The Harrisons (Helen Mayer Harrison (1927-2018) and Newton Harrison (1932-2022)) are widely acknowledged as pioneers in bringing together art and ecology into a new form of practice. They worked for over fifty years with biologists, ecologists, architects, urban planners, and other artists to initiate collaborative dialogues. The works they made in various places from the second half of the 1970s stand as proposals for putting the well-being of the web of life first. The Harrisons’ visionary projects have, on occasion, led to changes in governmental policy and have expanded dialogue around previously unexplored issues leading to practical implementations variously in the United States, Europe, and Asia.

In writing and inviting people to contribute we sought advice and received extensive help from both the Harrison Studio/Center for the Study of the Force Majeure (CFM); from Kai Resche and Petra Kruse, curators and editors with the Harrisons (and also the Berlin branch of CFM), as well as from David Haley (who was the project manager for Casting a Green Net and Associate artist for Greenhouse Britain: Losing Ground, Gaining Wisdom (2007-09).

We offered the following passage from one of the Harrisons perhaps less well-known works as a prompt, encapsulating their approach

Trümmerflora, or rubble plants and trees, are a special phenomenon unique to heavily bombed urban areas. The bomb acts as a plough, breaking brick, mortar, metal, and wood into fragments and, in a single gesture, mixing these with earth from below. The earth often contains seeds, dormant from the time of first construction on the site, that may have been buried for a century or more. These seeds come to light, and those that can live in this new and special earth, grow and flourish. Other seeds, dropped by wind and by animals, also survive in limited numbers in this new soil, this rubble. Hence the name Trümmerflora, or loosely translated, rubble flowers.

Harrison and Harrison 1990 ‘Trümmerflora: on the Topography of Terrors’ in Polemical Landscapes California Museum of Photography pp 12-13

This 1988 work by Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison during a period of residency in Berlin emerged in response to overlooking the derelict site that had been the headquarter of the Gestapo, Storm Trooper, and Secret Service Operations, i.e. the bureaucratic center for the Death Camps and Labour Camps of the Nazi regime. Earlier attempts by others to create an appropriate monument or memorial to the horrors of this urban site had failed. As Jewish people, this site was hugely significant. However, the Harrisons characteristically turned their attention to a possibility of healing brought about through an ecological understanding of the site, creating a proposal that enfolds this history, the destruction of the infrastructure of terror reducing it to rubble, lending itself to new life through the forces of nature.

The contributors to this round table, including artists, curators, environmentalists, landscape architects, and scientists, have all reflected on what they learned from meeting and working with the Harrisons. For some, this starts with Portable Fish Farm: Survival Piece #III which caused a furore when it was exhibited at the Hayward Gallery in London in 1971. A number of others were involved in various ways (curator, environmentalist, scientist, artist, and project manager) with the Harrisons’ work Casting a Green Net: Can it be we are seeing a Dragon? (1998) made as part of ‘ArtTranspennine98’, a major regional collaboration between the Tate Gallery Liverpool and the Henry Moore Sculpture Trust. Others have much more recent experiences of Newton Harrison as he continued the practice, including curating an exhibition Eco-art Work: 11 Artists from 8 Countries for Various Small Fires in Los Angeles in 2022, and developing the work Sensorium.

The contributors to this round table, including artists, curators, environmentalists, landscape architects, and scientists, have all reflected on what they learned from meeting and working with the Harrisons. For some, this starts with Portable Fish Farm: Survival Piece #III which caused a furore when it was exhibited at the Hayward Gallery in London in 1971. A number of others were involved in various ways (curator, environmentalist, scientist, artist, and project manager) with the Harrisons’ work Casting a Green Net: Can it be we are seeing a Dragon? (1998) made as part of ‘ArtTranspennine98’, a major regional collaboration between the Tate Gallery Liverpool and the Henry Moore Sculpture Trust. Others have much more recent experiences of Newton Harrison as he continued the practice, including curating an exhibition Eco-art Work: 11 Artists from 8 Countries for Various Small Fires in Los Angeles in 2022, and developing the work Sensorium.

Contributors reflect on how working with the Harrisons in various different ways informed, changed, and developed their practices. Some talk about having the strictures of their respective disciplines and working practices lifted and their thinking transformed. Others talk about the love, the love between the Harrisons, and the wider empathy reaching beyond human-centredness that they engendered.

Leslie Ryan’s contribution touches specifically on the Trümmerflora piece as she was working with the Harrisons as a studio assistant during this period. She describes how, having studied Landscape Architecture and encouraged by the Harrisons scepticism of the profession to question of the limitations of her discipline, she was taken on a journey that profoundly changed her understanding of that practice, including “always looking beyond the spatial and temporal boundaries of here and now.”

Lewis Biggs, who was one of the curators of ArtTranspennine98, is one of two contributors who had experienced Portable Fish Farm in 1971. He too comments on the dynamic between Helen and Newton, but he also notes “being impressed with how the artists would pounce on specific words that emerged in the public workshops, and highlight them for further discussion” and their “their Rorschach process to ‘discover’ iconic images from maps.”

The other contributor who saw Portable Fish Farm is Simon Read. Simon Read offers one of the counterpoints or serious questions based on his experiences during the Greenhouse Britain project. Coming from a place-based practice he is somewhat troubled by the Harrisons’ willingness to develop a response to a place without having inhabited it. That being said, he acknowledges the point made by a civil servant at the time, that the Harrisons were “refreshing in that they feel able to unabashedly talk about the big idea.” As authors who also worked on Greenhouse Britain, it is interesting to reflect that the Harrisons’ focus was on the question of climate adaptation and how to draw attention to that, when all policy at that time was focused on mitigation. We worked for 2 years on the project, and the Harrisons visited the UK eight or ten times, each visit lasting perhaps 2 weeks, during that period. The project had been instigated by David Haley through a series of workshops held from Aberdeen to Devon. But in the context of the Lea Valley, one context that was featured in Greenhouse Britain, we knew it far less well than Simon did as a result of his three or more years focusing on it during the Hydrocitizenship project (2014-17).

The various contributions from people involved in Casting a Green Net open up the process. They include Lewis Biggs, curator; Les Firbank, ecological scientist; David Haley, artist and project manager; John Hyatt, artist and educator; Jamie Saunders, futures and policy maker, Richard Scott and Richard Sharland, environmentalists. Casting a Green Net was pre-emptive planning for the area across the North of England, recognising the diversity of soils and making a case for developing diversity of species and landscape types across the region. The work is archetypal of the Harrisons’ practice in the scale (addressing a region), in the timescale (understanding the Romans as part of the story of becoming), and in the ways that different sometimes conflicted voices are brought to bear on the issues. The refrain in the work is also a beautiful example of their poetry,

I said

If not here then elsewhere

You said

If here

then elsewhere will know how to proceed

Les Firbank, a scientist acknowledges not really ‘getting’ the way the Harrisons worked with maps, having students remaking them by hand at scale, until he saw the audience engaging. His observation of the way audiences physically responded to the large-scale maps, moving in and out, very engaged, is what persuaded him that this work was significant.

Richard Sharland, an environmental activist also involved, comments on the Harrisons’ differentiating ‘discussion’ from ‘dialogue’, and their consistent intention to keep the process open. But he goes on to say that planners invited to discuss the work “were surprised and intrigued that these artists from California had much more data about the unsustainability of human life in northern England at their fingertips than they did.”

Richard Scott, with a particular interest in wildflowers and meadows, highlights how the Harrisons’ approach related, amplified, and helped develop the approach of his organisation, Landlife, to developing sites for wildflower meadows.

John Hyatt, who was a Professor of Art at Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU) at the time, draws out the importance and functionality of the title of the work, the conversations and propensities that led to it, and suggests what it did for people, adults, children, experts, who encountered the work. David Haley, just finishing his MFA at MMU at the time, became project manager for the project, weaves the narrative across decades, linking Casting a Green Net with Greenhouse Britain as well as explorations in Taiwan and Central Europe. He positions the term ‘post-disciplinary’ as encapsulating this form of practice.

The issues which drive the need for approaches such as post-disciplinarity are picked up by Jamie Saunders, a policy maker and ‘futures’ practitioner. He talks about the importance of the “preferable, probable, possible, plausible”.

The dynamic between Helen and Newton comes to life in various ways across several pieces. Yangkura talks about a conversation with Newton in 2019 not long after Helen had passed away, a conversation that centred on the power of love to ride both good and bad times. Leslie Ryan and Barbara Benish both draw out the complex and sometimes fractious dynamics—the weaknesses as well as the strengths, Benish remembering, “Newton’s occasional amnesia towards female autonomy or ‘otherness’ in the room, [when] Helen would gently, or forcefully, pull him back in”. David Haley, reflecting on working with the Harrisons over many years, comments that this friction was sometimes performed, allowing an audience to recognise that the issues are conflicted and that disagreement is allowed. Benish describes the deep intergenerational dynamics of the Harrisons’ way of working that has led to the development of art Dialog/Art Mill, a not-for-profit organization working in sustainable education via the arts and sciences in the Czech Republic.

Ruby Barnett, the Harrisons’ Studio Manager, and Senior Researcher from 2017-2021, opens up the Harrisons’ process of ‘morning conversations’, a practice they developed from Adelbert Ames Jr – Ames believed that you should set yourself a problem before going to sleep and that your unconscious mind would work on it providing a solution in the morning. The Harrisons developed their practice of ‘morning conversations’ as part of their process of collaborating—Work Place was their contribution to Arlene Raven’s 1983 exhibition ‘At Home’ documenting ten years of West Coast Feminist art. Work Place was an installation representing the front room of the Harrisons’ own house. They inhabited the installation, beginning “…their day at the museum just as they normally do in their home in San Diego – with a ritual of coffee, meditation, and dialogue”. Ruby Barnett’s contribution also hints at the ways in which the Harrisons understood how, as Donella Meadows put it, dance with systems.

Some of these themes are picked up by Beth Stephens, who with her wife Annie Sprinkle, are artists, academics, and ecosexuals and who worked with the Harrisons on Green Wedding to the Earth (2008). The Harrisons provide the ‘wedding homily’ for this performative wedding. They came together to explore the potential of a Ph.D. program focusing on environmental art but Stephens predominantly recalls the experience of exploratory conversations that connected them in a process of give and take across shared interests.

Another aspect is picked up by Petra Kruse and Kai Resche, curators and editors of The Time of the Force Majeure, the career survey and Harrisons’ autobiography published in 2016. Petra Kruse and Kai Resche adopt the approach the Harrisons used to explain an intertwined story from two perspectives. While some contributors met the Harrisons and had their world re-framed, Kruse and Resche found in the Harrisons’ approach something they had been seeking.

Newton Harrison’s particular turn of phrase is captured in Janeil Engelstad’s contribution. Newton was involved with Billy Klüver’s Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) initiative at the end of the 1960s (as well as with the Los Angeles County Museum’s Art and Technology project in the early 1970s). Engelstad was co-curator on 9e2 Seattle, a programme revisiting the key questions and ambitions of 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, the one of the iconic parts of E.A.T. Engelstad included a discussion with Newton Harrison reflecting on Billy Klüver’s initiative, during which she reports, “He had it all wrong… and I told him thus…”

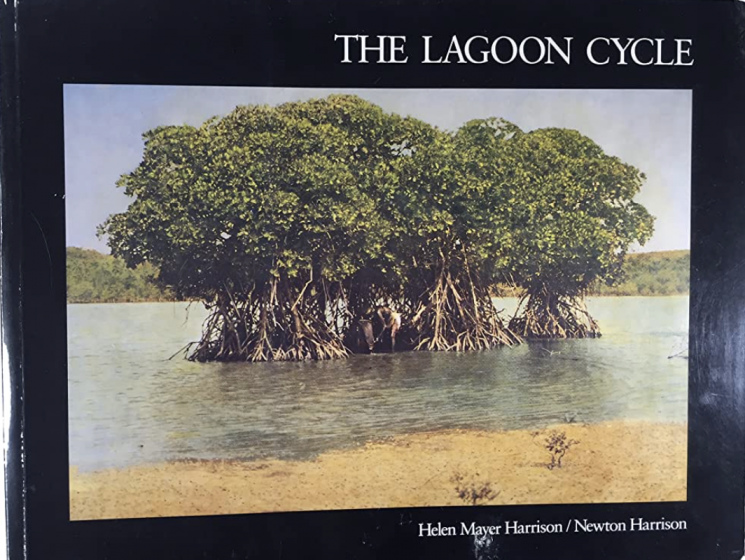

Ranil Senanayake is perhaps the longest collaborator who has contributed, having met the Harrisons in 1974. Senanayake introduced the Harrisons to the crab Scylla Serrata indigenous to Sri Lanka’s lagoons. The crab becomes the central ‘character’ of the Harrisons’ seminal work, The Lagoon Cycle, and Senanayake excerpts key passages from that work to narrate his relationship with the Harrisons during that period. He goes on to tell us about working with Newton again in Korea in 2021 and how their approach has informed his work in ‘analog forestry’, an approach he developed, which uses a synthesis of traditional and scientific knowledge to optimize the productive potential forestry. He also highlights EarthRestoration, a blockchain approach to supporting local farmers to grow trees. Using a tradeable digital ledger NFTs are issued providing farmers with an income for incorporating living photosynthetic biomass into their farms.

Aviva Rahmani, another contributor who knew the Harrisons from the early 1970s, highlights their ability to deconstruct power at scale, their support for an interest in her works over a lifetime. Rahmani was one of the artists Newton chose to include in the exhibition he curated for Various Small Fires. Other contributors to the same exhibition had only gotten to know Newton in the past 3 or 4 years. They included Salma Aratsu and Terike Haapoja. Both found their practices shifted by the experiences despite the short period of acquaintance. Arastu attributes to the Harrisons her own development in creating a feminist environmental position that can bridge science, art, and faith. Working with calligraphy she has become able to see a connection between the energy in natural systems and that of the lyrical poetry and patterns of Islamic art and the Qur’an. Haapoja focuses on Newton’s understanding of empathy as ‘feeling for’ and ‘solidarity with’ the more-than-human, particularly evident in the work Apologia Mediterraneo (2019), a work in which Newton addresses the increasing levels of industrial pollution in the Mediterranean Sea. She builds her understanding of empathy through Newton’s early experience of hearing the earth screaming in response to industrial forms of excavation.

Even scientists like Johan Gielis found that Newton Harrison in his late eighties knew the right questions to ask, in this case, whether the study of relations between individual organisms could inform continuity. Gielis, a Belgian mathematician-biologist, works on encoding the shapes and connections between organisms in search of a unified description of natural forms. They shared a starting point in holistic thinking in relation to the web of life, challenging and redirecting the ecocidal direction human society was and is currently taking. Gielis, like the Harrisons, works with metaphor [“switching between [heart] as a cylinder (for transporting blood) and a Möbius strip, a one-sided body for exchanging oxygen in the lungs and cells”], displacing old metaphors for new more appropriate ones. For Reiko Goto-Collins, working with her partner Tim Collins, it is Harrisons’ insights into metaphor as a dynamic critical tool that most struck her about their work. In particular, she retraces their pathway from dysfunctional metaphors, ‘flipping’ these to open up choice in the way we relate to the world around us, here explored through Collins and Goto’s research into the Scots Pine.

Ruth Wallen and Brandon Ballengée, both artists, outline the various ways they have learned from, been inspired by, and worked with the Harrisons. Ruth Wallen’s work for a residency at the Exploratorium in San Francisco was inspired by the Harrisons’ approach. She had followed their Masters and she also raises the importance of metaphor in their work. For example, Serpentine Lattice (1993), seeing a forestry practice as a lattice, identifies crucial points to begin processes of restoration. Ballengée’s current work Memory of a Cajun Prairie uses the same approach as the Harrisons’ Future Gardens works, asking what can adapt and what supports adaptation. It was developed in dialogue with Newton Harrison and embeds ecological research into the process of imagining what ‘scaffolding’ adaptation might mean in the Louisiana context.

Several contributors speak about the Harrisons as teachers in various ways. Tim Collins contributes a piece of writing originally developed in 2000 with the Harrisons, Jackie Brookner (1945-2015), Ruth Wallen (another contributor), and Josh Harrison. This text is a pedagogical proposal focused by the challenge of involving artists in civic discourse. It highlights in particular a lack of capacity in the languages and processes of ecology, politics, and sociology. This pedagogical proposal outlines in broad terms the challenge, “the emerging biological revolution is all but abandoned to the sciences” and outlines the requirements for a new approach to visual art education that would equip artists to participate in the global environment challenges. Twenty years on and whilst there have been multiple attempts at establishing such courses, they remain outliers and many have closed.

The character of this challenge is well articulated by Cathy Fitzgerald, an environmental scientist who has ‘transferred’ to the arts. She sets out her experience and the role of the Harrisons both as models and as empathetic and timely supporters. The lack of interest in the biological revolution and the unwillingness to recognise the value of engaging with the languages and processes of ecology and politics was a challenge for Fitzgerald throughout her studies at Masters and Doctoral levels.

Jo-Ann Kuchera-Morin, a composer and artist working in complex systems research, and her team including Dr. Gustavo Rincon, Dr. Kon Hyong, and Myungin Lee, met Newton in 2021 through the development of Sensorium. Their technology, AlloSphere/AlloLib has developed significant immersive environments engaging the public in matters of concern. Their work with Newton on Sensorium provoked thinking around how such an environment could function as a pre-emptive planning system, among other functions including education. Together they nurtured a culture of respect between researchers, one science the other arts “investigating the lifeweb from true empirical inquiry and truthful interrogation.”

Wu Mali was the instigator of the work that the Harrisons did with David Haley in Taiwan in 2008. Wu, as co-curator of the Taipei Biennial in 2018, included Newton Harrison’s On the Deep Wealth of this Nation, Scotland as a centrepiece of the exhibition. She comments, “many works pointed out the difficulties and challenges faced by the contemporary world, but the Harrisons demonstrated how we could apply wisdom to allow species to coexist and prosper.”

Tatiana Sizonenko, curator of the 2024 exhibition Helen and Newton Harrison: California Work, which will form the keystone of the fourth iteration of Getty’s Pacific Standard Time, highlights how the Harrisons’ approach informs her curating. Sizonenko had previously curated Art as Agency which combined the Harrisons work Peninsula Europe IV with works from younger artists influenced by them.

We have written extensively on the practice of the Harrisons, but this process of hearing the many different perspectives of artists; curators; landscape architects, environmental activists and policy makers; and scientists, has opened up new aspects of their practice. One of the fascinating aspects in the enduring connectivity over very extended periods involving ongoing dialogues as well as collaborations on multiple projects woven through this collection.

The other aspect that becomes clear from these different responses is the ways in which the Harrisons opened up their process to others. From the various contributions we can begin to understand how this enabled individuals to find themselves by being invited into the practice and being involved in the work. The pretty consistently recurring sense is that across the arts and sciences, even those who questioned the Harrisons’ approach, were able to engage with it and understand it, and able to develop their own approaches.

In one of the last published interviews with Newton Harrison he is asked what he would say to younger artists. He offers the following,

Let us forget originality. Let us forget our signature on our work. Let us begin to do what we do best, which is improvise with a new culture that will be covalent with the life web itself, and let’s get together and create. (Harrison, N., and KUPPER, O., 2022. Newton Harrison: Force Majeure. Autre Magazine, 13 Biodiversity. p.257)

Chris Fremantle and Anne Douglas

Ayrshire and Aberdeen

about the writer

Anne Douglas

Anne Douglas is a Professor Emeritus, previously Chair in Art in Public Life at the Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen Scotland. She has focused, over the past 25 years, on developing doctoral/postdoctoral research into the changing nature of art in public life, increasingly in relation to environmental change.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation