Could we change the outcomes for trees by changing the politics around trees? A network of neighborhood-based citizen foresters could help with this educational mission and could also help with this. Every neighborhood could have a designated (or self-appointed) tree steward or resident forester who is trained and knowledgeable about the health of trees.

I have come to believe that in the fight to save trees and forests in our cities, it is necessary to better understand what I am calling the “psychology of trees”, those factors and influences and patterns of thinking that affect the decisions individuals, developers, and even entire communities, make about protecting (or not) the trees and forests around them. Pulling apart and better understanding this tree psychology will in turn allow us to craft protection strategies that work and, more importantly, are embraced and acceptable to those making decisions.

Not long ago, I was invited to present my work and ideas to a brown bag lunch series in the Psychology Department here at my home institution, the University of Virginia (UVA). It was an interesting event and one of the first times I had the chance to talk about this issue with professionals and scholars in the field of psychology. It further reinforced my sense of the importance of psychology, and I came away with a few especially useful insights and pointed suggestions.

Give a tree a voice

One comment and response had to do with the personhood of trees, something I had already been thinking a lot about. One younger psychology faculty member related the story of her child who had decided to become a vegetarian and as she explained this “She doesn’t feel comfortable eating something that has a voice”. We do indeed seem to make a sharp psychological distinction between animals (that do clearly have voices) and plants and trees (which most of us feel do not).

Could we change the psychology of trees by somehow giving them a voice, something that humans equate with personhood? As more is being discovered about the biology of trees and forests there are strong arguments made that make distinctions between trees and birds less clear or valid. Trees certainly generate many sounds that derive from their biology and their life functions. But perhaps we can amplify sounds that could be unique “voices” that trees and forests already have.

Saving a forest may in a very real sense come down to publicizing and amplifying the many audible voices of the many species that occupy and depend on that habitat: the wood thrush, the eastern tree frog, the crickets and katydids, and cicadas that emerge each summer where I live and that collectively speak (and sing) to us in the eastern US. Joan Maloof, founder of the Old Growth Forest Network, in her excellent book Nature’s Temples speaks compellingly of how special and distinct an older forest is: its remarkable diversity of leaf-eating insects, she says, means the forest literally “sings with their songs.”[1] …

There are now several startup companies that are beginning to develop research aimed at collecting and interpreting the complex electrical and biological signals trees send in response to stressors like drought and heat. A Swiss company called Vivent Biosignals, for example, is already developing commercial products that they refer to as plant electrophysiology. “Plants are talking, we let you listen in,” is the catchy tagline one sees on the opening page of their website.[2] Their “wearable sensors” hold the potential to give trees a voice of some kind: whether it is something audible, or more like an amplifier needle or a Geiger counter needle that moves in response to a tree-generated signal of some kind, is not clear. Perhaps the voice takes the form of a text message sent by a tree, pleading for water or for help in fighting a pest or disease.

The more of these kinds of biosignals we collect and seek to “listen to”, the more the psychology around trees will change. We begin to better appreciate their complex biology in this way and may be better able to evaluate what we need to do to protect them, in addition to stopping someone from cutting them down.

And amplifying the voice is perhaps part of a larger psychological strategy of emphasizing the intrinsic similarity between trees and animals—we know increasingly that trees are not passive, but move in many ways and are quite active, for example, and that they sway and move and grow, and that change shapes as water is moved and stored over the course of a day. It is difficult to see a tree as passive and immobile in light of how a tree moves and changes even just over the course of a day.[3]

Neighborhood norms

A second comment from that day with my Psychology Department colleagues had to do with the importance of norms and the idea that decisions about trees and forests might be tied to or built upon established norms that exist broadly in society. Our discussion of norms that day was rather abstract but it set in motion my own search for established norms that could be helpful in shifting the psychology of how we see trees.

A norm can be defined as “the unwritten rules shared by members of the same group or society” and they can emerge and be sustained in many different ways.[4] The precise set of social norms we carry with us and that influence our actions and behavior will vary of course by culture and geography and there may not be a clear or precise list of these norms to refer to―but I think it a promising suggestion in the effort to protect trees and forests in cities we seek wherever we can to build onto our existing set of norms.

One possible norm to build on might be the idea of what it means to be a good neighbor. Arguably this is an atrophied norm, a norm in need of refurbishment. When we begin to see that one’s decision to clear cut the trees in the front yard yields clear and serious negative impacts on our neighbors―e.g., trees that provided shading and cooling benefits are gone, runoff that was captured by the trees flows onto one’s neighborhood property removing trees seems to violate a norm of neighborliness.

I have started in my own neighborhood to try to change the psychology of trees a little bit in this way. Complimenting my neighbors on the beauty or majesty of the large trees on their property at once seems to be appreciated by neighbors but also a bit surprising to them (as if it rarely or never happens). Doing this reinforces the impression or the psychology that one’s choice to cut down trees will be perceived negatively by one’s neighbors and will make that bad outcome less likely. If my neighbor thinks I care about that tree, that I enjoy seeing it, that I think it is beautiful, and that it provides an element of emotional uplift when I pass by it, s/he will be less inclined to treat that tree carelessly.

The psychology of the decision to cut down a tree then shifts markedly from an individual, or mostly individual-regarding one, to one that has larger neighborhood and community implications. It should engender a sense of pride even in the owner of the tree and perhaps over time this will happen.

Short of talking individually to each neighbor about their trees―a labor-intensive undertaking to be sure―and one that relies on serendipitous interactions on walks and casual chance encounters, are there other techniques or tools that could be used to foster or strengthen this sense of the collective nature of tree decisions? And the idea that, by protecting your trees, this is one important way to be a good neighbor?

What else could be done to strengthen or activate the norm of neighborliness on behalf of trees? I’m not aware of any place where this has been done exactly but preparing (and distributing) a neighborhood-scale map of trees and forests there would help solidify the collective sense of the value of trees and perhaps reinforce the sense that cutting down a tree (on our collectively embraced map of our neighborhood forest) would be tantamount to being a very bad neighbor indeed. Many cities now have extensive online tree maps (and databases), like the one managed by New York City, and these can be important tools for raising awareness about neighborhood trees and help to cultivate a sense that one’s home (and trees) sit within a larger neighborhood forest to which all have some duty of care or protection.[5]

But it may be more about changing our mental maps of our neighborhood―seeing the trees and forests around us is an essential part of the life and place we call home. A literal map could help, but so could other steps: organizing monthly neighborhood tree walks, for example, or establishing places in the neighborhood to gather under large trees, and generally finding ways to work the trees and forests into the collective narrative and life of the neighborhood.

The biggest trees in a neighborhood could, and often do, serve as informal gathering spots and it would be useful to start strengthening the importance of place-defining qualities of trees. The grand swaths of shade provided by larger trees could create the scene and setting for at least some of the social life of a neighborhood―there are many events from block parties to adventure play gatherings for families with young children that could happen around and under these trees. In my own neighborhood, almost every street, or street segment, has one or more prominent large trees, most in residents’ front yards. I have dreamed of organizing a schedule of progressive dinners or teas where neighbors meet under a different tree each week. It would be one way of meeting your neighbors, building friendships, and overcoming social isolation; but it would also build up a reservoir of affection for the trees around us.

I have long advocated for the idea of some sort of, for lack of a better way of describing it, ecological owner’s manual, when one moves into a new house or apartment.[6] Perhaps a map of the neighborhood forest, with prominent logos and iconography indicating the species, size, and likely age of at least the most prominent trees, would do much to educate and deepen connections to place and to foster a sense of the collective nature present in an urban neighborhood.

A network of neighborhood-based citizen foresters could help with this educational mission and could also help with this. Every neighborhood could have a designated (or self-appointed) tree steward or resident forester who is trained and knowledgeable about the health of trees and who could also facilitate the idea of living in and collectively managing the neighborhood forest. Such a position, formal or informal, might also serve as a counterweight to the often over-zealous (and sometimes unscrupulous) practice and advice of tree care companies. Maybe the designated neighborhood forester would have to sign off on any permitted tree removal.

In many cities there already exist organizations of tree stewards and green neighbor initiatives that might serve as a useful starting point for this idea.[7]

Another norm to build on is what I have been calling the “safe sidewalk” standard. In many communities, including my own, there is a legal requirement that property owners do certain basic things to ensure the public sidewalks in front of their homes are safe and usable. One specific requirement is that property owners clear the snow from their sidewalks within 24 hours of the end of a snow event. While rarely enforced, it is an interesting rule, maybe really another version or flavor of the norm of neighborliness. Why do we impose such a snow removal expectation but think it is perfectly fine for a property owner to remove a large tree, depriving the public sidewalk of shade and essentially making these unusable in the increasingly intense sun and heat? Perhaps it is a stretch to extend the safe sidewalk rule to the protection of shade trees but there is a certain set of similar norms that could be activated in support of trees and forests.

Still, another norm to build on might be what could be called the legacy norm―that there is an expectation in many societies that one should leave something behind after death and that one should work to leave the community in an improved and better condition. This idea is captured by Erik Erickson’s concept of generativity, or the sixth stage in his theory of social development, something that appears in midlife. It is true that we do many things, take many tangible steps, to affect a more positive future even beyond our own lives. We set funds aside for college, we prepare for retirement, and even our voting behavior can be said at least some of the time to be motivated by a concern for the future. Maybe this is a weak norm (given how few baby boomers have adequately prepared for their retirement) but a norm nonetheless that could be harnessed on behalf of trees and forests. Taking tangible steps to protect trees that will be alive long after we are dead, that will shade and beautify and provide habitat for centuries potentially, could be one of the most meaningful ways to steer or guide this future- or legacy-oriented impulse.

There are many examples of individuals taking steps to protect landscapes (e.g., by granting a conservation easement to an environmental organization like the Nature Conservancy) but these are mostly outside of cities. If this is also an established norm, or a nascent or emerging norm, how could community tree, and city forest protection be built upon? We might need some new legal mechanisms (e.g. a simple urban tree easement or protective covenant) and new entities (e.g., city forest trusts) to enforce or implement them.

Now, admittedly, the norm of neighborliness might at times work against trees, as when your next-door neighbor preemptively cuts down a tree that she fears might eventually fall on her neighbor’s roof. But more generally I think this is a norm that, if more widely acknowledged, would help to protect trees and forests.

I would welcome other ideas about prevailing norms that could be harnessed or guided to protect trees and forests.

Support for “norm drivers”

How to cultivate a new set of tree-conserving norms or strengthen an existing but weak norm can happen in many ways. Legros and Beniamino Cislaghi identify the key role that some people assume as “norm drivers.” I encountered someone I would describe in this way when recently filming a short documentary about trees and tree protection in Atlanta (see the link to the film below). Debra Pearson, a retired Atlanta high school teacher, has created a remarkable backyard forest, and been a special force in advocating for tree protection in her neighborhood. We visited her in the forest and as we were leaving, she told us the story about her next-door neighbor. One day she heard a chainsaw and discovered her neighbors had hired a tree company to cut down a mature white oak tree. She immediately engaged her neighbor, imploring her to stop the cutting, which she did. Such accounts of springing into action to save an imperiled tree are not uncommon, but in this case, its success of the outcome was a function of one neighbor (and friend) approaching another neighbor and advocating for these trees. There are likely many countless ways Pearson’s actions and advocacy have an impact and her views (and actions) are clearly helping to “drive” a new norm there.

Learning from indigenous norms

This brings me to a third set of comments from my Psychology Department colleagues that suggested learning from indigenous or native peoples. In particular, as one attendee expressed, we need especially to overcome a “property rights view of nature” inherent in Western law and philosophy. A good point indeed, and it does seem that there is an outsize impact of thinking of a tree or a forest as property, intrinsically similar to one’s house or car or boat, and a part of the collection of property objects that we enjoy and dispose of on a whim.

The inverse is to understand trees and forests as part of a collective stock of interdependent relationships necessary for the survival and flourishing of all; something to steward over for the good and enjoyment of the entire community. Changing the psychology of trees and forests so that they are closer in our minds (and in our legal systems) to wetlands, coastlines, oceans, sunlight, climate, etc. would give them a higher status and would definitely change the decisions we make. There are already legal principles and precedents, for instance, the Public Trust doctrine in common law that would help apply these important indigenous ideas. And changing even the way we talk about trees (with gendered pronouns, as Robin Wall Kimmerer suggests: a tree should never be described as an “it”), could help to cultivate a new status or position for trees.[8]

Native Americans view trees and forests through a lens of reciprocity and kinship. As Kimmerer says, trees are “standing people”, and deserve reverence and care, as would a member of one’s family. This may be a step too far for many, but if we begin to see trees as kin, we are, of course, less likely to destroy them for trivial reasons.

In addition to new short films about efforts in Atlanta (mentioned above), we have also recently made several short films about trees and tree-conservation efforts in Seattle. One of these seeks to tell the story of efforts to protect an ancient western red cedar and to raise general awareness of the number of trees threatened by developers and the fairly lax tree ordinance that fails to protect them. In the end, this magnificent tree was saved, partly through the nonviolent direct action of people occupying the tree. But giving this tree a name―Luma, in this case―was quite an important step. It is again hard to cut down a tree that has a name and name that many in the community accept and use. A name implies that this tree is a person, a someone, a sentient being, and in so doing once again changes the psychology at work.

The approach taken by the defenders of Luma is very close to the native American ideas about trees and nature. Luma is essentially kin, a living member of a reciprocal community of life, and as such a person meriting protection. The short film below tells this compelling story (see the link below). One of the early steps taken by tree advocates such as Sandy Shettler of Tree Action Seattle has been to track closely the permits issued for tree removal by the City of Seattle and to organize public “gratitude gatherings” the day before trees are slated for removal. These have been powerful and emotional events and have been covered by the local press. In August 2023, I had the privilege of attending one such event to celebrate and say goodbye to a pair of large and old Douglas fir trees, soon to be lost to a development in western Seattle. It was a moving evening and at the heart is the idea that these trees are (again) not simply inanimate objects to be casually killed but living persons with legal and political status.[9]

Photo credit: Tim Beatley

The legal rights of trees and forests is a matter of growing discussion but one clear way to change the psychology of trees would be to adopt a stringent tree protection code which some cities have been able to do. And the better codes have saved important trees. Such laws and codes, and even publicly debated and disseminated policies, are themselves ways to change psychology. Laws and ordinances send critical moral signals about many of the things already mentioned above―they first of all help to dispel or dissuade one of the ideas that cutting down that tree, at least a protected tree of a certain age or size―is entirely an individual decision. It is not and the law requires one to seek some level of permission to cut it down and only under certain special circumstances (e.g., it is dead or dying, creates a public hazard, and so on).

Part of what we need in cities is (and this verges on another norm) a mechanism that slows down the process of gaining legal permission to cut down trees. The example of Atlanta’s tree code shows how these signals might be conveyed. One especially interesting provision there is that neighbors have the right to appeal for a tree removal permit, and neighbors often do. In one recent case, a developer sought to cut down a large and beautiful southern red oak in order to build a large single-family home. Neighbors appealed the decision to Atlanta’s Tree Conservation Committee, which in short order re-designed the configuration of the house, including shifting the driveway from one side to the other, moving the home back on the lot slightly, and showing how it was indeed possible to build the house but also protect the tree.

Neighbors heard about the tree removal from mandated signs posted onsite and the appeal itself was posted once made. While not a perfect tree ordinance, and one currently being revised, there is at least a prevailing sense there that there is a legitimate public interest in protecting trees and that the public has a right to challenge an individual property owner’s plans or desires. Back again to the importance of neighbors and neighborhood action!

A systems view

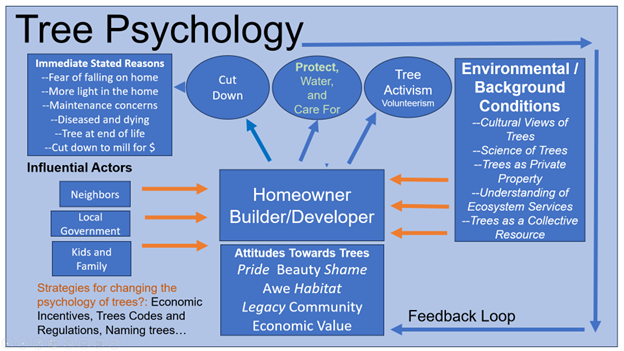

Thinking more holistically, there are likely numerous factors that affect the way we see trees and how we treat them, and many other things that influence the collective psychology of tree conservation. With this in mind, it has been helpful to me to pull out of the deep recesses of my graduate education in political science the groundbreaking work of David Easton. Easton is famous for proposing a “systems model of political life”, essentially a comprehensive “flow model” explaining political outcomes by the complex interactions of the environment (including ideology and public opinion), what he called demands and supports (triggering actions or proposals, and the positive and negative factors that might help a proposal or proposed action prevail politically).[10] There is also an important role of a feedback loop, understanding that outcomes, in turn, influence the next round of proposals. Easton’s model was not meant to predict or explain the outcome of a homeowner’s decision or choice, or explain the psychology involved here; it was aimed more at explaining a political outcome, a decision for example of a local city council.

While some of the language of this model is off-putting and can sound a bit too mechanistic at times, the essence of it seems to me to be valid. I have attempted to shape my own version of Easton’s model to help show where key influences might exist and where there are especially promising or important points of intervention. If we want decisions favorable to the protection of trees―which might be the adoption of a strong tree protection code, or a municipal budget allocation sufficient to care for trees and forests in our community―we need to muster the necessary political support and power. That might take the form of crafting and advocating a specific proposal or working on amassing the political support and a coalition of organizations that together can exert the political influence to gain its adoption. Or it might suggest the need to challenge (as I have earlier) the norms and values and the larger environment that shapes how we see and value trees and forests.

A key element of the systems model is the feedback loop, which helps to highlight the unintended consequences of some decision or action―for instance, low budget allocations for the care and watering of a city’s trees lead to high mortality, which may help to set the stage later for setting aside more resources to prevent this from happening in the future. The chance for a community to learn from a mistake or earlier decision that has been made about trees and forests is critical: making visible the “feedback loop” in a way that changes the politics (and the political outcome). There is the promise that feedback loops work at the homeowner or property owner level as well: cutting trees down leads to hotter homes and higher energy bills, and (hopefully) more appreciation of and care for the trees around them.

The diagram above is meant to suggest most importantly that there are many factors and influences that impinge on the choices we make about trees, individually and collectively, and also to help us begin to sort through some of the potential interventions that might change these outcomes.

The diagram above is meant to suggest most importantly that there are many factors and influences that impinge on the choices we make about trees, individually and collectively, and also to help us begin to sort through some of the potential interventions that might change these outcomes.

Could we change the outcomes by changing the politics around trees? For instance, bolstering the number and relative influence of groups in the community that support tree protection? As I have argued earlier, outcomes are shaped by the larger culture and environment and there is a need to both build onto existing norms but also to cultivate and strengthen new or emerging norms around trees.

Changing the economic and financial incentives faced by property owners and developers might help to change the outcomes as well, something I have advocated for years. Could we not imagine a new kind of taxation system that would give credit for trees and natural landscapes that deliver important collective ecological benefits, and impose lower taxes, while doing the reverse for ecologically damaging landscapes? There is considerable precedent for paying homeowners and property owners to protect trees and nature―if each large tree over a certain size gained for the owner even a few hundred dollars a year in income, it would be much harder to imagine that tree being cut down or removed.

What steps or interventions will have the most positive effect will vary from place to place, perhaps from circumstance to circumstance. But there will I believe be many necessary opportunities and pathways to shift the psychology of trees and forests in ways that they are in the long term cherished and protected.

Tim Beatley

Charlottesville

[1] Joan Maloof, Nature’s Temples: A Natural History of Old Growth Forests, Princeton University Press, 2023, p.56.

[2] https://vivent-biosignals.com/

[3] For some interesting new research about this see Juntilla et al “Tree Water Status Affects Tree Branch Position,” Forests 2022, 13(5), 728; https://doi.org/10.3390/f13050728.

[4] Sophie Legros and Beniamino Cislaghi, “Mapping the Social-Norms Literature: An Overview of Reviews,” Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2020, vol 15(1): 62-80.

[5] For more about city tree maps see Beatley, Canopy Cities, Routledge Press, 2023.

[6] This is an idea described more fully in Beatley, Native to Nowhere, Island Press, 2005.

[7] E.g. see Charlottesville Area Tree Stewards, https://charlottesvilleareatreestewards.org/; Almere Green Neighbors, https://klimaatadaptatienederland.nl/en/@248421/green-neighbours-encourage-other-almere-residents/; Dunbar/Spring Neighborhood Foresters, https://dunbarspringneighborhoodforesters.org/be-a-neighborhood-forester/neighborhood-forester-inspirations/

[8] See especially Kimmerer, “ Speaking of Nature: Finding language that affirms our kinship with the natural world,” Orion, 2017.

[9] See “VIDEO: ‘Gratitude gathering’ beneath two doomed Gatewood trees with advocates who say ‘housing vs. trees is a false dichotomy’, August 17, 2023, https://westseattleblog.com/2023/08/video-gratitude-gathering-beneath-two-doomed-gatewood-trees-with-advocates-who-say-housing-vs-trees-is-a-false-dichotomy/

[10] For lots more detail see David Easton, A Systems Analysis of Political Life, John Wiley and Sons, 1965.

Leave a Reply