Introduction

about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

What if we explored a rich storytelling approach to knowledge from science and practice? Human-scale stories. Stories with emotional resonance. Dare I say it? Even entertaining stories. Stories that connect to people who perhaps are not “experts” in whatever field, but nevertheless have a real stake in the decisions and outcomes.

There are five key elements to just about every story: plot, setting, characters, point of view, and conflict (that is, a tension that presents itself). We typically use all of these when we recount a story or event to our family and friends, at least subconsciously. (“Hey mom, I went to the corner store for milk and ran into a weird scientist planting a red maple tree. Turns out he is my Uncle Bob. I didn’t know I had an uncle. What’s up with that?”) Beyond these five elements, there are many different ways to tell a story, in various formats or styles. Mystery. Surprise. Comedy. Tragedy. Graphic. Theatre. Fiction. Direct address. Song. Folk tale. There are, as we all know, many kinds of “story”.

But we don’t use such techniques in science. Why not? Work in science and practice contains much important and interesting information for a general and policy-making public that is larger and wider than traditional scientific modes of delivery reach (e.g., journals, scholarly books, reports, case studies). Much of it lies fallow, only available to small groups of “experts”. Journalism has been one route to wider audiences, but it is limited. Science has lost its knack for communicating with the public just when we need it most.

What if we explored a rich storytelling approach to knowledge from science and practice? Human-scale stories. Stories with emotional resonance. Dare I say it? Even entertaining stories. Stories that connect to people who perhaps are not “experts” in whatever field, but nevertheless have a real stake in the decisions and outcomes, and so deserve to have access to the knowledge that supports (or does not) decision making.

Examples of storytelling approaches to science exist, but they are rare compared to the total volume of output in science. Could we take something from this approach to communicate science and practice to a wider audience?

At TNOC we have been very interested in fiction-based or art-centered storytelling about issues based in science and practice. Our recent NBS Comics project (“nature to save the world!”) is an example, and in a previous roundtable we explored visual storytelling as an evocative approach to environmental and social justice conversations. Entertaining and human-scale stories can be satisfying sources of basic knowledge and inspiration. For readers interested in more, they can also be doors through which people can pass into realms of more technical knowledge. This is the approach we take in our art exhibits as well, so that they become art[+science+practice] exhibits.

Examples of storytelling approaches to science exist, but they are rare compared to the total volume of output in science. Could we take something from this approach to communicate science and practice to a wider audience?

So, we asked a group of scientists, practitioners, and artists this: If you were to approach some aspect of a work of science or practice — perhaps your own work — as a story, what would you do? What form would you use? Would you seek out new collaborators? How would you tell the story of your work?

What could we achieve with such a novel, more “popular” approach to science communication?

It is as if we have come to believe that for a science story to be true it must sober and direct, humorless and impersonal; complicated and technical. Such an approach underestimates the general public. What if, as Ania Upstill asks in this roundtable, we stretched our imaginations beyond what we think a story of science should be, to what such a story could be?

Paul Mahony

about the writer

Paul Mahony

Paul is General Manager of Oppla, the EU Repository of Nature-based Solutions (based in the Netherlands), and Creative Director of Countryscape: part design agency, part environmental consultancy, based in the UK and Estonia. He has over 20 years’ experience in communications and knowledge exchange within the public and private sectors.

Small stories have real potential for carrying messages. Because they’re normal. Just like us.

Stories are how we understand the places in which we live, work, and play. I mean, really understand and connect to them. As people.

And as people, it’s not always the biggest and most exciting stories that grab and hold our attention. Sometimes, perhaps even most of the time, it’s the smaller, more personal, and private stories that resonate with us the most. Because we can relate to them in the context of our own lives; and because we all enjoy glimpses of other people’s lives, even the things that others might consider mundane. Everyday life is, after all, something that we all share and experience every day.

The power of ‘small stories’ is an approach that myself and colleagues have used successfully in the tourism industry. We developed what’s become known as the Sense of Place Toolkit method whereby we encouraged small, often rural businesses to tell their own stories through their marketing. To make a USP of their authenticity and relatability. To express their love of the landscape in how they communicate with customers. We piloted the idea with a small community in Lancashire, UK, and it proved highly successful (we came second in an international award to the Grand Canyon! A story in itself…). And it made me realise that small stories have real potential for carrying messages. Because they’re normal. Just like us.

What am I getting at here? Well, sometimes those of us working to “save the world from imminent environmental catastrophe” have a habit of hyperbole. Of telling the biggest stories we possibly can. Of going into battle ― and it is sometimes a battle ― with the baddest, burliest headlines that we can muster. It’s what we see in the news, right? It’s what turns people’s heads and gets their attention. It’s why Hollywood movies fill theatres. But are those big stories really what makes people stop and think? Perhaps they are too big. Too fantastic. Too remote and unrelatable to our everyday lives. Who among us are the Hollywood action heroes capable of responding? (ok, maybe you…).

So, I think we need to be telling more small stories in the environmental space too. In fact, only yesterday while the news media was ablaze with imagery of Rhodes on fire during a heatwave, I had a conversation with my dad about why his vegetable garden is looking out of season, and I think, just maybe, he nudged a little closer to accepting that the world might be changing after all. Not because Rhodes is on fire, but because his beans aren’t what they should be this year.

TL/DR: Sweat the small stuff. Put it to work. Because sometimes when your message isn’t getting through, you need to dial it down and not up.

Bram Gunther

about the writer

Bram Gunther

Bram Gunther, former Chief of Forestry, Horticulture, and Natural Resources for NYC Parks, is Co-founder of the Natural Areas Conservancy and sits on their board. A Fellow at The Nature of Cities, and a business partner at Plan it Wild, he just finished a novel about life in the age of climate change in NYC 2050.

Like any narrative that is built around the unfamiliar, communicating our story of rewilding suburban yards, campuses, commercial, and institutional spaces, is challenging.

At Plan it Wild, a sustainable landscaping company based in Westchester County, NY and Fairfield County, CT, we are disrupting the landscaping industry, elevating its value from merely the indiscriminate “mow and blow” to be “synonymous with ecological restoration”— a phrase coined by leading ecologist Doug Tallamy, who also is a Plan it Wild science board member.

Like any narrative that is built around the unfamiliar, communicating our story of rewilding suburban yards, campuses, commercial, and institutional spaces, is challenging. People are confused by the somewhat foreign concepts of adding biodiversity, native plants, new habitats, and natural growth to their backyards, fields, and patches. Consequently, our dilemma is to compellingly retell the story of landscaping in these ways:

- Style. Yards look different after a patch of lawn is turned into native habitat. They look wilder and less overtly ornamental. Rather than paint this atypical picture, a better approach could be to talk about the transformation from lawn to forest and meadow as the new normal in that mirror’s a region’s ecosystems and habitats.

- The lawn is obsolete. Not all of it. Open flat space is necessary for recreation, but a high percentage of can go native. We need to tell this story without preaching or condescension ― as if there is no choice but to do this ― but rather by its benefits; for instance, public health and helping to reduce the effects of climate changes are parts of the answer.

- The yard as bigger than just what we see. How can one yard, one campus be meaningful in a huge global movement? The appropriate depiction is to talk about the yard as an essential piece of the whole. Our partners at the Aspetuck Land Trust have called their overarching land conservation campaign the “Green Corridor” and have framed it so that every yard counts towards creating the corridor. It’s a good way to talk about rewilding the suburbs ― as a form of interconnectivity.

- Science. Although broad data on environmental benefits can be helpful in getting people to shift their lawn perspectives, it’s too abstract. A better story would include descriptive and easy to understand examples and metaphors. Plan it Wild is creating a biodiversity tool to measure the impact of rewilding in urban and suburban spaces so we can talk about the science through specific imagery and data points for an individual yard or patch of land.

- Cost. Although there are many obvious benefits of restoring nature in your backyard ― it is a moral and community-minded thing to do; it can result in more family activities, like gardening and rewilding together; it improves the beauty of your home ― rewilding is a complicated project. And when we tell potential clients how much rewilding will cost, they often suffer sticker shock, because regular lawn maintenance is so cheap. To overcome this reluctance, we need to craft a better story that portrays the real value at any price of natural habitats and the cleaner air and water that comes with restoration. And we must tell them that our goal is to create year-round green jobs for land stewards instead of one-off day labor for undocumented and unprotected workers.

Plan it Wild launched a campaign called “Less Lawn, More Life” to get people into their yards to observe their nature through the iNaturalist app. Through this program, we hope attitudes will change, and rewilding will become more commonplace and familiar. This citizen-science effort will also feed data into our biodiversity measurement tool, which in turn will yield us simple language and numbers to show the benefits, values, costs, and necessity of bringing back nature.

To make our story better, we’d find a short clear emotional but logical way to tell the story that includes all the pieces above. What do you think?

Tim Lüschen

about the writer

Tim Lüschen

Tim Lüschen is working at the intersection of deep participation and sustainability transformations. His interests lie in different ways of knowing, human-nature connection, facilitation, systemic constellations and new combinations of art and sustainability.

New collaborators are essential. We should form partnerships that have not existed before, creating a novel effect for the audience. Why not collaborate with more-than-human beings? Let them take center stage in ways and media that have yet to be explored.

One essential aspect of my work is the story of the relationship between humans and the more-than-human world. It involves highlighting our unawareness of our connection and being-as-nature, as we tend to focus so much on our separation and division, creating an illusion that we can completely dominate and control “nature”.

How can we bring more awareness and foster discussion on this topic? How can we perceive ourselves and the rest of the world as nature-culture? What kinds of stories can we tell? Hopeful stories? Warning stories? And what medium should we use? Paper, a stage, the internet, a forest, film, a podium, tape, or a crossroads? How can we effectively convey a compelling story based on scientific and philosophical ideas?

In my view, new collaborators are essential. We should form partnerships that have not existed before, creating a novel effect for the audience. Why not collaborate with more-than-human beings? Let them take center stage in ways and media that have yet to be explored. For instance, in the French documentary film “Le Chêne”, an oak tree and its inhabitants serve as the main characters over the course of a year, without any narration. It is a good example of how to incorporate the latest scientific knowledge about different living organisms, while at the same time allowing them to reveal themselves by simply BEING themselves.

Another novel approach to communication would be to focus on conflict. By illustrating the conflict of perceiving the more-than-human world as alive and autonomous entities, as their own subjects, we can address a long-standing suppression. Numerous conflicts, both conscious and unconscious, arise within ourselves when we broach this topic. Therefore, it is crucial not to depict this conflict as stagnant, but as fluid and open, with possibilities leading in various directions and opening up new vistas.

Consider the Greta and the Fridays for Future movement as an example. After seemingly being stuck for a prolonged period in the discussions about the climate crisis, with no progress being made, the silenced future generations suddenly demanded a voice in this process―naming the concrete conflict present, and the injustices included in it. With this, a shift occurred, and a new normal emerged.

However, this conflict involves many other voices that have been silenced. What if other suppressed voices begin to demand attention and lay their fingers on the other wounds that we were ignoring before? The voices of plants, animals, and the broader earth? Let them express their points of view—their sufferings, joys, and experiences.

Such storytelling has the power to stir people, connecting new brain functions and reactivating old ones. The animalistic spirit, inherent in all of us, could howl once again, and with that comes conflict. Conflict arises with those who benefit from suppressing this perpetually-present perception of the world. Conflict arises from past traumas and difficulties associated with this perception. Conflict arises regarding new decisions and how to make them.

Once again, it would be helpful to view the more-than-human beings as collaborators rather than enemies. Portray them as real, well-defined personalities, just as detailed as any main actor in a compelling story and encompassing a vast array of different characters―a world of difference within sameness, just as in our human world. Such storytelling has the potential to be more alive and resonant, connecting with the entirety of the human being, rather than solely engaging the left part of our brain. It has the capacity to evoke something within people that has not been stirred before. Let’s open up the box.

Ibrahim Wallee

about the writer

Ibrahim Wallee

Ibrahim Wallee; is a development communicator, peacebuilding specialist, and environmental activist. He is the Executive Director of Center for Sustainable Livelihood and Development (CENSLiD), based in Accra, Ghana. He is a Co-Curator for Africa and Middle East Regions for The Nature of Cities Festivals.

The people’s voice matters in validating development outcomes, be it positive or negative. Telling their story is essential and even more crucial in building trust.

In today’s contemporary world, the emergence of participatory communication, a bottom-up dialogic communication model in the development field, introduced in the 1950s by the Brazilian adult educator Paulo Freire has evolved into the preferred communication model. This communication medium is deployed in pursuing development as social change, giving voice to the people, and empowering communities sociocultural and economically. As an influential proponent of the participatory communication theory and practice, Freire’s focus on dialogical communication, emphasizing participatory, and collective processes in research, problem identification, decision-making, implementation, and evaluation of change, is instructive (Mefalopulos & Tufte, 2009). His critique of extension works (1973) and a book on liberating pedagogy (1979) emphasize a close dialectic between collective action and reflections and work towards human empowerment (ibid: 3).

The participatory communication model engenders resonance with the plight of the vulnerable, acceptability, and a broader reach of new audiences within the development ecosystem. The model appeals to social context and cultural sensitivities and enriches development outcomes by promoting ownership and communal participation. For development practitioners to demonstrate value to beneficiary communities, this model remains an inclusive and effective tool that unpacks the complexities of development discourse to bridge the knowledge gap and elicit an understanding of the value proposition in its social and practical context.

It is worth recognizing that sociocultural context matters to development practice because human identity, socialization, and cultural sensitivities, relative to language and value propositions, play an important role in gauging the effectiveness of development outcomes. Irrespective of the contentions and the problematization of the concept of development and its imperial leanings espoused by Arturo Escobar and Henry Veltmeyer, to mention a few. It is where participatory communication empowers people in its two-way dialogic medium of interactions. It allows society to establish substance and affirm a sense of ownership and value in the interaction of practitioners with beneficiary communities, leading to an appreciation of contributions to the growth of the knowledge economy and its relevance to social change and economic empowerment. The people’s voice matters in validating development outcomes, be it positive or negative. Telling their story is essential and even more crucial in building trust. Hence the need to recognize that people are voiceless not because they have nothing to say but because nobody cares to listen to them (Malikhao & Servaes, 2005: 91). This is why participation promotes listening, builds trust, and facilitates equitable exchange of ideas, knowledge, and experiences (ibid). Paulo Freire refers to this as “the right of all people to individually and collectively speak their word” (Freire, 1983: 76). He emphasizes that it is not the privilege of a few but the right of every man to do so. “No one can say a true word alone, nor say it for another prescriptively, robbing others of their word (voice)” (ibid). Freire’s postulation depicts not only the empowering but liberating nature of participatory communication and its receptive outlook towards diversity and multiplicity of views, including conflicts, to inspire efforts at addressing contemporary challenges of society.

The inclination to choose participatory communication in telling a story of development practice that reaches new audiences, far and wide, stems from the above enumerations of this dialogic communication model’s value and substance. Even more imperative is that the inherent conflicts associated with the concept of development as a practice are subjective. The diversity of thoughts and views on development discourse adds to the vortex of the complexity and challenges that require a multidisciplinary approach to proffering solutions to achieving and validating desired outcomes. It is where using collaborative channels of communication that bridge the gaps between the technical, innovative, and inspiring discourses reaches an extended audience within the public sphere. Every voice matters and deserves listening, reinforcing Freire’s insistence that dialogue is not false participation but an indispensable component of learning and knowing.

References:

Escobar, A. (1999). The Invention of Development. Current History, 98(631), 382-386.

Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc.

Malikhao, P., & Servaes, J. (2005). Participatory communication: the new paradigm? Media and Global Change: Rethinking Communication for Development, 91-103.

Mefalopulos, P., & T. T. (2009, June). Participatory Communication; A Practical Guide. World Bank Working Paper No. 170, pp. 1-50.

Veltmeyer, H., & Parpart, J. (2018). The Development Project in Theory and Practice: a review of its shifting dynamics. ResearchGate, 1-52.

Marcus Collier

about the writer

Marcus Collier

Marcus is a sustainability scientist and his research covers a wide range of human-environment interconnectivity, environmental risk and resilience, transdisciplinary methodologies and novel ecosystems.

The ideal situation would be to bring the potency and alluring qualities of traditional storytelling together with the conveying of our scientific findings. We have seen some examples, but it is still a huge area yet to be discovered, and it offers good storytellers a lifeline as well as an opportunity to expand their range and to become more central in the era of social media.

Myths and Legends | Facts and Figures

In Ireland, storytelling has had a very long tradition and also a strong social currency. For centuries, it has been the main mechanism for imparting information, though it often included an augmentation of facts for entertainment purposes. I have recently been reading stories of Irish Myths and Legends to my 8-year-old grandson. They, like such stories from many other cultures, often contain dramatic amorous convolutions, monsters and magic, and a smattering of war and decapitation―something for everybody! It is not so different from many Hollywood sci-fi fanaticise blockbusters. Interestingly, my grandson prefers to have the stories read to him over watching screen adaptations of them. He claims that he likes to “see” the action in his mind, and we often discuss some of the issues that arise from the story in question―ethical, social, and so on. However, he often stops me to fact-check something about the landscape or location, and to ask if this animal or that bird is still common. In other words, in his mind, these stories are a mixture of social and ecological facts as well as fantasy (for more on this have a look at Liam Heneghans’ excellent Beasts at Bedtime). So, it is clear to me how valuable a story is, however real or imaginary, for imparting factual knowledge. In fact, I was also amazed how I still remember the stories, having heard them read to me at the same age, I venture to suggest that everyone reading this also remembers such stories. Storytelling still has this potency as well as a currency.

Though I am an academic who originally worked in the NGO sector and before that in the Arts sector, I feel that communication of scientific or project findings is still as perplexing and as frustrating as ever. One of the main issues is the precise level at which findings should be pitched. We want to pitch just once and not spend our precious time creating several narratives for diverse communities of interest―planners, policymakers, managers, the public, diverse ages, ethnicities, abilities, and so on. Luckily, science has changed radically in recent decades. It is no longer purely science for curiosity, rather we are in the era of engaged science in a time of crises. This means that we highly value citizen participation and co-creation in identifying pathways for dealing with multi-faceted issues such as biodiversity loss, climate crisis, resilience, and becoming more nature-positive. Citizen science has the potential to change scientific investigation in the same way that citizen journalism has changed the media (for good as well as ill), and citizen science may be able to deliver the co-benefits of science better. These benefits include communicating to wider society by making scientific findings relevant as well as acceptable. The citizen-centric approach in science is also tailor-made for a new era of dramatic storytelling to enable more engagement and participation in science. We still have that childhood curiosity to fact-check fairy tales and legends.

The ideal situation would be to bring the potency and alluring qualities of traditional storytelling together with the conveying of our scientific findings. In recent years, we have seen some examples, but it is still a huge area yet to be discovered, and it offers good storytellers a lifeline as well as an opportunity to expand their range and to become more central in the era of social media and distraction.

Why stop at storytelling? All the arts have equal opportunities here―music, dance, design, and so on. If you create the right story, you can engage with a much wider audience and if my own experience is to count, people will remember the facts for a lot longer. This is how we will enable the kinds of behaviour change that will help us be more sustainable and more resilient, but as we say in Gaelic: sin scéal eile (that’s another story)!

Daniela Rizzi

about the writer

Daniela Rizzi

Architect/urban planner (Faculty of Architecture & Urbanism of the University of Sao Paulo). Holds a doctoral degree in landscape architecture and planning (Technical University of Munich). Senior expert on Nature-based Solutions and Biodiversity at ICLEI Europe (ICLEI Europe).

Despite its potential, storytelling is not widely utilized in scientific communication. However, science should not just be about cold facts and figures; it has the power to change lives, protect our environment, and shape our future. That sounds like a good story.

Imagine reading a scientific paper filled with jargon, complex terminology, and dense data charts. It can feel like deciphering a secret code! Scientific communication, as we know it, tends to be quite formal and even a bit rigid, focusing on presenting information objectively and relying on data-driven analysis. While this approach is essential within scientific circles, it often fails to captivate a wider audience or pique their interest in highly relevant societal topics. To truly engage a broader audience, we need to go beyond the dry and detached approach. We must find ways to connect with people on a personal level, appealing to their interests, emotions, and experiences. It’s about telling stories that make relevant data relatable and accessible.

Storytelling offers a powerful avenue to connect with people on an emotional and narrative level. It is a timeless art that has been used for centuries to captivate audiences and convey meaningful messages. When we hear a compelling story, we become invested in the characters, their experiences, and the journey they undertake. It evokes emotions, sparks our imagination, and leaves a lasting impact. Despite its potential, storytelling is not widely utilized in scientific communication. However, science should not just be about cold facts and figures; it has the power to change lives, protect our environment, and shape our future. So, it is extremely important to consider a storytelling approach in science communication to bridge the gap between experts and the general public. Stories also allow complex ideas and information to be conveyed in a relatable and accessible manner. By incorporating elements such as plot, setting, characters, point of view, and conflict, scientific information can be presented in a more engaging and memorable way. Scientific works can become captivating stories that grab the listener’s attention and take them on a thrilling journey.

Even if you think you can’t do storytelling, it’s just about starting. Anyone can become a storyteller. I wasn’t one, but I became one. Today, when I talk about nature-based solutions to a wider public, I instinctively try to identify the key elements that can make it a relatable and compelling topic. A personal connection to the subject matter also adds a layer of depth, as people can recognize passion immediately, and it resonates with them. Maybe this is the reason why I have gained a substantial number of followers on a professional social media platform. My posts breathe my genuine enthusiasm for nature-based solutions, capturing the hearts and minds of my audience. I share my journey, narrate the challenges I encountered, the obstacles I overcame, and the lessons I learned along the way. It’s like painting a vivid picture of the discoveries I made, unveiling the hidden secrets and unravelling the mysteries that lie beneath the surface. By infusing my story with this personal touch, I create a narrative that not only showcases expertise and achievements but also breathes personal interest and commitment. It humanises my work, making it relatable and inspiring to others who share my passion.

By adopting a storytelling approach to science communication, we can potentially achieve greater accessibility, engagement, and understanding among a wider audience. By making science feel relevant and impactful, we can capture the attention of even the most sceptical listener. This approach has the potential to unlock the valuable knowledge and insights from scientific work that often remain confined to specialised publications and limited audiences.

To approach my own investigative work as a story, I would need to identify the key elements that make it compelling. Picture this: instead of drowning readers in technical jargon, I would use language that everyone can understand. I would weave together narratives, visual aids, and real-life examples that ignite curiosity and spark imagination. It might also involve seeking out new collaborators from different disciplines or backgrounds to bring diverse perspectives and expertise.

So, let’s break free from the constraints of traditional scientific communication. Let’s embrace storytelling, engage our audience’s emotions, and make science an exciting and accessible adventure. Together, we can unravel the wonders of the natural world and inspire a lifelong curiosity about the mysteries that science seeks to uncover.

Ania Upstill

about the writer

Ania Upstill

Ania Upstill (they/them) is a queer and non-binary performer, director, theatre maker, teaching artist and clown. A graduate of the Dell’Arte International School of Physical Theatre (Professional Training Program), Ania’s recent work celebrates LGBTQIA+ artists with a focus on gender diversity.

Scientific writing often seems to assume that for something to be taken seriously, it must be dry and fact-based. The more seriously written something is, the more true it is. But what if that wasn’t the only way to go about it?

As an Applied Theater maker, in addition to the five key elements of stories pointed to above, I’m also interested in what form a story takes. Is it told live to an audience? Is it told via printed media? Is it told as an audio story or a podcast? Is it a play, or a song? Is it, perhaps, told by puppets?

I am intensely interested in this question. Despite the “Theater” in the name, in Applied Theater we don’t assume that a traditional theatrical performance is the best way to tell a story. Instead, we utilise a variety of frameworks to engage participants, from Theater of the Oppressed―where audiences step into roles to attempt to change outcomes―to Theater-in-Education pieces that use artifacts to engage young audiences, and many more. In my work as a theater maker, I have also utilised a variety of forms, from circus to music, in order to best fit the content of the story that I’m telling. For something highly emotional, music is a powerful tool. For something that requires a sense of magic or awe, circus is incredible. For something that needs to invoke a sense of curiosity, there’s nothing quite like clowning.

With stories, I believe that humans want to be moved and entertained. This might be especially true for theater, but I think that it’s true for all stories. Scientific writing often seems to assume that for something to be taken seriously, it must be dry and fact-based. The more seriously written something is, the more true it is. But what if that wasn’t the only way to go about it? As children, we learn lots of incredibly valuable information from picture books or from puppet shows about, say, the importance of brushing our teeth. I’m curious about how different forms of storytelling can be used to reach new, different audiences. What if scientific knowledge came through a poem? Or a song (like in the They Might Be Giants album Here Comes Science)? Reading Rainbow was popular for decades, and is still enjoyed by audiences. Part of the show’s success, I believe, is that instead of simply recording a child’s storybook, it used a compelling host who provided a contextual frame for each story. It’s also telling that they stopped producing new episodes in response to the many new types of media that were becoming available. If one of the most successful children’s shows was responding to the times, shouldn’t we?

I would love to see more writers exploring using different forms to tell their stories, especially around science. Facts deserve to be delivered in a compelling and interesting way so that they can really be heard. I’m interested in what could happen if we stretched our imaginations beyond what we think a story should be, to what a story can be. One of our powerful tools is form, and I challenge us all to consider which of our many exciting storytelling mediums best suit the stories we’re trying to tell.

Lindsay Campbell

about the writer

Lindsay Campbell

Lindsay K. Campbell is a research social scientist with the USDA Forest Service. Her current research explores the dynamics of urban politics, stewardship, and sustainability policymaking.

I am humbled by what I have learned from curators and artists about how to convey ideas, emotion, and complexity in a way that grabs and holds the audience.

To tell a better story about care, I work with artists and curators.

I experienced this firsthand when we were trying to communicate the importance of our Stewardship Mapping and Assessment Project (STEW-MAP) to civic groups across New York City. As researchers, we were showing up at workshops and public events with our typical 1-sheet and trying to recruit people to participate in our social science survey. But we weren’t capturing the heart and soul of why stewardship matters. And people were passing our table by.

So, we worked with the artist Carmen Bouyer, who developed a stewardship storytelling exercise. With a series of open-ended prompts, a print map, and a deck of cards of stewardship actions, we suddenly had a meaningful and easy way to interact with stewards. We asked them to share a place and way in which they helped take care of the local environment and to mark it on a map. While conceptually Carmen was asking the same questions we were, she did it in a way that was tactile, playful, and accessible. It didn’t take a 20-minute survey to get on her stewardship map, just a few moments of writing or speaking. If you were stumped for ideas or embarrassed that you didn’t think you made a contribution, you could flip through the card deck for ideas or inspiration.

We took our stewardship storytelling “on the road” with everyone from seasoned urban forestry professionals to local youth. We elicited heartfelt stories of environmental caretaking―large and small. Community clean-ups, tree planting, starting new educational NGOs, water quality testing, composting… as people added their stories to the map in real-time, they could watch the accumulation of these practices and feel a part of the community that we observe so vibrantly in our research, but that can be hard to see as a collective force.

Working with Can Sucuoglu, we incorporated stewardship storytelling as a digital map in our exhibit Who Takes Care of New York? at the Queens Museum and later as an online exhibit at The Nature of Cities. Our goal with each of these stewardship storytelling efforts is to make care and connection to place more visible and valued.

In addition to being inspired by the stewards themselves, I take my inspiration from visionaries like artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles whose Manifesto for Maintenance Art makes clear the importance of caretaking to the functioning of our world. Overall, I am humbled by what I have learned from curators and artists about how to convey ideas, emotion, and complexity in a way that grabs and holds the audience. These are often afterthoughts in science; we are not taught to be effective communicators.

Nic Bennett

about the writer

Nic Bennett

Nic Bennett (they/them) researches power, ideology, and belonging in science communication at The University of Texas as a doctoral candidate of the Stan Richards School of Advertising and Public Relations. They engage arts- and science-based research and practice to critique, disrupt, and reimagine science communication spaces. Alongside scientists, artists, activists, and community members, they hope to expand the circle of human concern in science communication and STEM.

There is already a lot of amazing fanfiction about science. People are literally writing themselves into science stories. Recognition by powerful institutions of these science story remixes would increase belonging in these spaces. Fanfiction about science, by people who don’t usually see themselves in science, has the potential to disrupt usual knowledge and power relations.

A Fanfiction of Belonging, for Science

Can thinking like a fanfiction writer help science be a place of belonging?

Fanfiction is stories based on previously existing works. It’s anything that you make to celebrate a piece of culture you love. And it’s not just making your favorite Star Trek characters kiss (although that is awesome), it is a powerful form of participatory culture.

The popular imagination usually pins fanfiction as “lowbrow”, but “classics” like the Aeneid, Romeo and Juliet, and Lord of the Flies are all examples of fanfiction. We must also think critically about what we call “lowbrow”. This elitism is usually lobbed at marginalized groups to portray their culturally relevant creative expressions as “less than”.

Is science a fandom? And, if so, does it have fanfiction?

In this short post, I want to argue that thinking about science’s fanfictions is a useful way to think about how to transform science’s culture into one of belonging.

Science is a part of culture. We tend to think of science as a separate, rational endeavor, but it is done by humans and is made of rhetorical and narrative moves. In the same vein, science communication can be considered one of the many aspects of popular culture, rather than separate from it. This means looking at science communication as a process of making meaning, rather than informational transfer or even a dialogue.

Using this lens, we might notice that most mainstream science communication kind of looks the same: journalistic, cheerlead-y, and very white. Narratives of scientific certainty have been historically (and currently) used as a tool for othering (e.g., IQ tests, scientific racism, race-based medicine). A fanfiction of science reimagines that.

Just as fans creatively express their Kirk/Spock romances and make Star Trek stories their own, fanfiction for science is an act of worldmaking. For example, take Andy Weir’s science fiction novels and films (e.g., The Martian, Hail Mary). His works feature a lone, male hero who sciences himself out of a series of tricky situations—in space. These novels are loads of fun, but only consuming myths of the lone male science genius impoverish our worldmaking. Mainstream science storytelling is also culturally narrow, privileging dominant groups and ways of knowing (e.g., Western, abled, cis, affluent, white, heteronormative, male). It tells a single story from the dominant group’s perspective. Fanfiction may be a way to invite a plurality.

Fanfiction, as an act of science storytelling, might disrupt this. When queer audiences don’t see themselves in a franchise they love, they write themselves in. Fanfiction about science, by people who don’t usually see themselves in science, has the potential to disrupt usual knowledge and power relations.

There is already a lot of amazing fanfiction about science. People are literally writing themselves into science stories. Recognition by powerful institutions of these science story remixes would increase belonging in these spaces. If fandom is an expression of the collective self, how can our narratives of science serve as imaginal and transformational tools?

Opening up and considering science as culture, as more like a fandom than an elite institution, could widen the circle of human concern. We must push hard on the boundaries of what we include as science storytelling. Fandom allows for both individual expression and communal belonging, and a radically re-imagined science fandom has immense generative power. Let’s write ourselves in.

Sarah Ema Friedland

about the writer

Sarah Ema Friedland

Sarah Ema Friedland is an NYC based film and media artist and educator. She is currently working on a feature documentary titled Lyd, which she is co-directing with Rami Younis, and which was selected to pitch at the DocCorner Market at the Cannes Film Festival and Days of Cinema in Ramallah. Friedland is a member of the Meerkat Media Collective and the Director of the MDOCS Storyteller’s Institute at Skidmore College where she is also a Teaching Professor in the MDOCS Program.

Reality is much more interesting than oversimplified, packaged, and commodified stories. The stories we tell about reality, including and especially scientific reality, cannot be contained by formulaic storytelling. Instead, nuance and difference should inform the way we tell stories.

As someone who makes and teaches non-fiction filmmaking and runs a residency for non-fiction storytellers, storytelling makes up the joys and frustrations of my daily grind. I love a good story, I love being taken on a journey and hearing/seeing/reading powerful descriptions of places and people. However, I am also annoyingly aware of the ways constructed stories can trap and oversimplify reality.

As a film student, I learned that good storytelling follows a three-act structure ― beginning middle, and end ― with rising action, stakes, conflict, and resolution. Joseph Cambell’s “Hero’s Journey” was dragged out so often as evidence that this is the way that stories have always been told and therefore the best and only way to tell stories, that even the scholar of mythology himself would have rolled over in his grave at the ways his life’s work has been oversimplified to package and commodify storytelling. Reality is much more interesting than the Hero’s Journey, and the stories we tell about reality, including and especially scientific reality, cannot be contained by formulaic storytelling. Instead, nuance and difference should inform the way we tell stories.

The science fiction/ fantasy writer Ursula K. Le Guin offers another way of shaping stories in her influential essay “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction”. She bases her preferred shape for a story, the carrier bag, on what anthropologists have cited as the first tool: not a weapon, but a bag, used to gather, keep and hold dear items of both necessity and joy. Narratively, this bag is a bottomless vessel for the valuing of experiences, ways of being, and conceptions of time.

Scientific Anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing applies Le Guin’s theories to science, “Science in the broadest sense of the term refers to knowledge that we can collect, collate and put in our carrier bag. And this broad sense of knowledge creation involves all the kinds of observation and noticing that we could do. For our times, facing the climate crisis, the extinction crisis, all of those other environmental catastrophes that surround us, we’re going to need a lot of kinds of science.”

And we are also going to need lots of different kinds of storytelling that reflect science and scientists with rigor and complication. Science and non-fiction storytelling center observation and allow us to see differences, but the most dominant forms of storytelling tend to act as a strainer of those observations, sifting out the hard-to-swallow, but juicy lumps of life and leaving behind a homogenized liquid that can be easily digested.

What is the danger in this? If we allow singular conceptions of what storytelling should be to sausage-factory-afy science and make uncomplicated heroes out of scientists, then we may jeopardize the work itself. If conflict is accentuated for a story’s sake, the importance of careful and slow investigation may be minimized for fear of it being perceived as boring storytelling. Human heroes may be prioritized, leaving behind teams of people who collaborate, and further sidelining the non-human lifeforms that should be at the center of scientific inquiry. And the importance of failure might be shoved aside in order to reach a nicely tied-up resolution.

Fascism is resurgent, the climate is in crisis, and economic exploitation is reaching new heights. To organize for a more equitable and livable planet, we need to envision it in all its complexity and in all its forms. If we do not make space in science and other all disciplines for storytelling that centers the collective in addition to the individual, collaboration and compromise in addition to conflict, and journeys that do not only march forward in time toward a neatly tied-up resolution, facing these stakes will be a lonely, rigid, divisive and devastating journey indeed.

David Bunn

about the writer

David Bunn

David Bunn is an interdisciplinary South African scientist and public intellectual. He joined UBC very recently from a position as a senior research scientist in the Natural Resource Ecology Lab at Colorado State University. Before that, he was a senior professor and head of school at South Africa’s largest university, and served in the second generation of South Africa’s post-apartheid government, helping to frame new national policies for arts and tourism funding and the archiving of indigenous knowledge.

A truly social-ecological form of science will be able to combine the insights of data and of stories. As climate change forces species and populations to seek out new habitats, urbanizing populations on the edge of conservation zones, whether in Kenya, Brazil, or Nepal will increasingly seek out occult explanations for ecological phenomena..

These Data, This Life: Ecological Science and Evidence of Stories

Science would like to use stories to better communicate with broader audiences. Unfortunately, with some singular exceptions, scientists are seldom very good at storytelling. Typically, when stories are deployed, they are frequently only illustrative and seldom advanced as a form of evidence. The world of stories, to put it another way, rarely impinges on the domain of data.

The problem is exemplified in my most recent research. I am currently directing a NASA-funded project looking at changes in land cover and animal habitat over 30 years in and around South Africa’s iconic Kruger National Park. We make extensive use of remotely sensed vegetation data, from the workhorse Landsat satellite to NASA’s new GEDI LiDar instrument. Significantly, we also have to take into account the rapidly urbanizing borders of Kruger National Park: over 2 million people live within 30 kilometers of Kruger’s western fence, with 40% unemployment. We are attempting to understand both social and ecological edge effects in this system; increasingly, this has led us to the evidence of stories.

So, bear with me. I’ll tell you a brief story.

In an early precursor to our current project, I was leading a study on human-animal conflict on the Kruger National Park boundaries. Our data were derived from camera trap analyses of lion occupancy, but we also did a series of oral history interviews. One main informant was Charlie Nkuna, an African field ranger who had lived and worked in Kruger Park for 50 years. He told me this story:

One day in 1973, the family discovered that their eldest daughter Senana had disappeared. (This was not in itself unusual: many kids her age would become bored with life in the conservation zone and run away to relatives in the neighboring urban areas to the west.) The next evening, there was a lion attack on a cattle enclosure, but the herders managed to defend themselves and the lion was wounded. Villagers asked Charlie, as the senior field ranger, to track the lion down. Following a blood spoor through the dewy grass the next morning, he came upon a sight no parent should ever have to confront: the head of his missing daughter, who had been silently dragged away and eaten some days before. Charlie and his family had lived in the Kruger Park for decades. They had walked everywhere unarmed and never had any problems with lions before. I asked him why he thought this sudden horror had occurred. His answer changed the way I understand the role of evidence in social-ecological systems thinking.

“The lion . . .,” he began, and then paused. “The lion,” he continued, looking closely at me, “was sent.”

In my scientific work, it is not so much stories that are important; rather, it is what is technically termed narration. In the act of telling, and in the pause, Charlie was judging his audience and switching to another form of explanation: the language of the occult. He knew of my interest in shifting carnivore habitat and range. However, he also clearly felt the need, in that moment, to turn the focus to the complex social dimensions of these changes. For that, he needed a different kind of language that referenced the uncanny, and that required a different kind of trust from his audience, one that he assessed briefly in the pause in his narration.

In the 1970s, Charlie recalled, a war in Mozambique produced a flood of refugees and increasing poaching from the growing urban population to the west. He himself had been very effective in arresting poachers. So, in one sense, the lions were changing their behaviour in response to increasing human encroachment. Yet perhaps, he suggested, these were not really lions at all but sorcerers from neighboring villages who had changed themselves into lions to enact revenge on him for his past policing successes. Newly urban attitudes to wealth accumulation and the waning of customary authority in the bordering towns produced a form of social rupture from which this malevolent carnivore emerged.

Stories about uncanny animals out of place should be considered as data. Narratives about lions moving out of Kruger, or leopards in the northern suburbs of Mumbai, are evidence of the way many urbanizing populations explain ecological phenomena like edge effects or fragmentation. In the manner of their telling, however, they also speak eloquently about shifting consumptive patterns in emerging secondary cities. A truly social-ecological form of science will be able to combine the insights of data and of stories. As climate change forces species and populations to seek out new habitats, urbanizing populations on the edge of conservation zones, whether in Kenya, Brazil, or Nepal will increasingly seek out occult explanations for ecological phenomena.

As scientists, we have time-honoured ways of collecting data about species and climate change: we can catalogue edge effects in fragmented forests that bring benefits to certain guilds and disaster to others, for instance, or the phenological shifts for which migrating caribou herds are now unprepared. Ideally, though, when considering these phenomena from the perspective of social and ecological explanation combined, the object of analysis itself will become something different. When communities speak about the declining salmon population and increasingly negative encounters with grizzly bears, they are speaking about a ten-thousand-year history of human-mediated systems in which other beings are ancestors and kin. Stories about these beings also reveal changes in commodity culture, gender dynamics, property relations, and the migration of local youth to regional cities.

These stories have great potential, and they hold the key to more convivial forms of local conservation management. In the manner of their telling, they are all scientifically insightful tales.

Pippin Anderson

about the writer

Pippin Anderson

Pippin Anderson, a lecturer at the University of Cape Town, is an African urban ecologist who enjoys the untidiness of cities where society and nature must thrive together. FULL BIO

We need to have an excellent plot, believable or at least striking characters, conflict (ok, no shortage of that in science), and (perhaps most relevant) resolution that gives hope, direction, and instruction.

I agree stories bring in magic that is missing in science reporting

I was a young graduate student and attending my first conference (it was the annual meeting of the South African Association of Botanists, I think). The last presentation in the session had been by a professor who was well known to me from my own undergraduate days, and it was just one of those presentations that “pops”. This professor had been an excellent lecturer, and a firm favourite with every class, which I had always put down to his colossal intellect. I was in the bathrooms just after the presentation and overheard some women talking outside my stall: “Eish, that Prof Bond, he always tells a lekker* story. I could listen to him all day.”

I was dumbstruck. That was his trick — he was a storyteller! It had never occurred to me but the magic he was weaving was stories. He was managing to take fire ecology, evolutionary theory, or reproductive ecology, and weave in a protagonist, a challenge, disappointment, and resolution, all in a manner that was so cunning and skilled that we never even noticed. This was the first time it occurred to me that good science is even better when packaged in a format that draws the reader effortlessly along.

I think we do tell stories

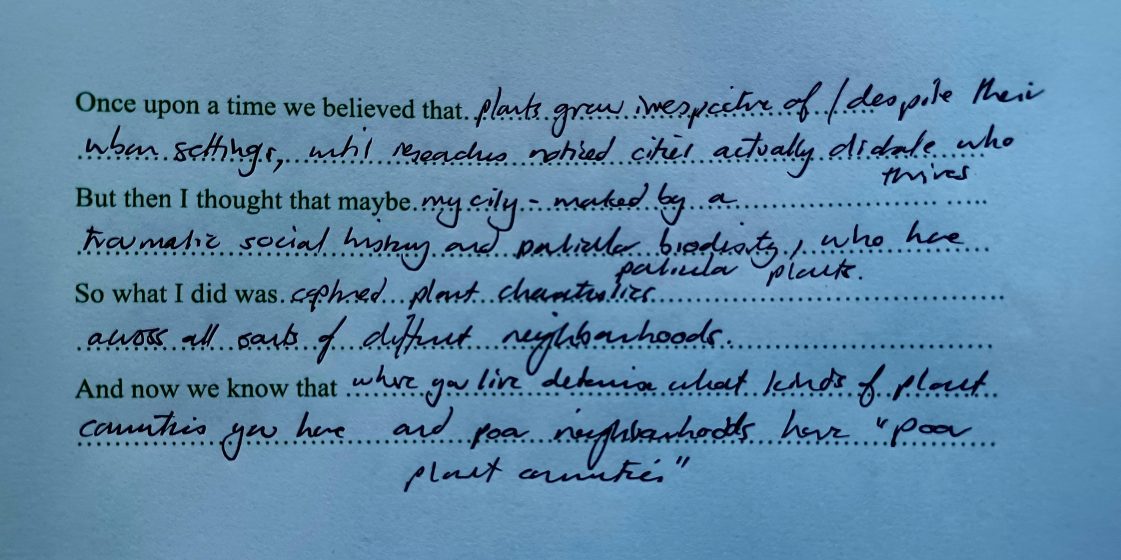

Later, while still a graduate student (it seemed to go on for years), I got a job with University of Cape Town’s Writing Centre. After serving time at the front of house, I moved to focus on postgraduate writing. I was introduced to the “Once upon a time …” exercise, used to guide postgraduate writers in preparing their papers or thesis chapters. Here it was Professors Arlene Archer and Lucia Thesen (perhaps the fairy godmothers of my own story) who reminded me that science is best presented as a story. They made me aware of the relationship we have with our readers and the responsibility of fulfilling promises and expectations in the often-opaque writer-reader contract. They introduced me to this exercise to use with postgraduate students and it is one I have pulled out every single year since then (see the image).

But are we really fulfilling the story element? Are we enthralling our readers, making them come back for more, and getting our final point to a wider audience?

But we tell them badly

The “Once upon a time …” exercise is a good one and a useful reminder of the expectation of scientific writing. But we are falling short in our story-telling abilities (responsibilities?). While we are told that a good story has plot, characters, conflict, and resolution, evidently there must be more than this to really draw in one’s audience. We need to have an excellent plot, believable or at least striking characters, conflict (ok, no shortage of that in science), and (perhaps most relevant) resolution that gives hope, direction, and instruction.

Indeed, in science writing, we are often told not to provide resolution, but to keep an open-end to allow for a natural point of departure for the next paper. We foster a soap-opera culture, where sometimes it feels the story will never end.

Good stories are well written. Heaven knows we are all familiar with a poorly told story. Of course, the apprenticeship lies in reading good stories. Humbling ourselves in acknowledging that just the science is not enough. And perhaps, finding a sidekick, a true storyteller, to assist us in our quest in turning our science into a good story. Or perhaps (better still) to actively assume the role of a subordinate character in our own stories and guide the hero, the storyteller, in the quest of turning our science into gripping and compelling stories.

Just as we assign roles to our characters, so too must we assign storyteller and story-listener roles

And of course, relevant to any good story, is who gets to tell it. Who has license to tell this story? We all know that every telling of a story will differ. Sometimes ever so slightly and sometimes by vast leaps of faith. It is important to ensure that there are lots of stories and lots of voices and that we watch out for whose story is loudest and be sure to hold our heads at just the right angle to hear the quiet stories. The stories whispered to us from the corner of the room. From across the crowd. Every good story is matched by true listening. If you can’t get the story, there is as much glory in being a true listener.

*nice, good, fantastic

Kirsten Schwarz

about the writer

Kirsten Schwarz

Kirsten Schwarz is an urban ecologist working at the interface of environment, equity, and health. Her research focuses on environmental hazards and amenities in cities and how their distribution impacts minoritized communities. Her work on lead contaminated soils documents how biogeophysical and social variables relate to the spatial patterning of soil lead.

For me, the most compelling science stories are the ones that share the humanity of the work, the humanity of those doing the work, the humanity of those impacted by the work (for good or bad), the aspects that connect us, the emotions.

A More Compassionate Science Can Bring Us Better Storytelling

The person that taught me the most about science and the importance of storytelling wasn’t a scientist, but a human that dedicated his life to compassion, David Henry Breaux. He stood on a street corner in Davis, CA asking people that passed by to reflect on the concept of compassion and share their personal definition. At the time of his murder, he had been doing that work for almost 14 years. Many came to David to extract information, to find answers. But David didn’t provide answers, he listened, deeply and empathetically. And he demonstrated with that deep listening you likely already held the answers if you were still enough to hear them. And, through that deep listening, he also showed us that we have a lot in common with one another if we’re willing to slow down, reflect, be vulnerable, and share our stories.

At the time I met David, I was a postdoc at UC Davis. As I reflected on my thoughts on compassion, I realized that in my experience of science, compassion was not valued in a meaningful way. It wasn’t centered in the process of doing science, it wasn’t considered in the process of sharing science, and it wasn’t a requirement for advancing one’s career. David helped me see that if I was going to continue with a career in academia, I was going to have to center compassion not only in my life, but also in my science.

Stories help us do just that. We need stories to share our science because stories connect us. Science may help us better understand our world, but stories help us empathize, they connect us to our world. We need stories to make our science more compassionate, inclusive, and impactful. We need stories so we can more easily connect our science, and the people doing science, to the human experience.

For me, the most compelling science stories are the ones that share the humanity of the work, the humanity of those doing the work, the humanity of those impacted by the work (for good or bad), the aspects that connect us, the emotions. Science is sometimes described as a systematic approach to answering a question. That’s often not a very exciting story. But in practice, science is a messy wandering adventure that often leads to more questions than answers, the entire process guided by perfectly flawed humans. It’s the parts we don’t often share that make great stories.

Stories are also our legacy. Thousands of people have a story of David. His story didn’t end when his life ended. His work continues, more important and needed than ever. I’ve thought a lot about my definition of compassion since David was taken from us. I think it’s creating the conditions in your life to see more clearly, to slow down, to reconnect to the stillness and compassion in your heart. It’s an active practice, it won’t always be perfect, but it will always be there. And it’s part of everything, including science. Centering compassion in our science makes sharing our stories a natural extension of the work that we do, central to our mission as scientists. And as humans.

Steward Pickett

about the writer

Steward Pickett

Steward Pickett is a Distinguished Senior Scientist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, New York. His research focuses on the ecological structure of urban areas and the temporal dynamics of vegetation.

What keeps coming to mind are powerful moments of noticing. Perhaps that is because I believe science to be, at its heart, a particularly deep and careful way of noticing the world―sometimes even what is hidden behind the surface of the world.

Future Poets: Please Pay Attention

I am convinced that scientists need to tell better stories. But I have struggled to settle my mind on an example for this roundtable on something from my own work that invites a story. Instead, what keeps coming to mind are powerful moments of noticing. Perhaps that is because I believe science to be, at its heart, a particularly deep and careful way of noticing the world―sometimes even what is hidden behind the surface of the world.

Recently, I read an interview of the poet Abram Van Engen by Tish Harrison Warren in the New York Times (16 July, 2023). Here’s a line from Van Engen that connects my feeling of science as deep noticing with attention in poetry:

“I think of poetry as the art of attention. It’s the ability to pay attention to the world and produce for the world the name of something that must be known.”

The triad sounds loudly: attention; urgent knowledge; producing. This chord could be a part of some great symphony of science as well as a harmonious representation of poetry.

I am perhaps cheating in thinking about poetry here, rather than a true narrative story. Of course, some poetry―epics come to mind―are as much stories as anything else. But how many (and indeed how) do poems engage all the five elements of story that the prompt lists? Depending on the poem in question, one or more of the elements may exist. But without trying to analyze what narrative elements might exist in it, here’s the piece of my writing, undated but more than a decade old, that kept coming to mind as something outside the usual formulation of science that still somehow emerged from understanding within science:

Spring: To a Poet of the Future

Spring came this year

with a violence

worthy of Stravinsky’s rites.

Liner notes once said

winter was replaced so suddenly

in the Russian taiga

that the music was hardly surprising.Here, the green rose hard

from the insistently moistened ground.

Rain cold and constant

fed a fierce flowering:

Spent petals piled in deep drifts;

Pollen dusting any surface

dark enough to show it

and tinting windshields

yellow.Is this the deconstructed spring?

Rain, temperature, and length of day

reassembled in some new way

ordered by a change in climate?

A new rhythm

overlapping beats

unexpected fierceness.Future poets,

please pay attention.

Let us know.

Are centuries of metaphors

of soft temperate springs

just so many discarded petals

piled up like debris

no longer decipherable as flowers?

Well, there you have it. Something to say about science, in a way that is not science. Maybe the start of a story rather than a story.

Another quote from the Van Engen interview: “Poetry is much more about undergoing something rather than understanding something.”

How do we turn things from science―understanding―into things like stories and poems that help people undergo something in their relationship to the worlds of nature in cities or elsewhere?

Alice Reil

about the writer

Alice Reil

Alice Reil (she/her) is an urban geographer who strives to bring more biodiverse, urban nature into public spaces. She led the biodiversity and nature-based solutions team at ICLEI Europe, a global city network, and now works at the City of Munich’s green space planning department.

If many of us would share our personal stories and emotional connections to our natural surroundings with our neighbours, would we all be more motivated to protect them even more? I’m now visualising little printed stories scattered across communities, which enable neighbours or passers-by to read how a particular tree or green space is meaningful to fellow citizens.

I just started a new job in which I am tasked with coordinating the local implementation of urban nature interventions through a European Union-funded project. This project aims to generate more scientific evidence as well as practical experience around inclusive and just access to ecological spaces for all in cities. At the same time, these interventions should help reduce pollution and promote biodiversity. On the one hand, this new role puts me at the receiving end of someone else’s―the project authors’―vision and narrative. On the other hand, it is my responsibility to create and adapt the reasoning for and activities of the project for local audiences. In other words, it is about the story I want to tell.

Over the past weeks, I have been asking myself: How can I translate 200+ pages of project description into a tangible narrative for myself, but also for those that we as the city department want to reach? How can we detach ourselves from keywords and turn our vision and activities into a story, which mobilises citizens to renature their neighbourhoods together with us?

I do not have the answer, I just have ideas. And I also recognise my limitations, as my education and work experience has always been tied to the written word. I would certainly seek collaborators from visual, art, or play-based backgrounds as well as “living experts” from those that we are trying to reach through the project, i.e., kids and youth as well as elderly citizens. I also recognise that not all of these are homogenous groups, yet we would try to reach and tailor our interventions to their needs as much as possible.

For neighbours and (aspiring) history buffs it might be interesting to connect nature interventions with local history, both that of the neighbourhood as well as personal connections to the community. I take some inspiration from the Melbourne Urban Forest project, which mapped all city trees, and gave them an email address―and the trees promptly not only received maintenance requests but also love letters and personal anecdotes. The City of Glasgow, together with regional partners, was recently inspired by this Australian approach. The team created “Every Tree Tells A Story” and provides educational material and social media channels for Glaswegians to share their love of trees. If many of us would share our personal stories and emotional connections to our natural surroundings with our neighbours, would we all be more motivated to protect them even more? I’m now visualising little printed stories scattered across communities, which enable neighbours or passers-by to read how a particular tree or green space is meaningful to fellow citizens.

Urban nature helps create and design public spaces. Often enough, though, art and untamed, wild nature are neglected, yet very organic elements in creating aesthetic, welcoming spaces. There is a growing number of cities that have street art walks. (If you’re ever in Ghent, Belgium, make sure to take a stroll of the open-air gallery of its many murals!) How could we combine nature and urban art in our public spaces and for sure thrill youth, kids, and art-loving residents? I have experienced art walks and always found them especially memorable such as the Rehberger Way in the southwest of Germany. I also know of artists who use natural materials to make sculptures of varying sizes. Yet this “ecological art” is often set in or against the backdrop of landscapes, and I haven’t yet seen good examples that really weave art and nature together in an (often confined) urban setting and that tell stories linked to the importance of biodiversity, for instance. Whilst I continue my search, there is a growing body of comics showcasing the state of nature as well as current challenges and how we are or could be solving them. You might have already come across the nature-based solutions comics curated by The Nature of Cities itself together with the EU-funded project NetworkNature.

Whilst these are just ideas, we certainly need different approaches to enthuse all about nature―or at least about the need to protect and promote nature. Just recently, I came across the term “plant blindness”, which describes the inability to see or notice the plants in one’s own environment. In turn, this makes it very difficult for humankind to realise the importance plants and the natural environment in general play for us and our planet. On a recent trip to the local art exhibition “Flower Power” on the role of flowers in art and culture, I saw Tracey Bush’s work called “Nine Wild Plants”: she uses collages of famous brands to depict local plant species. She wants to raise awareness that the average Western citizen knows many more brand names than they know local plants.

Perhaps we should take a break from our (project) work occasionally and go on a good, old (or GPS-supported geocaching) treasure hunt of plants and other living things and use the funny and surprising anecdotes of those plants and our experience along the way to reconsider how we approach our work. Next onto the groundwork in neighbourhoods and cities, we should strive to design projects which create scientific evidence, but also inspire everyday action―or at least awareness, and create space for playful, artistic interventions. For this, we need to engage with fellow artists and work with funding bodies to allow for better, more convincing, and fun stories of and with nature.

Skylar R. Bayer, Evelyn Valdez-Ward, Priya Shukla, and Bethann Garramon Merkle

about the writer

Skylar R. Bayer

Skylar Bayer is a marine ecologist and science communicator. Currently a marine habitat resource specialist in the NOAA Fisheries Alaska Regional Office, she received her PhD from the University of Maine’s School of Marine Sciences for research on the sex lives of scallops and is a producer for the Story Collider.

about the writer

Evelyn Valdez-Ward

Dra. Evelyn Valdez-Ward (ella/she) is a Mexican Ford Foundation Predoctoral and Switzer Foundation Fellow. Her research focuses on marginalized scientists’ use of science communication and policy for social justice. She co-founded the ReclaimingSTEM Institute, addressing the need for inclusive science communication spaces.

about the writer

Priya Shukla

Priya is a PhD candidate in Ecology at UC Davis and Science Engagement Specialist with the California Ocean Science Trust. Her research explores the effects of climate change on shellfish aquaculture in California and she is an active science communicator who is deeply invested in improving the accessibility of marine science.

about the writer

Bethann Garramon Merkle

Bethann Garramon Merkle, MFA, is a Professor of Practice at the University of Wyoming, where she is the founding director of the UW Science Communication Initiative. She also co-founded the Ecological Society of America’s Communication & Engagement Section.

Despite science’s emphasis on analytical thinking, storytelling remains compelling, memorable, and easy to understand and relate to when personal or engaging characters are involved.

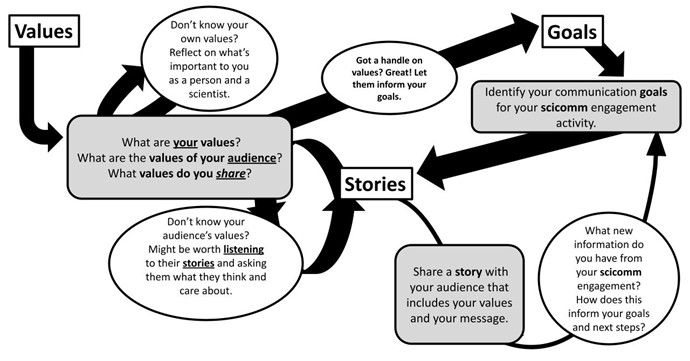

Sharing Science Through Shared Values, Goals, and Stories

Effective science communication relies on understanding the values of the people we aim to engage with. By identifying shared values, we can communicate effectively using storytelling to achieve our science communication goals. Acknowledging our own goals, informed by our values, helps us recognize the importance of understanding others’ values as well.

Respecting each other’s values is crucial because a mismatch of values can lead to information being disregarded, misinterpreted, or poorly received. This is particularly significant in ethical science communication, where our goals include co-produced science and ensuring that study results are understood and applied by those who can benefit from them.

To communicate effectively, it is essential to build relationships and recognize the value of diverse perspectives and knowledge. Science has a long history of extracting information and tangible resources from people, especially historically marginalized communities. To communicate effectively, it is critical to take a step back and build relationships that recognize everyone has valuable perspectives and knowledge. Thus, as communicators, we cannot simply enter communities and expect our information to be readily received or their knowledge to be readily shared with us. Engaging in activities such as round table discussions, consensus processes, and community events facilitates knowledge-sharing from multiple viewpoints. These interactions should prioritize listening, respecting, and valuing others’ perspectives to establish mutual trust.

As relationships develop and we understand the values of the people we engage with, we can reflect on our own values and seek out areas of overlap. This process requires revisiting our communication goals, which may evolve as we connect with different topics and address people’s concerns and priorities. This approach, known as “backwards design,” starts with shared goals and values and guides the development and implementation of effective communication strategies.

Storytelling is a very powerful tool to achieve many different communication goals. Despite science’s emphasis on analytical thinking, storytelling remains compelling, memorable, and easy to understand and relate to when personal or engaging characters are involved. Importantly, stories also embody shared values, making them an effective means of conveying key messages and reinforcing connections.

Crafting a resonant story begins by considering the goals derived from shared values. Sharing a personal story that holds significance to the communicator can foster a connection with those listening or engaging to the story. Identifying the main characters and describing the conflict and climax of the story further engage them. Exploring the consequences of the conflict reinforces the stakes of the story.

Once the story framework is outlined, drafting and practicing the story with others is necessary. Candidly describing emotions, internal thoughts, and the setting allows listeners to fully immerse themselves in the narrative. Testing the story with others, seeking their feedback, and noting their reactions helps refine the story for maximum impact. Iterative drafting and practicing stages are necessary for this process.

Ultimately, science communication can be significantly enhanced by leveraging the power of storytelling and understanding shared values. By employing a thoughtful approach and aligning goals with the intended audience, science communicators can foster engagement and create meaningful connections that drive positive change.

For a more comprehensive understanding of the tools, worksheets, and detailed steps involved in this framework, we invite readers to explore our published, peer-reviewed, open-access paper titled “Sharing science through shared values, goals, and stories: an evidence-based approach to making science matter”. The paper provides additional resources, examples, and step-by-step guidance to aid in applying this approach effectively.

Tommy Cheemou Yang

about the writer

Tommy Cheemou Yang

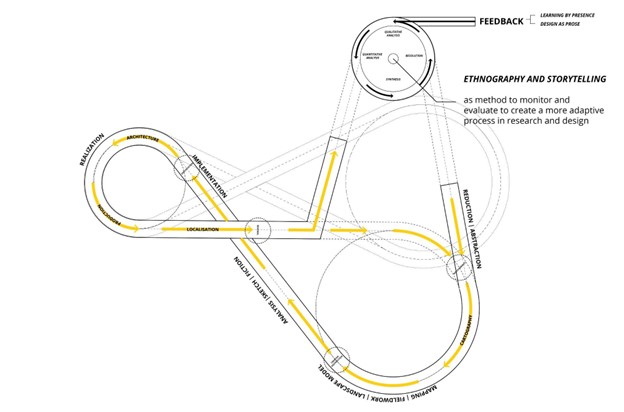

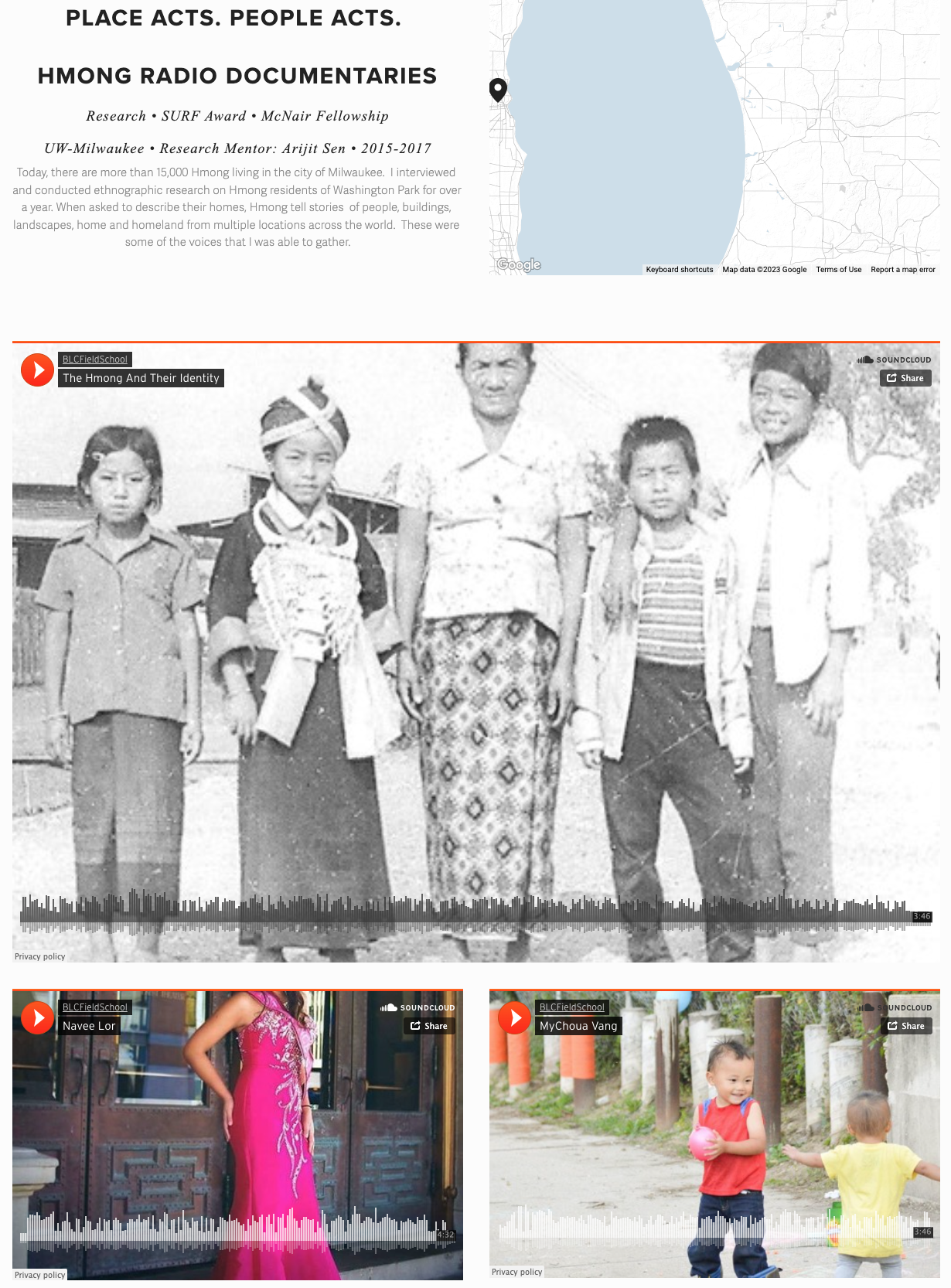

Tommy Cheemou Yang is an indigenous Hmong designer, researcher, and educator focused on insurgent urban and architectural transformations, utilizing inter-disciplinary methods such as fieldwork, oral/public history, and radical mapping. His current work challenges architectural and urban design epistemologies, cultivating conversations on identity, social action, resiliency, and insurgent placemaking.

Storytelling asks us to see that change does not come from the expert but from the mundane acts that cascade into large movements creating change.