A closer look at different types of social infrastructure helps to better understand challenges that stewards face and points to ways that strategies for visibility might support community investment and care.

As part of The Nature of Cities Festival, on 29 March 2022, a team of practitioners and researchers at NeighborSpace, Borderless, and the USDA Forest Service – Northern Research Station organized a seed session, entitled “Caring in Public,” to explore the building blocks of social infrastructure with a group of 27 participants from around the world. Starting from a synthesis of the literature and a case study of community gardens, we framed questions, synthesized concepts, and led an interactive exercise of diagramming visible and invisible systems that produce known benefits and outcomes that could be applied to multiple community-managed spaces.

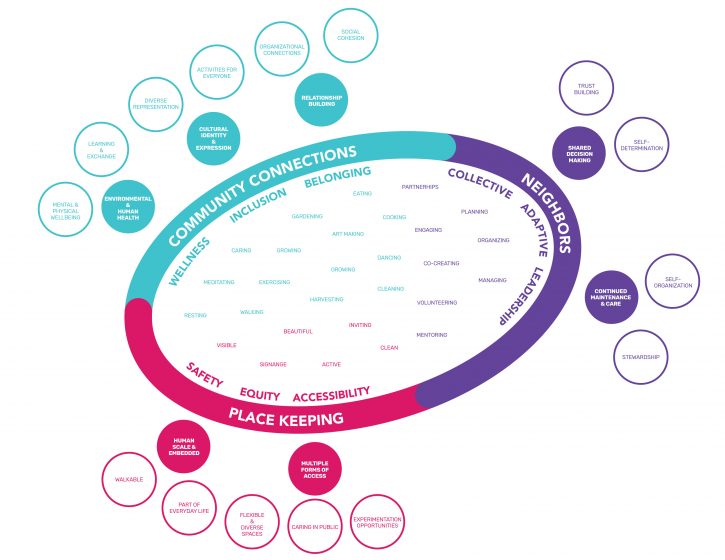

The framework was built around the example of community gardens and focuses on three connected themes:

- Neighbors: This theme relates to organizational aspects of the community ― the core and consistent caretakers, and the community leaders who are behind the scenes organizing people, building relationships with the broader community, planning both the physical space and activities, and identifying resources to support the community.

- Place-keeping: This is how the space is protected and held for the neighborhood, how the physical features of the space reflect the values and aesthetics of the community of caretakers and stewards. This also refers to the spatial typology, and their accessibility and communication systems.

- Community connections: This theme refers to the network of relationships and supporters that neighbors from community-managed spaces seek to develop to engage their community assets and resources. The stronger the network and the capacity for collaboration with other community groups, organizations, and initiatives, the greater the sense of belonging and inclusion.

These themes led us to map the existing activities and the conditions supporting the activities and to define the values, principles, and outcomes that are supportive of community-managed spaces, particularly community gardens.

We wanted to explore social infrastructure sites and systems, including community gardens, public libraries, alternative archives, street trees, and community fridges in order to test, refine, and reflect on our framework. To do so, we posed the following framing questions in our TNOC Seed Session:

- What are the physical sites and spaces in your city that support civic life and community care?

- Who are the groups and what are the governance structures that support these sites?

- What are the values and principles shaping these collective spaces?

- How do they do stewardship through specific practices and activities?

This essay is part two of a two-part series, click here to read part one.

Following an introduction to the framework and a community garden example, participants selected community sites of interest to them (e.g., libraries, parks, urban farms, publicly accessible private spaces) and went into break-out groups on zoom to brainstorm components and processes of these social infrastructure sites and systems at work. They went through three rounds of brainstorming on the activities, conditions, values, and outcomes of these sites – quickly covering their virtual whiteboards in sticky notes.

The aim was for participants to develop collaborative group models of various greenspace types and community spaces. By the end of the 90-minute session, we realized we were only just beginning to unfold key components and relationships in these spaces. The author team continued to meet and reflect after the session, sharing vignettes about our work, and observing patterns and differences across different sites and systems. This essay shares, reflects, and builds on what we learned throughout that process.

Different models and arrangements in social infrastructure, from publicly supported to community-managed to mutual aid

“Public” places exist on a spectrum of access from public rights of way to public parks and libraries to privately owned public spaces. Access to and possible uses of these spaces are shaped by who owns and manages them, as well as their location and enclosure (or lack thereof). For example, adults are sometimes not allowed in public playgrounds without a child, and university campuses within cities are often monitored by security guards who restrict access. Even in publicly managed parks and libraries, surveillance measures can make certain people excluded or unsafe ― specifically Black, Indigenous, and people of color, as well as queer people, folks with mental illness, and anyone from a community facing a history of police violence. These barriers can mean that the most marginalized are in some cases prevented from accessing the resources they need.

These spaces operate via different institutional structures and contexts ― well beyond the simple binary of ‘top-down’ or ‘bottom-up’ organizing. They include government-supported spaces, to ones in collaboration with institutions and organizations, to those that are actively counter-institutional or that expand how we conceive of institutional contexts. Below, we present five vignettes written by individual authors who are embedded in the sites and systems of community gardens (our original case), public libraries, community archives, street trees, and community refrigerators. A closer look at these different types of social infrastructure helps to better understand particular challenges that stewards face and points to ways that strategies for visibility described above might be applied to support community investment and care.

Plotting Care in Chicago Community Gardens

By Robin Cline and Ben Helphand

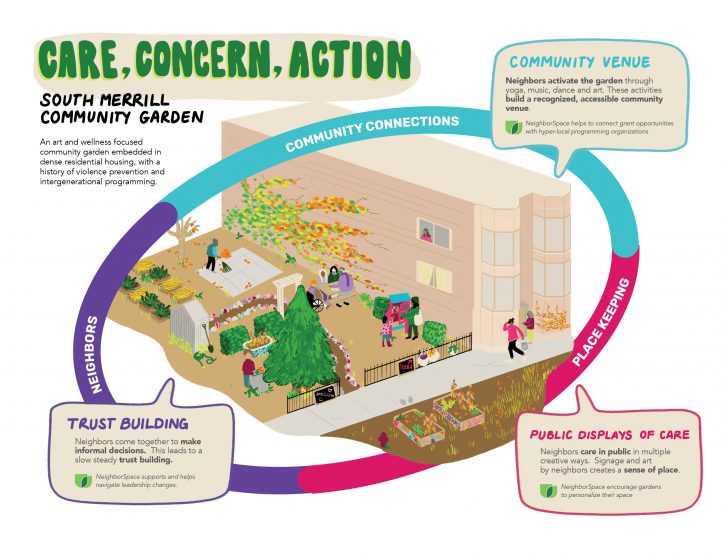

We at NeighborSpace are witness to the shifting of community governance over time. As a long-term land trust, watching change is one of the unique vantage points of our organization. South Merrill Community Garden is a powerful example of the shifting yet constant social infrastructure of a community space and was a key garden to illustrate using the modeling system described here.

South Merrill Community Garden, located in the South Shore neighborhood of Chicago, is an art and wellness garden long focused on violence prevention, health programming, and community healing. The garden holds 40-plus years of community open-space use; as is the case with many community projects, the space holds the memories of different eras of effort. In 1984, children and adults of the Genesis Cooperative and the Merrill Square Co-op came together to revitalize a vacant space of a former apartment building. Families removed bricks by hand and dedicated this lot for residents of the block to grow food and get to know each other. In 1997, after several iterations of different community leadership, the garden became the 6th garden of the now 130 gardens that are protected by the land trust NeighborSpace. In 2006, the garden was transformed again, this time into a living memorial for 10-year-old student Troy Law, a gifted student who died as a result of domestic violence. Through the efforts of a Mrs. Emily Kenny, a Chicago Public School teacher from nearby O’Keefe Elementary School, the garden still stands, with Law’s memorial sculpture bringing community members together to both honor and heal the community. From 2006 to 2014, the garden functioned with the support of the women’s auxiliary board of a nearby Methodist Church, one member taking particular leadership and investment, as her apartment overlooks the garden. In 2015, the Genesis Cooperative, coming full circle, again stepped in to support leadership and support at this garden. Today, the garden functions as a memorial garden and a gathering garden; a space to honor community loss, heal, and celebrate intergenerational joy. The garden leadership at Merrill uses consistent and visible intergenerational and youth public programming to invite neighbors in and, because of this, neighbors look to this space as a place for resources, and recognize it as a community venue. At the founding moment of this garden’s history, the garden was mostly a food and flower garden, but as Natalie Perkins, one of the garden leaders, puts it “ We learned we are better at growing community than growing kale!” While educational vegetable beds are still active, the garden group has shifted its primary attention to public programming that includes youth programs, art and music classes, cooking demonstrations, and yoga and dance programming.

The garden is embedded in the neighborhood between two large apartment buildings, with one of the former garden leaders’ apartments looking directly over the garden. Another leader is an active member of a housing co-op across the street, which is home to a community room, allowing for indoor programming and meeting space during inclement weather. Leadership at this garden has touched many institutions; originally founded and supported by O’Keefe Elementary School, the garden was later adopted by the South Shore United Methodist Church Women’s Auxiliary Board, in partnership with the local block club and the Genesis Housing Cooperative. Neighbors and stakeholders include both a local chef and an architect who helped design and build an outdoor oven space, with the support of garden members. While the community organizations that have adopted this garden shift in a cycle of care, the garden is always handed off with some connection and history still intact, which creates constancy during changing times.

The leadership of the garden is rather informal; the leaders have known each other for quite some time, are familiar with and like each other, and acknowledge that decision-making is a slow and steady process. “It sometimes takes a long time for us to make decisions, but that’s okay,” says Dianne Hodges, co-garden leader and community activist. Some leaders have more time than others and are able to meet contractors, artists, or other program providers in the space. They have adopted the process of video recording these meetings instead of taking notes to make sure the conversations are captured in their entirety.

This garden has a welcoming entrance, with flower beds and seating in their public parkway, as well as art sculptures and hand-painted signs. The garden is locked during non-use periods, but it is still sometimes used in ways other than intended (sleeping, alcohol, some vandalism). The garden addresses this with direct communication, invitation, and consistent positive presence. Care and maintenance of the garden usually occur during public programming hours and is not necessarily a separate activity.

The garden is open to unique partnerships – because several of the garden leaders work with community organizations, they are always on the lookout for volunteer groups and programming partnerships. They partnered for several years working with a hospital comprehensive care program to bring patients to the garden for health and wellness programs. They also co-program with a nearby NeighborSpace garden down the block to cross-pollinate their programs and increase outreach to neighbors. The garden receives grants when available to bring in artists and special programs. Since this public-facing programming is a major priority of the garden, the garden looks for relevant community cohesion grants (for example, in Chicago, yearly grants such as the Safe and Peaceful Communities Fund) to help keep community gardens activated with free seasonal programming. Grants such as these, as well as shareable models and explicit illustration diagrams, support the emerging and urgent recognition that community gardens are important sites of social infrastructure.

Public Libraries Contain Multitudes

By Natalie Campbell

Early on in my work with my local public library system — the DC Public Library in Washington, D.C. — an artist observed: “there are so many opportunities to take something out from the library, but almost no chance for the community to put something in.” Over the years — in shifting roles as a contractor, Friends group volunteer, and now as an employee at a public library developing exhibitions — I have contemplated these words, and how to create opportunities for more diverse and visible forms of participation within our public institutions.

From volunteering to voting to public service employment, there are plenty of opportunities to participate in a library environment, but the idea that a public library could — like a community garden — be a community-run space is far from reality. Like public parks, public libraries sit at the restrictive end of the spectrum of access for stewards, and possibilities for participation are highly regulated, with a variation on the system and branch level. At the bottom, this is because public libraries are managed by a board of directors with a great degree of accountability to their public. User privacy and personal freedom are rigorously protected. Data and community input sessions are used in all aspects of facilities and service design. And, of course, public funding structures vary greatly and shape the realities of how we experience public space. As more of the commons have become enclosed, public libraries have increasingly absorbed other social services, often without increased funding or staff. Libraries are also cooling centers, Departments of Motor Vehicles, disaster relief stations, job training hubs, and emergency shelters. The position of the library as a one-stop social service center has made these spaces more precarious and constrained (Ettarh, 2018).

Applying our framework to my own experience helps to illuminate some of the factors impacting practices of stewardship and care within public libraries. First, regarding sites and place-keeping: In contrast to community gardens, the physical sites of public libraries generally don’t offer members of the public opportunities to participate directly in design or care. Open sight lines, wipe-clean surfaces, Hatch Act proscriptions against political speech, and visual guidelines aimed at accessibility, safety, and inclusion are all factors.

In terms of governance and funding structures, even within the typology of public libraries, there is a wide variance. Public libraries in the United States are often, but not always, funded by tax dollars, but in most cases draw also upon other funding sources — state and federal dollars, grants, donations, fees, and endowments. The proportion of these in any given system can vary widely. For example, while a library card holder in DC may book any meeting room for a free public event with a library card (in accordance with their guidelines), conference rooms at the Free Library of Philadelphia are only available for non-library events via event rentals. Different definitions of public space and levels of access are produced by these realities.

The most common way that stewardship is practiced in the DC Public Library system is through volunteers and Friends groups. At the DC Public Library, each library branch has its own, independent, volunteer organization, with different structures and bylaws, loosely organized through a central Federation. Similar to the politics of Parent Teacher Associations, Friends groups grapple with issues of inequity and uneven participation across the city — while some branches have no active Friends group at all, the most active Friends group in the system, the Friends of the Mt. Pleasant Library, raised more than $100,000 in a single year through a t-shirt campaign that tapped into the local punk subculture and went viral, shipping t-shirts to punk rock/library lovers nationwide.

As we proceed with examining barriers to access and the self-determined spaces that have sprung up to “fill the gaps”, it is important to note that, within these larger top-down entities, there is an entire ecosystem that contains a variety of smaller, collectively managed spaces and initiatives. Some examples that speak the spectrum of management include the New York Public Library’s storied Picture Collection, which staff and supporters have rallied to maintain as an open-access circulating collection; The Go-Go Archive and Punk Archive at the DC Public Library (collections with a high degree of donor involvement within the public library’s archival collection); the innovative artist residency, exhibition space, and makerspace, The Bubbler at Madison Public Library; San Francisco Public Library’s teen-designed and led space The Mix at SFPL, to name just a few. Such examples are more the exception than the rule, in institutions tasked with equitably providing a dizzying array of social services. Yet, both within these more collectively managed initiatives and beyond — despite the strains on the system and restrictions on use — I regularly observe a sense of public ownership that renders public libraries palpably, strikingly different from almost any other interior urban space. Given this, how can public libraries learn from stewardship support structures in play elsewhere in our society?

Some questions that arise in relation to our framework: How can libraries empower ‘neighbors’ to play increased roles in decision-making, in a way that is accessible and equitable? How can we increase opportunities for residents to directly shape library spaces through place-keeping in ways that are equitable and sustainable for staff under numerous pressures? How can we better nurture and mutually strengthen the community connections that are occurring in all levels of service on a daily basis?

An Alternative Archive is a Collection and a Collective

By Nora Almeida

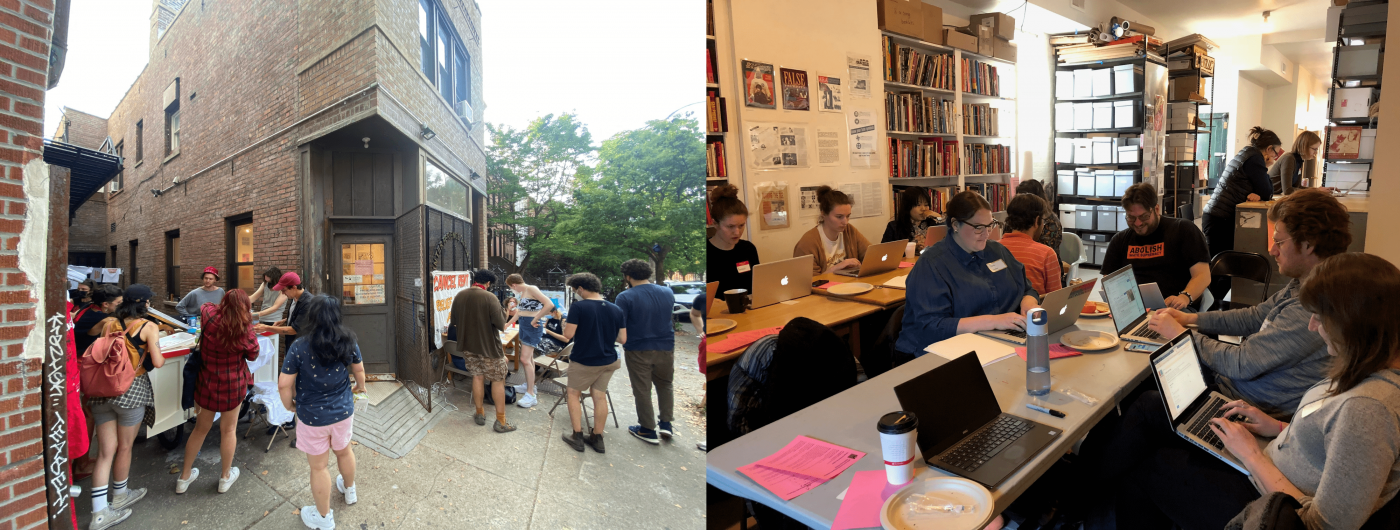

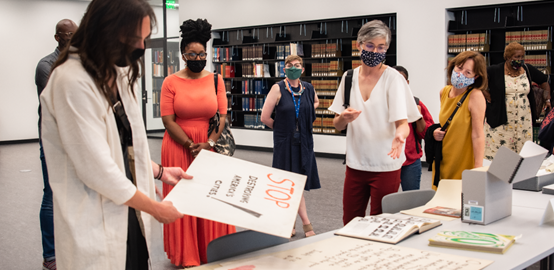

Image two: Interference Archive Wikipedia Editathon in collaboration with Wikimedia NYC, 2019, both by Nora Almeida

Alternative libraries and archives have emerged because of limitations and restrictions in municipally managed space. They are spaces that can support civic life and provide resources that you might not find in a public library or institutional archive or be set up in a rural area or underfunded neighborhood without adequate resources to meet community needs. Alternative libraries and archives vary widely in scope, focus, and type. They might be temporary, like the People’s Library which was created to support Occupy Wall Street activists. They might be itinerant pop-ups like Radical Reference, which emerged during the 2004 Republican National Convention to help protesters and later became an online volunteer reference service for information-seeking activists. They might provide access to non-traditional materials, like the Next Epoch Seed Library, which collects and “lends” the seeds of weeds that thrive in environmentally disturbed areas and publishes educational resources about urban ecology including open-access curricula.

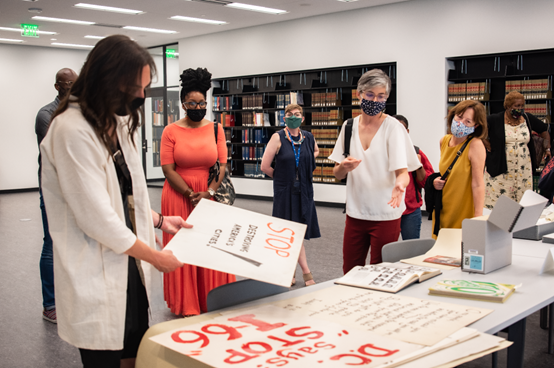

Many self-determined, independent libraries and archives create social infrastructure to support specific publics, provide access to counter-histories that are typically under-represented in public libraries and municipal archives, and function as community centers and safe spaces. Interference Archive is one example. Founded in 2012 in Gowanus, Brooklyn, New York, the archive is a donation-supported, volunteer-run space that mounts public exhibitions, offers free workshops and cultural events, and provides access to materials created by social movement activists from all over the world (“About us”).

I started volunteering at the archive in 2015 after attending a film screening with a friend and viewing an exhibition about Tenant Organizing. During my first volunteer shift, I helped with an outdoor printmaking event organized in collaboration with Mobile Print Power, a multigenerational printmaking collective, and Combat Paper, an organization that works with veterans to transform military uniforms into paper as a method to process and share experiences of war. In the seven years I’ve spent as an archive volunteer, I’ve organized dozens of public programs and Wikipedia edit-athons, co-curated four exhibitions, worked with educators and organizations across the city to bring movement histories into classrooms and galleries, and collaborated with grassroots groups like the No North Brooklyn Pipeline Coalition and The Poor People’s Campaign to host propaganda parties where we produce materials ― buttons, posters, t-shirts, banners ― for use in current movement struggles.

In contrast to most archives, Interference Archive is open stacks and treats the cultural ephemera produced by activists as part of a common history we all share, which is reinforced by a “use as preservation” philosophy that privileges the sharing of ideas over the preservation (or fetishization) of artifacts. Exhibitions at the archive are intended to make social movement histories more accessible and to encourage visitors to open up boxes and start conversations about contemporary struggles for social justice. Many of the exhibitions and almost all of the public programs at the archive are collaborative and interactive; they often support ongoing struggles directly by providing a forum for organizers to share ideas or indirectly through alternative educational programming (Gordon, Hanna, Hoyer, Ordaz, 2016). The archive is a generative space that is actively invested in archiving the present and regularly hosts programs including training, workshops, and media-making events to create material for use by NYC activists in street demonstrations (Almeida and Hoyer, 2019).

What drew me to Interference Archive and has kept me engaged is the relationships I’ve made with other volunteers and activists across New York City. The non-hierarchical governance and transparent work structure makes it possible to co-organize meaningful public programs without the kind of bureaucracy that I face in my job as an academic librarian at a large public university. I’ve learned an enormous amount from the material in the archive which represents a wide array of ephemera produced by activists around the world. In the archive, you might find posters produced by Dutch Provo anarchists during the 1960s advocating for car-free cities, pamphlets and flyers made by counter-globalism activists during the 1999 Seattle WTO protests, educational pamphlets made by the Jane collective–an underground abortion network in Chicago founded in 1965, issues of the Black Panther newspaper from the early 1970s covering the Vietnam War, Black Liberation solidarity posters produced by the Fireworks Graphics Collective during the 1980s, flyers made by anti-nuclear activists in the 1990s at the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp in the UK, and silk-screened t-shirts produced at the archive last week in collaboration with current organizers from Brooklyn Eviction Defense.

The sense of community the archive fosters ― among volunteers, across movement groups, and with visitors who range from students and scholars to curious passersby and activists ― is the product of the behind-the-scenes labor we all conduct to make decisions collectively and intentionally (even if they take a long time) and a commitment to support each other and new volunteers through transparent accountability structures that we’ve carefully developed over the past decade. The values and principles of the space are directly informed by the collective, non-hierarchical organizational structure practiced by many movement groups represented in our collection. Not unlike most self-managed spaces, we face limitations: our labor is unevenly donated and sometimes invisible, communication across a large volunteer network can be unwieldy, funding is precarious, and sometimes knowledge is lost as people cycle in and out of the network. These obstacles only reinforce the need for continual examination of social infrastructure models. After more than a decade, the archive has become more reflective of its own practices and limitations and is currently focused on developing programs to engage new publics that we aren’t currently reaching and refining organizational structures with an eye towards sustainability. Its role as a place made for and by the community, and the uniqueness of the collection material at the archive, means that it must, like any movement space, keep moving.

A Street Tree is a Place

By Georgia Silvera Seamans

It is easy to see a community garden as a place. You can enter and move through a garden. One can speak about spending time in and visiting a community garden. At first, it might be challenging to perceive a street tree as a place. Yet, when you consider these trees are often planted in demarcated areas of the sidewalk, they are physical places. Like a forest, they are also social spaces. Alone or with others, enabled by institutions or bucking conventions, you can do things in, with, and for a street tree. During my time as a community forester with the Urban Resources Initiative, a nonprofit housed within the Yale School of the Environment in New Haven, CT, most of the community groups I worked with created green spaces by planting street trees. Every group was composed of hyper-local residents with varying degrees of bonding and bridging ties who through stewardship strengthened their reliance on each other.

Acting out of a desire to reclaim their neighborhoods as beautiful, safe, verdant, spaces, residents applied for funding to develop and implement street tree planting plans. They collaborated with each other and with their community forestry resource person, scheduled workdays, showed up, dug and backfilled holes, and settled in their new trees with mulch and water. There were many such days throughout the summer. Each planting day and subsequent maintenance sessions were opportunities to display care, to deepen trust, and to embed new trees in the neighborhood’s canopy.

After digging in the soil with residents in New Haven, I moved to Boston where I stayed in urban forestry but had a more hands-off position managing the city’s street tree planting program. At that time, Boston planted trees based on residents’ requests for a new or replacement tree. I held a shovel a few times, posing in photos for corporate-sponsored plantings. Thankfully, selecting trees at a nursery was also part of the new job. It was an awesome responsibility to choose the trees for a city’s next arboreal cohort!

My next attempt at street tree care was with a trio of Honeylocust trees in New York City, but this engagement was short-lived. I was doing this work alone and didn’t have a community to lean on. I didn’t totally abandon the street trees in my neighborhood, though. I volunteered for the city’s 2015 Street Tree Census, the third decennial survey organized by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. I recruited a co-lead and we committed to a zone bounded by Houston Street, Sixth Avenue, 14th Street, and the Bowery. Annie and I participated in “train the trainer” workshops and hosted survey events for other volunteers. The census work was like a roving display of care. When we were out surveying trees, residents asked what we were doing which led to some fruitful conversations about the city’s urban forest.

Fast forward a few years and I had a plot on a university urban farm and several of the gardeners and the farm manager started talking about taking care of the adjacent street tree beds. We wanted to spread our resources beyond the farm’s fence and spruce up the public realm. These public trees were planted and left to negotiate space with human infrastructure, design, and other forms of mediated plant dispersal. We pulled spontaneous herbs, we cleaned up dog waste and garbage, and we sowed bulbs and native perennials. The location was challenging to care for. Without any fencing around the beds, the maintenance staff of the adjacent buildings piled heavy garbage bags on the new plants on trash collection days. People did not pick up pet waste. Litter blew into the beds. Squirrels ate the bulbs. We resolved to keep trying but then COVID-19 emerged, and our attention was diverted elsewhere. Two and a half years later, the garden community is slowly finding our footing. I enrolled in the Stewardship Team course offered by New York City Parks which reminded me of some of the resources available to care for public landscapes. I requested hundreds of daffodil bulbs, and one evening this fall, the main caretaker, a group of college students, and I picked up litter and planted one thousand bulbs at the farm’s edge and in adjacent street tree beds. This was a first step to rebuild our street tree care community. The next spring will be a time to consistently connect with our neighbors and reinvest in place-keeping. I want to mobilize the community around street tree care without attracting institutional interference and ideals of beauty.

Feeding Our Neighbors through Community Fridges

By Laura Landau

Public spaces take on a new meaning and level of necessity in times of crisis. In my past research, I have studied many examples of how parks, community centers, and houses of worship serve as flexible spaces that can be activated into emergency meet-up spots, donation collection hubs, and organizing centers following a disaster. Scholars have found that community needs and the chain of events following a crisis are often the same, regardless of the specific type of disaster event. Emergencies simply heighten and expose existing needs. The onset of COVID-19 in New York City reactivated the networks of civic groups, community leaders, local businesses, and elected officials that had been formed in response to a variety of other acute and chronic disasters, from Superstorm Sandy to ongoing chronic racism and gentrification. In addition, the pandemic brought a surge of new responders in the form of mutual aid networks, many of which are committed to working outside of systems of public aid and charity models that have strict requirements for who can participate and what they are eligible to receive (Landau 2022). Many mutual aid efforts have focused on food insecurity, a reality that predated COVID-19 in New York City but has increased by 36% since the pandemic due to a combination of income loss, rising costs for food and rent, and health and safety risks.

Community refrigerators (fridges) are one example of mutual aid that use public space to connect people with food in a low-barrier way. They are often located on the sidewalk, a public right of way that anyone can reach. Unlike many government and non-profit food assistance programs, community fridges do not limit or monitor the level of need each person can demonstrate, or the type or amount of food each person can take. They are also set apart from other models by the way they are stocked and managed. Anyone can put food in the fridge, and anyone can take it. This practice models a core principle of mutual aid, that everyone has something to give and something they need. In practice, navigating this principle can be complex. The role of neighbors is unique in this form of social infrastructure, because community fridges are usually managed by networks of people that are not explicitly connected to larger, more formalized organizations and nonprofits that come with resources and management skills. This allows for a great deal of organizing flexibility, but also can lead to conflicts over place-keeping, since anyone can place a claim on the public right of way.

As part of my dissertation research, I interviewed representatives from mutual aid groups across New York City that were formed in response to COVID-19. Many of the groups I spoke with operate community fridges, often in gentrifying neighborhoods with large low-income communities of color. All of these fridges depend on the unpaid labor of local residents, but other entities, both public and private, still shape their practice.

When one mutual aid group decided they wanted to create and operate a community fridge, a local beloved restaurant offered to purchase the fridge and keep it on their sidewalk. Almost immediately after being set up, the fridge was vandalized and broken. The restaurant owners were not dissuaded by the incident, and they purchased a new fridge and installed it on a crate so that it couldn’t be tipped over. With the organizing power of the mutual aid group, they have now maintained the fridge for over a year and a half. Volunteers operate on a regular schedule to pick up leftover food from restaurants, grocery delivery services, and the local food co-op, and stock the fridge and adjacent pantry with a mix of fresh ingredients and prepared items. Another team of volunteers regularly cleans out the fridge to remove any food that has gone bad. A group of college students brings leftover food from the dining hall. The operation has not been without its challenges — there have been a few other vandalism incidents and some volunteers have suspected that certain people are removing everything from the fridge and selling some of the food — but more often than not people are respectful. Where a charity model might view these incidents as problems to solve, the mutual aid group prioritizes the community’s right to food and does not believe in policing access.

When something does require intervention, mutual aid groups rely on their skills and networks to mediate. Another mutual aid group that operates a community fridge witnessed some ongoing conflict over food. In accordance with their values, the group wanted to help de-escalate the conflict without getting the police involved and potentially endangering the community. Although they are careful about their relationships with government representations and have in the past turned down offers of support from elected officials who wanted their endorsement or a photo opportunity in exchange, they were able to use their connection to a different elected to hire a translator to decrease conflict over miscommunication at the fridge. Similarly, in a different neighborhood, a disgruntled neighbor called the police to try to get a community fridge and pantry removed from the sidewalk, and a council member stepped in to defend the mutual aid group. These are just a few examples of many that illustrate the interconnectivity and interdependence of the civic, public, and private sectors in shared spaces.

In addition to providing food, community fridges can serve as points of connection. One mutual aid group asked a local art student to paint their community fridge to beautify the sidewalk space and reflect the culture of the neighborhood. Another volunteer shared an experience of going to stock the fridge and seeing an older woman waiting. The volunteer asked if there was something specific she was waiting for and discovered that she was hoping for a specific pastry that was sometimes delivered from the local bakery. Not only was it in the delivery haul, but it turned out to be the volunteer’s favorite treat as well, and the two were able to share a nice moment reflecting on their similar taste. While the transient nature of community fridges and the goal of allowing people some anonymity as they take their food sets them apart from other sites of social infrastructure, the loose social ties formed on the sidewalk are a crucial part of what keeps people coming back and working toward a city where everyone has the food they need.

Reflections and future work

Let’s return to the questions we posed at the outset of this essay as illuminated by these cases:

- What are the physical sites and spaces in your city that support civic life and community care?

- Who are the groups and what are the governance structures that support these sites?

- What are the values and principles shaping these collective spaces?

- How do they do stewardship through specific practices and activities?

These vignettes reveal diverse forms of social infrastructures in our communities. These “third spaces” ― beyond the home and the workplace (be they public, private, or in-between) ― are vital sites for providing/receiving social services, interacting with neighbors, and participating in civic life. In discussing how to adapt our framework beyond the specific site type of community gardens, we felt that the framework has many of the key components of any social infrastructure system ― the actors, the values, and the activities. But we need to consider the constellation of ways in which these dimensions come together. We can ask: who is caring for and using space for what and why?

We grappled with how to better capture key differences in organizational structures and institutional contexts across a wide spectrum ― from publicly-funded and staffed facilities to mutual aid networks. These differences have real implications for the role of paid and unpaid labor, the power dynamics of decision-making, and the control of space. Governance questions — Who decides? Who funds? Who labors? Who cares? — are crucial to pose and make transparent when seeking to understand these dynamics. As the vignettes reveal, there is complexity even within a single site type as publicly-funded spaces can include “friends of” groups and community-organized programs and activities.

We also identified constraints, challenges, and limits on the use of spaces and social infrastructures. As discussed earlier, access to sites varies widely across public and private spaces, with a whole range of configurations that might be described as “quasi-public” or public for some people, some uses, and in some instances. Particularly where we see commercial ventures that require purchasing an item or a service (e.g., coffee shop, restaurant, bookstore) ― this presents barriers for those who cannot afford to pay to access that space. Some sites and systems present challenging tradeoffs. For example, is an “open street” that activates a city street for an outdoor restaurant a transformation that invites publicity and conviviality, or is it one that privatizes space and excludes some users? The answer, frustratingly, may be “both” ― and being attuned to subtle and not-so-subtle acts of inclusion and exclusion are critical. Access also depends on the identities and bodies of the users, with lower-income people, people of color, and unhoused people more frequently surveilled and policed within “public” spaces that sanction certain activities (e.g., sleeping, solicitation, vending).

In focusing on positive social benefits in our framework, these challenges can recede into the background ― and yet they can be some of the main factors that differentiate between systems. We must pose the questions: Who is seen as the public? Who is served? Who is left out? Given these questions, how might we build even more complete frameworks that both celebrate the hidden benefits, but also acknowledge challenges and conflicts ― including dimensions of inequity, inequality, and injustice that thread through these systems? Going forward, how do we recognize the multiple values of these social infrastructures, and how might we better support and enable them? What unique forms of support might be needed in the context of stresses ranging from fiscal crises to climate change to pandemics? Building on national conversations about deferred maintenance and needed upgrades to physical infrastructures, what would a comprehensive plan look like to support, grow, and transform social infrastructures to meet the needs of all people.

Lindsay Campbell1, Robin Cline2, Ben Helphand2, Paola Aguirre2, Sonya Sachdeva2, Natalie Campbell3, Nora Almeida1, Laura Landau1, Georgia Silvera Seamans1

New York1, Chicago2, Washington D.C.3

Acknowledgments: All Partnerships Lab participants and TNOC Festival Caring in Public attendees, including Erika Svendsen, Michelle Johnson, Sophie Neuhaus, Sarah Fox Tracy, Bep Schrammeijer, Paula Acevedo, Pete Ellis, Gitty Korsuize, Tuba Atabey, Neda Puskarica-Stojanovic, Yaritza Guillen, Natalie Perkins, Staice Martin, Francesca Birks, Samantha Miller

about the writer

Robin Cline

Robin Cline serves as Assistant Director of NeighborSpace, an urban open space land trust in Chicago. Robin is also the part-time executive director for the art group OperaMatic, a site-specific artist group that activates public spaces in Humboldt Park and Hermosa with participatory art.

about the writer

Ben Helphand

For more than twenty years, Ben has focused on ways to help communities have a direct hand in the creation and stewardship of the built environment. He is the Executive Director of NeighborSpace, a nonprofit urban land trust dedicated to preserving and sustaining community-managed open spaces in Chicago.

about the writer

Paola Aguirre

Paola Aguirre Serrano is an urban designer and partner at Borderless since 2016. She has served as Commissioner of Chicago Landmarks and the Cultural Advisory Council of the City of Chicago, and currently serves in the Scholarly Advisory Committee for the National Museum of the American Latino. Paola received a B. of Architecture from the Institute Superior de Arquitectura y Diseño de Chihuahua, and M. of Architecture in Urban Design from the Harvard School of Design.

about the writer

Sonya Sachdeva

Sonya Sachdeva is a computational social scientist with the US Forest Service in the greater Chicago area. She utilizes machine learning and other computational methodology to understand the socio-cultural factors that shape environmental values and behavior.

about the writer

Natalie Campbell

Natalie Campbell is a curator, exhibit developer, and part of the DC Public Library Exhibits team. She has consulted on art and exhibits at the DC Public Library since 2016, including the MLK Library’s permanent exhibit Up From the People. She studied Art History at Hunter College CUNY and has taught at the Corcoran School of Arts + Design at George Washington University and the Maryland Institute College of Art.

about the writer

Nora Almeida

Nora Almeida is an urban swimmer, writer, performance artist, librarian, and environmental activist. She’s an Associate Professor in the Library Department at City Tech and a long-time volunteer at Interference Archive. She has organized media-making workshops, public events, and street performances across NYC.

about the writer

Laura Landau

Laura is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at CUNY Kingsborough Community College in Brooklyn, where she teaches U.S. Government and Environmental Politics. Her research focuses on post-disaster community organizing and the ability of grassroots movements to create local social and environmental transformation.

about the writer

Georgia Silvera Seamans

Georgia lives and breathes city trees–with experience in New Haven, Boston, Oakland, and NYC, and a dissertation about urban forestry policy in Northern California cities. Georgia is the founder of Local Nature Lab and directs Washington Square Park Eco Projects where she designs urban ecology programs for New Yorkers of all ages.

References

Almeida, Nora, and Jen Hoyer. 2020. “The Living Archive in the Anthropocene,” in “Libraries and Archives in the Anthropocene,” eds. Eira Tansey and Rob Montoya. Special issue, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3, no. 1. DOI: 10.24242/jclis.v3i1.96.

Ettarh, Fobazi. 2018. “Vocational awe and librarianship: the lies we tell ourselves.” In the Library with the Lead Pipe. January 10, 2018. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2018/vocational-awe/

Gordon, B., Hanna, L., Hoyer, J., & Ordaz, V. 2016. “Archives, Education, and Access: Learning at Interference Archive.” Radical Teacher, 105, 54–60. https://doi.org/10.5195/rt.2016.273.

Landau, Laura. 2022. “Mutual Aid as Disaster Response in NYC: Hurricane Sandy to COVID-19.” Journal of Extreme Events. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2345737622410019.

Leave a Reply