If a tree can bring luck to the hand of the person touching it, can that hand bring something to the tree? It’s nice to think that we can have reciprocal relationships with nature.

In 2020, to halt the building of a logging road in Canada, a group of activists set up blockades to protect woodland in British Columbia. A Pacheedaht elder named Bill Jones was quoted in The Guardian as saying, “We must not stand down”. He went on to call ancient trees “guides, teachers, spiritual beings”.

I dragged a link to this article into an open document. It joined fragments on the connected roots of the words tree and duration, the translation of lo spelacchio (the mangy one), the name given to Rome’s official Christmas tree in 2017, pictures of women posing in front of palm trees at the 1939 World’s Fair in Queens, NY, and an exhortation to “look up tree funeral in Flushing!”.

Buy A Tree Grows in Queens here.

I had been gathering lists and links, archival images, and my own photographs (oh so many pictures of leafy shadows on walls) for a project about trees. It was Jones’ comparison of trees to teachers that helped shape what would become this book. A Tree Grows in Queens is a meditation on the many ways in which trees manifest into other forms—from myths and memorials to meeting points and harbingers of luck. Taking inspiration from trees found in old-growth forests and the streets of New York City, the book cultivates an intimate connection between the city’s ecology and heritage by examining individual trees and their interdependence with broader concerns, such as climate change, capitalism, and urban revitalization, alongside their significance in our everyday lives.

Magali Duzant, published by Conveyor Editions

- The Right Fit

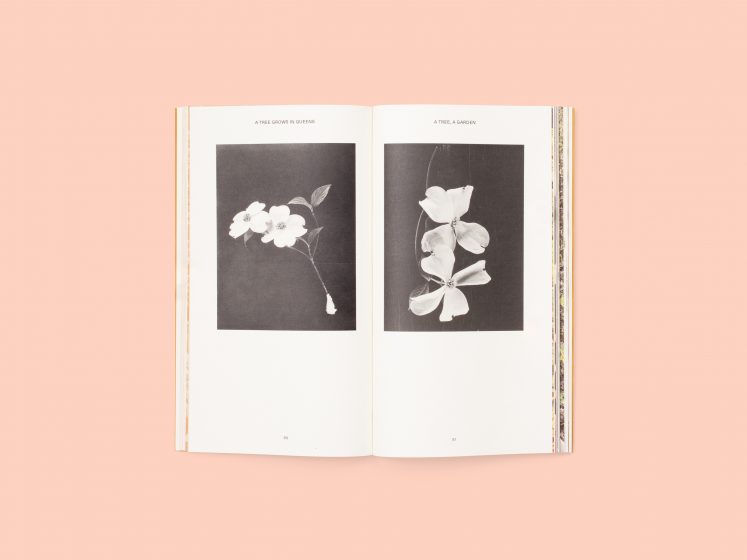

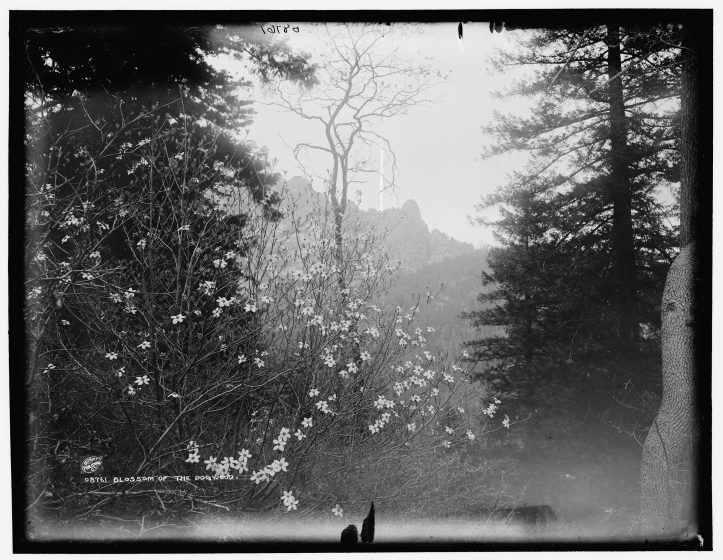

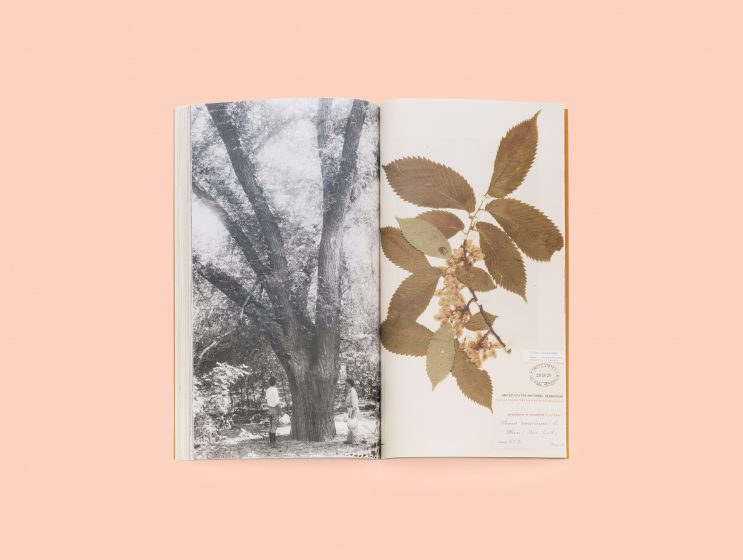

Flowering Dogwood, Cornus florida

When my mother was young, she and her sisters decided to surprise their mother with a gift for her garden. My grandmother Joan is well known for her obliviousness. She once wore her shoes on the wrong feet for an entire day, not realizing it until she returned from work, complaining that her feet were killing her after the walk from the subway. In my family, when someone does something silly, something without thinking, we say, in a bemused tone filled with love, “Oh Joooaaaannn”. This is how her daughters managed to sneak a small tree into their family station wagon on a trip to a nursery and get it home without her noticing. On Mother’s Day, they led her into the garden, where a small flowering dogwood had been planted in the night. The tree had pink cross-shaped flowers and was by all accounts a lovely addition to the yard.

Magali Duzant, published by Conveyor Editions

One morning, several years after the tree was planted, my mother went out into the yard and found the dogwood missing, simply uprooted and disappeared. My grandfather later admitted that he had dug up the tree and replanted it in Forest Park. The story is strange, and I can’t tell if it came out of a fight, some form of excessive revenge or marital malice. In his later years, my grandfather would sometimes say that he and my grandmother just weren’t the right fit. I imagine him silently digging up the tree, driving it to the park, and . . . replanting it? In my mind this must have taken place at night, much like the original planting; it forms a perfect loop of nocturnal gardening. There is something absurd in how this act of anger and hurt was tinged with just that extra bit of practicality, a result of a Depression-era childhood that profoundly shaped his ideas on thrift and waste and touched so much of what my grandfather did.

Between 1880 and 1899

No matter how hard I have tried to find the tree, hiking in and out of trails in Forest Park, I have never managed to find it. The dogwoods I find are always white. Deep down I know how improbable it is that fifty years later I could somehow find a particular tree I had never actually seen, planted somewhere within the forest. But it’s nice to imagine that one day I’ll turn and see it, a scattering of pink-tipped flowers amid the wash of greens. A tree with a second life, a tree that might have finally found its right fit.

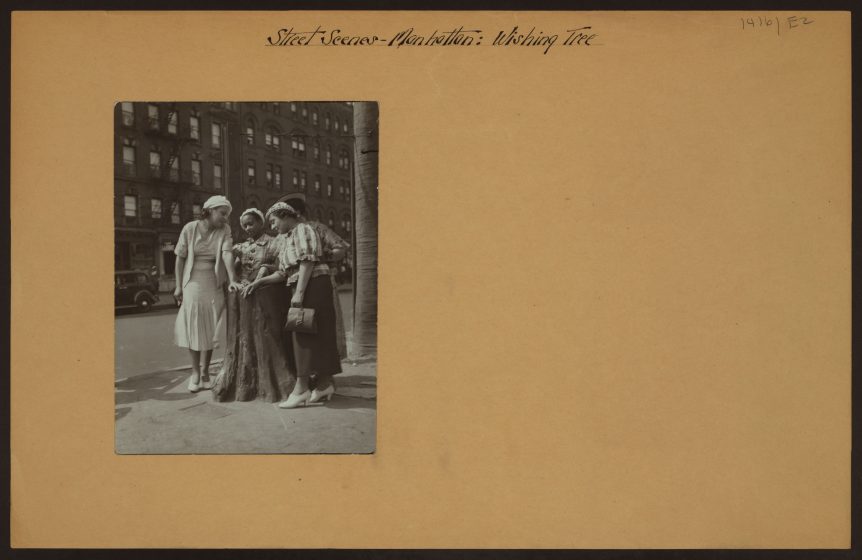

- The Harlem Wishing Tree

American Elm, Ulmus americana

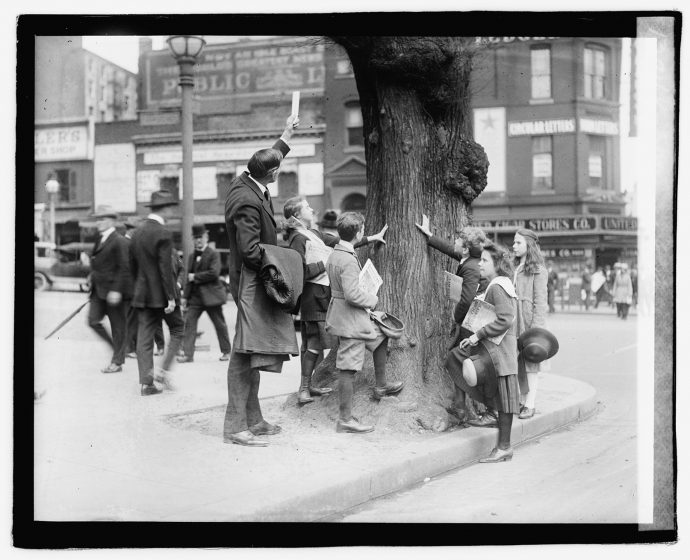

These days, the notion of seeking something out in public to rub or touch seems somewhat horrifying. When the COVID-19 pandemic engulfed the world, a form of ritualistic hygiene emerged. Prior to understanding the aerosol aspect of the virus, experts told us to wash our hands often, wear gloves, and avoid touching surfaces. This led people to hoard hand sanitizer and antiseptic wipes, wash every item they purchased at the bodega, and leave packages in the mail room for days before handling them. But before the pandemic, people purposefully sought out communal surfaces to rub, touch, or, in the unsurprising case of female statues, grope. Tourists worldwide kissed the Blarney Stone; rubbed the arm of Everard t’Serclaes in Brussels or the snout of Il Porcellino in Florence; and, because even statues of women can’t escape indignities, caressed the breasts of the Juliet statue in Verona or the Molly Malone statue in Dublin (alas she is also called “The Tart with the Cart”). In the 1930s in New York, if one was looking for luck, they might find some in Harlem at the Tree of Hope, also known as the Wishing Tree.

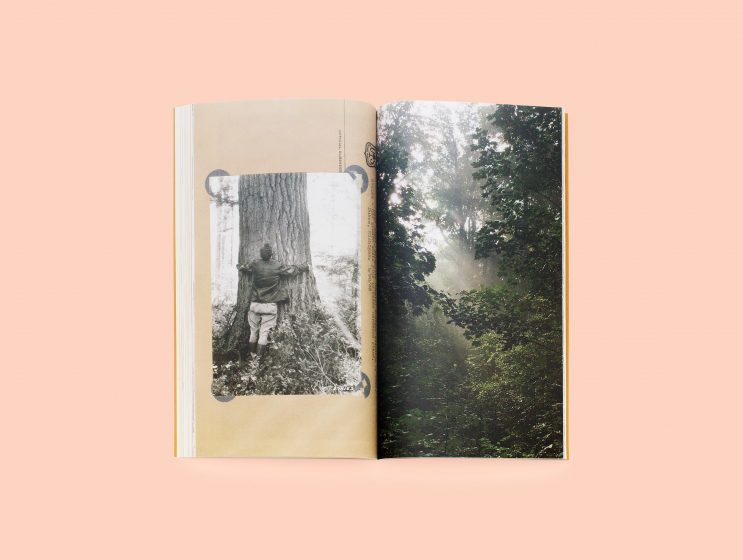

If a tree can bring luck to the hand of the person touching it, can that hand bring something to the tree? It’s nice to think that we can have reciprocal relationships with nature. In the 1970s, hands saved a forest of trees and gave birth to the modern concept of tree hugging. The Chipko movement or Chipko Andolan was a response to the rapid development experienced by the states of Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh. Chipko in Hindi means “to cling to or embrace”. In 1973, in the village of Mandal, villagers were denied access to a stand of trees; they were planning to use them to build tools but the stand had been sold to a corporation for logging. In an act of protest, the villagers embraced the trees to prevent them from being felled. The Indian environmentalist Sunderlal Bahuguna helped spread the movement’s tactics throughout the state and coined the slogan “Ecology is permanent economy”.

Magali Duzant, published by Conveyor Editions

In 1974, the Chipko movement emerged in the village of Reni, when the male inhabitants were invited to a nearby town, most likely to get them out of the area as the forest was cleared. This left the women of the village, led by Gaura Devi, to confront the loggers. The pictures taken that day show women hugging the trees, holding each other’s hands to wrap themselves around the trunks, as an unbreakable chain. The ripple effects of the protest actions swept across the Indian state, giving birth to a decentralized movement for forest rights. The villagers understood the reciprocal relationships at stake: yes, the forest was a resource, but one to be treated with care, not exploitation.

Magali Duzant, published by Conveyor Editions

In the years that followed the first Chipko action, tree hugging and tree sitting spread beyond India’s borders to the forests of New Zealand, Germany, and Northern California, and on to my university campus in Pittsburgh, where a beloved sculpture professor scaled a tree in the nude to protest the slated destruction of it and others for the building of a robotics center. The term tree hugger has become a most derogatory remark in wider Western culture—one that is often associated with a white-hippie caricature obscuring the actual history of the movement. In 1730, the very first recorded tree-hugging action was carried out by members of a Bishnoi Hindu village; roughly 350 inhabitants sacrificed themselves, murdered for protecting their Khejri trees. A royal decree of protection on all other Bishnoi land was introduced—the villagers had given their bodies for their trees.

***

Touch can be a form of activism. It can be a form of compassion, shared between two organisms, a moment of understanding something larger than oneself. Touch can spark many things, from worldwide movements to small moments of luck.

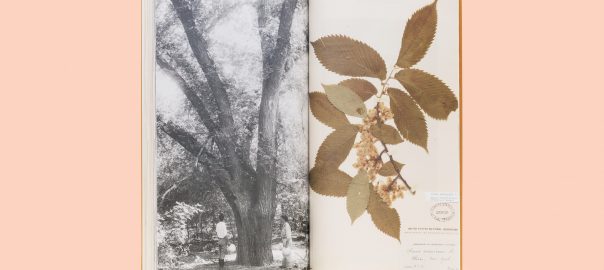

Photograph showing Clifford Lanham, District of Columbia superintendent of trees and parking, talking to kids from the Burroughs Club about the Morse Elm before it is cut down.

(Source: National Photo Company, Washington Times, May 14, 1921)

Magali Duzant, published by Conveyor Editions

Magali Duzant

New York City

Leave a Reply