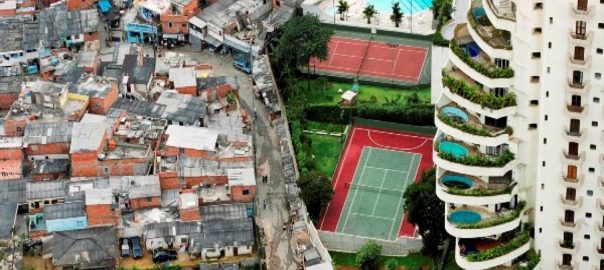

What is particularly of concern is the lack of action in many disadvantaged communities where historic and current inequities in funding, decision-making, siting of industrial and transportation facilities, and access to nature make residents especially vulnerable to climate impacts.

Looking out from my office in lower Manhattan, preparations for rising seas and coastal storms are becoming real. As I type these words, construction crews are cutting scores of mature trees that once graced the local parks to make room for a system of about five-meter-high berms, flood walls, and deployable barriers. Together with dry- and wet-proofed buildings and infrastructure, these measures are intended to prevent damage from coastal flooding for five kilometers of the City’s shoreline.

Losing precious greenery in our city is never easy. The initial plan put forward by the city government and a state-run development authority sparked community concern and opposition. It’s a fair argument to say that renaturing and retreating from one of the most densely developed business districts on the planet was not really an option (at least for now). And, ultimately, given local memory of flooding from Hurricane Sandy in 2012 and the resources available for this neighborhood, a modified plan is going forward. It provides for the replanting of trees and shrubs as well as new landscaping that will help integrate the new coastal infrastructure into the neighborhood and people’s lives. It’s a sad day for the trees and the wildlife and people (like me) who enjoyed their benefits, but it’s also true that these changes are relatively minor notes in the long story of our ever-changing urban waterfront.

Our seas are expected to rise by at least two meters by 2100 and the probability and reach of coastal storms are increasing as well. But not all the people and neighborhoods that line the Hudson River estuary in New York and New Jersey are currently considering safeguards like the ones I see being erected in Manhattan’s financial district. What is particularly of concern is the lack of action in many disadvantaged communities where historic and current inequities in funding, decision-making, siting of industrial and transportation facilities, and access to nature make residents especially vulnerable to climate impacts. These communities are some of the places most in need of shoreline enhancement.

But our experience is that, if offered support, these communities are eager to engage and take part in developing a response to climate change. A recent targeted grant program instituted by the Hudson River Foundation offers some insight into how community-led efforts can be supported.

Brooklyn’s Coney Island, a neighborhood that also experienced devasting floods in 2012, is a case in point. Despite a number of City and State-led initiatives to address long-term resiliency in the area, the plans for shoreline berms and possible tidal barriers on Coney Island Creek have not advanced. To be sure, protecting the people, homes, and businesses on this former barrier Island is a complex technical challenge that has been the focus of government-led planning efforts. But in the eyes of community leaders like Pamela Petty-John of Coney Island Beautification, the cause for inaction is also a disconnect between community needs and desires and the will and ways of government.

Indeed a key objection of a coalition of community organizations and environmental groups to the concepts being discussed in the United States Army Corps of Engineers Harbor and Tributaries Focus Area Feasibility Study (HATS) is that the Corps’ existing cost-benefit calculations reinforce existing inequities by “undervaluing” waterfronts features in poorer neighborhoods and not addressing community-expressed needs. Specifically, the Corp’s process relies on calculations of existing property values and public parks, an impediment for neighborhoods suffering from a legacy of institutional disinvestment. As a result, the study, which is key to unlocking billions of federal, state, and local capital dollars, is missing an opportunity to address flooding issues of concern to community members as well as other potential co-benefits ― remediation of water quality issues and providing waterfront access.

Bridging this gap requires making community knowledge and values an integral part of data gathering, project formulation, design, implementation, and on-going monitoring and management. Such understanding reflects the observations and lived experiences of people living or working in the project location. This is especially important for initiatives located in or otherwise intending to serve disadvantaged communities. Too often a lack of access to planning processes, political power, and cultural differences has disconnected residents and businesses in these areas from these decisions. The result can be poorly conceived projects, or decision-making paralysis resulting from disagreements between the responsible government agencies and local stakeholders. Our changing climate makes getting things right ― and quickly ― an urgent need.

To help meet this moment, the New York – New Harbor & Estuary Program (HEP) has sought to advance climate resiliency planning and education through a series of grants that prioritized disadvantaged communities. A collaboration of government, civic organizations, and university scientists established by the federal Environmental Protection Agency and the states of New York and New Jersey, HEP and our hosts at the Hudson River Foundation, have a long history of supporting partnerships in estuary management.

The creation of this program, which resulted in more than one hundred proposals from local stewardship organizations or their partners, are small snapshots into the expressed needs of frontline communities for assistance and provide a framework for how funders can advance community-led resiliency initiatives.

Our effort is the result of recent federal initiatives in the United States to accelerate the pace of coastal investment and adaptation, funded by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs (IIJA) and Inflation Reduction Acts. Importantly, this includes significant funding for advancing projects outside of the strict context of disaster recovery/rebuilding or even hazard mitigation. This presents opportunities to advance proposals featuring natural and nature-based resiliency features, or otherwise delivering important water quality, habitat, public access, and other benefits for the local community. Specifically, Executive Order 14052, the Justice40 Initiative, mandates that at least 40% of this funding reach disadvantaged communities.

Thanks to the federal funds provided by the IIJA, HEP recently released its RFPs to underwrite community-led resiliency efforts aligned with our collaboration’s water quality, habitat enhancement, and public access goals. To ensure that the terms of the RFPs would be responsive to the needs of communities, HEP engaged in a series of conversations with local and national environmental justice leaders. Based on that input, we relied on multiple definitions of “disadvantaged communities” to identify qualified communities, incorporating federal guidance, state definitions (that incorporated race as a criterion), and HEP’s own definition (that reflected inequities in access to water). The RFP process itself was structured to provide low barriers to entry (with an initial letter of inquiry, standard forms, and transparent criteria). Expenses for organizational capacity building and administrative expenses, especially hard to fund for groups in poorer communities, were allowed.

Our goals were explicit as well:

- Enable disadvantaged communities in the Hudson―Raritan Estuary to fully participate in planning and decisions about coastal adaptation, habitat enhancement, and other infrastructure projects being advanced by federal, state, and local agencies. Proposals that can describe how community input could be incorporated into the federal, state, or local decisions or otherwise demonstrate coordination with the lead project agency were particularly encouraged.

- Advance community-initiated projects that will enhance climate resiliency, including shoreline improvements, stormwater management measures, and natural and nature-based resiliency features. We were especially interested in projects that will help communities gain access to future federal and state infrastructure funding opportunities and demonstrate how to incorporate social vulnerability of communities to make better-informed decisions.

- Address gaps in data and knowledge that will improve community and agency understanding of baseline conditions, the current and future impacts of climate change, community values, and/or the effectiveness of alternative adaptation measures and management strategies. This could include efforts to assess the state of existing knowledge as well as the development, implementation, and evaluation of educational programs. Projects that engage community members to participate in the co-production of required data and knowledge are especially encouraged.

- Demonstrate the power of collaboration between community, government, independent scientists, and/or utilities. Addressing climate change and enhancing habitat in our urban estuary requires a team effort. Proposals that engage multiple stakeholders or seek to establish successful community involvement in such partnerships are highly desired. Using the arts, recreational programs, and experiential learning to bring messages about climate change and resiliency to local waterfront parks and public spaces is appreciated.

The response was great, reflecting the appetite of community-based organizations. Altogether, we received 107 requests for assistance totaling $ 4.1 million. To date, and based on currently available funds, we are able to support about a third of those organizations with 35 grants totaling $ 612,000 for projects ranging from support for co-producing data on flood risk to community-managed engineering consultants to community-led tree planting and habitat restoration efforts to arts-forward community engagement programs. Additional funding anticipated from the IIJA over the next three years will enable us to meet more of this documented need from current and new partners.

While our programs are certainly not the biggest source of assistance available, what we gleaned from the process points to needs, challenges, and opportunities that are also confronting much larger public and private sources of philanthropy for community-led efforts.

For most community organizations, the focus is on authentically and accurately articulating their problems and needs to community stakeholders and the relevant authorities: What are the climate-driven risks? Who will be impacted? What are acceptable solutions/what is the desire for other improvements? How can we effectively organize to ensure these needs are met? These organizations help co-produce needed knowledge, bringing community understanding to the problems confronting the waterfront while at the same time building community support for the proposed solutions.

Another key challenge is about process. Many community members are wary (and weary) of the usual workshops and engagement tactics. Just too many past experiences of public planning efforts going nowhere. Right-sizing engagement efforts and making it easy and even fun to be part of the conversation is key. The familiar community organizing maxim of engaging local residents and businesses where they live is critical, including leveraging existing forums and community festivals. Using cell phones and social media to document the issues and bringing discussion of the issues to existing community institutions and events can help keep the usual suspects engaged and bring new voices to the discussion.

Of course, enabling the community to move from conversations to seeing positive changes on the ground is the best way to avoid the risk of planning fatigue. Ensuring that expressed needs are incorporated in the design, and the final engineered and permitted project requires honesty and transparency in the process. Enabling community organizations to have the means and, importantly, the internal capacity to hire and manage their own trusted technical consultants can help ensure that viable solutions are fairly considered. Just as important, it can allow for unrealistic expectations to be forthrightly addressed early in the process. Every construction project ever conceived requires on-going compromise in terms of design, budget, and delivery. However, bringing and keeping the community and agencies together can help ensure that those changes do not derail the effort or the people who have to live with the results.

We are proud to say that HEP is now supporting the important work of groups like Coney Island Beautification. Building on their history of effective organizing around the development of public parks, water quality improvements, and community greening, the community-based Coney Island Beautification has established an effective partnership with the New York Aquarium/Wildlife Conservation Society and engineering consultants which are lending technical support and additional capacity for this work. They have started hosting community meetings intended to establish a resiliency vision from the ground up, incorporating multiple means of resiliency and potential co-benefits of public access and water quality from the start. The intent is for this conceptual plan to provide a framework for recasting (and hopefully advancing) the many prior government plans in the area.

Of course, these conversations are just starting, and Coney Island is still years away from implementing specific measures. But taking the first steps with the community (as opposed to in or even for the community) is offering some promise for our precarious future.

Rob Pirani

New York City

Leave a Reply