To test and experiment with different forms of street transformations and greenery, tactical urbanism is increasingly being implemented. Here are three examples enhancing green and open space in Munich

Due to urban densification processes and increasing confrontation with climate change, cities face the need to organize their public space in efficient and sustainable ways that take current needs as well as those of future generations into account. The Green Infrastructure (GI) concept is a widely used concept, introducing various approaches to implement green elements in urban areas that provide a broad set of benefits and values with environmental, social, and economic purposes (Hansen, et al.,2019; Pauleit, et al., 2011; Sturiale, & Scuderi, 2019). More specifically, the European Commission defines GI as a “strategically planned network of natural and seminatural areas with environmental features designed and managed to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services such as water purification, air quality, space for recreation and climate mitigation and adaptation” (EC, 2019). One element of this GI concept is street transformations, particularly green street transformations (EPA, 2022). Streets make up to 50% of the urban built environment. Therefore, they provide great prospects for change in urban design and sustainability (Furchtlehner et al., 2022; Im, 2019; Pogačar & Senk, 2020; Rodriguez-Valencia & Ortiz-Ramirez, 2021). However, streets still mostly serve a motorized infrastructure – i.e., car lanes and parking spaces (Furchtlehner & Lička, 2019). Cities are thus considering street transformations to gradually redistribute the streets-space and prioritize pedestrians and bikers, and increase green spaces.

The recent COVID pandemic has pushed cities further to provide access to green spaces in dense neighborhoods. To test and experiment with different forms of street transformations and greenery, tactical urbanism is increasingly being implemented. It is defined as exploring with short-term, low-cost placemaking through bottom-up movements and civic collectivity. Pop-up public spaces, bike lanes, or green elements are installed as temporary solutions to tackle the lack of public space (Furchtlehner & Lička, 2019; Natividade et al., 2022; VanHoose et al., 2022). The attempt is to create a long-term change for the neighborhood despite the limited lifespan of the project. However, it is questionable whether longevity and a change in the behavior of the population can be achieved through such implementations. Particularly in recent years, the city of Munich has experimented with green street interventions such as pop-up bike lanes, summer streets, Kulturdachgarten, Parklets, and Schanigärten (Natividade et al., 2022). Besides the City Council of Munich, another major local player in such projects is the Green City e.V. This association is predominantly involved in experiments and developments around greening the city. This essay will discuss three projects of the Green City e.V. in Munich and critically assess the greening aspect and longevity of such short-term tactical urbanism.

Green City e.V. (2022a) aims to transform the urban living space to increase the quality of life within the city of Munich. The association was founded as a non-profit organization in 1990 and is one of the largest environmental organizations in Munich today. Green City e.V. is proposing several different programs around greening with a focus on participative urban design, clean energy, environmental education, and sustainable mobility. Through tactical urbanism, they are implementing around 150 events and temporary projects per year with more than 2,500 volunteers engaged in their projects. The NGO is politically independent and financed through funding, members, grants, and commissioned work. The main attempt is to engage as many citizens as possible for a greener and more livable city with the guiding principle of “fresh air, more green, less noise and air pollution – our Munich of the future, a Munich for the people”[1] (Green City e.V., 2022a). Green City e.V. organizes their projects around four pillars: (1) Mobility to enhance climate responsive and reduce motorized traffic, (2) Urban green to promote communal gardening, urban greening, and design, (3) Education and participation, and (4) Climate change mitigation and resource conservation. In terms of greening the city, current projects of the organization include the Wanderbaumallee, the Parklets, and the Quartierswende Lehel (Green City e.V., 2022a).

Three projects exemplify their capacity to enhancing greenery.

Wanderbaumallee

Die Wanderbaumallee (“walking tree alley”) is temporarily transforming neighborhood streets into green “alleys” or “avenues”. For the duration of six weeks, 15 trees are greening one street before being moved to the next location in an opening event. The project has proven its worth for the past 30 years, occupying over 60 different streets, and resulting in the planting of 150 permanent trees (Green City e.V., 2022b). The “walking tree alley” is always accompanied by a small exhibition on the values of trees for the microclimate, shadow provision, or aesthetics to educate users about environmental issues and urban greening (Green City e.V., personal communication, 3. June 2022). The overall goal is to raise awareness of the benefits of trees as providers of important ecosystem services, such as mitigating climate change, regulating runoff, reducing urban heat, air and noise pollution, as well as inciting physical activity (Baró, et al. 2019; Green City e.V., 2022b; Niemelä et al., 2010; Nesshöver et al., 2017). Green City e.V. is aiming for users to valorize the positive effects of trees in their streets and start initiatives to accelerate the greening process (personal communication, 3. June 2022).

Challenges for the Wanderbaumallee might include tree maintenance or whether they will permanently change the streetscapes of the neighborhood. For instance, the trees need to be watered daily during their stay. Green City e.V. (2022b) is therefore calling for neighbors, schools, and kindergartens to water and maintain the trees. According to the NGO (personal communication, 3. June 2022), this is usually no issue though as neighbors often apply for the “walking tree alley” at the district committee and are hence, quite invested and motivated for the project. With regards to the visions of Jan Gehl and Jane Jacobs, residents themselves can be advocates to reclaim and transform their own streets through active engagement (Gehl, 2010; Jacobs, 1961). This will further motivate users to go beyond the mere project of tactical urbanism and demand the planting of permanent trees. The Wanderbaumallee will obviously not create an immediate effect on the microclimate but start an initial process that will expand further. There are several cases where the “walking tree alley” generated a long-term green street transformation, e.g., in Schrenk– and Steinstraße, Hofgarten, or Kaiserplatz (Green City e.V., 2022b). Before the trees are stored during the winter, the final Wanderbaumallee for 2022 has been set up in Blutenburgstraße, where the district’s committee itself is pushing the city to extend the green band of adjacent streets, initiating the greening process with this temporary project.

According to an Austrian study, five out of ten neighborhood streets in Munich currently contain street trees. Even though this number is higher than in other cities – such as Vienna for instance – and streets are often planted on both street sides in Munich, there is still room for improvement (Furchtlehner & Lička, 2019). Baró et al. (2019) discuss that street trees often go unnoticed when considering ecosystem services of green infrastructures. Though, they provide essential benefits, particularly in dense urban fabrics with lacking free space to implement larger green elements. Consequently, “walking trees” should be set up even more to ignite a green transition in other neighborhoods of Munich.

Munich’s Wanderbaumallee has been deemed a showcase experiment due to its longevity of more than 30 years and resulting in several successful green street transformations. It even inspired other cities to realize similar “avenues” such as the walking forest in Stuttgart and the Wanderbaumallee in Cologne.

Parklets

A second project initiated by the Green City e.V. is Parklets. Parklets offers (temporary) solutions to small public spaces along the sidewalk by occupying street parking. With a wide purpose range, they incorporate greenery, street furniture, exercise equipment, or bike racks to enhance social interaction, promote active mobility, reduce motorized traffic, and increase biodiversity. Particularly when dealing with a lack of space, they provide alternative public and green spaces integrated into the existing grey infrastructure. Initially set up in San Francisco in 2005, Parklets have now spread across 80 cities (Lydon et al., 2015).

In Munich, they were first installed in a pilot project in 2019 due to the increasing pressure for public spaces. Under the management of Munich’s Department for Urban Planning and with the support of Green City e.V., several Parklets are now set up every year with various purposes and designs, such as seating areas, bike repairs, and play spaces. Private individuals can submit applications for special use to the district committee and even request a small budget (Green City e.V., 2022c; Landeshauptstadt München, 2022). While Green City e.V. (personal communication, 3. June 2022) acts as an intermediary and supporting party, citizens themselves are responsible for the design and maintenance. There are no precise specifications, but the NGO strongly advises the integration of green elements (e.g., flowerpots, smaller plants, or even trees). In comparison to Schanigärten, which ignites outdoor spaces for cafes, restaurants, and bars, Parklets cannot serve commercial purposes but are committed to offering open and accessible spaces (Green City e.V., personal communication, 3. June 2022).

Acknowledged as one of their Urban Green projects (Green City e.V., 2022c), it is debatable whether Parklets contain “enough” green to be considered as an actual green intervention. Green City e.V. could demand a certain amount of green elements to enhance the feeling of a green oasis or micro park and to increase the provision of ecosystem services. Moreover, it is arguable whether Parklets will push a permanent transformation given their short duration and low frequency across the city (Bertolini, 2020). A possible long-lasting effect might become apparent when Parklets have been created for several years. From last year’s experience, Parklets throughout Munich mostly got positive resonance, except for some complaints about noise and the loss of parking space (Landeshauptstadt München, 2022). In the long run, neighbors will hopefully appreciate the value of the generated spaces and the increased livability through these pocket parks. Besides the greening aspect, Parklets offer a great opportunity to experiment with alternative, low-cost open spaces in neighborhoods and respond to specific local needs (VanHoose et al., 2022). Currently, parking spaces account for around 20 % of Munich’s streetscape (Furchtlehner & Lička, 2019). Hence, there is a lot of potential for pop-up public spaces and green elements by reducing parking spaces.

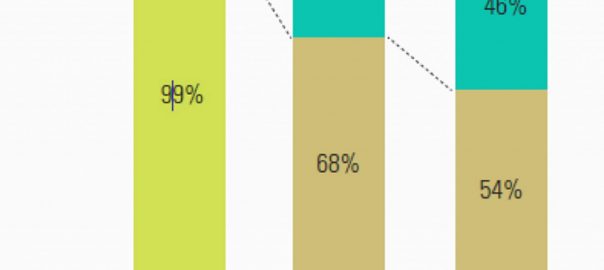

According to the WHO, residents should reach green areas within 300 m (WHO, 2017). Inserting pocket parks in dense neighborhoods can increase the accessibility to small green spaces (73 % of Munich’s residents have green spaces in 300 m proximity, Richter et al., 2016), and the availability of green spaces per capita (currently at around 19 m2, Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik, 2020). Therefore, Munich still has potential for development in terms of vicinity to green spaces. In conclusion, one Parklet will not achieve a green transition but, when placed more frequently and long-termed, and with a stronger focus on a greening aspect, they have the potential to transform the streetscape.

Quartierswende im Lehel

Finally, looking at a larger-scaled project of Green City e.V., the Quartierswende Lehel is attempting a sustainable, green transformation of the Lehel, part of Munich’s central district Altstadt-Lehel. It has quite a large share of green spaces. Part of the English garden, Munich’s largest park with 417 ha surface, is within the district and the river Isar limits the southern border (München.de, 2022). Nevertheless, the inner neighborhoods of the district are quite dense and built up with few green spaces (see visualization in Figure 3). This negatively affects residents as well as their urban environment, which is why Green City e.V. (2022e) is advocating a redistribution of the inner district’s spaces. By initiating three temporary pilot projects, they strive for greater, permanent solutions. The projects were implemented in a participatory action in close collaboration between policy, administration, and citizens’ representation. Ideas and designs were collected and voted on in the neighborhood to accurately reflect the needs of the residents and to surge acceptance and satisfaction. Proposals included ideas around green elements, gardening, street trees, or green facades. As a result, during the summer of 2021, tactical urbanism projects were implemented at three sites with a focus on greening the city: Isartorplatz was transformed into a park with green spaces, street furniture, and playgrounds. St.-Anna-Platz enabled space for participation and sustainable education around topics like urban gardening, blue elements, and sustainable waste management. And Mariannenplatz inaugurated an open space around a variety of different functions.

However, the Quartierswende also brought some challenges. Particularly Mariannenplatz did not get the expected approval. Instead of transforming the entire streetscape and affecting traffic circulation, only small Parklets were granted by the City Council (Priwitzer, 2021). It is surprising that the city administration is still reluctant to such measures when Munich is striving to be carbon neutral by 2035 in their Urban Development Plan 2040 (Landeshauptstadt München, 2021). The city needs these greening concepts to achieve its goals of urban resilience and sustainability, and to increase the share of green spaces in the urban landscape, which is currently at 12 % (Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik, 2020). Nevertheless, in the case of Lehel, the prospects seem positive after these tactical urbanism projects. Together with citizens and Green City e.V., the district committee is now striving for long-term solutions to initiate a permanent transition (Green City e.V., personal communication, 3. June 2022). However, critics claim that the Quartierswende might cause a process of green gentrification. Green gentrification is caused by the green transformation of a specific area, resulting in increasing rents and the displacement of lower-income groups (Gould & Lewis, 2016). Rent prices in Munich are already incredibly high, and this could even be aggravated. This will only show, though, once permanent developments have been executed.

Compared to the aforementioned projects of Green City e.V., the Quartierswende Lehel brings the largest scope and the most radical change. With a bit of risk and courage for change, the district – characterized by dense structures and grey infrastructures – could be transformed into a future-proof, green Lehel. A permanent transformation can then surge environmental benefits, enhance sustainable mobility, and expand social interaction and local identification.

Tactical urbanism and temporary green street transformations are increasingly applied to experiment with possible solutions for expanding green infrastructure and combating urban challenges. This essay discussed the extent of three temporary projects of Green City e.V. in Munich on greening the city and their prospects for permanent change.

Tactical urbanism projects offer citizens to transform their surroundings and reclaim the streets that are often car dominated. Implementing green elements can initiate a gradual transformation to increase the provision of ecosystem services and the quality of urban life. Moreover, they explore low-cost and low-risk measures, adapted to local needs. However, there is a chance that temporary projects might not result in long-term effects and the area will go back to the former status quo.

Green City e.V. initiates various tactical urbanism projects in the city of Munich such as the Wanderbaumallee, Parklets, and Quartierswende Lehel. The Wanderbaumallee moves 15 trees to a neighborhood street for a six-week duration. As a result, several streets were greened through permanent tree plantings. Parklets transform parking into public space in an attempt to generate a rethinking process. However, a green focus is not always achieved, and sometimes only small elements like flowerpots might be inserted, whereby a greening aspect could be pushed further. Finally, the Quartierswende Lehel explores placemaking and green interventions in a larger-scaled project of a central built-up district. Within the next years, citizens along with administrative organizations will plan the enduring development.

In conclusion, all three projects target a long-lasting green transition by exploring different forms of short-term interventions. While the Wanderbaumallee already caused several permanent tree plantings, both other projects are rather new, and their longevity is yet to be expected. Hopefully, all projects generate a rethinking process, where residents realize the benefits of green spaces in their neighborhood and claim for a permanent green transformation.

Leoni Vollmann

Brussels

References

Baró, F., et al. (2019). Under one canopy? Assessing the distributional environmental justice implications of street tree benefits in Barcelona. Environmental Science & Policy, 102, 54-64, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2019.08.016

Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik (2020). Flächenerhebung nach Art der tatsächlichen Nutzung in Bayern zum Stichtag 31. Dezember 2019 (A5111C 201900).

https://www.statistik.bayern.de/presse/mitteilungen/2020/pm307/index.html

Bertolini, L. (2020). From “streets for traffic” to “streets for people”: can street experiments transform urban mobility?, Transport Reviews, 40(6), 734-753. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2020.1761907

(EC) European Commission (2019). Ecosystem services and Green Infrastructure. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/ecosystems/index_en.htm

(EPA) Environmental Protection Agency (2022). What is Green Infrastructure? http://www.epa.gov/green-infrastructure/what-green-infrastructure#greenstreetsandalleys

Furchtlehner, J., et al. (2022). Sustainable Streetscapes: Design Approaches and Examples of Viennese Practice. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), 14(2), 961. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020961

Furchtlehner, J. & Lička, L. (2019). Back on the Street: Vienna, Copenhagen, Munich, and Rotterdam. Journal of Landscape Architecture, 14, 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/18626033.2019.1623551

Gehl, J. (2010). Cities for people. Island Press.

Gould, K., & Lewis, T. (2016). Green Gentrification: Urban sustainability and the struggle for environmental justice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315687322

Green City e.V. (2022a). Für ein grünes, lebenswertes und zukunftsfähiges München. https://www.greencity.de/verein/

Green City e.V. (2022b). Wanderbaumallee. https://www.greencity.de/projekt/wanderbaumallee/

Green City e.V. (2022c). Parklets: Mehr Aufenthaltsqualität vor Deiner Haustür!. https://www.greencity.de/projekt/parklets/

Green City e.V. (2022d). Parklets 2022: Sommeroasen im Münchner Straßenraum. https://www.greencity.de/parklets-2022-willkommen-in-den-sommeroasen/

Green City e.V. (2022e). QUARTIERSWENDE: Gemeinsam für ein grünes, lebenswertes und zukunftsfähiges Lehel. https://www.greencity.de/projekt/quartierswende/

Hansen, et al. (2019). Planning multifunctional green infrastructure for compact cities: What is the state of practice? Ecological indicators, 96, 99-110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.09.042

Im, J. (2019). Green Streets to Serve Urban Sustainability: Benefits and Typology. Sustainability, 11(22), 6483. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226483

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Vintage Books.

Landeshauptstadt München (2022). Parklets in München. München unterwegs. https://muenchenunterwegs.de/parklets

Landeshauptstadt München (2021). Nachhaltige Stadtentwicklung in München. Muenchen.de. https://stadt.muenchen.de/infos/nachhaltige-stadtentwicklung-muenchen.html

Lydon, M. et al. (2015). Tactical Urbanism. Island Press.

München.de (2022). Lehel: Alle Infos zum Münchner Stadtteil. https://www.muenchen.de/stadtteile/lehel.html

Natividade, V., et al. (2022). The morphology of placemaking – from urban guerrilla and formal street experiments to mobility and metropolitan regions. In: Annual Conference Proceedings of the XXVIII International Seminar on Urban Form. University of Strathclyde Publishing, Glasgow, 1335-1343. https://doi.org/10.17868/strath.00080521

Nesshöver, C., et al. (2017). The science, policy and practice of nature-based solutions: An interdisciplinary perspective. Science of The Total Environment, 579, 1215-1227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.106

Niemelä, J., et al. (2010). Using the ecosystem services approach for better planning and conservation of urban green spaces: a Finland case study. Biodiversity and Conservation, 19(11), 3225-3243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-010-9888-8

Pauleit, S., et al. (2011). Multifunctional Green Infrastructure Planning to Promote Ecological Services in the City. Handbook of Urban Ecology, 272-285. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/

Pogačar, K., & Šenk, P. (2021). Sustainable Transformation of City Streets – Towards a Holistic Approach. In: Rotaru, A. (eds) Critical Thinking in the Sustainable Rehabilitation and Risk Management of the Built Environment. CRIT-RE-BUILT 2019. Springer Series in Geomechanics and Geoengineering. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61118-7_24

Priwitzer, C. (2021). Vision trifft Realität: Wo die Quartierswende ins Stocken gerät. MUCBOOK. https://www.mucbook.de/vision-trifft-realitaet-wo-die-quartierswende-ins-stocken-geraet-superblocks-lehel-westendkiez/

Richter, B. et al. (2016). Analyse von Wegedistanzen in Städten zur Verifizierung des Ökosystemleistungsindikators „Erreichbarkeit städtischer Grünflächen“. AGIT – Journal für Angewandte Geoinformation, 2, 472-481. https://doi.org/ 10.14627/537622063

Rodriguez-Valencia, A., & Ortiz-Ramirez, H. A. (2021). Understanding Green Street Design: Evidence from Three Cases in the U.S. Sustainability, 13(4), 1916. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/4/1916

Sturiale, L., & Scuderi, A. (2019). The role of green infrastructures in urban planning for climate change adaptation. Climate (Basel), 7(10), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli7100119

VanHoose, K. et al. (2022). From temporary arrangements to permanent change: Assessing the transitional capacity of city street experiments, Journal of Urban Mobility, 2, 100015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urbmob.2022.100015

WHO (2017). Urban green spaces: A brief for action. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/342289/Urban-Green-Spaces_EN_WHO_web3.pdf

[1] Own translation („Frische Luft, mehr Grün, weniger Lärm und Schadstoffe – unser München der Zukunft, ein München für Menschen.“ (Green City e.V., 2022a))

Leave a Reply