At the international conference Resilience 2008, which gathered more than 600 leading scientists, business leaders and politicians in Stockholm, Sweden, I was struck by the Changing Matters art exhibit that explored resilience themes. One of the artists, Jon Brunberg, shared a piece called 19 Years, a one-minute Flash animation that depicts the more than 91 million people around the world who took part in mass demonstrations between 1989 and 2007, crying out for change. Locational dots appear on a screen showing a world map, gradually at first, but increasing in intensity, accompanied by the jolting sounds of fire-crackers popping, each corresponding with the appearance of a new dot, a new mass demonstration. The dots and sounds crescendo to an alarming level as time passes, communicating the urgency and power of humanity’s will and alluding to their capacity to change things, to shake their realities into new ones. Experiencing this art is a sublime experience, paradoxical in its inspiring yet disturbing spectacle. One is moved, somewhat overwhelmed, alarmed and yet optimistic.

Similarly, in urban post-disaster and post-conflict situations, I have seen equally overwhelming, alarming, and yet optimistic human responses, demonstrating the extraordinary resilience of our species. Some of the most intriguing and inspirational responses to disaster and conflict are found in the mysterious realms of altruism. One needs only to recall the week of September 11th, 2001, in New York City and Washington D.C. to conjure images of selfless heroes and an understanding of this type of response.

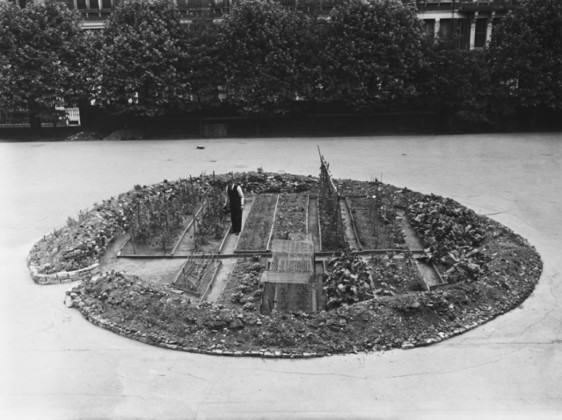

Another form of response is somewhat more muted, but in the end, perhaps equally, or even more profound. I am referring to the response by both individual and groups of humans to return to “nature” when calamity strikes, to actively seek intimacy with other living things, to retreat (or advance!) to life-affirming interactions in verdant, alive contexts. Often these responses start with individuals and grow into movements larger social movements and even government sponsored programs. I am highlighting how brave people combine their own fate with that of the animal, tree, flower, forest or garden that lives or dies. This type of response, the many motives and explanations for how it comes about, and the implications of its presence and efficacy in terms of resilience and sustainability is an area of inquiry that I call “greening in the red zone” and is the name and subject of a forthcoming book.

At the time of this writing, the conclusion of the first decade of the 21st century is “in the rearview mirror,” and as we advance into the second decade the world is still reeling from what seems to many to be increasingly frequent perturbances. Recent multiple earthquakes and disasters (Japan, Haiti, Chile, China, and others) have punctuated an already chaotic ten-year period that has seen buildings felled by terrorists from New York City to Nairobi, wars in the Middle East, catastrophic flooding in New Orleans, mudslides, typhoons, complex disasters such as in Fukushima Japan, and the list goes on. But as troubling as these events are, they are not in themselves particularly new phenomena. Even in my own lifetime, I have noticed the predictable likelihood that disasters will happen.

My early upbringing was as the child of a minister in the prairie country of Minnesota, in the north central USA. We were not strangers to natural disasters; every summer communities near us, and sometimes our own community, experienced the devastating power of tornadoes. I grew up with ‘70’s era TV images of families weeping while standing where their trailer used to be, or where their barn used to be, or even standing where they last saw members of their family. These were terrifying images, but they were also fascinating. I was at an early age captivated by the human survival instinct in the wake of calamity, and motivated to gain an experiential understanding of these human traits.

Being a minister’s child, I was exposed to different cultures around the world through missionaries. When our family moved to Detroit, these impression-making interactions increased. In the summer of 1988, between my junior and senior year of high school, I experienced my first international disaster. I travelled to Haiti to work with Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF), a faith-based, nonprofit organization founded by military pilots to use aircraft to help missionaries respond to disasters. MAF currently operates 136 light aircraft to support their outreach and humanitarian relief and development activities in 38 nations, providing aviation support in a variety of settings. We were assisting a community near the city of Cap-Haïtien, which had experienced damage to hillside buildings, including a school, during Hurricane Emily in 1987. It was here that I began to understand the links between people, the rest of nature, and the outcomes of surprise events like so-called natural disasters or other catastrophes.

According to Jane Deren of Education for Justice, during the 1980’s, Haiti still had 25% of its forests, which allowed the tropical island nation to endure rain events like 1987’s Category 3 Hurricane Emily, with minimal loss of life. But, she says, as of 2004, only 1.4% of Haiti’s forests remained. The effects of this slow erosion of a source of Haitian social-ecological system resilience are now being felt. Storms Jeanne and Gordon were not even officially hurricanes when they descended upon Haiti, but the almost complete lack of tree cover has been pointed to as a major contributing factor to the devastating floods that killed thousands. And, according to some, it doesn’t even take a tropical storm to seriously disrupt the Haitian system — in May of 2004, three days of heavy rains from a tropical disturbance dumped more than 18 inches of rain in the mountains, triggering floods that killed over 2600 people. Tragically, the tens of thousands of Haitians who died as a result of the 2010 earthquake are further testimony to the loss of resilience within the Haitian social-ecological system. (For an exhaustive body of work on Haiti and forestry, see anthropologist Gerald F. Murray’s research portfolio.)

My own experience in disaster relief in Haiti over 20 years ago was extraordinary in many ways, but one experience stands out in particular. There was a small school perched precariously on a slope. The school had been closed since the storm of a year earlier, as it was deemed unsafe. Portions of the exterior showed signs of slumping down the hill. Every day, women and older men were planting small trees on the uphill side of the building. I asked someone one day what they were doing, and the person replied, in a rather condescending way, that they were wasting their time trying to save the school. About a week later, I heard a man yelling and whistling shrilly. I looked in the direction of the noise and saw the tree planters scurrying away from the school. Moments later, the building totally collapsed and slid a little ways down the hill. The entire community seemed to assemble at the site within minutes, and there could be heard great cries and wailing, yet thankfully, no one was injured. After about an hour of this, the women who were planting trees, and two or three of the old men trudged up the slope and resumed their planting. Slowly, others climbed to assist, until there were maybe 30 people on the side of the hill above the rubble. I was greatly moved.

Later, I mustered the courage to ask our host to help me pose some questions to the tree planters. I asked them why they continued to plant trees when the school was destroyed. The interpreter asked my question in Creole, and there were many answers, and much hand waving. I thought I had offended the people. Then, the interpreter turned to me with tears in his eyes. He said:

“We didn’t plant the trees to save the school. We planted the trees to save the children in the school. We are still planting the trees because we are still worried about our children. We are planting the trees because there is nothing else we can do. See? We are not crying here, we are planting trees.”

More recently, on 29 August 2005, New Orleans endured weeks of inundation and devastation, and months of disorganized recovery efforts as a result of Hurricane Katrina. Yet despite media reports portraying New Orleans as paralyzed and helpless, or even worse, descending into chaos, ordinary citizens were observed planting and caring for trees in neighborhoods across the city. Within four years after the disaster, three local NGOs, Parkway Partners, Hike for KaTREEna, and Replanting New Orleans, worked with community volunteers and government agencies to plant over 6000 trees in hard hit areas. Interviews I conducted with volunteers in the devastated 9th Ward and other New Orleans neighborhoods, and with leaders of local NGOs, revealed how trees and replanting trees were critical in bolstering people’s resolve to rebuild their lives, and how memories of the live oaks and other trees that had been symbolic of New Orleans as a place to live became a symbol of hope for re-growth of the city and of their lives (see Tidball, K. G. 2012, Greening in the Red Zone: Valuing Community-Based Ecological Restoration in Human Vulnerability Contexts. Department of Natural Resources. Ithaca, NY, Cornell University: 355; and Tidball, K. G. 2012, Trees and Rebirth: Symbol, Ritual, and Resilience in Post-Katrina New Orleans. In Greening in the Red Zone: Disaster, Resilience, and Community Greening. K. G. Tidball and M. Krasny. New York, Springer-Verlag.)

It is my hope that greening efforts that I have witnessed first-hand, like NYC’s Million Trees program, New Orleans’s post-Katrina greening efforts, the Greening of Detroit, and the ReLeaf Joplin movement can become inspirational to policy makers and planners in post-conflict and post-disaster contexts, especially in large population centers, and also affirming and inspiring to community greeners everywhere. I am optimistic that humanity can recall its collective connections to the rest of the biosphere, especially in times of crisis, and that such recollection will help us remember our way out of current pathologies and learn our way in to a sustainable urban future on ever-changing planet earth.

To learn more about Greening in the Red Zone, see: http://www.springer.com/environment/environmental+management/book/978-90-481-9946-4 and http://greeningintheredzone.blogspot.com/

Keith Tidball

Ithaca, NY USA

Leave a Reply