A view from the joint meeting of the San Juan ULTRA and the NATURA Early Career Network

1. Nature-based Solutions in the Context of San Juan, Puerto Rico

On a sunny day in San Juan, Puerto Rico, life is good. Along the beaches, crabs scuttle in the riprap next to beachgoers posing for selfies on the shore break. Others nap in the shade of fig trees or float in the warm Caribbean waters. Stand-up paddle boarders and kayakers explore the mangroves along the lagoons, where the city’s many small rivers enter the sea. Farther up in the watershed, abuelitas tend to the trees their grandparents planted along the lush riparian “bosques de galería” of the Río Piedras.

Connecting the center of the island to the beaches of San Juan, the Río Piedras watershed embodies both celebration and fear. Heavy rains occasionally transform its calm waters into torrents, inundating the city streets. And when hurricanes hit, the once tranquil sea metamorphoses into a tumultuous and vindictive paramour, unleashing its fury with relentless force.

Connecting the center of the island to the beaches of San Juan, the Río Piedras watershed embodies both celebration and fear. Heavy rains occasionally transform its calm waters into torrents, inundating the city streets. And when hurricanes hit, the once tranquil sea metamorphoses into a tumultuous and vindictive paramour, unleashing its fury with relentless force.

Puerto Rico has a long history of adapting to and recovering from hurricanes. The devastating back-to-back storms of Irma and Maria in 2017 were unprecedented. They shut down the island’s entire energy grid for months, and nearly half the population lost access to water services. Over 60 people lost their lives during the storms, and while contentious, it is estimated that they led to over 4,500 premature deaths.

Not surprisingly, San Juan residents have a high demand for effective flood protection. They are not alone. In many coastal cities worldwide, these challenges are only increasing in magnitude. The effectiveness of coastal cities responding to the challenges of sea-level rise and extreme weather largely depends on their internal capacities and their relationships with larger networks of resources and expertise.

Nature-based Solutions (NbS)―such as restored agro-ecological systems, forests, wetlands, green roofs, and rain gardens―are increasingly considered as means to enhance coastal, urban, and fluvial flood resilience. Yet they must overcome unfamiliarity and an inertial preference for hard-engineered solutions, such as channelized rivers and sea walls, as well as address perceived conflicts over the use of space in dense urban environments.

In June of 2023, our global NATURA Network of early-career researchers and practitioners organized a workshop to examine how these dynamics play out in the context of San Juan, Puerto Rico. With a wide range of expertise ranging from ecology, art, and design to engineering, urban planning, and philosophy, the group has been focused on collaborative methods for NBS planning and design. In San Juan, they learned about and reflected on ongoing initiatives to co-plan and co-design NbS in the city against the backdrop of large-scale flood mitigation projects pursued by the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). One such project centers on the Río Piedras, a biodiverse and socially valued river running through the heart of the city.

2. Río Piedras case study

Following a series of devastating hurricanes in 1978, the Governor of Puerto Rico requested help from the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to design flood control projects across the island. In San Juan, USACE proposed a project to channelize several parts of the city’s main river, the Río Piedras. This “Río Puerto Nuevo Flood Control Project” was approved in 1984 after an Environmental Impact Assessment as required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process. The project was subsequently shelved due to lack of funds.

In 2015, the Municipality of San Juan formed a special commission with interdisciplinary scientists who had conducted research on the social-ecological dynamics of the Río Piedras watershed through the San Juan ULTRA network. Their aim was to explore the utilization of green areas in flood management. This collaboration resulted in a municipal resolution that highlighted the importance of urban green areas for flood management, building upon the city’s 2003 Comprehensive Plan, which recognized the importance of ecological corridors as part of the city’s green infrastructure system.

Another outcome of this collaboration was forming the “Alianza del Proyecto de Canalización del Rio Piedras” (Amigos del Río Piedras) coalition. This alliance of NGOs, state and federal agencies, private practitioners, community-based groups, and residents aims to engage more sectors interested in the sustainable management of the watershed. After Hurricane María, the US Congress approved over $4.5 billion for recovery funds for Puerto Rico. Although the release of these funds has been much slower than in other US jurisdictions, with this funding in sight, the long-dormant USACE revived and reactivated its decades-old river channelization plans.

Many residents had forgotten about these plans, which came as a surprise to community members, many of whom did not even recall the over-30-year-old NEPA process being used for project approval. Thus, they were shocked when contractors began initial site investigations and bulldozers started clearing vegetation along the riverbanks. The USACE plan consists of channeling multiple parts of the Río Piedras, renovating and upgrading existing channels and drainage pipes, and removing the “bosques de galería”, all of which would reduce the ecological value of the Río Piedras, and fundamentally alter the beloved character of the river.

Despite being an urban river, the Rio Piedras has surprisingly high biological diversity; ecological surveys have found over 100 species inhabiting the river ecosystem, including rare endemic species like migratory freshwater shrimp, locally known as the Palaemon, which have endured urbanization but escaped the fate of other Puerto Rican rivers dammed for hydropower development.

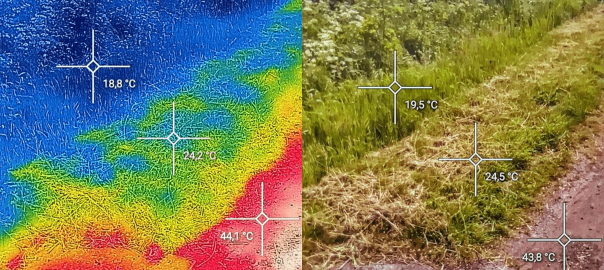

To respond to the proposed alterations of the ecology and function of the Río Piedras, the Alianza advocates for a more equitable process to analyze the causes, impacts, and options for flood mitigation in the watershed. They aim to develop sustainable solutions that enhance overall climate resilience. But also, including the need for community gatherings, recreation spaces, and extreme heat mitigation documented in a series of publications about citizen knowledge systems and a collaborative knowledge-action network. Recognizing the importance of collaboration, they seek to engage with USACE to address the concerns of local communities through a collaborative process.

An ongoing challenge for the Alianza is ensuring the differences in how San Juan communities experience flooding, as well as their varying access to resources and ability to adapt, are heard and adequately addressed by the USACE and local government. Addressing these internal differences requires sensitivity to those needing immediate flood protection while balancing demands for alternative and greener solutions. Another challenge is the risk that opposing the USACE plan could forfeit funds to address current flooding issues. The Alianza navigates this delicate situation by challenging the project’s assumptions, seeking genuine participation, and ensuring that affected voices are heard.

The top sign warns of a fine for garbage dumping, the bottom sign mentions “The Ecological Corridor of Río Piedras” community project

The Alianza contests several assumptions underlying the USACE plan. Outdated projections for population growth, urban development, low-resolution characterization of land cover, and associated peak flood estimates all mean that the proposed concrete channel is oversized. The Alianza also contends that extensive concrete dikes will lower water levels within the river during dry spells, leaving much of the remaining flow to come from sewer systems that need their own upgrades.

Given USACE’s extensive technical expertise, the Alianza urges them to address these concerns within their modeling and design processes. They want the agency’s unit of “Engineering With Nature” (EWN) to review the project to determine if there are design alternatives to manage flooding in the Río Piedras that incorporate ecological components like green infrastructure. The EWN is becoming a global source of expertise actively seeking to incorporate Natural and Nature-Based Features into flood resilience projects (NNBF), even hosting a symposium in May of 2022. While initially resistant, USACE appears to be increasingly open to collaboration due to sustained pressure from community members, members of Congress, and federal agency representatives.

Broader changes are also at work as USACE’s approach towards flood mitigation evolves, they must also overcome perceived and very real barriers to building rapport and trust with communities that have been colonized over centuries and are skeptical of plans and projects imposed on them.

Overall, the Alianza and the local community are demanding fair and transparent processes for understanding the causes and impacts of flooding, including the relationship between flood mitigation options and the values, fears, and concerns of San Juan residents. These can be addressed by collaboratively building representations of the urban system, more broadly considering social-ecological relationships, and explicitly evaluating how citywide NbS fit within a more comprehensive climate resilience strategy.

Overall, the Alianza and the local community are demanding fair and transparent processes for understanding the causes and impacts of flooding, including the relationship between flood mitigation options and the values, fears, and concerns of San Juan residents. These can be addressed by collaboratively building representations of the urban system, more broadly considering social-ecological relationships, and explicitly evaluating how citywide NbS fit within a more comprehensive climate resilience strategy.

This alternative approach contends that flooding of the river is not the main problem, but rather a more complex situation that cannot be resolved with single technological solutions like channelization. Turning the Río Piedras into a channel does not address the causes of flooding nor does it account for climate uncertainty. What’s more, while the Río Piedras channelization was conceived and proposed in isolation, it intersects with numerous other USACE projects for dredging in the San Juan Bay and restoring urban waterways. Nevertheless, the cumulative impacts of these projects on ecosystems or society have not been evaluated.

3. The NATURA Workshop

During the first day of the three-day workshop in San Juan, members of the ECN learned about various proposals for more integrated blue and green infrastructure solutions for flooding in other sections of the city. Several thorny wicked issues were exposed, namely that in very low-lying areas, green infrastructure will not be able to absorb projected flood waters without removing upwards of 30% of buildings within the district. Such wicked trade-offs will likely arise in other low-lying coastal areas, prompting tough conversations around planned retreat and large-scale urban reconfigurations. Cities that can engage in such projects proactively will have a much better chance of weathering accelerating rates of sea level rise and extreme weather than those that are forced to react.

Members of the ECN also explored strategies for collaborative framings of urban flooding challenges and collective envisioning of desired urban and island future scenarios. While the full report from the workshop is forthcoming, initial insights were that often the causes of urban flooding are not due to simple land use changes and hydrology, but rather the political processes that govern land use and flood management. In this view, human decisions around infrastructure and land used create uneven vulnerability and path dependency in how we respond to flood challenges. Similarly, explorations of future scenarios explored the connections between diverse economic sectors like agriculture, materials handling and recycling, manufacturing, and urban planning, and economic and political self-determination. One group even envisioned a resurgence of the Antillean Confederation, or a political organization of small island states in the Caribbean, which would organize for collective well-being through interdependent economic and political development.

Other elements of these futures included complete circular economic development, restoring fisheries by converting submerged buildings into reef habitats, building closed waste-to-energy systems, elevated cable cars and other mass transit options, and even an endemic freshwater shrimp (Palaemon) smart city disco. Such radical departures from the status quo may seem improbable to some, but if we learned anything in our time in San Juan, it is that those without dreams often have their lives dreamt for them. If cities around the world are to transform in advance of climate change, it will be through bold and visionary means that throw off the status quo of complacency in the face of bureaucratic and infrastructural inertia.

Preemptive adaptation in coastal cities requires a transformative approach, embracing the value of local community knowledge and legacies of uneven infrastructure. The power imbalances that skew decision-making processes need to be recognized and confronted. By acknowledging these imbalances, we can work toward developing alternative ways of managing urban watersheds that are more inclusive and equitable. Community members are local experts with memories and lived experiences that must be acknowledged within the development of NbS. Their insights can provide valuable guidance and ensure that solutions are tailored to local needs. Participatory design and planning methods, premised on the notion that local values, experiences, and priorities are legitimate and credible, can effectively help bridge the gap between local preferences and technical planning and design.

4. The Future of NbS in San Juan and Beyond

Against monumental challenges, Puerto Ricans find strength in unity. When the rains pour down and the streets become rivers, neighbors come together to help each other, forming human chains to pass sandbags and protect their homes from the rising water. They open their doors, offering shelter to those displaced by the storm, and share their food and water reserves. Volunteers from all walks of life, armed with shovels and tools, join forces to rebuild what was lost. When the rain ends, the city resonates with the sounds of hammers, saws, and laughter. Working together, communities construct sturdier homes and stronger foundations under the scorching sun and vibrant music, matching the loud colors of murals on buildings and overpasses. Boricuas are creative and resilient people; all they ask is to work together with federal agencies to collaboratively address their concerns while achieving USACE’s mission to protect their lives and property.

The flooding issues of the Rio Piedras are exacerbated greatly in the coastal zone. Like many coastal cities, it inhabits the junction between freshwater rivers, the built environment, and the ceaseless dynamism of the sea. Salt spray and pounding waves leave their marks on buildings and coastal infrastructure, rapidly aging new structures. Freshwater rivers provide a vital lifeline for humans and ecosystems alike can also be overwhelmed by heavy rains. Mangroves and salt marshes are in constant motion. Wave action relentlessly exposes the local bedrock until its erosive force is balanced by sediment delivery from streams and rivers. Coastal cities require continuous human interventions to maintain their form and character: washing the salt spray off the windows, filling the cracks in the sea walls, unclogging the sand from the stormwater system, and dredging harbor channels. Long-term solutions to coastal sea level rise must consider the balances of these titanic and microscopic forces and their relationships to the ecological and built solutions proposed for extreme weather and flood mitigation.

The residents of San Juan are not alone in their struggles. Coastal communities worldwide are grappling with interdependent challenges of rising sea levels, extreme weather, and constraints on resources and imagination available to respond to disastrous events. These factors combine to escalate the frequency and severity of coastal, pluvial, and riverine flooding, endangering lives, and the very fabric of cities, with varying impacts on humans, ecosystems, and the built environment. The coast has always been a dynamic environment; sea level rise exposes the weakness of existing infrastructures and the paradigms that design and maintain them.

Living in an era of unprecedented social inequality and environmental change likewise exposes inequalities in technical capacities and social power required to address climate justice. Embracing NbS as part of the adaptation toolkit does not offer a panacea. Rather, it offers a way of thinking that seeks to work with nature rather than against it. Our commitment to transformative NbS likewise does not seek to resolve social differences but to embrace processes through which diverse perspectives and approaches lead to more robust problem formulations and potential solutions. For better or for worse, coastal communities have always navigated these challenges; their prosperity is drawn from the sea even as they live in the shadow of its storms.

By continuing to build connections across countries, cities, and communities, we in the NATURA ECN hope to bridge dialogue from the global to the local. Our work, including the forthcoming Compendium of Participatory Methods for NbS, will continue to develop tools and approaches to improve human and ecological relationships in an era of unprecedented and rapid transformation.

Zbigniew Grabowski, Laura Costadone, Erich Wolff, Mariana Hernández, Yuliya Dzyuban, Marthe Derkzen, and Loan Diep

Hartford, Norfolk, Singapore, Sacramento, Singapore, Arnhem/Nijmegen, New York City

about the writer

Laura Costadone

Dr. Laura Costadone is an Assist. Research Professor at Old Dominion University for the Institute for Coastal Adaptation and Resilience. Laura brings her expertise in co-design and co-create pathways to uptake and implement urban sustainable development goals by engaging directly with municipalities, practitioners, decision-makers, and citizens.

about the writer

Erich Wolff

Erich Wolff is a Research Fellow at the Earth Observatory of Singapore and the Asian School of the Environment at Nanyang Technological University (NTU) Singapore. His research delves into the challenges of implementing nature-based solutions in the Asia Pacific region and explores the role of communities in the development of green infrastructure.

about the writer

Mariana Hernández

Mariana Hernández is a PhD student at the University of Manchester. Her areas of expertise include biodiversity conservation, multi-criteria analysis, vulnerability and resilience of complex systems, socio-environmental studies in global south cities, and scientific communication to inform decision-making processes and foster positive environmental outcomes.

about the writer

Yuliya Dzyuban

Dr. Yuliya Dzyuban is a Research Fellow at Singapore Management University for the Cooling Singapore 2.0 project exploring the impact of vegetation on urban climate and perception of heat. Her area of expertise lies in using mixed-methods approaches to uncover relationships between urban morphology, microclimate, and human wellbeing.

about the writer

Marthe Derkzen

Dr. Marthe Derkzen is a researcher and lecturer with the Health and Society chair group. She studies urban nature from a social justice perspective with an interest in climate adaptation, local food, healthy neighborhoods and stewardship of the commons.

about the writer

Loan Diep

Loan is a researcher in environmental studies. Her work is centered on the development of cities that are green and inclusive of communities, most particularly those trapped in marginalizing systems. Her PhD focused on green infrastructure for rivers in informal settlements of São Paulo.

Acknowledgements:

The NATURA ECN would like to thank Tischa Munoz-Erickson, Elvia Melendez, Miriam Toro Rosario, Cynthia Manfred (Guarda Río), and others in San Juan ULTRA and the Alianza for the opportunity to learn about flooding and NbS issues in San Juan.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation