The intertwining of social identity, emotional attachment, and environmental stewardship highlights the complex yet vital role that love plays in fostering a sustainable and just urban future.

Love, a complex and profoundly influential emotion, has been widely explored in a variety of academic fields including sociology, psychology, anthropology, as well as human and physical geography. In geography, love is explored in several ways, including love of place and of nature (tophilia and biophilia) (see Tuan, 1974 and Wilson, 1986, Faggi, 2024). Love is also a vital component in achieving social and environmental justice as a means of promoting action (Hall, 2019; Jacobsen et al., 2019). Godden and Peter in their 2023 article emphasise that love assists activists in understanding the complex relationships and interconnectedness amongst humans, and between humans and nature, focusing on activism, justice, and well-being for all species. This essay is based on extensive qualitative research as part of my PhD project and will focus on the intersections of love, nature, and social justice within Nottingham, a medium-sized city within the East Midlands region of the UK.

Nature in Nottingham

Nottingham’s physical environment helps residents shape place attachments and meanings and is an important asset for the city in terms of tourism and community well-being. The natural environment does, however, pose potential hazards in terms of flooding and heatwaves. For example, the 2022 record-breaking heatwave caused great stress for many of the city’s residents, especially those without access to places to cool down (see Ogunbode report). The duality of our bio-physical environment also conjures a plurality of emotional responses, with Segal (2023) suggesting “nature is often prized as inherently nurturing, offering us moments of solace and beauty… for others, unmitigated nature is usually scary, a place arousing dread and foreboding” (p.156). Grappling with nature’s ambivalence is a challenge for urban planners, practitioners, and scholars, given the typically positive framing of urban nature-based solutions and urban green infrastructure.

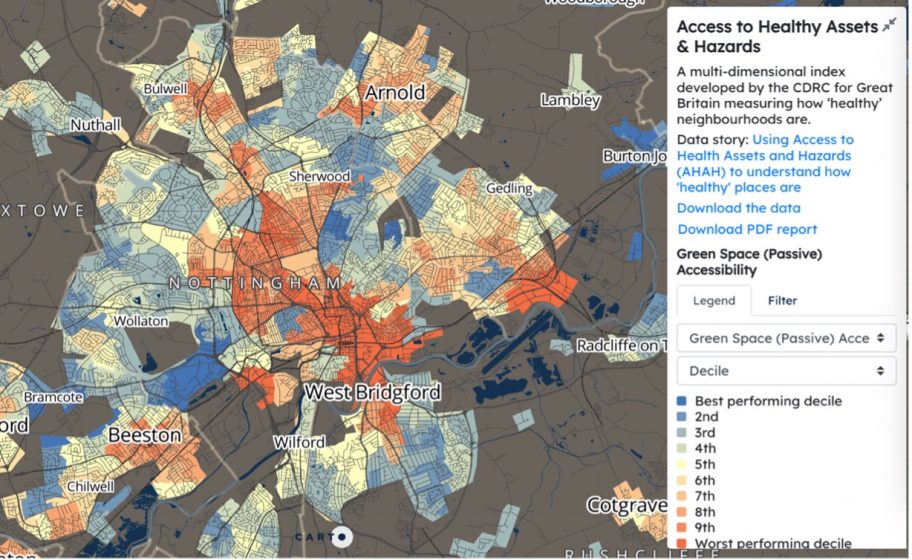

Nottingham is a particularly ‘green’ city―in 2023, the UK Ordinance Survey ranked Nottingham as the 8th top city in terms of access to public green space (20.68% coverage). The city also boasts 71 Green Flag Awards (an international mark of park quality)―more than any local authority area in the country outside of London (Sloam, Henn, and Huebner, 2023). Despite this extensive network of green space, inequality in access, as found in many cities globally (Wüstemann, Kalisch, and Kolbe, 2017; Maddox, 2017; Williams et al., 2020; Pickett, 2022), does persist within Nottingham (figure 1). These areas include Bulwell, Bulwell Forest, and Bestwood, which are classified as deprived areas in the north of the city centre (IMD, 2019). Other areas of deficiency to the west of the city centre include Bilborough and Wollaton West. The Council, in their 2021 open and green spaces audit, cite several barriers to access including large roads (Nottingham Outer Ring Road, A60), railway lines, canals, and rivers. Indeed, one interviewee reflected that “there is a lot of green space, but access to it is really inequitable and if you look at a map of the green space, it’s concentrated in certain areas and some of the more deprived areas haven’t got their fair share”.

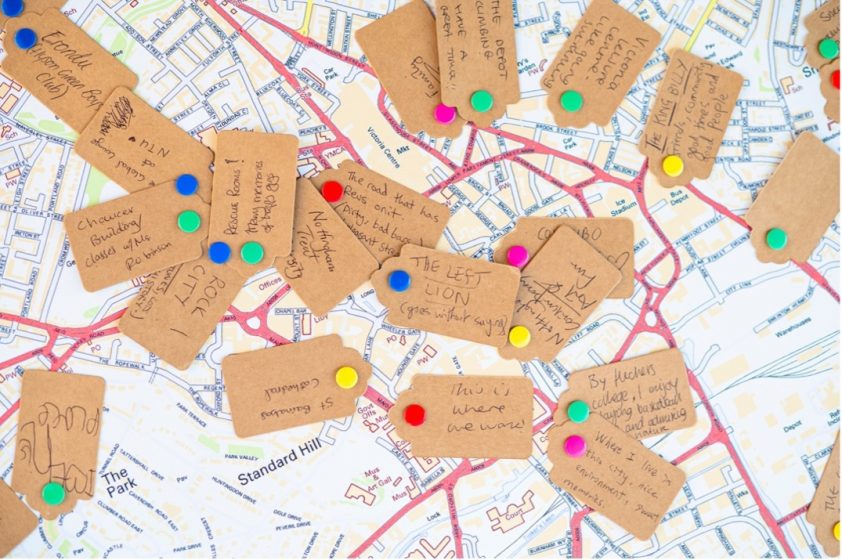

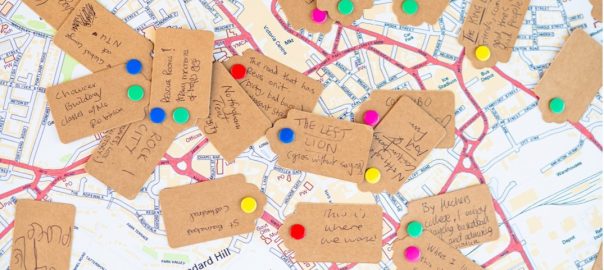

Access to green space is important to communities in Nottingham, highlighted by collaborative mapping exercises conducted as part of this research (figures 2 and 3). When prompted to pin places they loved within the city and county, green spaces were the most common answer for a variety of reasons including walking, relaxation, and socialisation. This deep love for green space reflects not only a connection to nature, but also highlights how green space can help build a sense of community, identity, and shared well-being. This affinity for nature is not merely passive but is actively expressed through involvement in stewardship and activism, with numerous community groups becoming involved in maintaining and enhancing streets, parks, gardens, and allotments. The importance of and love for green space in the city is further mirrored by top-down and grassroots initiatives.

Prior to public consultation, Nottingham’s Carbon Neutral Action Plan (which is part of the CN28 initiative where Nottingham is aiming to become the first carbon-neutral city in the UK by 2028) was wholly focused on carbon reduction, mitigation, and adaptation. However, during various engagement events, the council realised that there was a strong demand from the community to also focus on nature and green space, adding a whole section on ecology and biodiversity. This section highlights how a focus on nature can provide a series of co-benefits for the city and its residents and takes a more holistic approach to sustainability than focusing on carbon emissions alone, focusing on carbon storage in soils, provision of food and water, reduction of flooding, cooling as well as benefits of nature for human health and well-being. While a more top-down approach, the success of CN28 hinges on the participation and collective efforts of residents, businesses, and local organisations, creating a symbiotic relationship with grassroots groups and charities in the city, encouraging all stakeholders to take an active role in protecting and enhancing Nottingham’s natural environment.

Indeed, community-led, grassroots efforts play a crucial role in shaping Nottingham’s natural environment and promoting environmental concerns. As Brieger (2018) highlights, place-based social identity significantly influences environmental concern. When interviewed, one Nottingham resident expressed, “It’s my area. I love this area. Why would I want to see all the litter and the rubbish?” and went on to explain how this love for their community motivates them to take action, regularly participating in litter picks and clearing overgrown areas, as for them, being part of the community means actively caring for and nurturing it, driven by a sense of responsibility and pride. These emotional responses are, however, subjective and not universal, as not all members of the community feel the same sense of love and responsibility, which creates tension and can lead to other emotional responses such as anger.

Beyond individual action, collaborative grassroots events like the Green Hustle festival, self-described as “a celebration of life and creativity that aims to make our city greener, healthier, and more connected”, sought to challenge the perception that environmentalism is not for everyone, aiming to make the movement more inclusive by creating a festival focused on various strands of sustainability. One of the festival organisers emphasised:

“I think representation is really important, just showing people from all walks of life doing positive things and taking part in something that speaks to them…We’re going to be doing lots of green stuff… but it’s a festival about food and fashion and sport and travel and all these things that everybody does or that all matter to somebody. It’s about connecting with people, meeting them where they’re at on climate change”.

This holistic approach aimed to resonate with a broader audience, offering entry points for engagement that aligned with their personal interests and values. By intertwining environmental concerns with everyday activities, the festival hoped to create meaningful connections and foster dialogue, encouraging collaboration among individuals who might not typically consider themselves part of the environmental movement. The legacy projects from the festival have also created numerous urban green spaces in the city, including on Market Square, Sneinton Market, Bridlesmith Gate, and Wilford Street Ramp, leaving a lasting impact on the city and allowing more people to interact with nature daily. This interaction helps to expand and grow love for nature and the environment in the city, promoting sustainable and green urban solutions.

Another landmark grassroots effort was the promotion of a “Green Heart” (a prime example of how green space in the city helps to cultivate love) in place of the old Broad Marsh shopping centre (Figure 4). The campaign began as a grassroots movement with over 11,000 residents supporting a petition to transform the disused shopping area into a restored marsh and green space. This overwhelming community support captured the attention of the city council who recognised the importance of community input, who responded by launching a wide-scale public consultation called “Broad Marsh: The Big Conversation”, which invited residents to share their visions for the redevelopment of the Broad Marsh site. The consultation, which received over 3,000 responses, was a clear reflection of the collective commitment to enhancing the city’s natural environment. This process not only highlighted the residents’ passion for integrating nature into urban spaces but also showcased a successful example of participatory planning, where the voices of the community directly influenced city policy and planning decisions, much like they did in the CN28 plan. As a result of this collaborative effort, the city council has now committed to and started work on a new area of green space within the city centre. The ‘Green Heart’ initiative shows the power of collective action and illustrates how grassroots activism can align with and enhance top-down urban planning, leading to outcomes that reflect the desires of communities.

The deep-rooted love for nature within Nottingham’s community serves as a powerful force in shaping the city’s environmental landscape. Whether through top-down initiatives like the CN28 plan or grassroots efforts such as the Green Hustle festival and the Green Heart campaign, this collective passion for green spaces drives both individual and communal actions. Here, love moves beyond a sentiment, forging action and advocacy as well as a collective commitment to nurturing a “greener” future, shaping the spaces and places in which people connect to the city and one another. The intertwining of social identity, emotional attachment, and environmental stewardship highlights the complex yet vital role that love plays in fostering a sustainable and just urban future.

about the writer

Chris Ives

Chris Ives takes an interdisciplinary approach to studying sustainability and environmental management challenges. He is an Assistant Professor in the School of Geography at the University of Nottingham.

Katie Keddie and Chris Ives

Nottingham

Leave a Reply