Small-scale urban spaces can be rich in biodiversity, contribute important ecological benefits for human mental and physical health (McPhearson et al., 2013), and overall help to create more livable cities. Micro_urban spaces are the sandwich spaces between buildings, rooftops, walls, curbs, sidewalk cracks, and other small-scale urban spaces that exist in the fissures between linear infrastructure (e.g. roads, bridges, tunnels, rail lines) and our three dimensional gridded cities.

But most of these micro_urban spaces are overlooked, unrecognized, and even invisible parts of our urban lives. Perhaps our inattention to these spaces is because they so often exist in between our more highly valued built spaces such as large parks, plazas, waterfront promenades, urban forests, rivers and much loved neighborhoods. One of the great biodiversity challenges for urban ecosystems is to solve the problem of high levels of habitat fragmentation in cities.

What if the micro_urban were the missing piece to solving the connectivity puzzle in our fragmented urban ecologies?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qk54Eun0SSU

These elements and experiences remain underutilized in ecological urban design practice yet are a ubiquitous feature of our urban infrastructure. Even low-level investment in these micro-spaces could provide new grounds for ecosystems to establish, for urban dwellers to socialize, and contribute to both well-being and community resilience to the many dynamic changes affecting social-ecological attributes of our urban lives.

A networked urban ecology

One of the critical biodiversity challenges in cities is dealing high levels of habitat fragmentation. Creating corridors between fragmented green patches in highly heterogeneous landscapes is difficult in older cities with dense built and technological infrastructure. And yet cities have immense potential for linking urban parks, wild spaces, and small green patches through green roofs, green roadways, and other corridor infrastructure that could provide species greater ability to move and migrate while increasing more equitable spread of ecological space throughout cities.

Micro_urban takes this idea further. Rather than a corridor approach that links already existing big green fragments we have been talking about how micro-spaces in any neighborhood with or without parks and with or without corridors could be networked or clustered to provide a networked ecology in cities. By seeing green roofs, green walls, sandwich spaces between buildings, and durational spaces together we have begun to imagine how people in cities could beginning greening well beyond new parks or retrofitted railways. How might micro_urban habitats that are networked throughout the city; up, over, around, and through our built and social infrastructure then make a difference in the social and ecological well-being of a city?

Walking

Recently, at the invitation of Mary Miss, we developed a guided walk for the City as Living Lab (CaLL) project. We took participants on a tour through the Garment District in New York and we asked them to recognize the potential for these micro_urban spaces to make a difference in the lives of both human and non-human species. We then went to the roof of the Port Authority Bus Terminal parking lot and through a simple drawing exercise we let each participant’s own desires and goals drive their own ideas of the micro_urban.

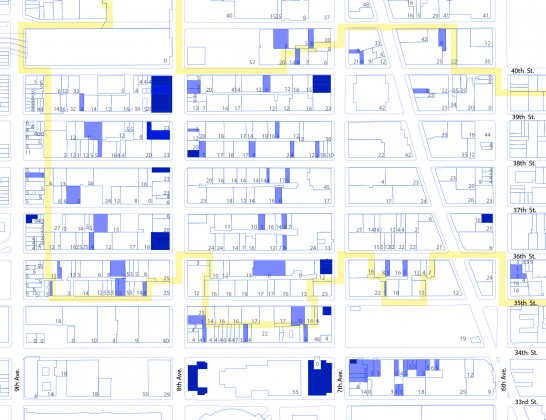

We took our inspiration for both the location in the Garment District and a way to focus our ideas on micro_urban from ongoing micro_urban research on Fourteenth Street in lower Manhattan (see references at the end of this essay) and from a visiting Parsons School for Design student, Yanisa Chumpolphaisal, a 2013 Graduate from Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok and a visiting student in the Parsons BS Urban Design program. She created a project titled “The Art of Capital” where she mapped the billboard corners, sandwich spaces, and the landscape of setback roof spaces in the Garment District.

This map served as the launching point for the CaLL Walk we developed. As you can see from Yanisa’s drawings, once you start to look for these small overlooked, underutilized spaces you find that they are evenly scattered throughout the city, by accident, by design, and by history; nearly everywhere in this area.

Yanisa’s familiarity with soi (small alleys in Bangkok) helped her imagine this area with new eyes Her images reveal how she started imagining what could be done with these spaces. How they could have positive impacts on the lives of local residents if they were reimagined as ecological and social space, and be an opportunity for improving the Garment District as a support system for artists.

Yanisa expanded on the way urban residents in Thailand and New York take advantage of every opportunity for socializing, and for small business. From this she drew possibilities between the social life and micro-spaces in the Garment District in New York. Right now those billboard corners, sandwich spaces, and setbacks are virtually bare of anything living.

Indeed, the more you look you begin to realize that the unmet potential is vast.

One of the main thrusts of urban ecological research and practice is to understand how ecological spaces can be co-designed, managed, and engaged in ways that improve the lives of both human and non-human species. These micro-spaces are opportunities and the locus for focusing the imagination of the artists, designers, and scientists who joined us on our CaLL walk.

On October 25th 2014 we gathered a group of urban ecology enthusiasts on the corner of Broadway and 39th Street in New York City and walked up to and along West 40th street toward the Port Authority Bus Terminal, observing the sheer number and possibility of the micro_urban.

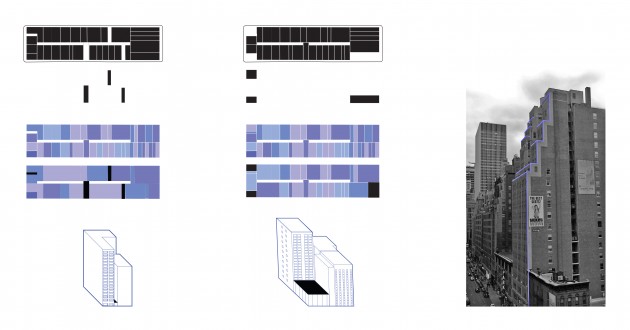

We motivated our group in two ways. First, we focused on three urban forms: the sandwich, the billboard corner and the setback. Second, we observed social-ecological interactions and spaces to imagine a networked ecology of the micro_urban.

In our walk, we first, observe these spaces, and second imagined the opportunities that exist over the space of just a couple blocks.

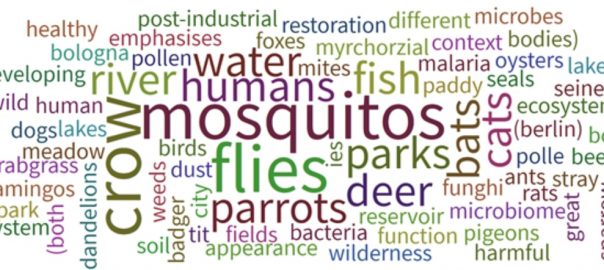

Ecologically, the fundamental idea is that soil, microbes, plants, invertebrates, birds, and other urban adapted organisms can exist in spaces we don’t traditional consider as ecological habitat. What if building owners, their tenants, the business improvement district and other urban actors intentionally managed these spaces to foster more diverse and healthy ecosystems? How might active engagement with the micro_urban help solve the connectivity puzzle in our fragmented urban ecologies?

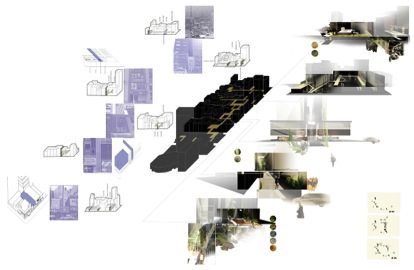

Drawing

Eventually we took our walk to the roof of the Port Authority, seven stories up, where we conducted a drawing exercise to allow each person to reimagine how these spaces could be used to change the Garment District. Everyone was given simple tools and a method of tracing (acetate on clear plexiglass and markers, developed by Jose DeJesus). We asked participants to use their imagination to draw how these three kinds of spaces, the sandwich, the billboard corner and the setback, might become more biodiverse. In simple terms, we asked them to look out, and look up, and to draw soil as a starting point for urban ecological change.

Our own goal in this project was very simple: to convey an understanding of the unique urban form of the area, to explore the potential of unused surfaces to become biodiverse.

We were also interested in the value and sociability of those spaces as ‘borrowed and collective views’ rather than gardens directly inhabited by humans. This more complex level—inclusive of insect diversity, microbe diversity, pollinator diversity—engages how these diversities might also begin to create new social spaces in a neighborhood undergoing rapid and dynamic change. It is at this point that were able to introduce the idea of people as part of green infrastructure—as a support system for biodiversity.

Our group was already highly engaged in thinking about important ecological problems in micro_urban spaces. For example: Could mirrors be employed to move sunlight into otherwise dark spaces? How might vegetation be encourage on vertical surfaces through creative use of novel growing substrates? Why is there moss here? How can water move differently on those surfaces? Who might build this? How might they work together? And so on.

Everyone chose a different scene to draw—some went to the far end of the roof, some drew the roof, and many drew the area we had just walked. Then we asked people to share what they had drawn. As members of the Walk presented their ideas at the end of the hour we were struck by how many different ideas there were, the sheer diversity and creativity, and overall how much is truly possible once you start seeing social-ecological opportunity in the micro_urban.

The metacity and the micro_urban

Often roof gardens are designed in a very high-tech way with many pleasurable amenities for people that increase the value of a property, such as chairs, colorful flowering plants and grasses, kitchen gardens, dining areas, and even swimming pools. We offered our CaLL walkers a more simple approach. What if it is OK that people can’t go on the roof? What if only soil was added, after which plants, insects, birds and other species colonized these spaces naturally. They may already be there—seeds move with the wind, and with birds that are flying around searching for places to perch.

McGrath and Pickett (2013) describe a nested mosaic framework as a metacity approach to modeling cities. They engage the term meta not as bigness but as a spatially extensive ‘system of systems’. Through the walk, the drawing exercise, the discussion, and our reflection on this experience we found that a soil-based imagination to this high density neighborhood afforded a metacity spatial understanding for action that could increase biodiversity, create a shared sociability for deeper engagement with natural processes in our cities, and greater well being through neighborly interaction above, and in addition to, crowded and contested sidewalks.

Our earthy micro_urban approach to the garment district was informed by the urban heterogeneity of this Manhattan neighborhood. It was also informed by walking as a base for engaging people as part of green infrastructure. There are other types of movement. For example, consider the difference in the sociability of the stroll, promenade, ramble, commute, parade, ceremony, game, festival, or protest. Each is a type of social space where action in relation to and with ecological spaces might be engaged with intention.

What micro_urban approach does your neighborhood afford?

Timon McPhearson and Victoria Marshall

New York and Newark

***

Selected References:

On Micro_urban:

Victoria Marshall, “Self-Centered Ecosystem Services,” Scapegoat, Issue 01 (2012).

On Metacity:

[second_bio]about the writer

Victoria Marshall

Victoria Marshall’s design practice is called Till Design. She is a registered landscape architect and is trained in both landscape architecture and urban design. Marshall is currently a President’s Graduate Fellow at the National University of Singapore where she is pursuing a PhD in the Department of Geography.

Leave a Reply