The rich, air-conditioned planet deserves to be mocked by climate activities. Rather than gluing themselves to random famous paintings, it might be more appropriate to start shaming stores running air conditioning on high, while leaving their doors open to the street. Or protesting the artificial snow at Dubai’s indoor ski slopes. These actions would target for ridicule those whose actions are directly connected to climate inequality.

India is roasting, with some cities like Delhi pushing to almost 50 degrees C (122 degrees F). In India’s recent election, at least 33 poll workers died while doing mostly compulsory work to administer the election in sweltering polling places. All told, there have probably been thousands or tens of thousands of people who have died in the heat wave, as measured by epidemiologists who look at the number of excess deaths above the usual background mortality rate. What breaks my heart most about these deaths is the separate, unequal planets of humanity with regard to urban heat. No one needs to die during a heat wave. There is a clear cause of mortality: a lack of ways to cool the air, at least in emergency cooling centers, and a lack of adequate medical care for those who cannot get there and are vulnerable, often the elderly or those with pre-existing conditions. Or those, like the Indian poll workers, who must work through the brutal heat. Cities in the developing world, which will face the highest absolute temperatures, will have the least economic capacity to cope.

In contrast, citizens of the richest countries live on another planet. There are still climate-change-induced heat waves in those cities of course, and indeed the largest increases in summer temperatures from climate change are often forecast for high-latitude cities in developed countries. However, higher availability of air conditioning and better medical systems help residents of the rich, cool planet. Heat action planning on this planet is still essential, but focuses on protecting outdoor workers or planning for overloaded electrical grids from high demand during heat waves, as residents crank the air conditioning. On this rich, cool planet, the death rate during an equivalently severe heat wave might be one-tenth or less of what it is in India.

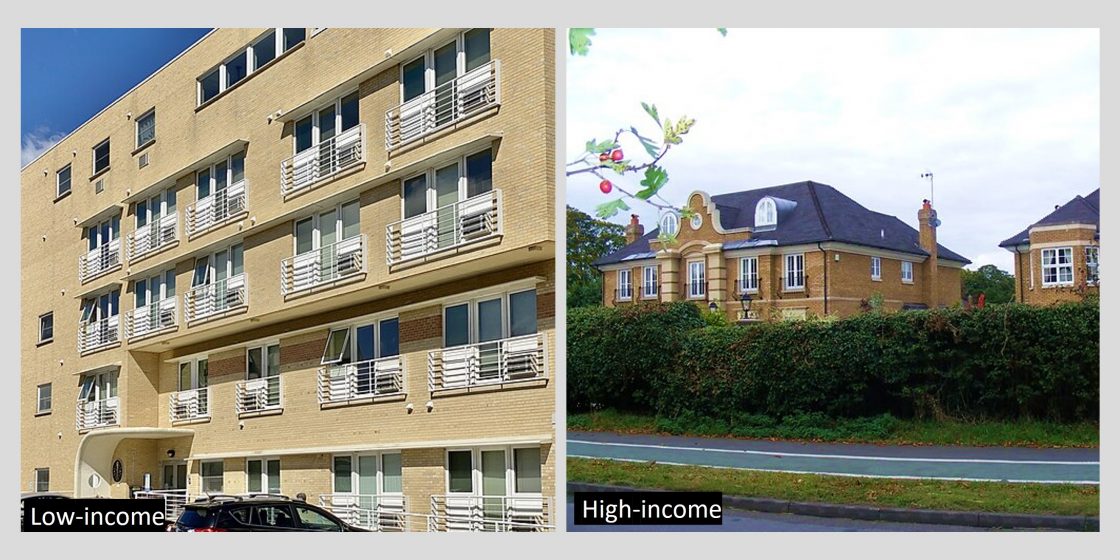

I think a lot about urban trees, as one way to cool outdoor air temperatures. A row of street trees, as they shade impervious surfaces and transpire water, might reduce nearby air temperatures by 2 degrees C or more. And yet, those living on this poorer, hotter planet generally have less tree cover than those living in developed countries. Cities in developing countries tend to be denser, and so have less space for trees, and their governments have fewer financial resources to spend on tree planting and maintenance. But these are precisely the cities that need tree cover more since they are more vulnerable to climate change. In comparison, tree cover on the rich, cool planet—while still important for community health—is relatively less essential for survival, simply because of the greater penetration of air conditioning. And yet, this is the planet with cities with greater tree cover!

Right: Executive homes, Station Road, Tring. Credit: David Sands

This inequality, this story of two different worlds, also can be found within cities. My own research has focused on the United States, looking at a large sample of almost 6000 communities across the country. In 93% of American cities, poor neighborhoods have less tree cover than rich neighborhoods, on average 15% less tree cover. This inequality extends to neighborhoods that are predominantly the home of people of color (POC). In a recent paper, my colleagues and I found that every year, there are 190 more deaths annually and 30,000 more people made ill annually in POC neighborhoods than would be if they simply had the tree cover of equivalently dense non-Hispanic white neighborhoods. Similarly, POC neighborhoods consume 1.4 Terawatt-hours more electricity simply because of this tree gap.

If we turn our attention to the future, to adapting to climate change, we find that the neighborhoods that don’t have enough tree cover now, which are often poorer and predominately POC with a high population density, are those with the highest return on investment of tree planting. In these denser neighborhoods, the costs of tree planting are generally outweighed by the health benefits during heat waves, let alone the other benefits that trees provide. This is less of the case for suburbs, often richer and predominately non-Hispanic white, where the lower population density means each tree benefits fewer people during heat waves. In other words, the neighborhoods most in need of trees, where nature-based solutions to heat are most viable, are the ones with the least political power in the United States. Sadly, municipal tree planting and maintenance efforts (and certainly those on private lands) sometimes follow patterns of money and power, to neighborhoods that need the trees less.

Heat will likely be the deadliest manifestation of climate change in the coming decades. Heat already kills more than 356,000 people per year, more than any other weather-related factor. By 2100, 48-76% of humanity will be exposed to extreme heat every summer. But the people most in power globally economically and politically, who could most help push through substantive climate mitigation (avoiding the worst extremes of climate change) and climate adaptation (preparing for the coming warmer world), live in a bubble. Residents of the rich, cool world (and I am also speaking about myself here) live in a bubble of cool, artificial areas. Many of us work on a laptop from home or in a white-color office that is similarly air-conditioned. The lived experience of an Indian poll worker, or, for that matter, that of a US construction worker, is often missing from the consciousness of those of us who live on the rich, cool planet.

We must start bridging these two worlds. We need universal access to cool air for all, at least during emergencies when it is a matter of life and death. This implies an increase in air conditioning capacity, which will need to be energy efficient to avoid a huge increase in electricity consumption and the greenhouse gas emissions that would go along with it. This is the core of the Global Cooling Pledge, which promises to reduce cooling-related emissions by 68%, significantly increase access to sustainable cooling, and increase the average efficiency of new air conditioners by 50%. We also of course need to increase tree canopy cover, increasing it in the neighborhoods that need it most, whether in developing or developed countries.

We also need to somehow improve communication between the two planets. There is a place for good reporting or filmmaking here, art that captures the crushing experience of heat on the poor, hot planet. The rich, cool planet (of which again, I admit I am a resident) deserves to be mocked by climate activities. Rather than gluing themselves to random famous paintings, it might be more appropriate to start shaming stores running air conditioning on high, while leaving their doors open to the street, their cool air wastefully flowing out. Or protesting the artificial snow at Dubai’s indoor ski slopes. These actions would at least target for ridicule those whose actions are directly connected to climate inequality, in our separate and unequal two planets of urban heat.

Rob McDonald

Basel

Leave a Reply