The Nature Futures Framework could support the creation of nature-positive scenarios for cities that should follow two important principles: First, consider the effects of actions well beyond the footprint of the city; second, consider equity in visions of the future.

Over the last few months, the metaverse has captured the attention of many professionals, including urban planners.

While some may fear a Spielberg-like scenario where we stop caring for our physical world, we can also think of the metaverse as a gateway to inclusion ― where most people could help shape cities from the comfort of their living rooms. This is what cities like Seoul envision, with large investments in the metaverse to improve civic services and lower barriers to participation in urban debates.

As this technology and other internet and communications technology (ICT) tools develop — fast ― can we leverage them to change how we design with nature in cities? Can they help develop biodiversity-friendly visions for the future?

Issues with existing nature-related visions

Frameworks that address the question of nature in and around cities are already abound. Some examples at the international level include the “Urban” Sustainable Development Goal, SDG 11, and the New Urban Agenda, which both promote greenspaces in cities: For example, SDG 11 proposes to measure the increase in the share of urban greenspace in a city to “provide universal access to safe, inclusive, and accessible green and public spaces”.

Multiple concepts taught in urban design and landscape architecture schools also paint optimistic visions centred around nature: Designing with Nature, Garden Cities, Biophilic Cities, and so on. All these have inspired greening policies in many cities around the world, including here in Singapore where we moved from a Garden city to a City in Nature in the course of a few decades.

Notwithstanding their contributions, these agendas and visions remain limited for shaping our cities’ nature-positive futures.

First, they typically offer general guiding principles or high-level targets that do not address on-the-ground challenges. For example, the goal of increasing the share of urban greenspace is laudable but insufficient when it comes to addressing complex trade-offs between land for transport, housing, and greenspace.

When concepts are more detailed, they lack an important dimension in that they do not reflect citizens’ values. Yet, for those visions to be legitimate, useful, and used, they need to integrate a plurality of worldviews about nature. In other words, recognizing that people hold different views related to nature, and therefore positive visions for the future of nature in cities will differ vastly between people.

In the “science-policy space, IPCC’s “shared socio-economic pathways” are other examples of narratives that embody various degrees of optimism ― or rather pessimism ― about our ability to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Although laudable, these pathways that make IPCC-scenarios relevant beyond climate models resulted in most scenarios being negative for nature. Probably not useful, therefore, as a tool for shaping hopeful futures for nature in cities.

Making space for positive and inclusive nature visions ―The Nature Futures Framework

Such diagnostic is what drove the development of the Nature Futures Framework by the IPBES working group on scenarios and models. The framework ― NFF in short ― was co-developed to emphasize the importance of plurality in scenario development. In this context, we do not let “experts” develop nature-positive scenarios but acknowledge that local values should drive this process.

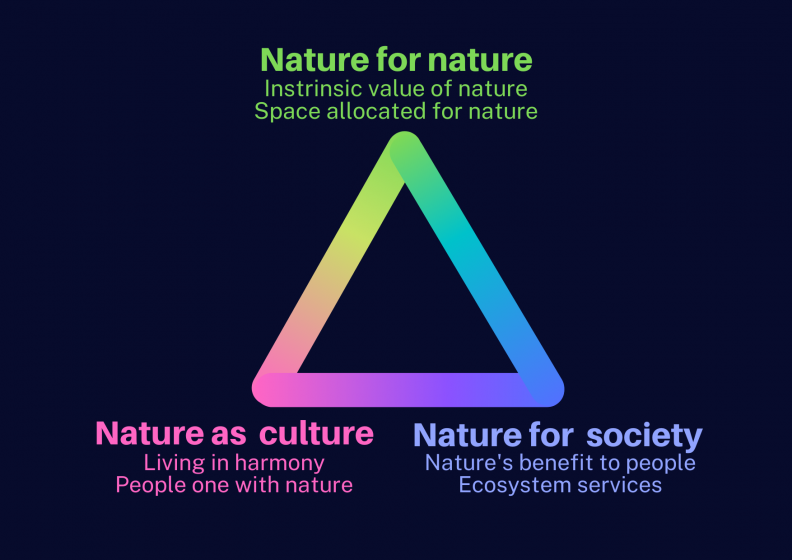

In practice, the NFF distinguishes between three types of nature-related values: “Nature for Nature” values, that recognize nature in and for itself (driving, for example, the protection of endangered species); “Nature for Society” values, that emerge from an understanding of the benefits nature provides to people (think promoting urban parks for people’s enjoyment); and “Nature as Culture” values, a fuzzier set of values having in common that they do not set people apart from nature, but rather embrace our relationship with nature (think educational programs developing a sense of nature stewardship in early age).

All these values have overlaps, and, as individuals, we likely hold multiple, perhaps conflicting, values ourselves. Yet, recognizing and mapping such values, for example, using the triangle below, will help understand individual and organizational perspectives on nature, negotiate potential trade-offs, or look for win-win solutions, where multiple types of values are promoted.

Using the Nature Futures Framework for cities

The NFF has only just started being applied as a visioning tool for cities, for example, urban growth scenarios in the Atlantic forest of Brazil.

In a recent publication, we explained how the framework could support the creation of nature-positive scenarios for cities: In addition to reflecting different types of values (“for nature”, “for society”, and “as culture”), scenarios developed with the urban NFF should follow two important principles: First, considering the telecoupling effects; i.e., actions taken in a city, such as reducing food waste, may have effects well beyond the footprint of the city, such as in agricultural expansion in sourcing countries. Second, considering equity in visions of the future, both through an inclusive participatory process and in designing for environmentally just futures that provide equitable access to the benefits of nature.

Recently, we also applied the NFF as a screening tool to analyse a particular “pool” of urban visions and determine whether some perspectives were missing. For example, my lab has analysed a set of serious games ― games with an educational or professional purpose ― to show that they were promoting “nature for society” values, and therefore painting a utilitarian picture of urban nature. Could future serious games be developed with a more balanced view of nature?

Similarly, we have used the framework to scrutinize visions for new towns in the Greater Jakarta Metropolitan area, through a masterplan analysis. By identifying the values associated with different visions and practices, we emphasized how new towns could inspire each other and become more “nature-positive” without necessarily involving more financial or land resources.

Both of these projects provide a mirror for existing practice and help researchers and practitioners design or re-design tools that will cater to a broader range of valid, nature-related values.

Yet another framework?

Is the NFF yet another tool to consider for cities interested in “building greener”? Yes… and that is fine. IPBES is one among many organisations ― with or without the UN system ― promoting participatory processes in urban governance. Its legitimacy and recognition will help the diffusion of the framework and will promote innovation, which is needed for local governments, NGOs, and civil society to accelerate the protection or restoration of urban nature.

Upcoming guidance will help promote the tool in the ways I described above and many other applications. Technology such as the metaverse can enable further applications, of course. As an intelligent urban thinker recently put it: “Urban practitioners should use AI in combination with other tools and methods, such as community engagement and stakeholder consultations, to make informed decisions about sustainable and inclusive urban development.”

But most importantly, NFF guidance will help the scenario and modelling community standardize lessons learnt through engagements and improve the usefulness of the NFF in future applications. It will promote the creation of toolkits and capacity-building materials critically needed for cities with lower resources. While megacities typically have capabilities to catalyse the work on urban nature, secondary cities may benefit from more resources and tools to effectively implement participatory processes for urban nature.

Secondary cities do not have millions to invest in the metaverse or expensive technology but they have real-world issues to address regarding the use of a precious resource: land. With the expected urban population growth, especially in Asia-Pacific, it is critical to provide urban actors with resources to articulate future visions and develop a deep understanding of what right- and stake-holders care about. Research and practice demonstrate over and again that this is a prerequisite to sustainable and inclusive urban planning.

As a community of practice working on urban nature, we can leverage technology ― the metaverse or a flipchart and marker ― to step up the work on participatory planning, scenario visioning, and further advance our shared understanding and progress toward a City in nature. The Nature Futures Framework can help us do that.

Perrine Hamel

Singapore

Thank you to colleagues in my lab and participants in the IPBES workshop on the Nature Futures Framework (November 2022) for inspiring this post. Special thanks to Shaikh Fairul Edros and Aura Istrate for their active work on the topic and for reviewing this post

Leave a Reply