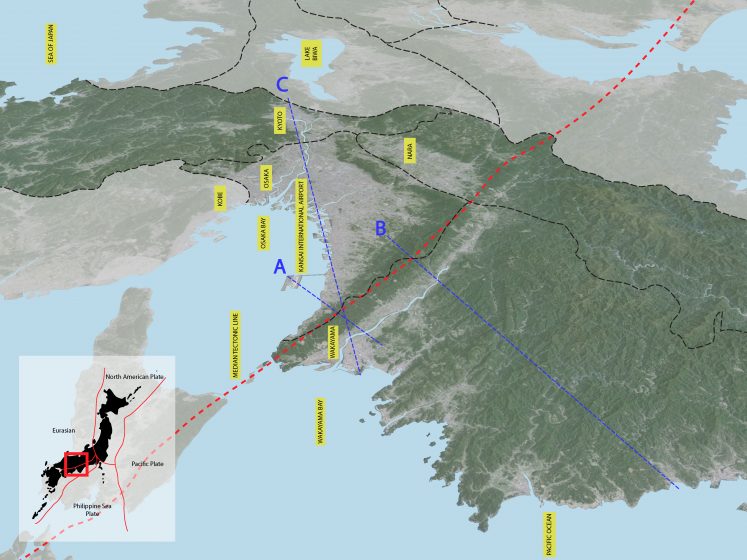

Kansai is both an international airport built on an artificial island in Osaka Bay and an urban megaregion sprawling across Japan’s largest and most populous Honshu Island. But Kansai also affords countless walks in which to understand landform heritage and ecology. The Osaka Sea is embraced by two mountainous areas, one facing the Japan Sea to the north, and the other facing the Pacific Ocean to the south. The urbanized Osaka plain extends northeast to Kyoto, and through the Izumi Range to Wakayama prefecture to the south. This dramatic terrestrial landform is at the intersection of the Eurasian and Philippine Sea tectonic plates. While elaborate train and highway links interconnect the nearly 24000,000 people who live in Kansai, this blog post focuses on a score of local hikes by an interdisciplinary team of researchers exploring the intersection of geological and human land formations in search of both cultural heritage and ecologically sustainable practices in the face of climate change.

Our peripatetic method began over two decades ago when we explored the rapid urbanization across the vast area of Bangkok’s Chao Phraya Delta, “tasting the periphery” via walks along stops at farms along the newly constructed outer ring road. In our method, close-up observations of agricultural and urban landscape practices are compared with remote sensing data and historical imagery. We later came together over a decade ago to examine the construction of flood protection walls by the Japan International Cooperation Agency around industrial estates north of Bangkok. In 2011, Thailand experienced the most economically damaging flood in its history and Japan suffered from the Tōhoku earthquake and Tsunami, while one year later Superstorm Sandy crippled the New York City region. Our conversations and perspectives are enriched by both our countries of origin ― Japan, Thailand, and the United States ― and informed by our disciplinary training ― architecture, landscape architecture, and landscape ecology. Our Kansai walks explore urban and rural transformations as part of The Landscape Ecology Lab at Wakayama University at a time of the construction of enormous and unprecedented flood prevention infrastructure in all of our hometowns.

This diary of our conversational walks around Kansai is structured around three theoretical futures that emerged from the long-term urban ecological research of the Baltimore Ecosystem Study. These theories are applied to a period of rapid change in the landform of Japan in response to both the aftershocks of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, and the present reality of a shrinking and aging national population. First, our walks encompass the urban megaregion of Kansai which is seen as an agglomeration of cities and villages around and within agricultural and wild areas tied together by vast transportation and virtual communications networks. Secondly, our paths trace an urban/rural continuum of entangled lands and lives in rural and wild places that have both biophysical and cultural features, called “satoyama” in Japan. The urban/rural continuum of satoyama combines terrestrial, non-human, and human artifacts and the various processes interacting within a dynamic heterogeneity of urban change. Finally, we employ metacity theory to understand embodied places and livelihoods within shifting spatial matrices of biophysical, social, and political structures. A metacity approach provides a way to visualize and project urban structures and transformational processes across space and through time akin to the metacommunity, metapopulation, and metastability frameworks in ecology.

Kansai Megaregion: Walking along the Median Tectonic Line

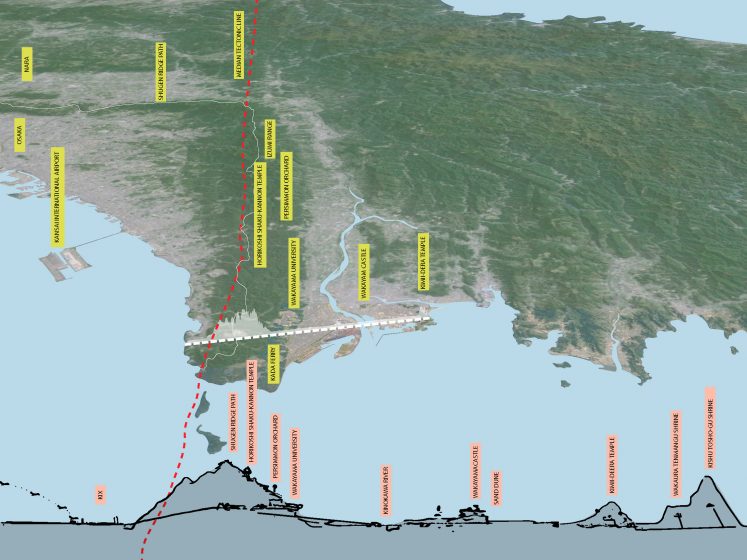

Our drives, train trips, and walks took us from Osaka Bay to terraced mountain farms and back again to sea-level fishing villages, sprawling urban plains, and river basins. These embodied experiences pass between arduous hikes up tectonic terrain, slow strolls along landforms shaped by human hands, and the speed convenience of the modern rail and road transportation landforms of the anthropocene. Kansai Airport terminal, with its delicate wave-like roof, was designed by Italian architect Renzo Piano, sits on a 4 x 2.5 km artificial island in Osaka Bay. The Bay is an oval-shaped inland sea between the Kii Mountain Range facing the Pacific to the south and the Chūgoku Mountain Range along the Japan Sea to the north. The airport is connected to Japan’s Honshu Island, the 7th largest and most populous in the world, by the 3.75 km Sky Gate Bridge. While most travelers continued by car or train north to Greater Osaka, the Nankai Railroad leads to the seaside of Wakayama Prefecture to the south. Since 1903, the train line has tunneled through the 1000-meter-high Izumi Range, which forms a huge historical and scenic “central park” for the Kansai Megaregion. The Isumi range follows the Japan Median Tectonic Line, where the ancient Nankaido traces a walking path along the ridge line across the mouth of Osaka Bay from Shikoku Island to the 8th-century imperial capital of Nara to the east.

After tunneling through the mountain range, we disembark at Wakayama Daigaku Mae Station, located near Wakayama University, founded in 1949. National Highway 26, connecting Osaka to Wakayama, was completed in 1952. The Keinawa Expressway now loops around the southern and eastern slopes of the Izumi Ridge, directly connecting Wakayama City to Nara and Kyoto. The post-war modern campus occupies a large land-scraped plain on the south-facing slope of the Izumi Range, overlooking the Edo-period castle town of Wakayama at the mouth of the Kinokawa River. Wakayama Daigaku Mae Station was completed in 2012 and is connected to a large new shopping mall and suburban residential enclave, circling the university campus on three sides. While the campus maintains a brutalist concrete and glass architectural style, both the subdivision and the station have a vaguely Tuscan hill town feel, which is complemented by an Italianate wedding chapel. The local bus brings us from Daigaku Mae Station to Green Planet House just outside the west University gate.

Wakayama University is the only national university within mostly rural Wakayama Prefecture. According to the university website, its post-war modernist, geo-engineered campus is situated in “a place cultivated over time in a setting of abundant historical and natural resources”. This forest setting, removed from the city below, is meant to educate “the next generation of students who will be the driving forces of regional revitalization”. In spite of the convenience of the new train station, the campus is the product of American car-based planning, fenced and ringed by faculty and staff parking lots, while most students commute by train and bus from south Osaka. However, the University’s Landscape Ecology Lab monitors the fences around the campus with nighttime cameras, capturing the many non-human visitors from the surrounding forest inhabiting the Izumi Range. The most recent seismic activity along the south edge of the Izumi Mountains was in the 7th to 9th century, but earthquakes remain a risk today.

Historically, the ancient Nankaidō walkway extends along the entire Isumi ridge line, crossing the sea from Shikoku Island to the old imperial capital of Nara. It was established during the Asuka period (593–710 C.E.) with the introduction of Buddhism and written language from China and Korea. Several modern north/south highways tunnel through the ridge, providing quick points to rural roads that give access to agrotourism and app-assisted hiking routes that trace its history and scenery. The difficult mountainous landform trail is the birthplace of an ascetic shamanism that incorporates Shinto and Buddhist concepts founded by En no Gyoja. The Nankaidō trail is marked by 28 sutra mounds that mark a pilgrimage practice between the mounds called Katsuragi Shugendo.

After a deep sleep and breakfast at Green Planet House, our trusted colleague Dr. Masanobu Taniguchi expertly drove us up the winding narrow roads to Horikoshi Shaku-kannon temple, one of the pilgrimage stations, now also serving agro-tourists, trekkers, motorcyclists, and environmental scholars like ourselves. The road winds through centuries-old persimmon or “kaki” orchards. In contrast to the tectonic land formation of the mountain ridge, the Nankaidō and the ancient terracing of the foothills are both the handiwork of countless laborers over centuries. Colorful garlands of drying fruit hang along the roadside, while miniature trucks take the precious fruit downhill to markets. In spite of considerable efforts to maintain these ancient fields with agrotourism and logistical infrastructure, our hosts noted a considerable decline in the number of fruit garlands lining the route this year.

Our trip culminated at Horikoshi Shaku-kannon Temple, an ancient pilgrimage stop and training hall for Yamabushi mountain priests. Located at an altitude of 664m at the foot of Mt. Tomyo (857m), the temple porch overlooks slopes terraced by hand down to the Kinokawa River. A friendly monk greeted us with fresh persimmons and a tour of his house, recently re-thatched with a new straw roof. The day ended with a warm ramen soup at a farmstand along the new National Expressway, E480, the newest highway tunneling under the Izumi Mountains. At Kushigaki no Sato, products from the Katsuragi orchards are sold along with fresh fish from the Osaka Sano Fishing Port, on the other side of Kansai Airport. Urban infrastructure has put mountainside orchards and seaside fishing villages within easy reach of cars. The newly constructed expressway connecting Osaka to Wakayama is just one example of the enormous land formation processes of the anthropocene, while not at the scale of plate tectonics, it impacts an area well beyond the handmade trails, orchards, and rice terraces above.

The following day we continued to follow the Median Tectonic Line across the mouth of Osaka Bay to Tomogashima Island, the forested home of another Shugen pilgrimage site, as well as the setting for numerous Meiji-era military forts protecting the harbor. We took the Nankai line from Wakayama Daigaku Mae to Kada station. Departing by ferry from the pier at Koda fishing village, we were joined by trekkers, military site-seers, and those looking to catch, and the case with a group of college students, cooking and eating their catch. Kada port is protected from tsunamis by new sea walls, but just above the village, Awashima Shrine has historically served as a tsunami refuge. Here, hundreds of dolls line the porches, to be offered in the Shinto ritual of Hina-nagashi on boats offered to the sea.

One appreciates the power of tectonic land formations hiking along the tectonic line at the center of the Kansai megaregion. The 28 sutra mounds, forest trails, shrines, villages, temples, and fruit orchards comprise a historical and scenic park for the urban agglomeration of 20 million people. It is a landform that resulted from millennia of geological history in the making, but also over 1400 years of human handiwork, now connected through a century of grading land for rail travel, and decades of bulldozing for a sprawling car-based urban megaregion.

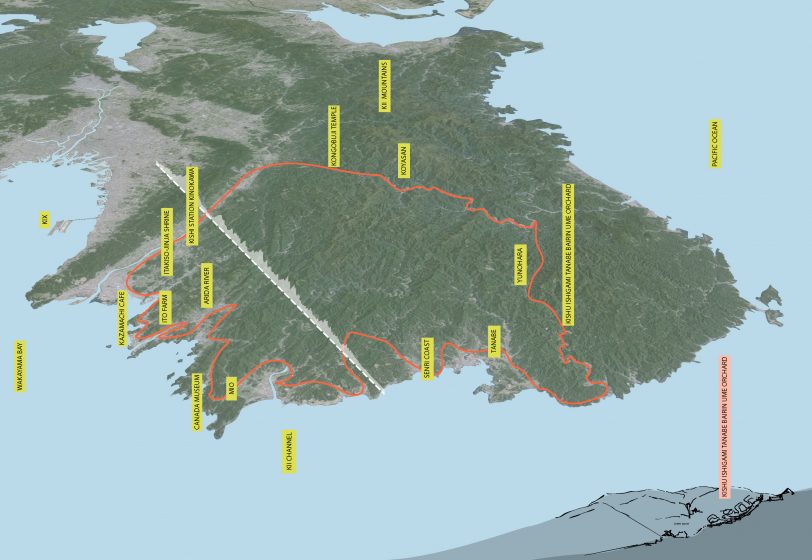

Wakayama Satoyama: Exploring an urban/rural continuum

Wakayama Prefecture consists of 80% mountainous terrain. While the prefecture is 60% forest, it also ranks first in Japan in the production of oranges, persimmon (kaki) and apricots (ume). Our walks in Wakayama extensively covered an urban/rural continuum from the old Edo city situated in the historically bountiful rice-growing village areas in its river basins, but also up the southern mountainside orange and apricot growing villages to the Pacific Ocean. 70% of Wakayama City was destroyed by waves of American B-29 bombers overnight on July 9-10, 1945. While much of the Edo-era castle canal-based town plan remains intact, the city has only partially filled its old fabric, with many vacant buildings and hundreds of surface parking lots. Most people choose to raise families outside the city, and the river basin wet paddy rice fields likewise are pitted with new housing subdivisions of landfill. The prefecture’s dense transportation networks constitute an urban/rural continuum of forests, grasslands, streams, ponds, orchids, rice paddy, historical settlements, new suburban subdivisions, and small parking lots everywhere within what has historically been defined as “satoyama” in Japan.

Our first walks in the city followed various canal embankments between Wakayamashi to Wakayama train stations. Neither the city museum nor the rebuilt castle that dominates the center of town betray the tragic history of the night in 1945 when American B-29 bombers rained down incendiary bombs. However, on the 70th anniversary of the bombing, the trauma of that night was remembered.

“Wakayama Castle was burnt down by the constant waves of attacks, and 70% of the city was reduced to ashes overnight. More than 1,400 people died, and 27,402 homes in the city were completely destroyed.”

The mixed-use network of homes and workshops of the pre-modern Edo city ended up leading to the city’s destruction. As the Wikipedia site on the air raids on Japan explains: “Initial attempts to target industrial facilities using high-altitude daylight ‘precision bombing’ were largely ineffective. From February 1945, the bombers switched to low-altitude night firebombing against urban areas as much of the manufacturing process was carried out in small workshops and private homes: this approach resulted in large-scale urban damage and high civilian casualties.”

While the town’s wooden buildings caused a great inferno following the bombing, the Edo-era urban landform persists. The formidable castle stone walls were built atop a sea-facing sand dune, and a canal system diverts mountain-fed rivers through the town, once the site of all merchant activity. Now incomplete and car-dominated, only post-war buildings dot the old Edo city grid. The town seems mostly populated by the elderly, school children, with some commuting workers. But moving from the Green Planet House on the hill to a guest house in town, one can take pleasure in many residents who choose to stay in the city as well as small restaurants, new and old. Efforts to bring life back to the canals include the new Kyobashi-Shinsui Park.

From Wakayama JR Station, the Wakayama Electric Railway Kishigawa Line travels 14.3km to Kishi Station in neighboring Kinokawa City, where a cat is the legendary station master. The antique-themed rail cars literally strike a transect along a patchy urban/rural landform passing lower rice fields, canals and villages and modern raised subdivisions and roadways. Among the 14 stops, we get off to pay respects to “Itakeru no Mikoto”, who is known as a god of afforestation, who traveled around Japan planting trees. The Itakiso-Jinja shrine, located in a beautiful cedar (sugi) forest is sacred to those involved in the timber industry who visit from all over the country. The shrine is the built embodiment of the nature/culture continuum of Shintoism.

Other train and bus lines connect south to fishing villages and beaches tucked under sea-facing hilltop temples and shrines. Founded by a Tang Dynasty monk in the 8th century, Kimiidera is a Buddhist Temple approached by a street of shops leading under a gateway, up 231 stairs to a terrace overlooking Wakanoura Bay ― known as the Bay of Poetry ― and south to the city of Kainan. Wakaura Tenmangu Shrine and Kishu Tosho-gu Shrine also face the same Bay, accessed by even longer stairway hikes up the foothills of the Kii mountains to the south. Again, these hand-sculpted highland sanctuaries provide tsunami refuge to the populated seaside below.

The Kii Mountains and the Pacific Ocean beckon us as we seek out the bountiful mountainside terraced orange groves and seaside fishing villages with our new guide, Dr. Yuki Sampei from Kyoto Sangyo University. Our van first brought us to the mountain-terraced orange groves of Ropponju no Oka, the birthplace of mandarin oranges. overlooking the Arida River valley south of Kanain. Japanese mikan and Japanese sweet are types of satsuma or mandarin orange. Cultural heritage designation is a strategy employed by the Landscape Ecology Lab to maintain these important historical agroindustries. One example is the Japanese apricot (ume) growing land-use system, called the Mibe-tanabe ume system. Our visit included the Kishu Ishigami Tanabe Bairin Ume Orchard which has achieved a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage designation with the Food and Agricultural Organization of the UN.

Oranges were still being harvested by hand, packed in crates, and carried by single-rail mechanical beltways up the steep hillsides. Returning to Arida City, a logistical hub for this prized fruit and its by-products, we visited orange factories, wholesalers, and retailers. One such business dating from the Meji era (1868–1912) is Ito Farm, specializing in Arida mandarin oranges and citrus products such as juices and sweets. While the sanitary part of juice making is indoors behind windows, the shipping and sorting of the 13 types of citruses ― including Satsuma mandarin orange, ponkan, kiyomi, iyokan, and hassaku takes place in public view as forklifts cross back and forth between open-air warehouses linking both sides of the road. The farm store occupies an old orange storehouse.

Again, we follow recreational motorcyclists to a tiny fishing village just north of Arida. Kazamachi (meaning “waiting for good wind for ships”) Cafe is tucked in a small port protected behind a peninsula and tsunami protection facing the Kii Channel to the west. The bay expands out to Shimotsu town with its JR train station just south of the mouth of the Kamo River. We had a long wait while the motorcyclists had their fill of fresh fish, but it gave us a chance to walk around this tiny vulnerable, mostly abandoned fishing village. These villages, which before the rail lines and highways were difficult to access, are now within easy reach for Kansai megaregion scenery and food lovers. Yet an aging population and the anxiety following the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami have depleted the residential population.

Oranges and fish meet in the roadside station along the new north/south highway connecting Osaka to the Senri coast. Five nearby ports provide fresh fish, in addition to the produce from the “Fruit Kingdom of Wakayama”. On our way to the Senri coast, our next stop was the previously remote town of Mio, which is situated facing the Pacific Ocean at the mouth of Wakayama Bay. Most able-bodied people emigrated to Canada for the fishing industry, and the Canada Museum sits in the mostly empty seaside town as a testament to Japanese emigration. Some farmers’ markets along the new highway are run by agricultural corporations. Kitera Akitsuno Direct Sales Office is a social business corporation founded in April 1999 by local volunteers. Community development, investment, business planning, and operation are run by Kamiakitsu area residents and their support groups. These rest stops are contact zones in the urban/rural continuum directly connecting urban customers to farmers and fishermen.

After our coastal hugging route of walks in fishing villages and hillside fruit orchards, we headed back to Wakayama City by going directly north through the mountains, passing through landslides along the geologic seam between volcanic and marine sediment. High above Tanabe City, we enjoyed a homestead lunch at Ryunohara a farmstay guest house being meticulously restored by a native Singaporean. With an active social media presence, Ryunohara attracts volunteers and guests from around the world to get a taste of the rewards of hard manual labor in rural Japan. The trip culminates near the mountain peak of Koyasan, and the zen gardens of Kongobuji Temple, the head temple of Shingon Buddhism, the sect introduced to Japan by Kobo Daishi in 805. While the van covered much more distance than we could ever have reached by foot, it was the walks at each stop where our feet could feel the intersection of the geological infrastructural and human hand in land formation that constitutes Wakayama satoyama as an urban/rural continuum.

Kansai Metacity

Our stop at Ryuohara indicates the importance of digital communication infrastructure in connecting people and places, not just at a mega-regional or prefectorate scale, but also globally. We will conclude this blog with a description of the traditional art of Imperial landform making in Kyoto before concluding with three examples of locally rooted contemporary landform activism that reach out to global conversations on equity and sustainability in Kyoto, Osaka, and back in Wakayama. Like in Ryuohara, we visited urban refugees from Japan and from around the world who became traditional foresters, farmers, traditional house restorers, and craftspeople.

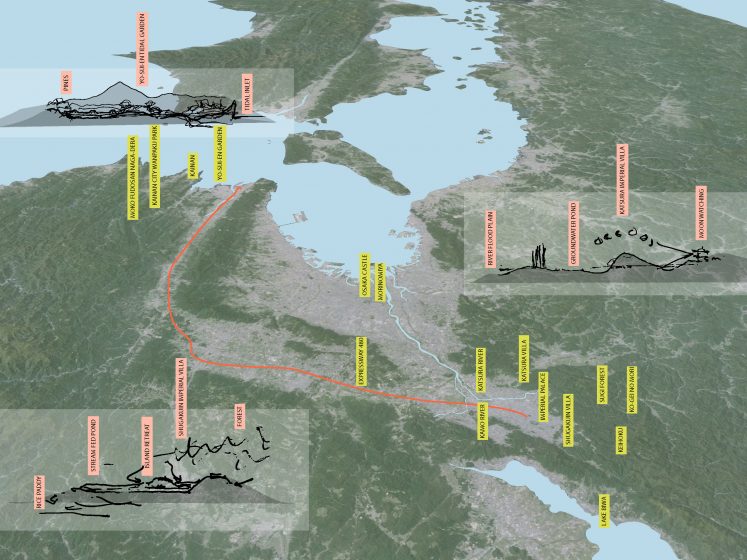

Unlike the mercantile sea-facing cities of Osaka and Wakayama, Kyoto is, geographically, a headwater city chosen as the seat of the imperial court of Japan in 794. The city’s Chinese-influenced feng shui planning proved to be politically auspicious and naturally bountiful as it served as the imperial capital of Japan for 11 centuries. The city was spared from the firebombings that leveled Osaka and Wakayama. A great deal of cultural heritage has been preserved, and the city continues to be a vibrant metropolis today. Kyoto is surrounded by mountains on three sides with Lake Biwa, Japan’s largest freshwater lake to the northeast. The city and the imperial palace face south on top of a large natural freshwater table in between two tributaries of the Yamashiro Basin. This large natural water table provides Kyoto with ample freshwater garden pools and wells. Due to large-scale urbanization, the amount of rain draining into the table is dwindling and wells across the area are drying at an increasing rate.

If one traces a transect from the Shugakuin Imperial Villa in the northeast foothills above the city to Katsura Imperial Villa, in the river floodplain to the southwest, it would cross directly through the imperial palace regally situated in the middle. The landform of the two villas, together with the earthworks which direct river headwaters through the Kyoto city itself, demonstrate the traditional art of Kansai landforms and waterscapes. Our garden walkarounds began at the scholar retreat of Shugakuin, where an artificial lake is formed at a natural spring headwater. An artificial pond, sculpted like the rice-feeding retention ponds below, is the setting for an island writing retreat and a lakeside tea house for a retired emperor. We can follow the water down to the Kamo River, past the imperial palace, and through the more popular quarters of the city, where it is a pleasurable natural resource in the center of the city.

Kyoto’s city builders straightened the Kamo River through the gridded town but gave it ample room to swell with seasonal rains and snow melt. Our walks next take us to Katsura Imperial Villa, situated in the floodplain of the Katsura River southwest of the city. A sculpted groundwater-fed pond is at the center of a scenic garden of rolling artificial hills with walking paths to enjoy the seasonal change. It is a classic example of landform art by cut and fill; when the ponds were dug, they provided earth for the hills. From the verandas of the main house, raised above the river backwater floods, guests watched the moon reflected in the hand-sculpted pond. Remarkably, Expressway 480 connects back to Wakayama where a third type of landform waterscape ― the seaside tidal water garden at Yo-sui-en ― provides a tea house near an ecological hotspot for marine species and waterfowl.

In contrast to our imperial and aristocratic water garden landform walks in Kyoto, we hiked back up the Katsura River led by Dr. Atsuro Morita from Osaka University to trace the path of lumber from the sugi cedar forest up the mountains to the north to the Nishi-takasegawa canal and warehouses behind Kyoto’s Nijō Castle. In the cedar forest of the mountainous region of Keihoku, we were greeted by Sachiko Takamuro, founder of Ko-gei no Mori, the Forest of Craft. “Kogei-no-Mori focuses on the fact that nature is the starting point for manufacturing and aims to rebuild a healthy relationship between people and nature through action-based manufacturing”. We ate fresh sushi from the nearby Japan Sea prepared by the village grannies, and saw the wood-veneered surfboards, employing traditional Japanese crafts such as urushi lacquer.

Back in Kyoto, our growing team met at FabCafe with Nami Urano at Loftwork to discuss another urban ecosystem initiative in Osaka. Loftwork brought us to be part of a creative walk to inspire urban ecosystem design in the Morinomiya redevelopment area behind Osaka Castle. The walk provided an opportunity to informally exchange opinions about the possibility of ecologically conscious design in Morinomiya, while actually walking along the canal and riverside around Morinomiya with those involved in the area development. Again, the peripatetic method brought to light many possible relationships between the city and nature in the Morinomiya area and how to “bring out the charm of the land” through embodied experience.

Returning to Wakayama, our last walks were in the satoyama outside Kainan City. Coastal Kainan is particularly vulnerable to tsunamis, so the city hall was recently relocated up to former farmland in the foothills. The new Kainan City Wanpaku Park was designed around old agricultural ponds, managed by Biotope Moko (孟子), named for a fourth-century BCE Chinese thinker in the Confucian tradition. Unfortunately, this contract at Wanpaku Park ended with filling the old ponds due to renovation for tsunami evacuations in 2024. Nevertheless, Biotope Moko is still continuously providing local environmental education programs and various nature classes for local kids and adults and promoting organic rice and soba farming.

Biopte Moko’s Biodiversity Revitalization Project seeks to restore the biodiversity of the satoyama environment. With an aging agricultural working population, many rice fields and irrigation systems have been abandoned and upland forest areas are no longer managed through thinning. The forest temple of the Moko Fudosan Naga-dera is hidden in the hills northeast of Kainan at the headwater of a satoyama irrigation stream. The temple, founded in 815, had become overgrown and inaccessible. In 1998, the founder of Biotope Moko, Toshihide Kitahara, organized a team to make the temple accessible again and excavated dragonfly ponds in the former rice paddy with the cooperation of the local landowners. In 2009, the original restoration place of Biotope Moko was designated as a future heritage site by UNESCO Japan.

This blog post collapses the scales of a vast urban megaregion with a dragonfly pond in order to promote metacity theory as a way to simultaneously engage with landforms as cultural heritage and sustainable ecology. As mentioned above, metapopulation theory suggests that species survival is dependent on dispersal, metacommunity theory states that a set of local communities are linked by the dispersal of multiple interacting species, and metastability theory proposes that native species communities can form patches that delay the extinction processes by mutual cooperation. Metacity thinking along a dispersed urban/rural continuum may assist in localized human and non-human species cooperation and survival in the face of the huge infrastructural changes being built in the wake of climate change.

Huge infrastructure projects are currently sealing sea and waterfronts in Kansai, Bangkok, and New York in response to disasters that took place over a decade ago. In order to imagine the cooperation networks we need to create a shift from coarse grain technologically driven large-scale landform policies to multiscalar ecological designs that require new tools of local knowledge production linked to broad communication networks. In addition to our walks and talks, we sketch, survey, interview, photograph, and launch drone cameras in order to publicly elevate such finer-scale efforts. Our drone images harken to early 20th-century birds-eye views of cities and scenery newly accessible through modern railroads by Hatsusaburō Yoshida, and the fukinuki yatai ― “roof blown off” views show how urban life extends inside and out. Contemporary representational tools rely on a rich tradition of spatial anthropology (Hidenobu Jinnai) and ethno-graphics (Wajiro Kon) in Japan. Our illustrations in this blog post point to the importance not only of walking but of hand-making future landform projects collectively.

Walking is both thought-provoking and a form of embodied knowledge creation. Dispersed walks in the water gardens of Shugakuin, Katsura, and Yo-sui-en provide inspiration for the integration of design and ecological science in the face of the challenges of climate transition. Landform activism in Kansai continues to be both cultural heritage as well as sustainable ecology by a set of interlinked human and non-human communities. Walking with activists in the forests above Kyoto, the urban canals of Osaka and Wakayama, and throughout the Kansai megaregion gives us great hope in our ability to thrive in an insatiable and unpredictable future.

about the writer

Yuji Hara

Yuji Hara is an associate professor at the Faculty of Systems Engineering, Wakayama University, Japan. He specializes in landscape planning and anthropogenic geomorphology and conducts field research in Wakayama, Osaka, Bangkok, Chiang Mai, Metro Manila and other Asian cities as well as in the Netherlands and around New York.

about the writer

Danai Thaitakoo

Danai Thaitakoo is an adjunct lecturer at the School of Architecture and Design, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, Bangkok, Thailand. His interests lie in the field of landscape and urban ecology with an emphasis on landscape changes, urbanization, landscape dynamics and hydro-ecology.

Yuji Hara, Brian McGrath, and Danai Thaitakoo

Wakayama, New York, Bangkok

Add a Comment

Join our conversation