Jane Jacobs titled her sixth book The Nature of Economies (Random House, 2000). In the Foreword she makes explicit her intent:

“The theme running through this exposition — indeed, the basic premise on which the book is constructed — is that human beings exist wholly within nature as a legitimate part of natural order in every respect. To accept this unity seems to be difficult for ecologists, who assume –– as many do, in understandable anger and despair — that the human species is an interloper in the natural order of things. Neither is this unity easily accepted by economists, industrialists, politicians, and others who assume — as many do, taking understandable pride in human achievements — that reason, knowledge, and determination make it possible for human beings to circumvent and outdo the natural order”. Foreword, The Nature of Economies, Jane Jacobs

Jacobs then proceeds to describe how economic development follows a set of patterns that mimic the patterns of a natural ecology: differentiations emerging from generalities, which in turn produce more differentiations, and the process of co-development. The Nature of Economies followed on the heels of Jacobs’ previous books — beginning with the ever-classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), through two other economics volumes: The Economy of Cities (1969) and Cities and the Wealth of Nations (1985).

Although her first book (Death and Life…) seems to be the better known in the US, these subsequent ones lay out in provocative detail a way of seeing cities and their economies — and the people who inhabit and participate in them — as a totally integrated part of nature. Her book plays with this double meaning — describing for us the character (nature) of economies while at the same time binding human settlements to nature. I have understood the intent of The Nature of Cities blog to be the same: to provide narratives of how nature resides in the city, but also as a lens into our understanding the composition of the city as natural.

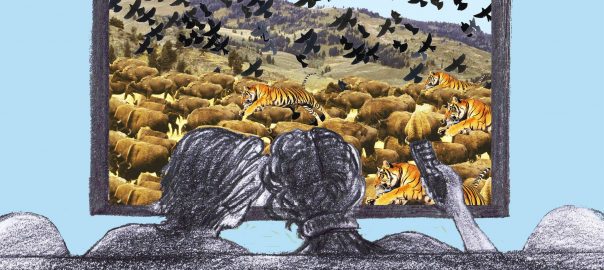

However, the demonization of cities, juxtaposed as it has been against an idealized rural or pastoral landscape, is such a hard meme to break, so often reinforced through popular culture. Television, movies, and literature generally depict the city as the embodiment of crime, trouble, evil, while promoting a sentimental and nostalgic view of small town or rural life. This, then, gets concretized in policy discussions at every level. Density is feared: leading to crime! Over crowding! Higher incidences of HIV transmission! Homelessness! I participated in a meeting last week in Geneva, hosted by several UN agencies and attended by civil society organizations drawn from the global north and south. As part of a larger preparation to review progress towards achieving the UN Millennium Development Goals (which expire in 2015), I found myself in lonely company advocating for the benefits of cities and the promise of urbanization to improve societal outcomes.

How entrenched our belief systems are: that cities need to by fixed, altered, rescued. (Even UN Habitat’s current campaign to link practitioners around the world doing innovative city building, of which MAS, my employer, is an international partner, chose “I am City Changer” reinforcing the notion that cities need changing …).

Once you start watching for it you spot a latent misanthropy in almost every domain. The community development work in North America and Europe over the last six decades has only reinforced this, rallying efforts to “re- store/mediate/vitalize cities”.

To what? Their more ‘natural’ state?

Fortunately, the life sciences have indeed come to our rescue, over time out-jockeying the mechanistic, linear-ists, persuading us in many aspects of living to look at what is generative, organic, connected to the whole. Jane Jacobs observed city life as inter-connected with the natural and built environments, and her ideas have prompted a contemporary approach to urbanism that integrates uses and users, green architecture and design, local economies (even currencies!), adaptive reuses, and ecological infrastructures. These reflect Jacobs’ recognition that cities — when permitted to — evolve naturally, adding form and function as needed. Jacobs’ method was a simple scientific one: to observe the particular, and extract from it her observations about how cities actually work. She was allergic to ideology, knowing that the complexity of relationships and occurrences in cities most often would produce surprising results that no abstract theory (or its adherents) could predict (or control).

Cities are full of exception, occurrences of serendipity and delight, of innovation and thrift, where someone has tinkered or improvised or been resourceful or imaginative. Good public policy and programs enable the city to make this possible for people. But well intentioned (and some not so) policies inhibit this natural process of city development. Jacobs was notorious in her calling out of large-scale efforts to ‘improve’ the city, seeing them as arbitrary mechanisms to ‘control’ — when in fact what she saw was needed was support for the natural processes that were always occurring in cities, but too often stifled by a number of public and private forces.

Self-organization: the livability of the city

Jacobs observed in the city people’s desire, and capacity if enabled, to self-organize: a concept with which ecologists and technologists are most familiar.

[For an elegantly clear synopsis of Jacob’s ideas on self-organization and how they connect to other natural and manufactured manifestations of it, please read Stephen Johnson’s Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software (New York: Scribner, 2001).]

As suggested above, the capacity for self-organization is a critical attribute of city life. If it’s compromised, so is the healthy functioning of the city. Self-organization occurs at every level of city life: within households, city blocks, neighborhoods, districts, the city and region. Walking groups, street vendors, business improvement groups, neighborhood watch initiatives, buying clubs, co-locations for the self-employed, street fairs, affinity groups of all kinds: the desire for city dwellers to make connections with others is what ensures a city is productive and vital: livable. Cities are not an artificial construct (at least the most successful ones aren’t). They are creatures of the living: created by people seeking to organize their lives in ways that sustain and nurture. The dynamism that self-organization delivers, is what we call livability.

As suggested above, the capacity for self-organization is a critical attribute of city life. If it’s compromised, so is the healthy functioning of the city. Self-organization occurs at every level of city life: within households, city blocks, neighborhoods, districts, the city and region. Walking groups, street vendors, business improvement groups, neighborhood watch initiatives, buying clubs, co-locations for the self-employed, street fairs, affinity groups of all kinds: the desire for city dwellers to make connections with others is what ensures a city is productive and vital: livable. Cities are not an artificial construct (at least the most successful ones aren’t). They are creatures of the living: created by people seeking to organize their lives in ways that sustain and nurture. The dynamism that self-organization delivers, is what we call livability.

Cities in fact are a living unit themselves, ebbing and flowing with the increasingly global tides of commerce and politics, ingenuity and will. Bees make their own hives and ants their own hills, created as part of the larger ecosystems in which they thrive. Surely cities are Homo sapiens’ greatest creation, similarly embedded in a larger web of connection to the assets and resources that surround them.

Systems of connection: an urban ecology

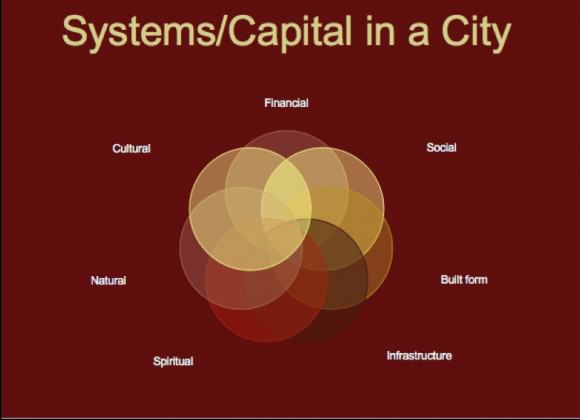

The webs of connection in a city are ‘hard’ and ‘soft’. They enable flows, of people, material, energy, waste. Some formalize, some remain ad-hoc. Every city has these, some are more challenged than others in making these channels of connection work effectively, These systems of capital are what fuel the city. In turn they interweave, or ‘nest’, forming an urban ecology.

[For a full and lively description of the vitality of cities, please see Roberta Brandes Gratz’s The Living City: How America’s Cities Are Being Revitalized by Thinking Small in a Big Way, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1994). Gratz is also the co-founder with Stephen Goldsmith of the Center for the Living City, an organization founded on the principles of Jane Jacobs.]

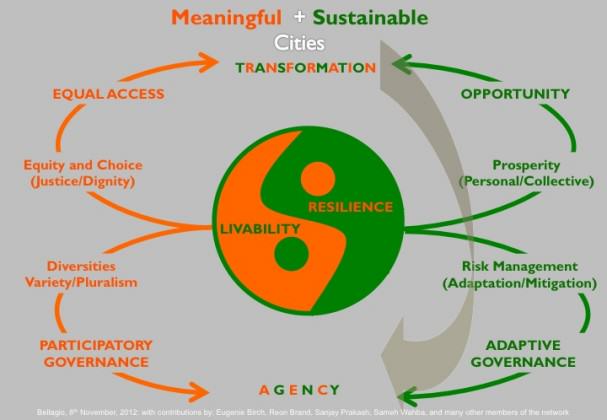

Increasingly in the imaginative, innovative pockets of city-building there is a recognition that small, seemingly modest local initiatives aggregate up into a whole that makes a city not only more livable, but are also critical contributors to a city’s resilience. These are the two sides of the self-organization coin: a city’s capacity to meet the needs and aspirations of its dwellers (livability) and to productively adapt to diverse challenges and opportunities over time (resilient).

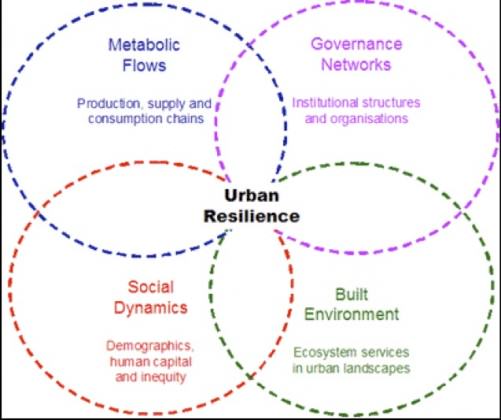

A resilient city has the capacity to swiftly adapt to change and capitalize on opportunity. Although more recently associated principally with climate change adaptation, resilience is a term with resonance across multiple domains (e.g. psychology, biology, engineering sciences, business continuity, community development). Inherent to urban resilience is an integrated, holistic understanding of the connectivity and interdependence of the physical, social, environmental and cultural assets and systems of a city.

The Stockholm-based Resilience Alliance has created this graphic (an instrumental version of my ‘systems of capital’ above) to illustrate these interconnections.

Any city needs resilience-building strategies that protect it — its neighborhoods, housing, institutions, commercial life, open spaces, cultural assets, and its systems that provide food, transport, health, and protection — from the widest range of risks and challenges.

System-wide investments are crucial, but they need to be underpinned by granular strategies that enable self-organization: where neighborhoods, sectors, institutions are empowered by city dwellers who foster resilience in their homes, workplaces, and places of worship, learning and leisure. Resilience is not a household word (yet), remaining for most an abstract concept confined to engineering schools, scientists, and psychologists.

On the other hand, the concept of urban livability — what a city provides its dwellers to make their lives safe, healthy and meaningful — is a term that resonates with most. Marrying the concepts may be a ‘no-brainer’ to some of us, but certainly decisions that dramatically affect our city life are still most often taken in isolation: public housing is sited where land is cheap but services are costly to deliver (and therefore inadequately delivered); zoning changes incentivize profitable development but crowds out the legion of smaller enterprises that make a neighborhood vital and diverse; public investments in open space, parks, and libraries are cut back, denying the multiple social, economic/environmental benefits these community amenities can potentially deliver to their neighborhoods and the city as a whole.

It may be now that a ‘resilience imperative’, ushered in by more recent severe weather events, will make more urgent the need for public and private investments that boost local resilience, and simultaneously, one would hope, livability.

A livable and resilient city

My city, New York, is arguably one of the world’s most livable ‘global cities’ — absorbing continuous population growth and providing opportunities for immigrants, an international center of knowledge and wealth creation and innovation, a cultural mecca of diversity provided formally through a wide array of institutions and informally on every corner, and with a mix of amenities and attributes that makes for many New Yorkers a daily routine that is productive and enjoyable.

But there are persistent challenges that inhibit this city: areas of concentrated poverty, limited housing choices, land use development pressures that threaten the existing vibrancy of their neighborhoods, and the chronic need for more investment in infrastructures of all kinds, made all the more prescient by the storm events from which we continue to recover. These challenges are common to cities of the size and intensity of New York. The plethora of livability indexes popularized through niche media (Monocle) or global accountancy firms (Mercer) and routinely rank ‘global’ cities like New York, London, Hong Kong and Mumbai very low down the list, providing little guidance or useful measures for improvement for cities as vast and complex as the world’s largest and most productive.

In fact, on-the-ground practitioners connect every day with the physical city: entrepreneurs, activists, designers and planners, artists- and know that city-building is not a zero-sum game. And civil society movements — originating in cities — make clear these win-win opportunities: ‘creative place-making’, ‘localism’, ‘shared streets’, ‘universal design’ are each about mobilizing local assets to generate livability and resilience benefits.

Our largest and most intense cities, whether in the northern or southern hemisphere, are facing increasing challenges placed on them by growing populations, resource demands, aging infrastructures, resource scarcity, and economic downturns or uncertainty. They are also home to remarkable social innovators, designers, entrepreneurs and artists, energized by city life and constantly improvising ways to make life in the city meaningful, just, and productive. These new approaches are most often hyper-local, starting modestly but generating results that could easily be scaled up to have greater impact.

We have much to learn about effective approaches to building city resilience and livability. Whereas New Yorkers may envy the spectacular adaptive reuse examples of London, Hong Kong looks to us for lessons in integrating historic preservation into its land use and economic development strategies. Similarly, what do the informal economies and public markets of Mumbai have to teach other city building practitioners about how cities can foster an entrepreneurial ecosystem? And what about the network of social innovation entrepreneurs tackling urban design challenges in Bandung and Rio?

Beginning in 2011 the organization for which I work, the Municipal Art Society of New York (MAS) — a century-old advocacy organization concerned with the relationship between the city’s built form assets and its people — began reaching out to urban innovators: artists, designers, planners, teachers, and entrepreneurs living in other global cities to share approaches, and discuss disruptive innovations that are making their cities more livable and resilient. This initiative is based on a theory of change that urban innovation is fostered locally and then scaled up, and continuously adapted to changing conditions, with the support of enabling public policy and investment.

Our most effective instruments of livability and resilience scale in both directions: for instance, community gardens and naturalized spaces could hold storm water, grow and distribute food, show art, mitigate urban heat island effect, host Tai Chi and/or a FEMA trailer, dispense flu shots, provide local respite places, show movies, offer wi-fi hot spots or charging stations, display locally created maps or evacuation instructions from the City, provide a pop up space for the branch library These approaches contribute to the livability and resilience of the city.

Connecting cities with cities: growing the urban ecology

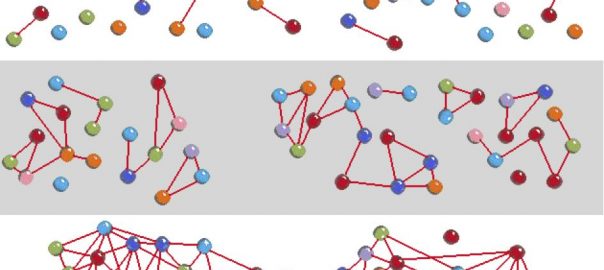

The world’s global cities make possible the peer-to-peer trading that fuels the global economy, which is fundamentally urban, facilitating connection between entrepreneurs, researchers, investors and consumers. Nowhere is social media more robust than in the global cities of the world, and speaks to the appetite of urbanists to learn from each other. Aggregating those examples necessitates creating platforms to connect and nurture the global urban resilience ecosystem of practitioners.

Similarly, a network creates a platform for the exchange of practices to improve the livability and resilience outcomes of their cities, and in the aggregate, over half of the world’s population who live in the global city. It provides a unique learning and advocacy platform for the best in city-building practice, across sectors and disciplines, to spread the social innovations that potentially affect hundreds of millions of lives, and the natural ecosystems that support them. The value proposition of this initiative is that it is grounded in the practical: with an explicit commitment to link, across sectors and disciplines, with practitioners actively contributing to outcomes at the most local level.

An initial meeting of this Global Network was convened by the Municipal Art Society of New York and supported by the Rockefeller Foundation, with founding participants who are engaged in resilience and livability initiatives from two dozen cities around the world. The common finding from this group was the need to develop a ‘new paradigm’ that embraced the physical and aspirational nature of cities — see the draft paradigm below — and was relevant to cities in both the northern and southern hemispheres. What has emerged is a pattern of understanding the city as a living system, providing its citizens with opportunities and access, prosperity and dignity, protection and choice, and systems of engagement and governance that maximize livability and resilience. With a common framework, this initiative is now cross-pollinating innovations between city builders, strengthening the connective tissue within cities and between them.

Our next step is to create a digital learning platform, where we can, as Jacobsean urbanists, observe in our own cities and others, how livability and resilience are being ‘home grown’ and connected up, to strengthen the ecosystem in which the nature of cities, of the world, resides.

Mary Rowe

New York City

Leave a Reply