A biking lane should measure 4.20 meters at minimum in the city of Utrecht. Sidewalks need to be 1.20 meters wide to make sure pedestrians and a person in a wheelchair can pass each other. For each house we build we add 0.78 parking spaces in the public domain. In the Netherlands, we have a lot of standards and guidelines for our public space. In a project, this usually means that the ‘left-over project area’ is used for green. And in a densifying city, this often amounts to little substantial green. With even less room for elements that add to the nature-quality of the space.

So, in Utrecht, we challenge the standards with norms for nature.

Setting a standard for nature

Of course, every project wants to add nature to their development. But once all Dutch standards and guidelines used in projects are added up, not much room is left for green. So, at the end of a project, adding effective green or nature adds up to more costs than anticipated in the beginning. And the high ambitions, which were formulated at the beginning of the project, are reduced to low-quality green of marginalized nature. By making it metric by listing a specific standard, we raise the bar on nature ambitions in projects and we measure the impact the project has on a certain species. Real impact. Not ‘nature-washing’ but a quantifiable nature-positive impact.

Building blocks for nature

In Utrecht, we developed “building blocks for nature” for five species. We made the habitat required in development plans conform to a quantitative minimum, or a metric. The easiest of the five was a wild bee species (Chelostoma rapunculi), which depends on bellflowers for its pollen. The most challenging target the Smooth Newt (Lissotriton vulgaris), which needs ponds with aquatic plants for breeding and bushes or rocks for hibernation. By defining the metrics of required habitat, we give landscape architects more specific guidelines which they need to incorporate in their design. It also helps in the evaluation of a project design. For example, does the plan meet the required targets set for one or more of the five species?

Nature made easy

To build a well-functioning habitat for the bellflower wild bee the project needs to include 50m2 of nesting grounds (per hectare) with dead wood and brambles; 100m2 of feeding area (per hectare) with a minimum of 2125 bellflowers and four other flowering species such as Common Mallow and Purple Loosestrife. Another requirement is the distance between the nesting area and the flower area; these should be within 100 meters of each other. This habitat should be easily feasible within every project and reflects the minimum of our standard. By making it metric you do not need to be an ecologist to incorporate this wild bee species in your plan. An ecologist is just needed to check the design of the required areas and if all the habitats are incorporated.

No “nature-washing”

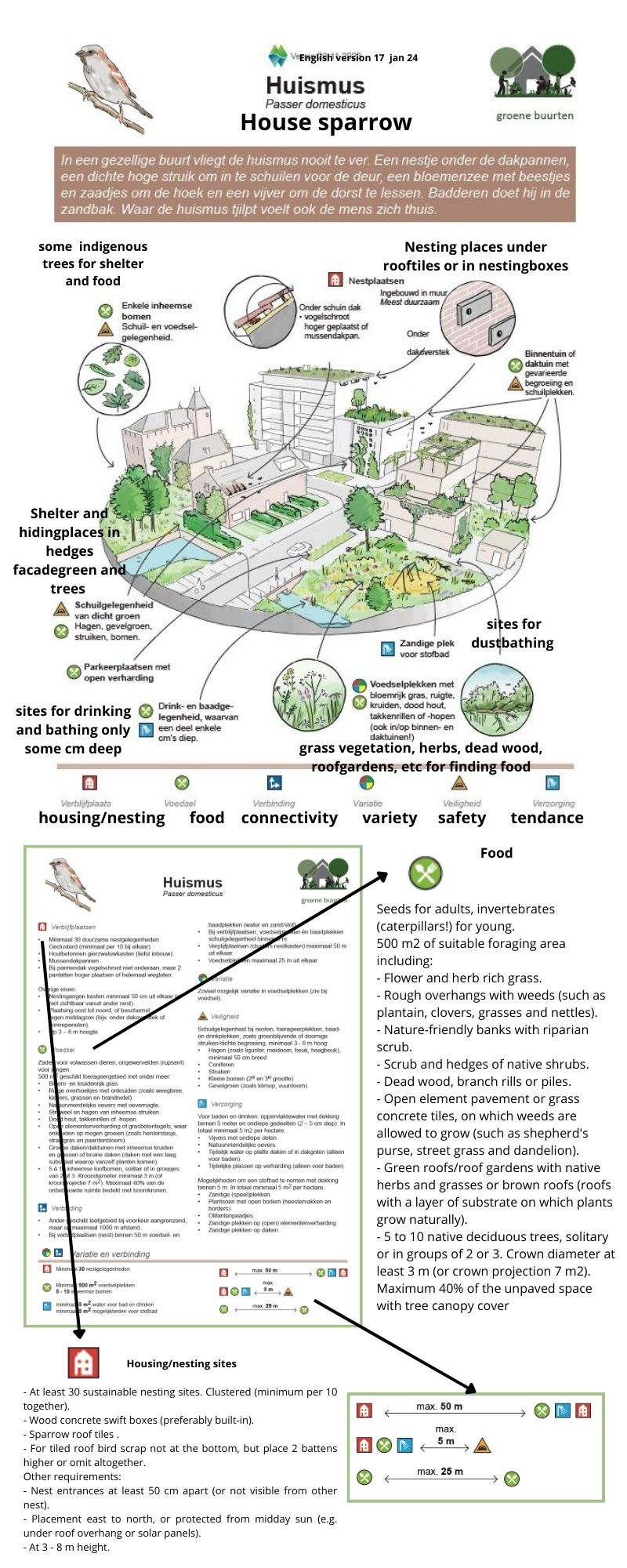

The house sparrow (Passer domesticus) is a more difficult-to-reach target. Especially when we make this a target species for urban development with a high building density: the Merwede Kanaalzone (https://merwede.nl). In this project development, the aim is to build 250 houses per hectare. According to our nature-standard, the house sparrow requires at least 30 nesting boxes (per ha) 100 m2 (per hectare) of vertical green (shrubs or green wall vegetation) for shelter; 500 m2 (per ha) of feeding grounds such as (rooftop) gardens or parks and at least 10 solitary trees. Shelter should be available at 5 meters distance of the nesting boxes, the feeding areas should be found within 100 meters of the nesting boxes and planted with indigenous species. With these standards, we make nature targets quantifiable. Ecologists, landscape architects, and the project developer all know what is needed at the beginning of the project to achieve a nature-positive development. At the end of the project, it is possible to make the targets reached quantifiable. Whether nature (or the targeted species) agrees is a question of time. And a nice incentive for monitoring the project with future residents.

A nature-positive development

Of course, nature is more than a checklist. An ecologist is still needed in the project to collect information on patches of green and blue that need to be spared so species can colonize the new area from these “safe spots”. The ecologist also needs to make sure connections to surrounding green are made and identify other chances for adding nature to the project. On top of making sure the above-mentioned requirements are met and executed in the ecologically right way. Making nature metric helps to test all the other standards we put into a project and question them on necessity next to one another.

I look forward to hearing from other cities how they claim room for nature in high-density urban developments.

Gitty Korsuize

Utrecht

Further reading:

https://waarneming.nl/species/24463/

https://waarneming.nl/species/448/

About the Writer:

Gitty Korsuize

Gitty Korsuize works as an independent urban ecologist. She lives in the city of Utrecht. Gitty connects people with nature, nature with people and people with an interest in nature with each other.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation