It can be easy to remain in the bubble of your own perspective, thinking that one’s relationship to place might be a universal phenomenon. When the phenomenon, in fact, is the uniqueness of each person’s relationship to place, community, home, and their perspectives, cultures, and lived experiences that shape the relationship.

This realization has been forming over the last 10 years as I’ve grown, stepped away, and once again returned to the rural town I was raised in.

To provide some background on myself, I am a European-descended settler who grew up in the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York, USA. My summers were filled with camping, hopping on rocks in the Sacandaga River, and taking trips to visit my grandparents’ home where their garden would feel like magic as the sunlight backlit the many flowers and trellising beans they grew. My connection to this place is strong and I have experienced both heartache and joy as I’ve seen my local landscape change over time.

Growing up, my early understanding and generalization of human relationships to the natural world was that overconsumption and exploitative practices were ubiquitous and the principal relation to exist as shown through resource wars, both current and past, as well as the need for large-scale remediation efforts to mitigate the polluted land and water resulting from this greed. Frustration and the desire to “do better” was my gateway into the practice of ecological restoration.

It was during my undergraduate studies in ecological restoration at Paul Smith’s College that I began to realize how myopic my view was. Paul Smith’s College, known as the “College of the Adirondack”, is located northwest of Lake Placid, near the high peaks region of the Adirondack Mountains of NYS. It is a school that prides itself on its learn-by-doing educational model that uses the surrounding lands and waters as a living-learning lab that uniquely offers courses in both natural science and forestry as well as culinary arts. It was here that I began to learn about the networks that connect and sustain ecosystems and the interdependent life contained within them through exploring the forests and wetlands. I also learned that the erasure of traditional, cultural practices, and lifeways from landscapes have caused degradation and decline in ecosystems. And as a result, the restoration of those practices on the landscape can be healing for the land, water, people, and other living beings. The key for successful restoration projects, as was stressed by Craig, my academic advisor and professor, is the integration of people and community into all parts of a project, to ensure stewardship into the future. Through this education, I began to see the biocultural mosaic, or the many human relationships and cultural traditions connecting people, plants, animals, fungi, and place, on a landscape.

After the COVID-19 pandemic subsided in the United States, I returned to university to pursue my interest in the networks of relationships that sustain people, culture, and other forms of life through a master’s degree at SUNY ESF. My research focused on seed dispersal relationships and their influence on sustaining the traditional agroforestry system practiced by the Lacandón Maya of Southern Mexico. A foundational aspect of this research was learning from traditional knowledge holders. That experience had a profound impact on me. It strengthened my respect and appreciation for biocultural practices so inextricably tied to place through language, those that both lend resilience and vulnerability to global changes.

Most recently, I have been working as a Resource Assistant intern with the USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station’s New York City Urban Field Station helping with their stewardship programming including the Stewardship Salons.

Stewardship Salons are nurturing spaces for diverse voices in natural resource stewardship and care for those who wish to collaboratively learn and build community with one another. Salons are a place where participants are able to bring their expertise that they carry from all lived experiences, both personal and professional, into conversation with other distinct perspectives and ways of knowing.

The Stewardship Salon concept drew inspiration from a 2017 workshop called “Learning from Place” that brought Kekuhi Kealiikanakaoleohaililani, a Native Hawaiian kumu, and her learners from Hawaiʻi to exchange with NYC stewardship practitioners. Kekuhi encouraged the participants to organize their own community prior to the exchange, to prepare themselves to be in dialogue with different ways of knowing and Indigenous practices. From this exchange, the Stewardship Salon concept commenced in New York City. After having hosted Stewardship Salons for over seven years, the NYC planning team felt ready to share the approach and drafted the Stewardship Salon Guide so that others can create these co-learning spaces in their community.

After having the privilege of planning, attending, and evaluating the four 2024 salons hosted in NYC, I now have the opportunity to reflect both on my experience learning alongside other practitioners, scientists, and artists and the ties between our conversations together and my field as an ecologist. Let’s travel back in time together…

Monarch Migrations with Michele Brody

I gathered with an intimate group of 11 others to attend my first Stewardship Salon hosted at the Bronx River Arts Center by Urban Field Station Collaborative Artist Michele Brody. We gathered in the sunlit gallery space to begin with our opening prompt, which asked participants to share about a particular “weed” or emergent plant and what it means to you. I shared about mugwort, a plant that has established in the yard of my parents’ home, where the canopy of a beloved red oak once cast its shadow. Unbeknownst to me, mugwort ended up being a popular plant among the group for both positive and negative reasons, associations, and memories. And by the end of the salon, I reached a full circle moment when we were all invited to share a cup of mugwort tea— a drink which I might try to harvest leaves for, come next spring.

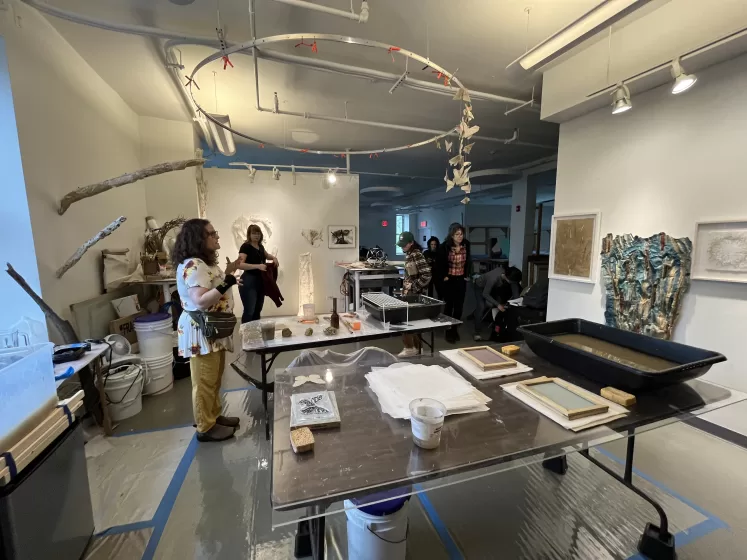

Through observing Michele’s work and practice during a tour of her studio space, I contemplated feelings of loss and change as I saw her works of casting “native plants” in paper made from those plants that have caused displacement. This led to an overall discussion on language, communication, and the impact of word choice. This intention initially could be seen with Michele’s project “Monarch Migrations”, which involves origami butterflies created from milkweed paper decorated with the migration stories of those who created the shape. Michele deliberately worded the prompt for recorded stories to focus on migration instead of immigration, because of its more flexible interpretation. Michele mentioned that she’s received stories on the butterflies ranging from high school students migrating to the US, to animal migration, and the migration of diseases around the globe.

I thought about my past work investigating seed dispersal in a tropical forest, which itself, is a form of migration or movement. I observed the important role people have in dispersing seeds directly as well as facilitating the movement of seeds by attracting animals to their land through the purposeful fruit tree planting. With climate change, forest conversion, and defaunation occurring in regions across the globe, there might be a growing need for human-facilitated movement of plant species. The USDA’s Northern Forest Climate Hub is currently spearheading some of this work on assisted migration of tree species at the boreal/temperate transition zone. This is not a new role for humans; we have always moved plants around both accidentally as well as purposely through trade and necessity. People have even helped to sustain several plants that were previously dispersed by now-extinct megafauna, like the ground sloth or native horses (ecological anachronisms), such as the avocado, papaya, and the pawpaw (see more in Guimarães et al. 2008). This connection just further cemented how spanning the concept of migration or movement is a necessity for most species to survive and persist by moving to a new environment, including humans.

The conversation of language expanded as attendees made connections as well to word choices in natural resource management, of how we communicate about “unwelcomed” migrating species. Often names and terminology in natural resources stem from a place of privilege which can lead to exclusive language. Participants provided many alternative examples to communicate with greater inclusivity when talking about: invasives (ex. short-term residents or pervasive species) or natives (ex. long-term residents) species or citizen science (ex. community or participatory science), as well as removing place names in invasive species naming because of its irrelevance to ID and association with people (see ESA’s Better Common Names Project).

I left the Stewardship Salon feeling invigorated from both the community and conversation, feeling empowered knowing that I took away a new language to express ideas around and communicate about invasive species and species migration, that I could immediately integrate into my practice as an ecologist.

Tracing Flushing Creek with Guardians of Flushing Bay

It was again in June, when I made the trip down to NYC, this time to Flushing Meadow Corona Park in Queens on what felt like the hottest and most humid day of the year thus far. Yet, the oppressive weather conditions didn’t deter the large group of over 30 attendees from gathering together in the early summer sun. This salon was led by Rebecca Pryor from Guardians of Flushing Bay, a local stewardship group focused on ecological restoration, environmental justice, and community engagement. Rebecca led participants on a “cultural daylighting” walking tour, tracing the path of Flushing Creek in Flushing Meadows Corona Park and discussing the waterbody’s history of transformation.

Gathered first in the air-conditioned reprieve of the Queens Museum and then outside underneath the shade of trees, we began with our opening prompt: describe a relationship you have with a stream, a creek, or another body of water. I described the river that I have fond memories of playing in the rocks both as a child and as an adult who enjoys looking for benthic macroinvertebrates, like dragonfly nymphs or water penny beetles. The relationships to waterbodies described by participants were vast both relationally and geographically.

We then shifted to focus on the waterbody we gathered for: Flushing Creek, the mostly underground stream we were going to be tracking. Like a detective, during our walk, we looked for signs of water. We looked for flood-prone areas, those where the grass is greener, or where we saw hydrophytic or “water-loving” plants like cattails (Typha spp.). Looking for these water-loving plants reminded me of first learning about indicator species, or those species whose presence or absence signals a particular environmental condition (such as saturated soils in the case of hydrophytic plants) or the health of the environment (ex. brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) need cold, clean water streams).

While walking we also talked about the concept of daylighting, a practice that was new to me, stemming from my naivety in understanding how we’ve built around and rerouted streams (including underground) to grow and develop our urban centers. Daylighting is the practice of bringing notice to buried underground streams. It can take many forms from resurfacing and restoring a stream channel to cultural daylighting which is acknowledging the water underground through signage, tours, art, and maps. We discussed the potential for daylighting Flushing Creek. For Flushing Creek, and like any daylighting project, it was stressed that it is necessary to understand current uses, values, and meanings of the space, through tools such as the New York Field Station’s social assessment method, and implications for drainage and flood risk.

As our time together was winding down, we ended with the Flushing Creek card deck, a deck created by artist Cody Hermann, which includes cards for the environmental/social components of the watershed and larger-scale factors (e.g., climate change). Each of us, with a card in hand, collectively told part of the creek’s imagined future. Without direction to do so, the group told a story of hope and successful collaboration to better care for a healthier watershed. I left with an optimistic feeling, gained from the group’s outlook on the future. I also walked away with a better understanding of the complexity of environmental project planning. Daylighting projects, conservation projects, restoration projects, and other environmental projects are guided by goals and vision outlined by “stakeholders”.

This Stewardship Salon reiterated to me the importance of inclusively involving community members from the beginning of a project including current site users, those who have visited the space in the past, and those who might face barriers to using the space present but would like to in the future—while not forgetting the non-human residents either.

Seeing Stories with Reimagine Lefferts House

After a two-month break during the summer field season, the Stewardship Salon community regrouped in September at Lefferts House in Prospect Park, Brooklyn. Led by Dylan Yeats and Riah Kinsey, from Prospect Park Alliance, we examined Reimagine Lefferts, an effort to “commemorate the past in order to build a better future” by providing an opportunity for “Lenape and African descendant communities to reclaim a colonial battlefield and site of enslavement to celebrate the resilience of their ancestors”.

We gathered outside, underneath the newly changing foliage of the park, to introduce ourselves to one another, place, and share an example of a person in your life that is meaningful to you (this could include ancestors, relatives, friends) and if there is a special place you go to connect to the memory of these people. I shared about my maternal grandfather who had a hand in shaping my relationship to the environment through hearing stories about and seeing first-hand the fruits of his gardening wisdom and love for working the land. From the opening go around, it was clear that many memories of loved ones have a strong connection to the act of preparing food (whether growing it, cooking it, or simply the aroma of a dish). Food, as a generational and cultural thread, is linked to the restorative and healing practice of creating biocultural foodscape or agroforests and to some of the goals Lefferts House has in installing a three sister’s garden and a native/medicinal herb garden in the coming years.

After the introduction to each other―the attendees of the Salon, we were introduced to the known, enslaved individuals who lived and worked at Lefferts. Our hosts took turns reading out the 25 names, taking pause after each name for us to repeat them back together, powerfully as one voice in unison.

We were then given time to independently explore the Lefferts House Museum and community space including the installation from Adama Delphine Fawundu’s site-specific work, Ancestral Whispers. The main installation includes 25 fabric banners which are displayed on the exterior of the house, “inspired by and honoring the heroism of the 25 Africans enslaved by the Lefferts family” (see Prospect Alliance’s Site for more information). Inside the house on a hallway wall, I was struck by a quote from Fawundu. It read:

Our bodies are archives. This house is an archive. This land is an archive. Everything is weighted with memory…

I was reminded of an ecological concept learned in school, the shifting baseline syndrome. This syndrome is a type of “generational amnesia”, forgetting, or shifting norms of what environmental conditions have been, and should be, due to degradation (see Soga and Gaston 2018). Yet, Fawundu’s quote highlights that memory is intertwined in the fibers of life and place. Ecological memories on the landscape can be seen through sediment cores, seed banks, relict species, and glacial erratics but also through memories carried in local and traditional ecological knowledge. Intentional storytelling for both human and non-human beings, like that being done at Lefferts, is an essential part of remembering that can contribute to healing. This shift of remembering also informs the memories from the present to be etched for the future.

Understanding Trail Accessibility with Natural Areas Conservancy

On a picturesque October day, I found myself in a large, forested area―a place I never expected to find in NYC. A group of 20 gathered at Greenbelt Nature Center within LaTourette Park in Staten Island to explore the trails and discuss both the physical and social dimensions of accessibility. Underneath the sunlight that flickered through the remaining tree canopy, we listened to each other’s answers to the opening prompt: what does “good access” feel like or mean to you?

I shared about physical access. Specifically, I thought about trails I have walked that were built for those with mobility needs. Those that might have a lower graded slope, be cleared of tree roots, or include wooden boardwalk features to cross small streams. I also reflected on creating trails that have spaces to experience nature “differently” or more sensorial (see Letchworth State Park (NY, USA) Autism Nature Trail). Others shared about access through the lens of public awareness (i.e., advertisement of the space), transportation, and feeling of the space to invoke comfort and invitation. After hearing from participants of their views of good access, we headed out on the trail to first experience some of the trail improvements from their Universal Access Project through a silent and slow embodied walk, to take in the sights, sounds, and topography of the trail.

Photo: Neha Savant.

We stopped around 300 ft into the trail at a small puncheon, a wooden walkway that extended over an area that seasonally floods, one of the universally accessible features that had been implemented only two years ago. To our surprise, the work done to those first 300 ft of trail to smooth the substrate for accessibility was not maintained, as rainstorms had washed gravel onto the trail making the path difficult for feet or wheelchair wheels to navigate. The group discussed how most trails were desire lines, or informal pathways, that then became formalized, not necessarily fitting the hydrology or the soils of the area. On top of that, as one participant explained, the situation for maintaining a stable surface on trails in Staten Island is especially challenging as the soil substrate is mostly glacial till, leading to perpetual loose rock/sand. Trail sustainability depends on whether construction has taken into consideration the hydrological and soil conditions of the site.

Suddenly, I was transported back to my stream ecology class to the lecture where we learned about the impacts of channelization on streams, or removing the sinuosity from “the moving conveyors of water a sediment”―the definition of a stream that was seared into my mind from that course. Channelization can cause water to move faster, increasing rates of erosion and turbidity levels, deepening the channel (through downcutting), and impacting the life found in the stream. In some ways, trails can act as channels, especially those trails that were created from desire lines which might follow the shortest distance to the destination instead of a pathway meandering with the topography of the landscape. I’ve witnessed many steep Adirondack Mountain trails turn into a channelized stream during a rainfall event, dangerously eroding away to soil and deepening the trail. There are many efforts to reconstruct trails to have them fit the hydrology, soil, and topography, for steep trails this can include adding in switchbacks, or trail sinuosity, which reduces the rate of erosion.

Trail construction is labor intensive in the years of planning a project and in the months of difficult physical labor, moving soil, rock, and wood to realize the project on the ground. However, trails do not stay functional without maintenance, as was evident with the walk (see NYC Strategic Trails Plan). Yet, maintenance simply does not receive the funding that new construction does, as many participants noted. The conversation provided insight and validation to my understanding that there simply isn’t enough funding for the many necessary stewardship and conservation projects. Continuing the walk on the trail, my mind thought back to Upstate NY and the thousands of miles of trails that exist. I reflected on the many trails I have tramped on that are quite eroded and degraded, turning into streams during a rainfall or snowmelt event. Although the majority are in great need of maintenance, I also remembered the trails that had unique features that contributed to my comfort. Some of these features included mile markers and signage that showed how far along the trail you were and the upcoming elevation changes, which contributed to a sense of safety as a woman hiker navigating remote areas (read more about people’s perception of fear/fascination in NYC’s natural areas in Falxa Sonti et al. 2020).

As we said our goodbyes, closing out the last Stewardship Salon of the year, I felt thankful for being in the company of others so passionate about stewardship and natural resources work. Individuals with different backgrounds, carrying different environments near and dear to their hearts, gathered together because of this universal care for our world. I walked away with the sense that there is so much work still to do but knowing that there is a network of individuals working together to steward our communities and environment.

My participation in the 2024 Stewardship Salons illuminated some of NYC’s expansive, biocultural mosaic and the plurality of stewardship relationships on the landscape. Just like the diversity of perspectives shared during the events, all attendees take different reflections, ideas, skills, and strategies learned with them to then incorporate into their personal or professional practice. I ponder the impact these spaces could have on my own small town and the region I’ve grown up in:

I think about the efforts along waterways throughout the Adirondacks to stop the spread of aquatic invasive species and how messaging to the community could be made more inclusive and less militaristic.

I think about a creek in my town―a tributary of the Sacandaga River eventually feeding into the Hudson, the legacy of pollution and industry, the life inside and outside of the stream that has relied on that water, and the possibilities to seek out the indicator species signaling the water health/impairment and to highlight its downstream flows, now flooded, to form the Great Sacandaga Lake Reservoir.

I think about the efforts underway to elevate the Indigenous and Black stories past and present of the region I call home. There are ongoing efforts to re-story the Adirondack region: to not only include the stories of logging, “exploration”, and retreat into the woods by the White, wealthy, but stories of resistance and flourishing (see articles found in Adirondack Life and the Adirondack Explorer). These efforts might launch the region into a more welcoming future that fosters a broader sense of belonging.

Lastly, I think about the accessibility of the Adirondack region. Despite the proximity some of these places have to towns and cities, many of these areas may not see local visitors due to lack of public transportation. Conversations are needed to explore how we better connect people to their surrounding landscapes.

I invite you to ponder the impact of these spaces and themes as well, with our Stewardship Salon Guide providing some support in imagining what they could look like in your community and place.

about the writer

Julie Hernandez

Julie Hernandez is a European-descended settler who grew up and still resides in the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York. She classifies herself as a community ecologist with an interest in the biocultural restoration, conservation, and the relationships between plants, food crops, animals, cultures, languages, and place. Currently, she works remotely as a Program Support Specialist intern with the USDA Forest Service’s NY Field Station (based in NYC) through the Resource Assistance Program (RAP). Julie holds a bachelor's degree in Ecological Restoration from Paul Smith's College and a master’s degree in Conservation Biology from SUNY ESF.

Julie Hernandez

Amsterdam, New York

Add a Comment

Join our conversation