The way in which we imagine and understand cities and define their boundaries influences how we think about governing the city, and planning adaptation and resilience strategies, which become increasingly important in the era of the climate crisis.

“…they do not belong to our neighbourhood and are located outside the administrative jurisdiction of Bangalore; hence we do not work on those lakes…” This was the comment made by a representative belonging to a prominent lake conservation group in the city, presenting a focused definition of a city as a territorially bound space, limited to its administrative (municipal) boundaries. This statement reflects a widespread point of view, raising numerous questions regarding how residents of fast-growing cities of the global South ― where de facto boundaries regularly outpace de jure boundaries ― view their cities, whether as discrete units with sharply defined boundaries or as interconnected systems that connect the wider landscape and region within which the city is embedded.

This may seem like a purely academic question, but it goes well beyond such a limiting focus. The way in which we imagine and understand cities and define their boundaries influences how we think about governing the city and planning adaptation and resilience strategies, which become increasingly important in the era of the climate crisis. Cities in the global South are growing exponentially, much faster than the present governance arrangements and infrastructure are able to adapt. For India, in particular, cities are crucial as they hold one-third of the country’s population and contribute to nearly two-thirds of India’s economic output. Thus, understanding urban boundaries is critical to planning and preparing for climate shocks.

Despite many years of work on ideas of resilient, smart, and sustainable cities, we have been caught unprepared for what the Anthropocene has wrought. Beginning with the pandemic, the 2020s have shown us that global environmental change is not a distant future threat, but something that is taking place in the here and now, impacting our daily lives and ways of living. The UN Habitat Report 2022 indicates flooding as the most common risk to urban ecosystems. An increase in the intensity of rainfall, coupled with the concretization of cities and inadequate planning, has led to flooding in nearly every major city across the globe. On July 10th, 2023, the Indian capital city of Delhi was in the news for receiving 153 mm in 24 hours (15% of the total monsoon rainfall of the city).

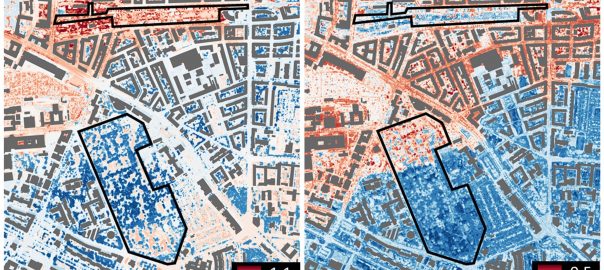

This increase in the intensity of rainfall holds true for multiple other cities, both in India and elsewhere. Bangalore received 132 mm of rainfall on 5 September 2022 accounting for about 10% of the total seasonal rainfall of the city. This led to flooding of low-lying areas and localities which were built on lakebeds as shown in Figure 1. The State government started removing encroachments and demolishing structures built on lakes and stormwater drains. Yet, little regard was given to landowners who purchased their property in good faith without knowing that they were built on lake land, while the slips in policy and governance that allowed such widescale violations to take place, often in collusion with builders and land sharks, have not been addressed. Cities like Bangalore have focused almost myopically on economic development, without consideration of the impacts that can arise when city planners and builders ignore the importance of the city as an interconnected ecosystem, embedded in the topology of the surrounding landscape and linked to regional watersheds. This goes against the principles of resilience thinking, which focuses on the need for complex adaptive thinking and managing connectivity for building the resilience of a system.

Multiple criteria have been used to define a city, leading to numerous definitions. Though there is an attempt to develop a standard definition by various international agencies, there are limitations to this standard definition being applied across regions. Economic theories seem to take precedence here, leading to many cities being defined by criteria such as population density, economic development (GDP), and access to infrastructure. These approaches seek to define a city as the spatial production of an agglomeration — but they ignore the spatial ecological and environmental relationships between the city and the larger region within which it is embedded. Even with these criteria, it is not easy to find globally consistent definitions of cities. Different countries use a range of terms such as city, metropolitan area, and urban agglomeration, by combining various definitions.

As an initial exploration, we asked residents of Bangalore a simple question ― “What is a city?” We spoke to 25 opportunistically selected residents of Bangalore: men and women, from varied socio-economic backgrounds (doctors, students, researchers, IT employees, and local business owners), living in different parts of the city, peri-urban, and rural areas. We asked each person to define a city, and also give us five words that come to their mind when they think of cities. The responses we got were distinct but connected to ideas of cities as engines of growth, economic development, job opportunities, and infrastructure (schools, hospitals, restaurants, shopping malls, roads). Alongside, an interesting set of responses we received from a quarter of our respondents indicated that they also thought of the city as a temporary place of residence, a place they wished to “escape from” to lead a life. Some defined the city as a “lonely place” and others said it was “sometimes comforting but away from roots”.

Not all perceptions of cities were negative. Some of the people we spoke to said a city was a “safe space”, “a place to find your tribe”, “modern”, “organized and fast paced”. However, most people viewed the city as a place that enabled them to participate in the benefits of economic development, which they felt to be missing in rural regions.

What everyone forgets is that a city is not an isolated space but, an interconnected space, which is dependent on its surrounding areas. This leads to a consideration of the city to be indistinct from the urban, based on the structuralist point of view that the “city” and the “urban” are territorially bound entities.

Continuing with the example of the metropolis of Bengaluru, also considered the IT capital of India the city: it was once known as a city of a thousand lakes. The population has increased from around 5 million in 2000 to over 13 million in 2023. There is no major river located in the region and the city developed along a series of human-made interconnected system of lakes. This system was designed keeping in mind the undulating surface of the city, where overflowing water from one lake flowed into the next, and thus, the region thrived as smaller settlements since the Stone Age. All this changed with urban expansion when many of Bengaluru’s largest lakes were filled in, some converted into a bus station and a sports stadium. The same blindness to the importance of topography and local water resources continues to this day, where lakebeds and the interconnected water channels (as is seen in Figure 3) that feed the lakes are encroached and converted into built spaces such as malls, corporate campuses, and apartments.

Today, urbanisation patterns globally and in India increasingly challenge the seemingly self-evident distinction between city and countryside, urban and rural spaces. Especially in the global South, urban transformation has led to the formation of peri-urban spaces, often viewed as a “place in-between”. They have fluid characteristics of both urban and rural areas and have the highest dynamicity in land cover change and population growth. This is mainly due to the process of urbanisation, where both megacities and their surrounding spaces are linked to each other. Research in peri-urban areas has shown that there is a mutual dependence between the surrounding areas and the urban centres. It is usually the case, where cities import resources, such as water and food, and export their waste and wastewater into these surrounding areas. This is in line with Lefebvre, for whom the urban condition has gone beyond the boundaries of the city and brings together distant spaces, events, and people. Thus, urban can be considered as a set of processes that links places across space and is defined by connectivity. Urbanisation involves the movement of people from rural to urban areas leading to changes in land use influencing the functional capability by impairing the provision of ecosystem services with impacts on the local ecology, biodiversity, hydrologic regime, and other factors. Urban transformation as a process involves a fundamental change in the dominant structures, functions, and identity of urban systems, leading to new cultural, structural, and institutional configurations. This understanding leads to a different framing of urban areas, as complex adaptive “systems-within-systems”.

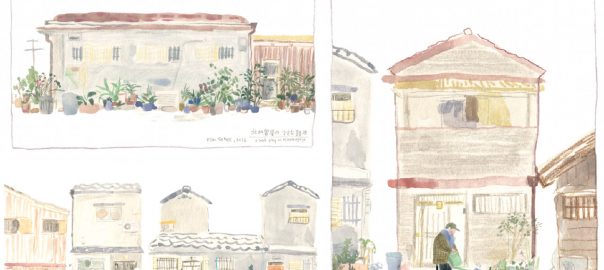

Unplanned urbanisation does not integrate local ecosystems and local needs of communities alienating people and their vital association with ecosystems. This affects people’s access to resources in addition to influencing ecosystem functions both within and outside the jurisdictional boundaries of the city. Policy decisions regarding urban growth are often top-down, devoid of stakeholders’ participation, and lack consideration of ecosystems. This is highlighted by numerous cases across Bangalore, where actions by the state and non-state actors have been undertaken without consideration and discussion with the communities (traditional users) residing along them, raising questions of equity. This is being replicated across areas under urban transformation, an example is the comment by a member of the community in peri-urban Bangalore (shown in Figures 4 & 5), where a lake is being restored “…they [the company who prepared the detailed project report] indicated that they would make space for our cattle to drink water but look they have not made any provision for it. They have built an embankment of stones along the lake, how can our cattle drink water now… once the beautification is completed, the lake will be fenced (Figure 6), and we won’t be allowed to come here”. There are also documented cases where the area surrounding the lakes which were once used as common grazing lands have been converted to urban uses such as playgrounds and parks, thus alienating the traditional users (Figures 7). These approaches have created imbalances within the existing ecosystem and livelihoods of communities, especially the vulnerable. Unprecedented increase in population and the consequent demand for land, and unplanned policy interventions with fragmented governance are threatening the natural ecology of the area.

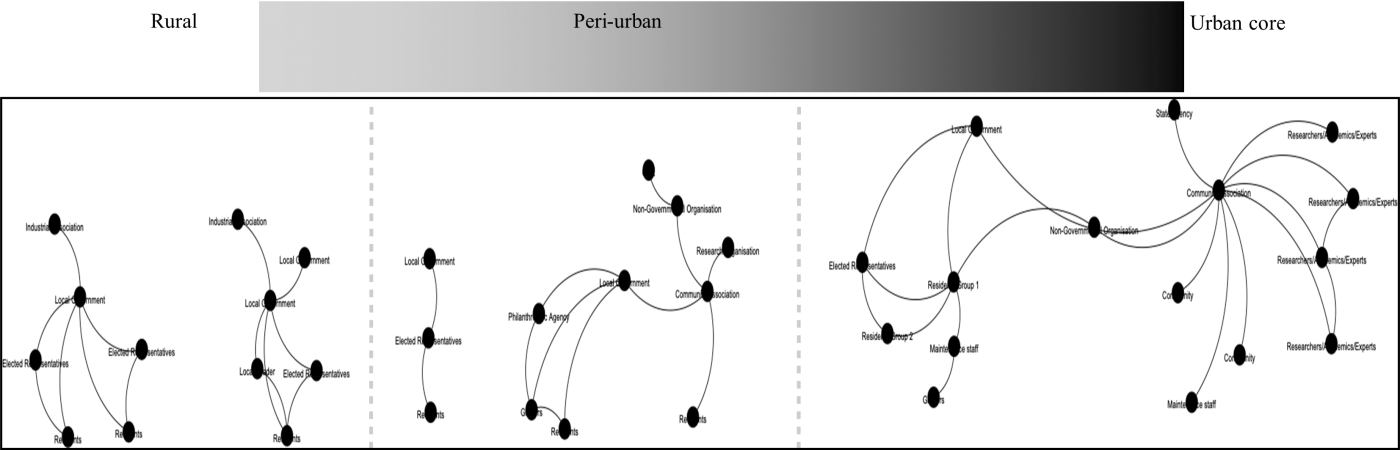

Our recent research along the urban-rural spatial gradient highlights how the actors work within their defined administrative boundaries when working on an interconnected common pool resources such as lakes. Actors typically work on single lakes, creating a disjoint/fragmented effort that does not appreciate the fact that lakes are hydrologically and ecologically connected within watersheds within the region of greater Bangalore. For our research, we selected lakes that fall within a single watershed. Thus, forming an interconnected system where water from upstream urban areas flowed into the downstream peri-urban and rural areas. Further, the selected lakes are located within the administrative boundaries of Bangalore Urban District, but the peri-urban and rural lakes fall outside the limits of Greater Bangalore Municipal Corporation. This provides us with contrasting cases, located within a single watershed but fragmented and bound within administrative boundaries, along an urban-rural gradient with an interconnected lake system. Applying network analysis to capture the role of social actors in governing a connected ecological resource, we see that there is no interaction between actors along the peri-urban gradient – as can be seen from Figure 8, which depicts the number of actors actively involved in the de facto management of eight lakes along the urban-rural gradient As is seen, the actors involved are fragmented within their respective administrative boundaries, indicated in the figure by vertical dotted lines.

There is a clear difference in the number of actors along the urban-rural gradient, with a higher number of actors in the urban core, due to the increased presence of non-state actors (community associations, corporates, researchers, and academics). Non-state actors other than the local community seem missing in contrast in the peri-urban and the rural lakes which are located downstream of the urban core. This increase in the number of non-state actors in the urban core and not in the peri-urban and rural areas indicate that actors involved in lake management bound themselves to work on lakes based on their neighbourhoods and localities with specific administrative boundaries. Non-state actors do not work outside of the administrative boundaries of the city as they “feel that they might not have a say in the issue” as they are not from the vicinity of the lake. The lakes outside of the urban core are managed by the village panchayat or the revenue department and not by the Greater Bangalore Municipal Corporation. As numerous representatives of lake groups have indicated, “the city corporation has been working with citizens since 2010 and we know what to expect and how to work with them”. Thus, the non-state actors choose not to deal with the unknown, unless they find a local leader or representative who will take the lead in dealing with the local administration, which they have no experience working with and have no understanding of the dynamics and power asymmetries among the actors, thus avoiding working in areas beyond their experience and vicinity.

Though we do not capture the presence of direct interactions between actors across the urban-rural gradient, information disseminated on social media seems to play an indirect role in fostering connections. Thus, one community member working on a rural lake said, “…we see how city dwellers are working with the local government and protecting their lakes, we want to do the same.” Information exchange (though unintentional) has helped break certain barriers of the bounded city, by encouraging actors to explore new possibilities to protect their lakes.

In summary, these explorations ― though initial ― show us the importance of expanding our understanding of a city, from a territorially bound and well-defined space based on economic theories of growth, towards incorporation of the city’s ecological and social characteristics, consider a city as a system-in-a-system, interconnected to its peri-urban and rural spaces based on the concept of agglomerations across a landscape. Thus, viewing the city not as a bound entity based on economic definitions, but as a spatially fluid, dynamic distribution of people, processes, and activities connected with ecological systems, which then leads us to consider a city as an interconnected entity. Such an expansive understanding of cities as a connected and complex system will be important if we are to devise strategies to adapt and build resilience in our cities.

about the writer

Harini Nagendra

Harini Nagendra is a Professor of Sustainability at Azim Premji University, Bangalore, India. She uses social and ecological approaches to examine the factors shaping the sustainability of forests and cities in the south Asian context. Her books include “Cities and Canopies: Trees of Indian Cities” and “Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India’s Cities” (Penguin India, 2023) (with Seema Mundoli), and “The Bangalore Detectives Club” historical mystery series set in 1920s colonial India.

Arvind Lakshmisha and Harini Nagendra

Bangalore

Leave a Reply