Biodiversity has always been important to environmental scientists, conservationists, landscape architects, and others but only recently seems to have entered the public domain. It took a long time for Australia to accept the climate emergency. It is pleasing to see that the biodiversity crisis has been accepted more readily. There is legislation at national and state government levels, and policies, strategies, and operational procedures in many local municipal councils to guide the protection, enhancement, and conservation of biodiversity.

What do these tasks entail in Australia? How will the landscape of Australian cities and towns change as landscape architects and designers prioritise biodiversity in their work? How are Australians likely to respond to these biodiverse urban landscapes?

Protection, enhancement, and conservation of biodiversity sound like straightforward activities in themselves but driving each are a philosophy and a value system. This is reflected in the terminology adopted when considering biodiversity in cities in Australia. Around the world, the term “rewilding” has gained prominence. In Britain, rewilding is defined as “the large-scale restoration of ecosystems to the point where nature is allowed to take care of itself. Rewilding seeks to reinstate natural processes and, where appropriate, missing species―allowing them to shape the landscape and the habitats within. It’s focused firmly on the future although we can learn from the past”. There are five principles: support people and nature together, let nature lead, create local economies, work at nature’s scale, and secure benefits for the long term.

In Australia, “rewilding” is a problematic term because of unacceptable connotations for First Nation Australians. Rewilding aspires to return land to its natural uncultivated state. However, the Australian landscape has been managed by its indigenous inhabitants for tens of thousands of years and so cannot be considered wild in the recent past. At federal level, legislation addressing biodiversity uses the term “nature positive”. This has not been adopted at state level, however. For example, the New South Wales government has proposed the term Biodiversity in Place when developing a framework for urban biodiversity. Other terms used in Australia are Biodiversity Positive Design, by the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects, Nature Positive Design and Development, in work by Griffith University in Queensland, and Biodiversity Sensitive Urban Design, by researchers at RMIT University in Victoria. Each adopts a different approach to protecting, conserving, and enhancing biodiversity in Australian cities but all respond to the impacts of urbanisation on biodiversity, i.e., climate change, land use change, pollution, exploitation of natural resources, and invasive species. The dilemma is that cities contribute to the loss of biodiversity yet require biodiversity to survive.

Sustainable development has generally emphasised the triple bottom line: environmental, economic, and social. Laura Musacchio suggested that the bottom line for sustainable landscape design is more likely to have six attributes: environmental, economic, equitable (environmentally just), ethical, experiential, and aesthetic. Of these, the aesthetic attributes of a landscape are often overlooked when its sustainability is considered. Yet, the ecosystem services of a landscape include its aesthetics and there has been much research into landscape perception that also suggests their importance.

Sustainable landscapes must be visually appreciated by the public in order that they are supported, cared for, and survive.

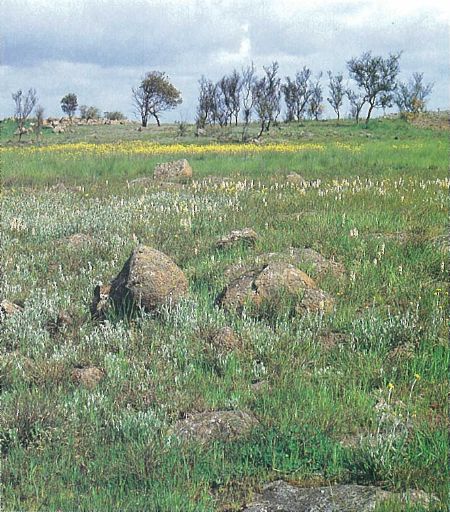

Therein lies a problem with creating biodiverse landscapes in Australia. The aesthetics of many of the indigenous plants can be difficult to appreciate. Certainly, some of the flowers are spectacular, such as grevilleas, banksias, callistemons, and acacias, but many plants have quite small and inconspicuous flowers. The flowering meadows that result from rewilding in England are almost an impossibility here. For example, vast grasslands covered the volcanic plains of western Victoria, in south-eastern Australia, before it was colonised by Europeans. These had been managed with fire-stick farming by the local aboriginal tribes to create landscapes that would support hunting and gathering. The dominant plants were tussock grasses with small herbaceous plants with tiny flowers in the gaps between them. Such grasslands do not compare aesthetically with the colourful flowering meadows of England. Tussock grasses are widely used in sustainable systems that use plants to treat contaminated stormwater, e.g., raingardens, and studies have shown that they are often perceived as unattractive and untidy. To plant extensive areas with native grassland to enhance biodiversity in urban areas might not be accepted aesthetically.

Here is the nub of the issue: context is critical when undertaking a biodiversity project. Is the intention to protect biodiversity, enhance it, or conserve it? Protection and conservation of biodiversity imply that existing landscapes are already biodiverse. The task of protection or conservation then seems relatively straightforward. The challenge lies in enhancing biodiversity. What this entails will depend on the context.

Back in 1939 and 1940, three eminent landscape architects, Garrett Eckbo, Daniel Kiley, and James Rose, described three different contexts for landscape design: primeval, rural, or urban. Each required a different approach but each centred on designing for the landscape’s inhabitants. In the primeval landscape, the inhabitants are the “beasts, birds, insects and plant life”. In contrast, humans are the inhabitants of the rural and urban landscapes. This distinction should guide the creation of biodiverse landscapes. The focus must be on the flora and fauna of primeval landscapes but in rural and urban landscapes the needs of humans must also be considered. The aesthetics of the landscape are especially important when designing sustainable landscapes for human use. Meeting biodiversity and aesthetic needs in an urban landscape is a special challenge in Australia.

In conversations that I have had, a common assumption has been that biodiverse urban landscapes must comprise indigenous and endemic plants that occurred in those areas before white colonisation in 1788. The aesthetic shortcomings of many of these species in Australia are an immediate problem. Another is the shift in climate zones because of climate change. The plant communities that existed at a site in a modern Australian city might no longer be able to survive without intensive management. Such management might be possible but could be at odds if the goal of sustainable biodiverse urban landscapes is to provide minimal maintenance after establishment. Exploring this issue of plant selection and ecosystem structure in the academic literature is as fascinating as the definition of biodiversity itself, which I wrote about in a previous essay. For my purposes here, Eric Higgs’ work is useful. He distinguishes self-assembled and designed ecosystems. Self-assembled ecosystems can be historical, restored, hybrid, or novel. These four states, in a sense, form a continuum, differentiated by the degree of intervention, requirements for ongoing maintenance, the strength of historical composition and processes (i.e. historicity), and ease of reversion to the original composition (see Higg’s Table 1).

Higg’s describes novel ecosystems as arising “through initial, sometimes inadvertent, human disturbance, but develop over time to form new, metastable conditions in response to new mixes of species and environmental conditions”. Designed ecosystems can be reclaimed landscapes or designed for a particular function to deliver specific ecosystem services, e.g., green infrastructure. The management intention for self-assembled ecosystems is ecosystem-centred, and human-centred for designed ecosystems. Thus, designed ecosystems should be the objective when creating biodiverse urban landscapes for their human inhabitants. Such designed landscapes will include the biotic, abiotic, and social components required to deliver the desired ecosystem services.

In the case of plants, these could be indigenous, native, or exotic. Plant selection must respond to the project brief, the functional objectives for the landscape, and evidence-based aesthetic preferences. Such designed ecosystems should include a rich variety of plants, as a basis for biodiversity. These plants should be selected for both their technical function within the ecosystem and their aesthetic function for urban inhabitants. The landscapes will require maintenance to ensure the delivery of the intended ecosystem service. However, as Higgs illustrates in Figure 2, novel ecosystems are the trajectory from designed ecosystems to self-assembled ecosystems. Thus, in time, a biodiverse-designed ecosystem might develop into a novel ecosystem and ultimately be self-maintaining.

Biodiverse urban landscapes must be attractive, visually appealing, and appreciated by the community. Only then will they be valued and cared for, which is required for their long-term survival in our cities. Many of the indigenous plants of Australia pose aesthetic challenges. However, urban landscapes based on designed ecosystems with a mix of indigenous, native, and exotic plants should achieve the objective of biodiversity.

Meredith Dobbie

Victoria

Add a Comment

Join our conversation