Mainstreaming mutual aid as a result of the pandemic and compounding crises broadens how we understand the limitations of social infrastructure; these sites are crucial, and they deserve increased investment in the near term as we continue to organize for better options.

Social infrastructure and so-called “third spaces” (the non-work, non-home gathering spaces ― either public or private ― like parks, libraries, houses of worship, and coffee shops where people spend time) are a crucial part of the lifeblood of civic life, particularly in cities. These are spaces where people come together, form relationships, and are in forced proximity with others, regardless of whether or not they come from the same geographic and demographic communities. Much has been written about the importance of these spaces and their unique role in building social resilience and supporting community organizing, particularly after a disaster or disturbance. Examples from past crises, such as Superstorm Sandy in New York City, illustrate how public parks, houses of worship, and community centers can become hubs for donations and distributions of essential supplies. In the quieter times between extreme events, these spaces are activated by civic groups that encourage civic engagement and build greater trust and community cohesion. The unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and the need for social distancing shifted the role of social infrastructure in disaster response organizing in multiple ways ― both in how it was activated and how it was framed ideologically. Understanding the benefits and challenges of social infrastructure in 2024 requires looking at its uses and conceptualizations in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the civic organizing that emerged.

In March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic spread around the world, government-enforced lockdowns and pleas for social distancing altered our relationships to space and place. Office workers shifted to remote work options and spent more time than ever in their private homes. In large cities where space was limited, many people with financial means bought houses in suburban and rural areas in order to get access to more space. Public parks were initially left empty and then later overwhelmed with visitors as public knowledge about virus transmission trickled out, and many added creative social distance indicators to try to keep people safe.

Photo: Noam Galai/Getty Images

As city dwellers grappled with their new, often smaller, geographies of home, many were also waking up to the extreme disparities in how the pandemic was impacting people based on racial identity, age, and disability status. The “twinned crises” of COVID-19 and ongoing racialized police brutality came to a head in the summer of 2020, and emergent civic groups were a driving force in the response.

Early in the pandemic when many civic groups were pivoting to COVID response and emergent mutual aid groups were forming in droves, online organizing was the only option to keep everyone safe. This offered flexibility for people to participate on their own time, but many organizers and volunteers soon felt the limitations of online spaces acutely. Organizers who had previously relied on physical spaces to gather in person and collect tangible donations adapted quickly to shift to online networks, but missed the home-base of a physical space (Landau et al., 2021). Online organizing events in the early days of the pandemic were primarily held on Zoom. While this allowed people to participate from the safety of their homes, internet access and comfort with technology blocked participation for many, particularly older community members. In-person connections, especially those happening in outdoor settings, allowed members of new civic groups to meet and form connections in person but were still primarily advertised in online spaces and social media. In interviews with mutual aid groups, organizers and participants shared that it could be harder to create deep relationships without in-person, face-to-face interactions. Terra Incognita, a research project from NYU and New_ Public, mapped the “digital spaces” created during the pandemic in New York City and explored the creation and curation of online public spaces including educational programming through public libraries, virtual synagogue services, online exercise classes, and mutual aid organizing. In the organizing example, they found the online space was not sufficient for community building. “For the Brooklyn mutual aid groups, although they formed online, it was difficult to gain access to them without making direct in-person connections, such as volunteering at a neighborhood food pantry. Publicness was in this sense mediated by access online and offline” (p. 41).

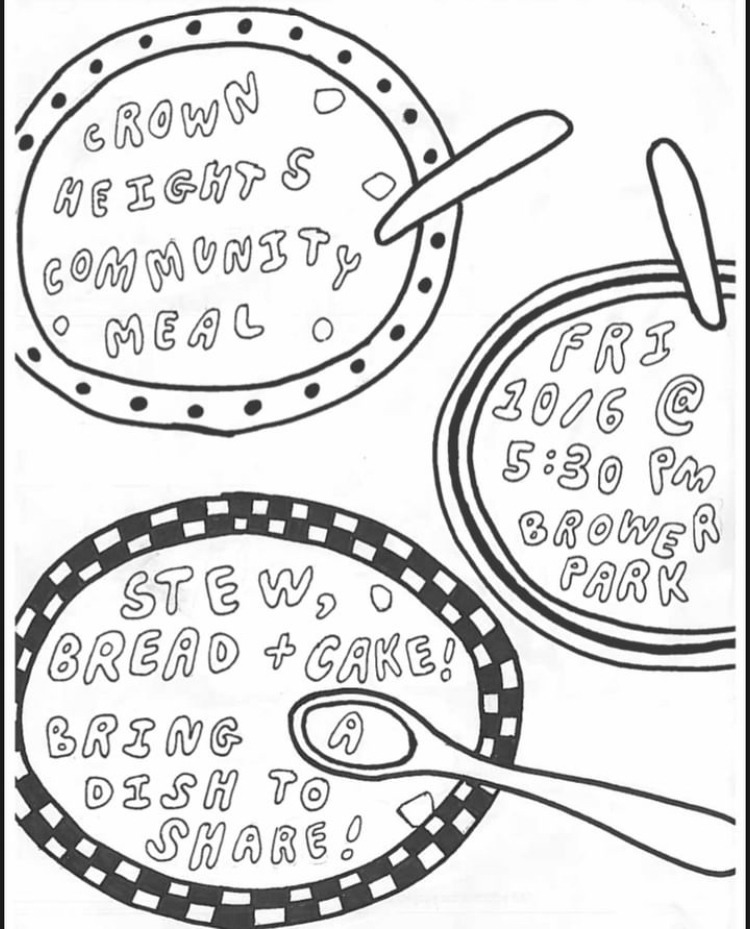

As time went on and the COVID-19 vaccine rolled out, gathering in person, including the option to meet indoors during colder months, brought a new layer of community building. Pre-existing civic groups and post-COVID mutual aid groups utilized local churches, community centers, parks, local bars, and community gardens, as meeting and event locations. My own mutual aid group, Crown Heights Mutual Aid (CHMA), formed an essential relationship with a local pastor and his wife, who offered their space for meetings and community parties that included grocery giveaways, a free store, a hot meal, and music to keep the mood lively and social. These events built bridges between long-term residents of Crown Heights, many of them older people of color, and the younger, whiter, group of new residents who started CHMA.

While many civic groups use spaces like churches, parks, and libraries in a similar way, the framing and language around social infrastructure and public space matters. The surge of local mutual aid groups that formed following the pandemic brought anarchist political thinking closer into the mainstream with their critique of the state and emphasis on abolition and networks of solidarity over traditional state and market solutions such as incarceration and charity. Anarchist mutual aid responses offer an alternative conceptualization of social infrastructure and public space, one that views public spaces as having the potential to be emancipatory when they are sites of deliberative democracy ― spaces where various publics of different classes and backgrounds can interact and create governing structures outside of traditional hierarchies. Using this framework, though, sites of social infrastructure run the risk of being reduced to a source of social capital, which can be co-opted by the state to encourage community participation in their own agendas as they defund care for public spaces (Firth, 2022). Thus, these spaces are constantly in a battle between those who want to expand the autonomy of public space through actions like protests and parties, and those who want to restrict it with increased surveillance and hostile design interventions that prevent people from comfortably gathering or sleeping (Springer, 2016). Public spaces are often privatized by neoliberal policies that restrict access and use, and the anarchist response of “creating or seizing them from below” (Firth, 2022, p.140) understands the exercise of reclaiming the commons as its own form of mutual aid. In practice, this can look like anything from organizing mass occupations of privatized public spaces (as in the Occupy Wall Street movement), to setting up neighborhood food services in the local park, which CHMA has recently started doing on a regular basis.

Mutual aid is often framed as existing outside of traditional aid structures, both state and private. The use of publicly funded spaces by mutual aid groups illustrates the blurriness of the line between state and non-state, but as Dean Spade says, “Being an anarchist does not mean avoiding engaging with the governments we live under” (Spade, 2023). Social infrastructure is not only a tool for current mutual aid organizing, it is a springboard for imagining a more equitable world. Mutual aid infrastructures include public spaces where people can meet to organize or negotiate conflict with some anonymity. But they need to go beyond that as well, as Dean Spade points out:

We need new skills to depart from a system for solving conflict based on a centralized authority that determines who is good and bad. We want to build a decentralized approach to solving conflicts focused on recognizing that everyone is worthy of care and that no one is disposable. What if we all had more skills to solve problems in our communities? Endemic problems like child sexual abuse or sexual assault, gender-based violence—those harms are not going to be solved by a central authority, particularly since the authorities are primary sources of that violence… And so I do think it is infrastructure. It is particularly about building complex, flexible, responsive, decentralized infrastructure. (Spade, 2023)

Thinking broadly about social infrastructure can make room for the skills that community members rely on when they support one another or intervene in a conflict. Community-based interventions that rely on relationships of mutual trust are more effective than carceral systems of punishment, and these relationships, as well as opportunities for new people to gain skills and grow trust, are social infrastructure as well.

The mainstreaming of mutual aid as a result of the pandemic and compounding crises broadens how we understand the limitations of social infrastructure; these sites are crucial, and they deserve increased investment in the near term as we continue to organize for better options. But they are limited without a growing investment in social safety and a loosening of the restrictions that keep them from being free spaces. As Ruth Wilson Gilmore teaches us, abolition is not about absence but about presence ― presence of mutual support, shared resources, and communities of care. Taking these lessons, and the framework of an “infrastructure of mutual aid” (McKane et al., 2023), can offer us a way forward to thinking about social infrastructure as transformative infrastructure in the post-pandemic age of compounding crises.

Laura Landau

New York City

References:

Ansfield, B. (2023, October 30). New Interview about Abolition and Infrastructure in Radical History Review – Dean Spade. https://www.deanspade.net/2023/10/30/new-interview-about-abolition-and-infrastructure-in-radical-history-review/

Campbell, L. K., Svendsen, E., Johnson, M., & Landau, L. (2021). Activating urban environments as social infrastructure through civic stewardship. Urban Geography, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1920129

Firth, R. (2022). Disaster Anarchy: Mutual Aid and Radical Action. (1st ed.). Pluto Press.

Landau, L. F., Campbell, L. K., Svendsen, E. S., & Johnson, M. L. (2021). Building Adaptive Capacity Through Civic Environmental Stewardship: Responding to COVID-19 Alongside Compounding and Concurrent Crises. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 3, 705178. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2021.705178

McKane, R. G., Greiner, P. T., & Pellow, D. (2023) Mutual Aid as a Praxis for Critical Environmental Justice: Lessons from W.E.B. Du Bois, Critical Theoretical Perspectives, and Mobilising Collective Care in Disasters. Antipode, n/a(n/a). https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12986

Leave a Reply