature and rely on its abundance. Part of stewarding land can be harvesting foods, medicines, and materials to reconnect to the land. Edible and medicinal fungi can be part of this stewardship and mushrooms like reishi, lion’s mane, oyster, and shiitake can be cultivated in natural landscapes. These mushrooms could be available to the lucky human or squirrel. Medicinal and edible mushrooms are already harvested by the public in cities. Why not add to their abundance?

The Future is Fungi

To shift to prioritizing fungi in natural landscapes, we need more mycologists. The City of Portland has a very detailed and vetted plant list, but no fungi list. Fungi have been a forgotten taxa for species lists, identification, and conservation, and developing a species list is a good place to start. Intentional mycological landscapes and mycoremediation projects have been created by interested community members, but it is time for governments and educational institutions to build up their own knowledge and experience. Ecologists, landscape designers, and land stewards can begin to learn about their biology as well as simple techniques to work with fungi.

There is huge potential to incorporate mycelium into urban natural systems and infrastructure. To brainstorm this potential in the Portland area, we have created a loose network of interested ecology professionals called the Mycelium Net-Working Group. This epistemic network will serve as a starting point among government and NGO land stewards to brainstorm potential uses of fungi, advocate for mycology projects, set up trials, share results, and educate ourselves and the public. Ideally, this will spawn innovative projects that lead to healthier and more inclusive urban natural systems and create a hub for resilience building. Not unlike a mycelial network! Community connections will be vital and learning the desires for medicinal or edible fungi in landscapes from different communities will need to be integrated into decision making. It is time to start building this infrastructure and I incorporating the fungal kingdom into our stewardship practices. It should be done in reciprocity, giving respect to the fungi and partnering with them to heal landscapes and communities. Working with fungi is a way to reconnect to the cycles of growth and decay and the web of the natural world. Changing our focus to protect mycorrhizal networks and encourage beneficial fungi will support resilient communities.

Toby Query

Portland

Recommended Reading:

Radical Mycology by Peter McCoy

Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Finding the Mother Tree by Suzanne Simard

Good morning.

I am writing to find out if you have mycelia of the following consumable mushrooms, please:

1.- Polyporus umbrellatus:

image.png

2.- Maitake (Grifolia Frondosa):

image.png

3.- Cordyceps Militaris:

image.png

4.- Enoki (Flammulina velutipes):

image.png

5.- Trametes o Cola de pavo:

image.png

Thank you for your time.

Fernando Rivera.

Very well written and informative!