Introduction

about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

Whimsy: Playful or fanciful ideas that bring a sense of fun and imagination.

Whimsical: Full of playful charm and imagination, often with a touch of unexpected delight.

Release your balloons and wonder at them as they float around a roomful of ideas.

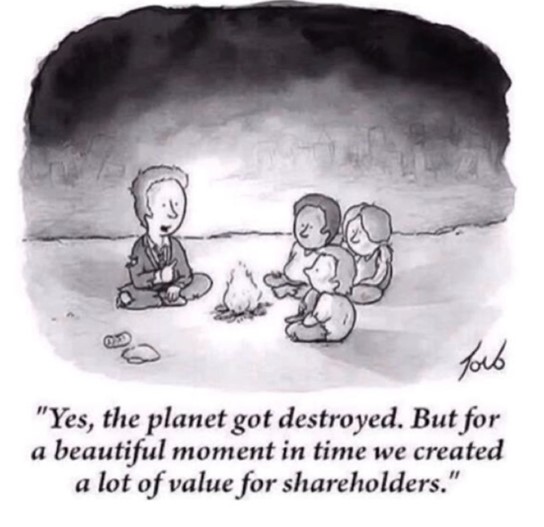

Sometimes, we see something that makes us laugh out loud because it surprises us with an unexpected new perspective, or a funny joke that makes us understand something in a new way. Or an element of joy or romance. Or maybe a bit of melancholy. Or a bit of wry non-sequitor. One-frame cartoons are often whimsical. Weird cool. Clown performers do it all the time. (OK, unless you think clowns are scary.)

Whimsy can be slyly subversive of dominant narratives.

Whimsy. Rooted in words that mean: to let the mind wander, a sudden turn of fancy, to flutter, a whimsical device, a trifle.

The science involved in biodiversity conservation, climate change, nature-based solutions, and sustainability can be heavy stuff, sobering, even upsetting. Dare I say sometimes boring? Maybe a whimsical note in some form can play a role in spreading knowledge and ideas. Maybe it can attract people to movements toward sustainability? Can it bring new people into the conversations? Can it help us see more clearly? Or see for the first time some essential thing?

Maybe it can just lighten our spirits a bit so we can dive back into the serious business of saving the world. That would be useful just by itself.

I think it is that and more, too. I think whimsy can help us learn.

So, we asked a diverse collection, from scientists to performers, artist to practitioners. Plus one professional clown.

Joy.

“Whimsy” is a playful, creative approach to seeing the world, marked by lightness, curiosity, and a sense of wonder. It invites us to break from rigid thinking and explore new possibilities, offering surprising, delightful perspectives that reveal unexpected insights. Whimsy helps us to question assumptions and view situations with fresh, imaginative eyes, opening pathways to new ideas and fostering innovation. Far from being trivial, whimsy is a powerful tool for expanding understanding, as it encourages us to approach challenges with openness, creativity, and a touch of joy.

NOTE: “Whimsical” can sometimes be defined in vaguely pejorative ways, like a grouchy curmudgeon might do: “capricious”, or “ridiculous”, or “a distraction from serious work”. The whimsy we are looking for here is something else. It may be funny, or weird, or sad, or laugh-inducing, or inspired, but it isn’t capricious in the “stupid and useless” sense.

Can you imagine adding a one-frame cartoon as an ironic joke to every policy brief? I can.

The word “whimsy” or “whimsical” doesn’t translate so well outside of English. Translating “whimsy” into other languages can be challenging because it captures a delicate blend of lightheartedness, imagination, and playful charm, which doesn’t always have a direct equivalent. In English, “whimsy” evokes a positive sense of spontaneity and innocent creativity—qualities often culturally specific or expressed differently in other languages. Some languages may have words that convey aspects of whimsy, such as “fantasy” or “playfulness”, but these can lack the same light, imaginative nuance or might even carry negative connotations.

Whimsy is both light and profound, imaginative yet innocent.

Romance languages such as French or Spanish have words for playful or fanciful ideas (e.g., “fantaisie” in French or “capricho” in Spanish), but these perhaps miss the purely innocent charm of “whimsy”, sometimes implying unpredictability or indulgence rather than lighthearted creativity. In German, “whimsy” might be expressed as “Laune” or “Einfall,” which relate more to mood or a passing notion and lack the childlike creativity that whimsy implies in English. In some Asian languages, where expressions can lean toward structured formalities or poetic metaphor, capturing “whimsy” may involve combining concepts, like creativity and playfulness, to communicate the intended nuance, perhaps through descriptive phrases rather than single words.

Ultimately, the challenge lies in the unique cultural and linguistic framework that “whimsy” embodies in English—a trait that’s both light and profound, imaginative yet innocent—which doesn’t always have a ready counterpart in other languages. It is the same difficulty that can arise in communication between disciplines speaking in the same language.

In whatever language, release your balloons and wonder at them as they float around a roomful of ideas.

Alastair McIntosh

about the writer

Alastair McIntosh

Since 1996, his work has been mainly freelance as a human ecologist, writer, speaker, researcher and activist. Alastair is a Quaker, an honorary senior research fellow (honorary professor) in the College of Social Sciences at the University of Glasgow, and as a Fellow of the Centre for Human Ecology was Scotland’s first professor of human ecology at the University of Strathclyde. He has also held honorary fellowships at the Academy of Irish Cultural Heritages (University of Ulster), the School of Divinity (University of Edinburgh) and the Schumacher Society.

Through the eye of a potato: Tips on writing a thesis in Human Ecology

Enjoy your thesis, and open others up to visionary possibilities.

I would like to share a few words about what, in my experience, is important in writing a scholarly thesis in the relationships between the social and the natural environment, and having fun in so doing.

Let me assume that you are here to do a master’s degree, and your thesis, in the old model of apprenticeship learning, is your “masterpiece”. It is that with which you can show the world that you are a competent human ecologist. For this reason, choose something that is useful―something that you can do things with―like publishing it for others’ edification, or to influence people or a movement, or to bear witness. Your work may well serve personal intellectual or even therapeutic interests, but if it is constrained to that, it will be a narcissistic piece, which is not why we are all here. So, please, my suggestion would be to set yourselves a fundamental framework of operation by asking yourselves, “Is it going to be of service to either the poor or the broken in nature?”. If the answer happens to be “no”, that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re off the track, but I would urge careful discernment―careful sifting of your motives―so as to reveal more clearly who or what it is that you serve.

As your masterpiece, try and integrate the fullness of human ecology into the wider framework. Ensure it has linkages to the social and the natural environments. Strive to convey the passion of the heart, guided by the reason of the head, applied with the practicality and sheer hard work of the hand.

But, and it is a huge “but”, in holding everything in a framework that is nothing less than your worldview―your cosmic experience of being alive on this planet―develop a sharp focus. If you don’t, you’ll be all over the place. You’ll get into a horrible flap, and be a considerable pain in the flapping parts of the anatomy to your poor supervisor.

Remember, a stone mason doesn’t start with the whole mountain, or with the cathedral that she is to build. She chooses a small part from the mountain, and contributes to the pattern of a whole that is greater than she herself.

How do we do this? My suggestion is to think of your thesis in terms of story. Ask yourself, “What is the beginning, middle and end?” Find a small question, a very small question, and ask it. But ask it well. As a 1965 Ned Miller hit put it, “Do what you do well”.

For example, don’t focus on saying, “I want to examine nutrition in Scotland, or England”. Run with a small question like, “I want to study who is buying organic potatoes in Edinburgh, or Liverpool”. Then you’ve got something that you can research and handle easily. Then you can go round all the shops―I guess maybe only 20 or so―and interview the shopkeepers or the customers. In a containable manner you can analyse your data, set it in the context of the relevant literature, and end up with a concluding chapter that reflects on the relevance of your well-grounded findings for your wider interest in nutrition.

Do you see from this small example how helpful it is to think in terms of telling a story? Your story would go like this: I was interested in this big picture, and I spent a couple of weeks thinking and reading around it. I then refined it down to one (or at most, two or three) questions. Over another couple of weeks, while still doing my literature review, I developed a robust methodology for how I was going to explore those questions. I tested my methodology on a few friends, tweaked it a little, until I was satisfied with the result. I then spent a couple of weeks carrying out the interviewing (if that be your approach), and then allowed four weeks for analysing what I’d done and writing draft chapters. This left me two weeks at the end to write up a polished version … which I was able to proudly deliver to my supervisor (with a large bottle of organic malt whisky).

There you are. Total job finished in 12 weeks, which is roughly what you need to be looking at in a typical master’s thesis if you’re going to manage your lives, and work well, and allow a little slack time for possible technical problems, sickness, a broken heart, a mind-blowing mystical experience, or … too much whisky.

And notice how, in all of this, you have never deviated from following the silver “faerie path” of your passion. The discipline you will have had to apply in following that passion will have been your “working under concern”, your calling, your vocation at least for the time being. It will leave you with a great story to tell, a very practical one because it is grounded, and something that may be, above all, a contribution to the cause, to “the great work”. Neither will your wider interests have been frustrated by choosing such a specific focus. Indeed, if your focus fell upon the vegetable realm, my bet is that you’ll end up finding that you can see the whole world through the eye of a potato.

You can see how such a thesis could easily be published. For example, a scholarly paper in a journal of agriculture or retailing, or an article in a permaculture newsletter, or in a greengrocer’s trade magazine. If you need to dress up such an honest-to-goodness approach to serve what Mary Daly called “academentia”, you can justify it in through such qualitative social research methodology as “grounded theory”.

One last thought … my late friend Ralph Metzner of Leary-Metzner-Alpert fame at Harvard in the 60’s, “stardust” and “golden”, had a wonderful saying. “Stories are what tell us of the past: visions tell us about the future”. Enjoy your thesis, and open others up to visionary possibilities.

As added whimsy, is an excerpt from the closing part to Alastair’s Sermon

“Lesson to The English on And Reform at Dark Mountain in Wales. The Sermon Application”

Sermon Application – Lifelines

A likely Gaelic derivation of Tom Forsyth’s name is Fearsithe, “the Man of the Faeries” or “Man of Peace”. But getting him to Llangollen (The meeting place for the event) had been anything but irenic. It had been a complex two-day journey by small boat, bus, and trains. Being in his eightieth year, and with reduced agility, we struggled with the tightly-timed connections between stations. Finally, the two of us were seated on Dark Mountain’s stage.

I spoke. Tom held silent presence. I invited his contribution. But he just sat.

After what seemed an age, he reached into his shirt pocket and held up on a chain an antiquated watch.

“I see that here you live by deadlines”, he said, referring to the journey.

“Where I come from, we live by lifelines”.

And then, he just sat there: slowly shaking his head, as if beguiled in wonderment.

At length, he added a little more. The butterfly may look as if it’s wander-ing aimlessly through the garden. But don’t be misled by the butterfly mind. It’s following its nectar to the source. That was Tom’s message, to Time to Stop Pretending.

I thought: “Is that it?”

Then, of course: that’s it!

And I raised my eyes to the balcony that ran around our seated auditorium. In full Highland Dress, appeared MacKinnon of MacCrimmon. (Ian is one of the most acclaimed Highland bagpipers of the Scottish Highlands and Islands tradition).

And I rooted my feet to the ground. And I shouted at the top of my voice.

IAN, WHAT IS SPIRITUALITY?

And the pipes skirled. And then he burst into an ancient Gaelic song.

And the assembled bards … and the Old Things on Dark Mountain …… stirred at the Gates of Dawn.

Full Sermon Available:

https://www.alastairmcintosh.com/articles/2024-Dark-Mountain-Sermon.pdf

David Maddox

about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

It is graffiti in an unexpected place, and with an unexpectedly peaceful subject. It causes us to pause for a moment and linger too, and think about that imaginary woman. And also think about what the creator of this picture was thinking.

Much of what we encounter as creative graffiti is whimsical. I am not talking about tagging here, but rather the story oriented graffiti exemplified by artists such as Banksy. Think, for example, a masked protester hurling … flowers (Bansy’s Love is in the Air). Love is in the Air juxtaposes rebellion and tenderness. It challenges perceptions by melding a violent act with a peaceful gesture, urging us to imagine alternatives. The unexpected image of a protester throwing flowers provokes thought about love, resistance, and societal change, inspiring us to reconsider our approach to power, protest, and hope.

TNOC started The Nature of Graffiti a few years ago to explore such juxtapositions in the context of nature. It is a gallery of nature-themed graffiti around the world, and there is a lot of it. Cape Town, Bogotá, and Calí are full of it. Other cities, too. Painted birds on walls. Chimeras of zebras with human heads. Scenes of people gathering food. Messages of environmental and social protest (“Belo Monte de mentiras“, referencing an Amazon watershed dam that has disrupted nature and communities). Funny juxtapositions.

One image has always lingered for me. It was up one of the steep hillsides in Bogotá, in a poor neighborhood. Almost all of the water used in Bogotá flows down from the hills next to the cities, in rivers and streams that pass through these neighborhoods. It is graffiti of a woman sitting next to an actual river and its flow. She is enjoying it. Contemplating it. Appreciating it. Lingering with it.

And it is graffiti in an unexpected place, and with an unexpectedly peaceful subject. It causes us to pause for a moment and linger too, and think about that imaginary woman. And also think about what the creator of this picture was thinking.

Lisa Fitzsimons

about the writer

Lisa Fitzsimons

Lisa holds a MSc in Climate Change: Policy Media and Society from Dublin City University (DCU) and serves as the Strategy and Sustainability lead at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) in Dublin.

The power of moments of levity

Rather than overwhelming audiences with technical jargon and complex concepts, light-hearted communication invites them into the conversation and perhaps makes them start to think differently.

Effective communication is critical to driving social change to motivate people to take action, change their habits, and push for policy changes, and how we frame climate change shapes how audiences understand and respond to it. Usually, the climate crisis is framed in terms of science, politics, economics, or ethics. While facts and data are important, data and scientific information alone will not inspire change. Indeed, audiences’ lack of emotional connection to climate messaging can explain why they aren’t taking action.

A cultural framing of the climate crisis, however, has a stronger potential to resonate meaningfully with audiences. Our understanding of the climate crisis and how we respond to it is shaped by our culture―our beliefs, values, traditions, and ways of thinking. Comedy and moments of levity in culture can help make the heavy topic of the climate crisis more approachable and relatable and can help diffuse tension, offering a potentially powerful tool for shifting communications and attitudes.

Comedy has always been an important part of cultural expression, from Ancient Greece and Shakespeare to memes and internet humour. Comedy’s power lies in its ability to hold a mirror up to contemporary society, to create a feeling, move us emotionally, or change our perception. Done well, it can communicate complex issues, such as race, inequality, and the climate crisis, in relevant and meaningful ways.

Indeed, throughout history, comedy has played a central role in social movements, serving as a tool for communications and mobilisation. African American comedian Dick Gregory used humour to highlight racial injustice in the 1960’s. Hannah Gadsby’s Netflix stand-up show Nanette blends humour with raw honesty about the struggles of being queer. And through shows like Saturday Night Live and 30 Rock, comedians Tina Fey and Amy Poehler successfully use humour to challenge gender stereotypes and to advocate for women’s rights. In all these examples, comedy serves as a tool for social mobilisation by making complex, often controversial issues more accessible, challenging power structures, and uniting audiences through laughter.

When we use comedy and moments of levity, we create a shared space where people can acknowledge the seriousness of the problem without being overwhelmed by it. Contemporary comedians are increasingly using humour to tackle climate change topics and, in doing so, help bring the issue into everyday conversations in a more engaging way. The Irish comedy group Foil Arms and Hog, for instance use insightful humour to great effect to communicate the ridiculousness of inaction in the face of the Earth Crisis. This kind of humour lowers the audience’s defences, allowing them to engage with the issue without feeling judged or isolated. Rather than overwhelming audiences with technical jargon and complex concepts, light-hearted communication invites them into the conversation and perhaps makes them start to think differently.

Laughter can break emotional barriers, making room for learning and, ultimately, action. When people laugh together, they feel connected. Shared laughter creates a sense of camaraderie, which can make people more willing to listen to different perspectives. And when people feel like they’re part of a community, they may be more open to considering new ideas or changing their views. Humour can tap into emotions such as joy, relief or even curiosity, shifting how people feel about an issue. These positive emotions can encourage people to be more optimistic and proactive rather than paralysed by fear or guilt. Irish collective We Built This City on Rock and Coal brings scientists and theatre makers to rural and coastal towns across Ireland for an interactive performance driven by research and comedy. It’s good fun and good for the planet, helping individuals and their community become part of a collective action.

That said, however, while levity is powerful, there is a fine line between engaging people with humour and making light of a dire situation. The key is balance. Levity should complement, not replace, the serious messages at the core of climate communication. Blending moments of lightness with critical information to ensure the humour supports the call to action without diminishing the issue’s urgency.

Ian Douglas

about the writer

Ian Douglas

Ian is Emeritus Professor at the University of Manchester. His works take an integrated of urban ecology and environment. He is lead editor of the “Routledge Handbook of Urban Ecology” and has produced a textbook, “Urban Ecology: an Introduction”, with Philip James.

I suddenly saw a mass of young trees and shrubs that had invaded the vacant space: a piece of wilderness in the commercial heart of the country.

My moment occurred in 1954 when I was 18 and was in a group taken to visit the City of London by our History sixth former teacher. Our school was run by one of the City’s ancient Livery Companies and its Hall had been severely damaged by fire in the 1940 World War II blitz. Even nine years after the war ended, the Hall had not yet been rebuilt. As in many British cities in the mid-1950s, derelict bomb-damaged sites were still common around London’s central business district. Walking from Threadneedle Street to the rear of the Hall, I suddenly saw a mass of young trees and shrubs that had invaded the vacant space: a piece of wilderness in the commercial heart of the country.

As a boy brought up in the 1930s suburbia of NW London, there were few spaces with wild nature. During the war, the park opposite my primary school was converted into allotment gardens for people to grow their own food. The golf course on the other side of the railway tracks was given over to the growing wheat, but some of the bunkers remained as tiny islands of wild nature, with trees and brambles, that an eight-year-old and his pals could explore by trespassing through the wheat. However, that land had always been covered by vegetation of some kind. The wild nature on the concrete and broken bricks of the City bomb site was something far more impressive: nature as reconquest, fighting back across the sealing of the land surface and the removal or burial of all previous traces of nature, to bring biodiversity back into neglected spaces.

The image of the urban wild near Threadneedle Street has remained vivid in my mind. In 1959, I acquired a copy of R.S.R. Fitter’s London’s Natural History (1945) which has a chapter on the influence of the war on London’s plant and bird life. This confirmed the importance of bomb damage in creating opportunities for invasive species and for drastic changes in avian activity. It was the first book I read about urban ecology. In Berlin at that time, Herbert Sukopp was studying the ecology of derelict sites and formulating a pioneering innovative, framework for urban ecology (Sukopp, 1959, 2003). David Goode (2014) describes how the London Natural History Society used 16 permanent quadrats and transects to record changes in the vegetation on bombsites in Cripplegate, just north of St. Paul’s Cathedral in the heart of the City. Rosebay willowherb and Oxford ragwort colonised early and then persisted, by 1955, 342 species of flowering plants and ferns had been recorded at these sites. My 1954 moment was a realisation that we really can find nature on our doorsteps and throughout the cities where most of us live, but the problem is finding ways to retain the urban wild and to open access to it for everyone.

Resources

Fitter, R.S.R. (1945) London’s Natural History, London, Collins New Naturalist No.3.

Goode, D.A. (2014) Nature in Towns and Cities, London, Collins New Naturalist No.127.

Sukopp, H. (1959/60) Vergleichende Untersuchungen der Vegetation Berliner Moore unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der anthropogenen Veränderungen, Botanische Jahrbücher, 79, 36–191.

Sukopp, H. (2003) Flora and vegetation reflecting the urban history of Berlin, Die Erde, 134, 295-316.

Pippin Anderson

about the writer

Pippin Anderson

Pippin Anderson, a lecturer at the University of Cape Town, is an African urban ecologist who enjoys the untidiness of cities where society and nature must thrive together. FULL BIO

(and also in conversation with Elsabe Milandri)

Lighter points of entry, playfulness, an element of surprise, are all useful mechanisms to draw people in to ideas that can feel overwhelming or too distressing to engage. The desire to look away from the climate catastrophe is strong and lighter approaches can make people turn their heads.

I’m a big fan of whimsy. The ethereal, the personally dictated, the hard to pin down, the amusing and nonsensical, the unexpected, and sometimes obscure and inexplicable. In fact, if they said they were going to cancel whimsy, remove it from society, and erase it from our dictionaries, I would definitely march to see it reinstated (I see it now, a small flock of people in hats with flowers and banners made of chiffon or holograms or some such, marching towards parliament chanting “Bring back whimsy, maybe”). There is an element of personal freedom in whimsy. And assuredly an element of joy. Whimsy must culminate in a smile.

But then my friend said maybe whimsy requires privilege. You can’t be whimsical if you are hungry or fighting for your freedom. And there are certainly a few places where whimsy does not emerge as useful. Gender-based violence, the Gaza genocide, micro-plastics to name a few. Perhaps climate change and biodiversity loss are on that list too. I also suspect whimsy may be something of a social sorting mechanism. A means through which we find like-minded souls or people who share our values and sentiments. Something of a secret handshake.

I might be wrong though. Years ago, artist Elsabe Milandri (@elsabemilandri) did a lovely piece―line drawing in ink on paper of a polar bear, and below it, she wrote (something along the lines of) “Remember that day we saw the last polar bear? I dropped my ice cream and cried and cried”. To my view she seems to use whimsy here (what is more whimsical that ice cream and a trip to the zoo?) as a counter foil to the terrible weight of biodiversity loss. She is of course using it to startle her audience in bringing together the mundane and the everyday with the shockingly absoluteness of the loss of species. I remembered this piece so clearly. I saw it years ago, hanging in another friend’s slightly edgy apartment in its black frame on exposed brick walls. I recall standing around drinking wine, small kids milling about us as we chatted and laughed. And all the time feeling the draw of that work on the wall.

My recollection of that piece of work inspired me to call Elsabe. As an artist and social activist, I wanted to get her views on the use of whimsy in garnering support for environmental causes I know are close to her heart. She felt very strongly that whimsy, or humour, is an excellent strategy to make connections. She said she feels those lighter points of entry, playfulness, an element of surprise, are all useful mechanisms to draw people in. In this way, she feels the more timid, or easily triggered, can come closer to ideas that can feel overwhelming or too distressing to engage. She feels the desire to look away from the climate catastrophe is strong and that lighter approaches make people turn their heads.

I think all these aspects might be true. As with all our current global crises, the role of privilege is highlighted again and again. We must certainly be mindful in all our engagements of our own positions and privileges. And it is possible that whimsy does sort us, into bands of like-minded garden gnomes or pods of mermaids. But I think Elsabe is right, there is certainly a role for playfulness and lighter approaches in drawing in the timid and re-igniting the interest of those who have given up hope.

Gareth Kennedy

about the writer

Gareth Kennedy

Gareth Kennedy is an artist and lecturer at the National College of Art and Design in Dublin Ireland. Since 2020, he has been lead coordinator on NCAD FIELD. Ongoing course work continues to explore the FIELD as a Novel Ecology and how it might support the creation of new Naturecultures and transdisciplinary exchanges.

If I can’t Dance I don’t want to be a part of your (r)evolution.

To work together through compelling experience and knowledge to see how we might shed our neoliberal skins and entertain other subjectivities and ways of being in the world together.

The students line the counter of Vincenzo’s Takeaway and Restaurant on Thomas Street in Dublin’s Liberties. Student anticipation mixes with their lecturer’s slight trepidation with how all this will unfold. Today the students are joined in their studies by members of Fatima Groups United, an active Age group who have joined today’s session to meitheal[1] with the students to harvest this year’s crop. FGU’s presence affirms a key tenet of the day’s learning: that sustainability is an intergenerational exercise that must collaborate with those who came before, and those who come after. The potatoes in question are particular. They are genetically diverse non-EU registered potatoes from Swedish artist Asa Sonjasdotter’s 10-year project[2] where she has collected potato varieties and their endangered biographies. Most of these potatoes do not meet the standard for EU industrial agricultural scale production in terms of productivity and also aesthetics. Some simply do not meet the aesthetic of what a supermarket-bought, pan-continentally traded archetypical potato should be. They are weird. One, The Rote Emma (Red Emma), is a copyleft renegade being deliberately left unregistered so as to activate other modes and scales of exchange wherever it is grown and its story told. It is named after Emma Goldman, the proto-anarchist/feminist of the late 19th/early 20th century. Students are always inspired by how the authorities of her day described her as an “exceedingly dangerous woman”, and of her motto for instilling joy and abundance in her activism: If I can’t Dance I don’t want to be a part of your revolution.

The chips, handcut, multicoloured, and like no others, are boxed fresh from the fryer and are brought back to the site of their harvest and our unusual place of learning, the NCAD FIELD[3] which is just next door. They are consumed communally and with relish plein air. This gives occasion to unpack the morning’s lectures and seminar. To appraise the potato as a medium par excellence to discuss issues surrounding colonisation, monoculture vs diversity, food security today, and how a famine 175 years ago still resonates in an Irish context. Most of all we are smiling and enjoying a collective glee in gleaning this carbohydrate-rich meal from our immediate environment. A student takes the excess in a box and wanders onto campus to distribute free chips as a surplus of the day’s study. Unchipped potatoes are carefully set aside as seed to be sown the following Spring to continue the cycle as a nascent tradition now in its 4th year.

Week by week students move through coursework intimately tied to the seasons. Critical texts, screenings and discussion are paired with material, haptic and often gastronomic processes. Students are asked to bring their stomachs and taste buds to class as we try to reconfigure our senses and entertain the idea of a novel terroir in in the FIELD. At time of writing (October 2024), as we leave the bounties and abundances of Autumn behind, we have made a course larder we will continue to dip into as we go into the dark winter months: Jam made from what maybe Dublin’s oldest pear tree[4] situated near the campus will be judiciously enjoyed as we reckon with troubling course material; the excess litres of delicious apple juice poached from unpicked orchards including a Protestant Bishops and a Catholic Convent ferment into cider which we will use to Wassail the end of coursework in January; after the first frost we will integrate the FIELD’s feral Kale into our coursework. This Kale, introduced in the time of the hipster, is now in its 7th generation of self-seeding on the site.

We mark Samhain (Oct 31st), the ancestral beginning of Winter and of the Celtic new year in our bioclimate, with a Halloween Special. We will visit the rewilded estate of film maker and Lord Dunsany, Randall Plunkett, who originally let his estate rewild to shoot his zombie apocalypse film[5]. A tour of the grounds will be followed by some witchery when we cauldron-cook elderberry tonic into a winter tonic to aid our immunity. The making of this bloodred tonic will frame the discussion of Silvia Federici’s Caliban of the Witch and how 400 years of witch hunts in Europe are tied to the enclosure and privatisation of land, the eradication of a whole world of female practices, collective relations, systems of land-based knowledge and also the birth of aggressive capitalist markets. This exchange lays a basis for discussing how reinstituting commons might help us rally and work together to create resilient systems in the face of what is unfolding. Afterwards, students will return to the city on Dublin bus with crimson-stained hands and smelling of campfire. All of this is serious fun and in the spirit of being generative and not extractive. To work together through compelling experience and knowledge to see how we might shed our neoliberal skins and entertain other subjectivities and ways of being in the world together. Joy, fun, craic, and whimsy are very much part of this unlearning.

[1] Meitheal – from the Irish language which traditionally means collective work undertaken to bring in a crop or perform other labour-intensive agricultural work.

[2] See www.potatoperspective.org/

[3] NCAD FIELD is a remediated and ‘guerrilla composted’ former carpark directly adjacent to the NCAD nested in the historic Liberties of inner-city Dublin. It was until recently a thriving site of urban horticulture before falling into disuse. The absence of human use, accelerated by the lockdown, led to a remarkable ‘wilding’ of the site. The eclectic biodiversity of the site today sees its reappraisal not as ‘brown field’, which speaks to a language of development, but as a Novel Ecology.

[4] See www.irishtimes.com/ireland/dublin/2023/09/27/liberties-pear-tree-more-than-170-years-old-dna-tests-show/

[5] See www.rewildingeurope.com/rew-project/dunsany-nature-reserve/

Tony Kendle

about the writer

Tony Kendle

After an apprenticeship in a small Parks Department, Tony studied Horticulture at the university of Bath. A PhD on land restoration at the University of Liverpool was followed by researching and teaching landscape management at the University of Reading where he developed a specialism in urban nature, publishing one textbook and one popular science book. Today he works with the Sensory Trust in Cornwall on helping communities take climate action with plants.

Humour and whimsy may initially be seen as inappropriate responses, but they may give us the strength to act, and they may also inspire our thinking to be more creative.

Humour and whimsey as tools to promote environmental care

Research has shown that humour can stimulate the release of neurotransmitters like dopamine and as a result it can enhance learning, memory, and creativity.

It is also widely recognised that humour can soften the stress and anxiety of dealing with difficult and terrifying topics including climate change.

I was intrigued then to find a researcher arguing for wider use of ‘eco-humour’ to address or even redress environmental harm in a journal article: Humour beyond human: eco-humour as a pedagogical toolkit for environmental education | Australian Journal of Environmental Education | Cambridge Core

People often laugh when exposed to an unexpected idea or one that changes their understanding. Somehow this seems connected to why surprising events and incongruous experiences strike us as funny.

A favourite quote of mine comes from Rob Hopkins who wrote that “tackling climate change is a challenge of the imagination” as in the face of a transformative crisis we have to re-imagine everything.

Bill McKibben has also written that we no longer live on the same earth as we used to climate change needs us to rethink everything.

So, amidst what UNEP calls the “polycrisis”―climate, biodiversity loss, health, and water―we seem to be firmly in the territory of the incongruous and unexpected; humour and whimsy may initially be seen as inappropriate responses, but they may give us the strength to act, and they may also inspire our thinking to be more creative.

The next issue is where should this humour be found and who gets to tell the story and the jokes?

The original root of the word museum was the home of the muses―places that curated creativity, inspiration joy more than information about random looted objects.

When I was first working on the establishment of the Eden Project, I tried (and failed) to inject whimsey into public interpretation. My thinking was that we needed to show that a concern for sustainability could be playful and that a greener life need not mean seeing all joy sucked away.

I quickly learnt that interpretation is a contested territory many people feel they have the right to own the narrative―interpreted knowledge rapidly becomes highly political if not actually weaponised, and it soon became clear there is no tolerance for whimsy in such contested spaces.

How then do we break the authoritarian hold on ideas in the public realm?

Recently I have become enthused by the work of the Rebel Botanists (#RebelBotanists – We’re shadows chalking on the street, to name the wild plants at your feet!)

Inspired by Toulouse botanist Boriss Presseq, they are on a mission to raise people’s awareness of the importance of wild to our ecosystem. They write “we use a street art approach to name the flora we find. The outcome is not confrontation, but curiosity―curiosity is the first step towards learning for all ages. The pavements become an evolving canvas, just as the seasons change so do our chalkings”.

In a grass roots unauthorised fashion, the rebel botanists form part of the movement for informal Science Learning that takes education out of the classroom.

I also see parallels with the movement to liberate museum labels from authoritarian control of the narratives. https://www.michellehartney.com/correct-art-history

Maybe the iron grip of narrative control is beginning to loosen under the strain of today’s challenges?

Potentially, the polycrisis will force us to rethink the entire paradigm of “sustainability”.

As Glenn Albrecht has challenged―just what aspects of our current environmentally dysfunctional culture are to be sustained?

It may be time, in the spirit of Coyote the Trickster, to harness our humour and disruptive imagination and use them to dismantle the domains of traditional science and education and to scatter the pieces through the streets like confetti―they can be reassembled one day as the new world germinates.

Gareth Moore-Jones

about the writer

Gareth Moore-Jones

Gareth has been involved in the sector for 30 years and has been CEO of NZ Recreation Association, National Sport & Recreation Manager for NZ YMCA, interim CEO of Outdoors NZ, and as public health planner in the health sector .

Bring on the whimsy! (but, as my daughters tell me, stop before you get the dad-jokes 🙂 ).

Imagine trying to explain the complexity of the message(s) contained in the Tom Torro carton below, using the English language (or other), full sentences, describing the context, the history, the present and the future and the science.

Imagine putting forward in your argument against fossil fuel use (or nuclear bombs…) in a way that encapsulates the messages of naivety, cynicism, capitalism, cult-theory, power imbalances, and a fully dystopian future, using academic references, footnotes, conventions that are all unspoken but present in the cartoon.

Your audience would be asleep before they figure out what your message is, let alone take it on board.

The power of whimsy or humour is that your audience almost instantly ‘get your message’ and, importantly, will most likely pass this on/forward on a social media platform. They don’t need to demonstrate an academic or scientific or even philosophical understanding of the issue―it is there, in a drawing and a few words. Whimsy is the best sharp object I’ve come across at popping the conspiracy-theory balloon.

Some of my colleagues suggest that whimsy reduces the seriousness of the topic and the debate around it. But on the contrary, I have seen how an overly-serious approach to a topic can turn an audience off before they even understand the complexity of the message that is intended to be delivered.

Whimsy is understood at multiple-levels of engagement, and can deliver a message to where the recipient ‘is now’, in their education, their context, their role, their age.

Bring on the whimsy! (but, as my daughters tell me, stop before you get the dad-jokes 🙂 ).

James Bonner, Tam Dean Burn, and Bill McGuire

about the writer

James Bonner

Dr. James Bonner is a Research Associate at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland. His interests and background are in a range of interdisciplinary research issues and themes including water, trees, place and mobility. He is particularly interested in the relationships between people and society to the places and spaces they inhabit and encounter.

about the writer

Tam Dean Burn

Tam Dean Burn has been a professional actor across platforms for over forty years and a performer, particularly of musical varieties, for even longer. He is also a very active activist in local, national and international campaigns. Most recently he has led a successful campaign to press Glasgow City Council to drop the plan for entry charges to the iconic 150 year old Kibble Palace in the city’s Botanical Gardens.

about the writer

Bill McGuire

Bill McGuire is an academic, activist, broadcaster, and best-selling popular science and speculative fiction writer. He is currently Professor Emeritus of Geophysical and Climate Hazards at University College London, a co-director of the New Weather Institute, a patron of Scientists for Global Responsibility, a member of the scientific advisory board of Scientists Warning and Special Scientific Advisor to WordForest.org.

Why does it have to be like this? Who gets to decide? Why, Why, Why?

The Whys of Whimsy…

A response from James:

What are the qualities of whimsy, of being whimsical?

Playful, fun, capricious, impulsive, wondering, wishful…

What is the opposite of whimsical?

Serious, staid, practical, definitive, steady, grave…

Can the gentle weapon of the whimsy, in conversation with the “serious science”, subversively critique the systems of social, ecological, and climate violence we find so hard to escape from, and disarm their power?

Whimsy opens up possibilities for playfulness and possibility. Letting go of what is “accepted” or “normalised”. It allows for imagination and questioning the structures in which we are bound by. Structures of the “big systems” like our economy and way places are designed. But also, by playing with the structures of language, writing, conversations, the stories we share and hold.

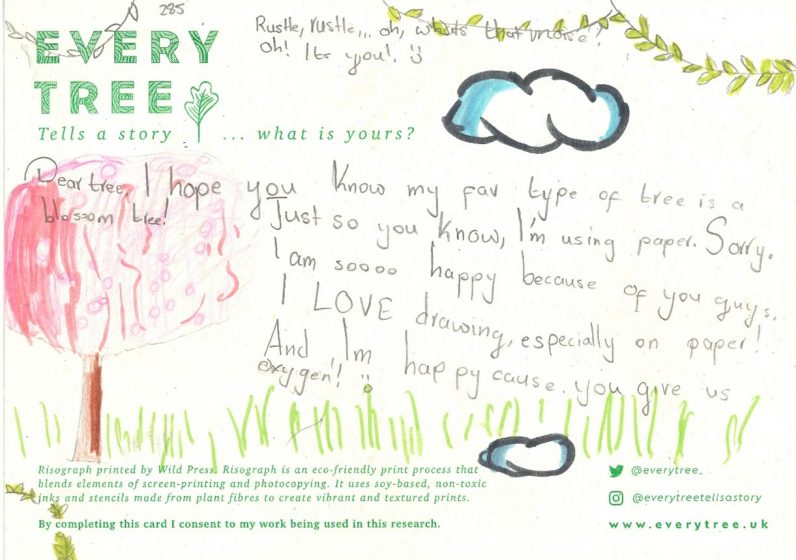

Climate conversations can be dominated by certain groups and narratives—academia, science, policy, industry. They are valuable and useful to inform the public and decision-making. However, this creates a focus on the “working age” population of “experts”, and it is their views and actions that dominate the narrative, and how we collectively react.

But what are voices that are not necessarily heard or included? Children, who have an openness and capacity to think and feel anew? Also, what for older people who have a memory of a world that has past, but can recall ways we used to do things? Can giving space for the whimsical help to engage with these groups and their perspectives—allowing for the playful imaginary of a different future from a child, while being attentive to a hazy recollection of something no longer here from an older person? Both perspectives of “wonder”, and a challenge to preconceptions and expectations of how, and why, the world has to be like it is now.

Whimsy and place: what are our places for? Could they allow for more fun for all ages? “Whether it’s a smile, a conversation, or just getting people to think about the issues in a new way, I think the impact justifies the effort”. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/crkd7861xgro

Whimsy and place: what are our places for? Could they allow for more fun for all ages? “Whether it’s a smile, a conversation, or just getting people to think about the issues in a new way, I think the impact justifies the effort”. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/crkd7861xgro

Can the gentle weapon of the whimsy, in conversation with the “serious science”, subversively critique the systems of social, ecological, and climate violence we find so hard to escape from, and disarm their power? Should we have more space for “why”?

James finds himself increasingly thinking about the ideas of play, for all ages, as fundamental to challenge ways we see the world, and how we might go about changing it. He often finds inspiration from how places are designed.

I’d suggest the most important question to look at with all this—and I do mean ALL—is WHY we laugh, the origins of laughter, and that is tied in with the origins of language and what made us human. There lies the key to understanding ourselves in nature.

A response from Tam:

The first thing I thought about comedy and climate was to contact the eminent climate scientist Bill McGuire as he has experience in this field and has written extensively about it, like here.

Bill and I have been looking to work together, and this looked like the opportunity at last. Bill was very positive about the idea and joined our email chat. But he was, of course, extraordinarily busy (not least in taking on Exxon in a court submission with a deadline the week before ours). Bill and I first met when I discovered his favourite film is “Local Hero” and I contacted him to say that’s the first film I’ve been in. A very whimsical film it is too, with a very ecological theme! I’ve suggested we look at making a new short cut of the film that offers something more to the situation we’re in now. Immediately, I thought off the top of my baldy head that one of my lines as Roddy the barman certainly rings afresh— “The Russians are coming!”. We’re going to look into that idea of a “Local Hero” new eco-edit, or some such description.

I also thought to look at master of whimsy Noël Coward’s songs and indeed there is “There Are Bad Times Just Around the Corner” which has much to offer. I’ve often rewritten song lyrics for greater pertinence in the past, and plan to with this, and found that it’s been done for a more recent American slant.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vaydfJzdGHk.

There’s also a wonderful eco-activist group “Ocean Rebellion” who are very big on visual humour that gains so much traction, and they happened to be holding their first ever exhibition just as I was passing through London very recently. We reacquainted and look to work together too. Here are examples of their work, and they were an inspiration for this critique I made of the aquaculture industry as an appeal to children— https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x7w2moy (there may be an advert in the middle, which is quite funny too! 🤑)

I’d suggest the most important question to look at with all this—and I do mean ALL—is WHY we laugh, the origins of laughter, and that is tied in with the origins of language and what made us human. There lies the key to understanding ourselves in nature, as part of nature and not just the disembodied, alienated creatures that patriarchal class society has made us.

That’s why we emphasised returning to lunar rather than solar cycles last time we took part in TNOC. And this knowledge can be found in the discoveries made by the “Radical Anthropology Group”. It’s not surprising that their forthcoming book on the origins of language is entitled “When Eve Laughed”. Here’s a talk on it . It’s all brilliant stuff but go to 45 minutes in for the beginnings of authors Chris Knight and Jerome Lewis looking at play and laughter and how essential that is to us and how it makes us human and capable of rising to the challenges we face. We must revel in the fun of solving this puzzle quoted from the draft of “When Eve Laughed”.

The real puzzle is to understand why humans became the first species strategically committed to suspending reliance on the senses in favour of faith in the benefits of laughter, imaginative social games, and the shared virtual realms to which they give rise.

Rob McDonald

about the writer

Rob McDonald

Dr. Robert McDonald is Lead Scientist for the Global Cities program at The Nature Conservancy. He researches the impact and dependences of cities on the natural world, and help direct the science behind much of the Conservancy’s urban conservation work.

Maybe the right way to think about whimsy is as a necessary first step. Much more than dry facts and figures on the return on investment of urban nature, whimsy motivates and inspires people to try new things.

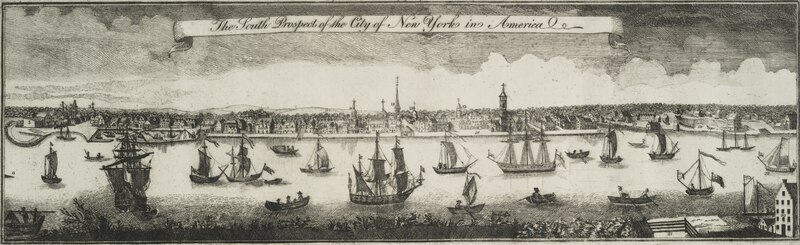

A lot of the most inspiring and fun ideas for nature in cities, or for the environmental movement more broadly, arise from whimsy. Over the centuries, humans keep inventing new roles for nature in cities, in ways that satisfy our needs and desires, whether utilitarian or playful. For instance, we now think of street trees as a commonplace idea, but there was a historical moment when cities in the Low Countries began to experiment with street trees. The Dutch had used trees to stabilize canal banks for a while, and since, in their cities, the canals came into the city center, it began to feel normal to extend trees to other streets. It is worth remembering the rest of the world viewed this intrusion of a natural feature into an urban area as a little bizarre, since nature was viewed as the untidy antithesis to the urban. But the odd, whimsical idea of a street tree met a need for shade and a little beauty, and the idea spread eventually (and thankfully!) to cities around the world.

Whimsy, in this broad sense, is the source of inspiration, of new ways of imagining what urban nature could and should be. We are in a period when humanity is demanding new and different things from nature in cities, including climate resilience and “mental health” and fashion, and this is leading to an explosion of whimsy from landscape architects and designers. Think of the fantastical Bosco Verticale in Milan, designed by the Boeri Studio to playfully maximize the amount of greenery on the facades and balconies. Or the new WOHO-designed Pan Pacific Orchard hotel in Singapore, which cuts out blocks of the buildings exterior to create large spaces for green parks, many dozens of stories above the streets below.

Whimsy is seductive, and a bit dangerous. Some of these whimsical green designs are expensive, high-end designs that are supposed to push the frontiers of ideas, making beautiful photographs that are widely spread and admired online, creating a brand name for the designers and building owners. But whimsical inspiration does not replace a plan for how to integrate nature more broadly into cities, in a way that is equitable and sustainable. Green roofs and facades are expensive propositions, and while there is a place for whimsy, there is also a place for nuts-and-bolts engineering and economics, of helping think about how to overcome the messy realities of (for instance) retrofitting existing buildings. These sorts of everyday projects will not be as whimsical or as exciting but are far more important to making urban green a reality for the majority of humanity.

Maybe the right way to think about whimsy is as a necessary first step. Much more than dry facts and figures on the return on investment of urban nature (the kinds of stuff I admittedly often produce!), whimsy motivates and inspires people to try new things. It is a first step, but other steps are needed to upscale nature-based solutions so that they can help any more people. For instance, it is important to realize that Singapore has so many green hotels because, in part, it has created a set of regulations that require new buildings to have a certain green fraction and creating strong government support for the construction of green infrastructure. Getting these kinds of enabling conditions right involves dry policy work, over many years, but it is also essential to go from whimsical idea to a widespread innovation.

Nic Bennett

about the writer

Nic Bennett

Nic Bennett (they/them) researches power, ideology, and belonging in science communication at The University of Texas as a doctoral candidate of the Stan Richards School of Advertising and Public Relations. They engage arts- and science-based research and practice to critique, disrupt, and reimagine science communication spaces. Alongside scientists, artists, activists, and community members, they hope to expand the circle of human concern in science communication and STEM.

We laugh at ourselves. We laugh at the oppressive systems. And that laughter does something significant.

A new student on campus struggles to speak up to a professor. A daughter of an immigrant mother confronts her on the environmental impact of cruises. Someone forgets their values while trying to impress a crush. These are all real moments from students’ lives that we put on stage. Moments where we made decisions that made us feel stuck. Moments we caused harm. Moments “voices” in our head gave terrible advice.

We often internalize the voices of our peers, our parents, and corporations. Sometimes, these messages are meant to protect us. Sometimes, they tell us we would be happier if we bought our way out of our climate anxiety. Often, we mistake these voices for our own.

To explore our struggles with environmental issues, we use a technique from Theatre of the Oppressed called Cops in the Head. Cops in the Head makes visible our internalized voices of oppression by making them into characters. We can rewind the tape multiple times and try out different scenarios. While we may not be able to shut these voices up or defeat them entirely, this form of theater explores how we might relate to these “cops” in new ways.

When we turn to face our emotions about the environment with theater, it can get heavy. We try to ensure this container is as safe as possible. We bring in eco-anxiety counselors. We build community trust and agreements.

When we turn to face our emotions about the environment with theater, it can get heavy. We try to ensure this container is as safe as possible. We bring in eco-anxiety counselors. We build community trust and agreements.

But a bit of silliness supports us as well. When we physicalize our voices of internalized oppression, we have them as clownish, exaggerated statues. They can move about and fling their barbs at us. They try to get us to do what they want, even when it goes against our values. If we listen to these “cops”, we can become stuck (freeze), collapse (flight), or lash out at others (fight). We turn to our trauma responses. But making them into characters affords us just enough space to pause. It allows us to examine the situation from a bit more distance. The “cops” can become silly to us.

The “cops” can be pretty silly, frozen in their stern postures. They might be cupping their mouth to shout at or pointing at us to get out of there. Because the “cop” is wobbling about like a statue and is a bit exaggerated, it gives us some breathing space.

The “cops” can be pretty silly, frozen in their stern postures. They might be cupping their mouth to shout at or pointing at us to get out of there. Because the “cop” is wobbling about like a statue and is a bit exaggerated, it gives us some breathing space.

Seeing a voice in our head as another character helps us get some distance. It helps us recognize that these stories are not ours. Getting multiple chances to intervene in a single moment reminds us of our responsibility and agency. We laugh at ourselves. We laugh at the oppressive systems. And that laughter does something significant. Where we were once ossified, we become limber.

We start to get unstuck. We see ourselves as able to transform and try new ways of being and relating. We often cry, but the tears are necessary. It means we are resensitizing ourselves.

We start to get unstuck. We see ourselves as able to transform and try new ways of being and relating. We often cry, but the tears are necessary. It means we are resensitizing ourselves.

It is normal to feel the enormous grief and anxiety of this moment. But it’s too much to hold alone, so we do this work together.

We face really, really hard things. We also goof off with one another. We poke fun at the clownish “cops” in our heads. We know we can’t shut them up completely, but we find new ways of relating to them, ourselves, each other, and the land. Laughter melts a part of us. It helps us become more like water and to slip into new fissures. When we laugh, we look up from our stuck postures. We notice the others around us. We reach for them.

Hita Unnikrishnan

about the writer

Hita Unnikrishnan

Dr. Hita Unnikrishnan is an Assistant Professor at The Institute for Global Sustainable Development, The University of Warwick. Hita’s research interests lie in the interface of urban ecology, systems thinking, resilience, urban environmental history, public health discourses, and urban political ecology as it relates to the evolution, governance, and management of common pool resources in cities of the global south.

To me―an urban scholar―this festival represents perhaps some of the most dramatic and whimsical examples of how engaging with urban nature can bring joy, hope, and a sense of romance.

When a Grebe, Kestrel, and a Frog spoke beneath a silvery moon

October 19th 2024. Parkwood Springs, Sheffield. A place I had the privilege to call “home” for over three years. An almost full moon shines over the site of a former urban landfill―one that was operational between 1970 and 2015; one so toxic to other local nature reserves that it had to be shut down. Next to this, on a grounds formerly occupied by a deer park, over a 1000 people adorned with fairy lights, some of them with equally decorated dogs in tow, walk slowly―to the tune of two local Samba bands (the Sheffield Samba Band and the Sheffield Youth Samba Band) under the silvery moonlight, each with a willow lantern shaped like a bird or animal. The pièces de resistance are three giant lanterns lighting up the night―a magnificent kestrel, its beautifully decorated lit wings held aloft and flapping in the night, one of the leading artists Patrick Amber (the other being Jo Veal)―dressed and lit up as a great crested grebe, and a reclining Amalie―the beautifully decorated frog. To a casual onlooker, it is almost as if three giant, mystical representatives of the avian and amphibian worlds are speaking an ancient language known only to them.

All along the path taken by this lively procession are other equally whimsical lantern creations―a Viking longboat, reindeer, dragons, bluebells, sunflowers, and other entities too whimsical to endow with a name or shape. Each lantern is carefully conceptualised, designed and handmade by local artists Patrick Amber and Jo Veal, together with The Friends of Parkwood Springs (a local collective that serves to protect and increase the visibility of this urban space), and members of the community through a series of workshops open to anyone with any level of talent and held a few weeks before the event itself.

To me―an urban scholar―this festival represents perhaps some of the most dramatic and whimsical examples of how engaging with urban nature can bring joy, hope, and a sense of romance. First, there is the site itself. To someone new to the region and walking the many acres of land covered by Parkwood Springs, it is hard to believe that this was once a site that epitomised hostile, toxic facets of urban nature relationships. Today, it is a dramatic and seasonally changing landscape filled with grass, woodlands, heather, gorse, brambles, and―if you are lucky―the occasional herds of deer frolicking in the sunset. Almost every fortnight on a full moon here, a dystopic look out through which you can gaze for miles across this hilly city transforms dramatically. For on those days local artists and members of this tightly knit community come together for a night of shadow puppetry, music, dance, dog walking, and other forms of community building―under the light of the moon, and with giant community-made lanterns representing some element of the season in question―bluebells, for example.

And then there is the lantern festival itself. Nothing screams romantic and whimsical more than the sight of hundreds of lanterns bobbing up and down as their bearers walk past, the lanterns homogenizing people into an indistinguishable mass of humankind―united under the light of that silvery moon. While invoking a sense of fun, nostalgia, and community―with an enticing bit of whimsy, these events are also a way of reconnecting with the nature around, of appreciating what the spaces around us can give us, and of giving back. Giving back to nature through co-creating appreciation and joy, enabling a renewed interest in engaging with such spaces, so enhancing their value, and aiding their preservation for future generations. As Robert Macfarlane says in his Landmarks, “What we bloodlessly call ‘place’ is to young children a wild compound of dream, spell, and substance: place is somewhere they are always ‘in’, never ‘on’.” Parkwood Springs, and the activities there, continue to give to its inhabitants―its present, and future generations―that sense of connection by giving substance to dreams and weaving hopeful spells for the future. To me, these are visions of an alternate way of engaging with nature and the massive challenges we face―beyond the more common visions of doom and gloom and into a renewed sense of hope.

Emmalee Barnett

about the writer

Emmalee Barnett

Emmalee is a writer and editor with a love of nature and stories. She is the editor of TNOC’s magazine and various fiction projects and the Co-director for NBS Comics. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Literature from Missouri State University and currently resides in the tiny town of Spokane, MO.

The general public’s eyes will glaze over a poster declaring we need to “save our earth”, but they’ll shutter and pause if that poster has a silly ladybug in a superhero costume.

When I think of “whimsy”, my mind immediately wanders to the strange, the fantastical. Stories such as Alice and Wonderland, The Little Prince, and Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series where the impossible is possible and nothing quite makes sense. There’s a sense of randomness that everyone takes on board and rolls with. The path of logic is there, it just didn’t end where you expected it to due to a few wrong turns and a sideways explanation.

A lot of people seem to forget that ideas like “whimsy” and “wonder” can be applied to everyday life, especially everyday work life. If you get into the right mindset, there are ways to add a dash of whimsy to anything. It can be anything from adding fun colors to a spreadsheet, making graphics more abstract, or using an “out there” theme for your latest project proposal; there are countless ways to add whimsy to anything work-related. If people don’t get it, then that’s their fear of sticking out and trying something different raising its ugly head. Thinking about the absurd is also a good way to wrap your ever-expanding mind around what whimsy encompasses. Things that are a little off, not within the norm.

Working with NBS Comics, I’ve been introduced to many different, some might say whimsical, ways to negate climate change and the challenges the environment faces. I mean, we’re making comics to help raise awareness of Nature-based Solutions. That’s pretty whimsical to most “serious” practitioners. I believe it takes thinking “outside of the box” (what’s in this box, we’ll never know) to create new nature-based solutions; ways and projects no one has tried before. It also takes these approaches for people to care about such projects. The general public’s eyes will glaze over a poster declaring we need to “save our earth” with a drawn globe, but they’ll stutter and pause if that poster has a silly ladybug in a superhero costume on it.

It’s the small things we can start with to sprinkle more whimsy into the science world.

Claudia Misteli

about the writer

Claudia Misteli

Claudia is a social designer, communicator, and journalist who believes that care, creativity, and collaboration are key to building more just, vibrant, and nature-connected places. Born between Colombia’s coffee region and the Swiss Alps, she now lives in Barcelona, blending cultures and perspectives in her work. At The Nature of Cities, she co-leads European projects and TNOC Festival, sparking connections and meaningful action. Claudia also volunteers with the Latin American Landscape Initiative (LALI), helping amplify regional voices and build bridges across Latin America through storytelling, communications, and a deep love for people and place.

The serious power of whimsy

In Colombia, we often say, El que no llora, no mama—if you don’t cry, you won’t get fed. But I’d better say, El que no ríe, no aprende—if you don’t laugh, you won’t learn.

Being half Swiss and half Colombian always made me straddle two cultures—Switzerland’s orderly landscapes and Colombia’s vigorous natural beauty—I learned to find magic in contrasts. My Swiss side loved the precision of alpine wildflowers, neatly arranged as if they were posing for a photoshoot. My Colombian heart, meanwhile, danced to the anarchic symphony of the green parrots squawking when the rain came down from the Andes mountains. Whimsy was not just an occasional visitor; it’s always been part of who I am, weaving stories that helped me bridge these two completely different worlds.

Today, as we stand at a kind of precipice of the climate crisis, biodiversity loss, and political uncertainty, I ask myself: Can whimsy serve a purpose in our most pressing global, local, and personal struggles?

Imagine an aquatic field of Posidonia (Posidonia Oceania) waving tiny fans. (Why? To cool off as the ocean heats up, of course!). Or designing a crowdfunding campaign to save urban frogs titled “Give me a kiss and I give you back a prince”, where every donor receives the chance to “Kiss a Frog” challenge kit as an incentive. I think these ideas are not so silly at all; they’re strategic. Whimsy can slip past defenses, melt skepticism, and invite people into spaces they might otherwise avoid.

These heavy topics—climate change, biodiversity loss, environmental justice—often weigh too much for hearts already burdened or disconnected from these issues. But whimsy lifts, making it easier to carry.

Laughter is a shortcut to understanding

Take the example of the cotton-top tamarin, a tiny primate found only in Colombia, with its wild, fluffy white mane that looks like it’s perpetually having a bad sleeping night. Its whimsical appearance contrasts with the stark reality of its critically endangered situation, threatened by habitat loss and the illegal pet trade. Imagine a meme of a cotton-top tamarin with the caption: “When you wake up late but there’s no time to snooze when extinction is near”. Humor and whimsy don’t trivialize; they humanize, creating cracks in the walls of indifference where empathy can slip through.

In Colombia, we often say, El que no llora, no mama—if you don’t cry, you won’t get fed. But I’d better say, El que no ríe, no aprende—if you don’t laugh, you won’t learn. With its power to delight and surprise, whimsy can turn passive observers into active participants, bringing critical issues closer to the hearts of those who might otherwise look away.

Whimsy as a love language

One plant always stood out to me—the Alocasia, the Elephant’s Ear. But to me, always the Heart Plant. Its leaves, shaped like perfect hearts, seemed to pulse with a clear message: I love you. I still do not see those plants as just greenery; they are messengers sending quiet but profound signals of care, tenderness, and connection.

Whenever I encounter an Alocasia, a love letter from nature is etched in my heart. It’s a reminder that nature has been reaching out to us all along, expressing its love through intricate designs and quiet gifts. And now, I feel it’s our turn to reciprocate.

Can we write back to nature a love letter? What if our climate or NbS campaigns included love letters for glaciers or matchmaking services for lonely urban trees willing to give shadow?(Swipe right for the tree with excellent shade!) These small, whimsical gestures are not distractions; they are acts of re-enchantment, rekindling our sense of wonder.

So let’s dance with nature, tell her jokes, make some memes, and write poems or love letters. Maybe, just maybe, whimsy will save the world—or at least make the effort a little more fun.

Elizabeth Frickey

about the writer

Elizabeth Frickey

Elizabeth Frickey (she/her) is a Ph.D. student in musicology and MacCracken Fellow at New York University. Her current research examines the cultural, ecological, and political impact of community gardens and other urban greenspaces through the lens of music and sound.

Whimsy Is in the ear of the beholder

How could the presence of a keytar in a community garden be anything but whimsical?

You’re walking down Houston Street on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, New York City on a brisk Sunday afternoon. The busy throughway, with its four lanes of traffic, thrums with the usual sounds of wheels on pavement, distant sirens, and the voices of fellow pedestrians in jovial conversation. Seeking respite from the urban thrall, perhaps you stroll towards the nearby First Street Garden. However, as you approach, you are met not with the quiet you were seeking, but something else entirely. You aren’t even quite sure what you hear… there’s a mournful wailing sound… or a mechanical tapping sound met with a ghostly whirring… or is that a noise rock band playing around the corner?

I like to imagine the number of people to have had this exact serendipitous experience―to have paused at the fence separating the garden from the bordering sidewalk, surprised to find, not a secluded space of peaceful refuge, but a free jazz concert unfolding before their very eyes and ears. This is not an isolated experience, however, but merely one of the many iterations of the Arts for Art annual InGardens Festival which you have stumbled upon.

As a musicologist, I am often drawn towards networks of urban ecologies first and foremost through my ears. In the context of the InGardens Festival, for example, I wander into this space, wondering:

Why does this cacophony of free and raucous improvisation exceed my expectations for the garden’s soundscape, and am I alone in this impression? What do I imagine the idealized urban greenspace to sound like?

Formally founded in 1996 by dancer and poet Patricia Nicholson, Arts for Art (AFA) is, per its mission statement, a New York-based nonprofit organization dedicated to “the promotion and advancement of FreeJazz―an African American indigenous art form in which improvisation is principle.” For those familiar with the characteristically jagged and unpredictable sounds of experimental free jazz as a genre, the garden environment might come as an unexpected venue for this style of music. It is in its evasion of my sonic expectations that the InGardens Festival thus becomes whimsical to my ears. Indeed, how could the presence of a keytar in a community garden be anything but whimsical?

But then, from my vantage point in the comfort of this greenspace, I hear the high-pitched chirps of a song sparrow, and I swear the flutist in front of me chirps back in response. Helicopter blades chop overhead in time to the harsh tremolo of the double bass. A drummer catches the tac-a-tac-a-tac of the jackhammer on the other side of the fence. A saxophonist lays down their horn and yet, the music continues. I cock my head. Was it there all along?

Perhaps the power of the InGardens Festival, of the keytar in the garden, is not derived solely from the improvisations of human musicians, but also from the improvisational response of the more-than-human. If free jazz pokes holes in our conceptions of what music even is in the first place, the boundaries of music/noise, backdrop/performance, human/more-than-human become blurry to the point of indistinguishability. The garden itself is more porous than we once thought …

And yet, the whimsy remains. Newly attuned to the music of the urban greenspace–as loud, messy, and, yes, capricious as the free jazz which it had accompanied–we hear differently now. I laugh at myself for ever thinking the garden would be so sonically submissive, for thinking that I could be so easily separated from the garden myself.

I whistle along.

Wendy Wischer

about the writer

Wendy Wischer

Wendy Wischer is an artist and educator currently living and working in Connecticut. With investigations in a variety of media from sculptural objects to installations, video, projection, sound, alternative forms of drawing and public works. Much of the artwork is based on blurring the separation between an intrinsic approach to working with nature and the cutting edge of New Media.

What a Wonderful World (Louis Armstrong)

This Land is Your Land (Woody Guthrie)

If I Had a Hammer (Peter Paul and Mary)

Imagine (The Beatles)

Will the Circle be Unbroken (June Carter Cash)

Where Have All the Flowers Gone (Kingston Trio)

Fire and Rain (James Taylor)

Wind Beneath My Wings (Bette Midler)

Candle in the Wind (Elton John)

I Will Remember You (Sarah McLachlan)

Lay me Down (Sam Smith)

Hallelujah (K.D. Lang)

Heaven (Beyoncé)

Supermarket Flowers (Ed Sheeran)

Tears in Heaven (Eric Clapton)

My Heart Will Go On (Celine Dion)

Here Comes the Sun (The Beatles)

I Feel the Earth Move (Carol King)

All is Full of Love (Bjork)

I Will Always Love You (Whitney Houston)

Chris Fremantle

about the writer

Chris Fremantle

Chris is a researcher and producer working across environment and health. His research focuses on the pioneering ecological artists Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison who he also worked with. He is currently exploring artists’ projects with trees, woods and forests. Chris is a Research Associate with TNoC’s naturePLACE supporting evaluation approaches.

Whimsy is adopting the ridiculous and taking it seriously.

Earnest is probably the opposite of whimsical. Climate change, nature-based solutions, the planetary crisis: they are all enormous and require earnest attention. Whimsy has perhaps two aspects. Firstly, it always exists in the face of overwhelming seriousness. Lord Peter Wimsey, Dorothy L. Sayers’ fictional detective subject of eleven novels, is the epitome of whimsey in the face of murder. His intentional, even affected, lightness is in the face of experiences as an officer in the First World War which have left him suffering what was called “shellshock” then and PTSD now. One of the other critical responses to the horrors of the First World War was Dada, the absurdist art movement. Being whimsical in the face of the planetary crisis might seem to be an absurd response, but the lightness allows for imagination, and the other key characteristic of whimsey is fancifulness. This invokes the possibility that there might be an alternative, albeit seemingly an improbable one. Whimsey’s fancies are by definition implausible (just as Wimsey’s solutions to the crimes appear implausible to start with).

We need to confront the horror of the planetary crisis, including how we are all bound into it through, not least, our dependency on ever-increasing energy supplies, and our disposable culture. But we also need to be willing to imagine our way to a different culture, one where exchange is the organising principle rather than consumption. The artists Helen and Newton Harrison framed this in terms of “putting back more than we take”―perhaps somewhat fanciful when we think about fossil fuels and plastics!

Design-thinking practitioners have developed some useful tools which can help with getting into the state of mind to be whimsical and fanciful. One is the Fast Idea Generator. Nesta, the innovation organisation that developed it, describes it as a tool to develop an existing idea by looking at it from a number of perspectives. Having used this tool, one of the things that is apparent is that for it to work, participants need to get into a somewhat whimsical state of mind. The tool can help, but like whimsy in general, it isn’t a solo state―everyone needs to be willing to participate. The tool asks you to do several things to your idea―to twist it and distort it. The tool says things like―invert the idea, exaggerate the idea, translate the idea to completely different circumstances. In this last case it means something like designing hospitals as if they were airports. This has been done and it does mean people get to their clinic waiting area (aka, departure gate) very efficiently! Whimsy is adopting the ridiculous and taking it seriously.