The drought in California over the last few years has been long enough and sufficiently severe to compel mandatory urban water restrictions from the State Water Resources Control Board, an unprecedented policy move. The Board has also required, for the first time in state history, the reporting of per capita monthly water use data. And yet, in Los Angeles County, which has 10 million people and 88 cities, impacts of the State Board’s water use reduction mandates (from a high of 35 percent to the average of 25 percent) have been very uneven. Poorer cities use less water per capita to begin with, and 35 percent reduction for some of the highest water users still allows them to use more than their fair share.

The fundamental factor driving outdoor water use is the currently limited vocabulary of urban landscaping and its potential future.

This drought-driven push for reduced water use has led to some savings, but years of replacing inefficient appliances—including toilets, shower heads and washing machines—with water-thrifty models means the frontier for water conservation in Southern California is outdoor irrigation. Landscape watering is estimated at 60 percent of total residential use. In an effort to curb outdoor watering, the regional Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, or MWD, provided $350 million to homeowners and businesses for turf replacement, and many cities, including the City of Los Angeles, have also developed their own complementary incentive programs for turf replacement. One could say without exaggeration that the MWD turf replacement incentive program is one of the largest natural experiments in landscape change ever undertaken. Websites replete with ‘California friendly’ landscaping tips and plant recommendations can be found from the state level to regional water agencies, including the MWD’s.

But to reach conservation goals, the more fundamental factor driving outdoor water use is the current vocabulary of urban landscaping and its potential future.

Californians are colonists, immigrants who brought their own vocabularies of landscape with them, or who had none and went for the easy and available. The dominant gardening vocabulary imported to California was based on an eastern U.S. aesthetic, where the lawn is the King of the Block in virtually all instances, bordered by exotic, often flowering, plants. As a result, in Southern California, British influence is stronger than Spanish: the Brits, with their passion for gardening, imported plants from all over their empire to create the decorative elements framed by The Lawn. They created a horticultural trade based in their colonies, so we have a rich selection of Australian and South African plants, but not as many from Italy, France or the rest of the Mediterranean. In fact, the official tree of Los Angeles (coral tree, Erythrina caffra) and the official flower (bird of paradise, Strelitzia reginae) are both from southern Africa.

Without an identifiable gardening heritage, Southern California’s benign climate and water—made available by the Los Angeles Aqueduct and Colorado River aqueduct—enabled an urban landscape that is a distinctive hodgepodge of imported plants. People planted whatever they could get their hands on, without reference to the region. Birds of paradise and banana trees sit cheek by jowl with camellias and azaleas, hedged by boxwood and fronted by lawn. One-hundred-foot tall semitropical ficus trees adorn parks planted with Cedars of Lebanon and Chinese elms.

At the turn of the 20th century, when the Craftsman style was being developed and many of the region’s iconic gardens, including the gardens at the Huntington Botanical Gardens, Descanso Gardens and even the Los Angeles Arboretum, were establishing, the design community pioneered a garden aesthetic for Southern California, a vocabulary of landscape that continues to endure. The vocabulary of landscape has consisted of exotic plants, arranged in the suburban context, around luxurious lawns. This extraordinary mix of plants, which reflects the discoveries of the colonial period, forms the backbone of landscaping today. It is over a century old.

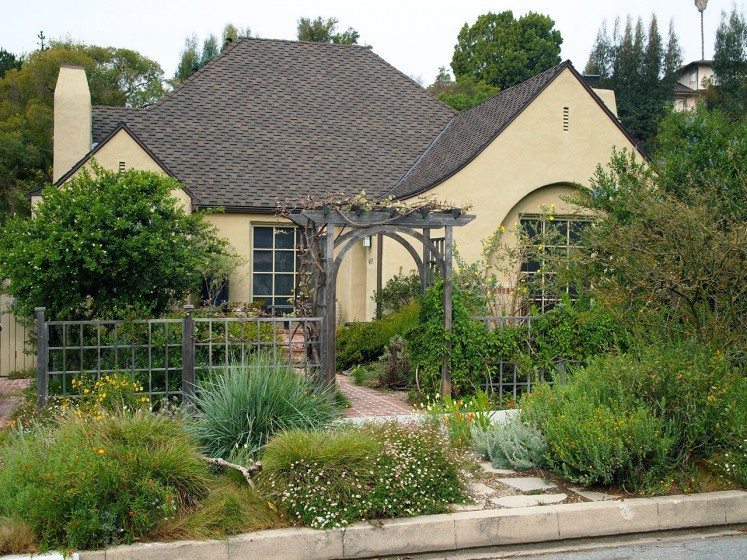

Where and how should this well-anchored landscape vocabulary evolve? Going to nurseries offers little evidence of widespread change or an alternative palate of plants, other than exotic succulents and a few cacti. Promotional displays of “water saving” and even “native” plants at most nurseries and garden centers are stocked with exotics from Australia and South Africa—clearly neither California native plants, nor necessarily ‘California friendly’ plants. Landscaping companies, such as Turf Terminators, have sprouted up, offering a bedding of rock (often white) underlain with landscape cloth and punctuated with a smattering of small, oddly assorted plants that are unlikely to grow into an attractive landscape, if they grow at all. Alternatively, people have chosen artificial turf, deep and intensely green, installed like wall to wall carpet (often with wrinkles) over bald earth, with a small border of landscape plants, again from somewhere other than California. Finally, there are the landscapes dominated by either decomposed granite or wood chips, sometimes colored an unnatural red. This opportunistic landscape reduces biodiversity in soils and the biodiversity of the insect, pollinator and bird communities. It is really Lawn in another form.

Overall, one can only hope that these are experiments on the way to a more evolved and place appropriate response to the need for less water intensive gardens. For this transition to take place, there is a critical need for appropriate plants, especially California native plants—plants that thrive on 30 percent to 80 percent less water than conventional gardens, require no fertilizers or soil amendments, rarely require pesticides, attract beneficial pollinators and pest-consuming insects, and create habitat for butterflies and birds, all while being stunningly beautiful and fostering a strong sense of Southern California as a distinctive place.

To get more native plants in the landscape, we need to expand horticultural knowledge and ensure the emergence of a corps of skilled horticulturists. We need more natives grown by wholesalers and sold by retail nurseries, and more skilled gardeners to care for them. Many people in Southern California no longer garden for themselves and simply hire the proverbial “mow and blow” team to take care of their gardens. Lawn care is their specialty, and blowing leaves and detritus is their task. Keeping the place tidy seems to be their goal, rather than creating something aesthetically pleasing, or plant nurturing. (In some ways, this lack of interest by residents in gardening on their own property is paradoxical given the renewed interest in urban farming.)

There are efforts around Los Angeles and around the state to provide professional development for front-line gardeners, but few are truly tailored for the general audience. Instead, these efforts seek to serve government workers and mid-sized to large landscape companies. Although most classes are offered in Spanish—the dominant language in the local landscape industry—as well as in English, many are held during gardeners’ regular work hours (which are most of the daylight hours, seven days a week). Larger landscape companies may provide professional development opportunities for their staff, but independent gardeners, who care for the majority of gardens, certainly don’t budget for the fees and time off required to be certified as native plant landscapers. Unless the range of professional development is expanded to serve “mow and blow” gardeners, it will only perpetuate earning and skills gaps in the landscape field, as well as a landscape vocabulary that is weak and thin.

Programs to encourage wholesale nurseries to grow more native plants simply do not exist and, like any successful business, the nursery business has evolved to grow plants efficiently. It knows how to grow the plants it distributes to the retailers, understands the time it takes to get them to market, and the fertilizer, pesticide and water regimes necessary to keep them looking their best. Native plant growing needs to be learned, and tried and true techniques may not be optimal. The necessary water regimes are different, potting soil requirements are different and propagation often can be quite different. But without the stock provided by large nurseries, the retail nurseries, now predominantly associated with big box stores such as Lowes or Home Depot don’t have native plants to sell. Dedicated gardeners can find California native plants, but the supply is limited due to the small number of specialty nurseries.

Even more surprising, perhaps, is the apparent lack of landscape designers who are versatile with California native plants and can design with them. Many of these designers—who could dramatically shift water use in affluent areas through new garden designs, since the affluent use up to three time more water than anyone else—don’t seem to have developed the skill to create native plant-filled trophy gardens. So, in a region obsessed with appearance, it is unfortunate that the rich and famous have not taken on transforming their mesic landscapes to showcase California natives as part of their public environmental ethic.

There is a whisper of precedent for a sustainable local landscape vocabulary. Early in the 20th century, concurrent with the establishment of major public gardens and estates in Los Angeles, there was a growing interest in native plants, spurred in part by accelerating development. Plants were collected across the state, as were seeds. Botanists and explorers sent their finds to natural history museums, including the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco and the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles, and a few pioneers started cultivating the plants. Theodore Payne was one such individual.

Payne started a Los Angeles nursery in 1903 that sold natives as well as exotic plants, and he had a hand in developing the first public native plant garden in California for the 1915 Exhibition, the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, the Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, and the original native plantings at Descanso Gardens. Payne influenced his cohorts, including Charles Fletcher Lummis, who built the Southwest Museum to house the largest collection of Native American baskets (and other artifacts) in the United States. There was, among this artistic, literary and philanthropic vanguard, interest in the native. Today, the Theodore Payne Foundation is continuing Mr. Payne’s work and is one of the most important sources of native plants in the region, as well as seed and horticultural expertise. But the Foundation is small, and the transition to a true, rich and appropriate Southern California landscape is urgent, requiring us to build on this heritage of valuing the biodiversity, building materials and artisanship native to Southern California.

Encouragingly, between people’s desire to live locally and save water, native plants are coming to wider attention, even for those who hire gardeners. People start with the idea that they can have a beautiful garden and save water at the same time. Then they learn that, while lots of perennials use less water than conventional lawns, native plants deliver many benefits that other plants just don’t have. Creating habitat and nurturing wildlife are a huge draw for many gardeners. The next step is often a reflection on place: its special aspects and history, and the possibilities raised by consciously choosing to live in this place. Imagine what it would be like if half the plants in Los Angeles were from Southern California. The smells alone would be amazing! Sagebrush and salvia would scent the air, creating the distinct impression of being in a particular place. There would be butterflies and flocks of birds because forage would exist: flowers, caterpillars, berries and bugs. A real dream of a real place.

But we do need the infrastructure to make this change come about. Although water utilities have initiated the change with cash for grass programs, so much remains to do. Even those folks who put in natives won’t have a successful garden without skilled gardening care. There is a reasonable fear that gardeners—who have so much influence over what most homeowners put in their yards—will restore all those lawns once water restrictions loosen, lawns they know how to care for, replete with the use of automatic sprinklers set to go off rain or shine, summer or winter, without utilizing any intelligence, without interest in calibrating for weather, soil moisture or plant type.

These concerns raise the question of how change occurs. The media has shown true delight in pointing the finger at the wealthy, who are water hogs, and their homes, with dozens of bathrooms and large lots that use 10,000 gallons of water a month. But attention to the structural obstacles—lack of plant stock, lack of horticultural knowledge about California native plants and a loss of domestic interest in gardening—has been mostly absent in press accounts and public policy. Without a comprehensive approach to landscape change in the region, change could take much longer, or the landscapes that get planted will continue to be haphazard, unattractive, biological dead zones.

Southern California is ripe for a new vocabulary of landscape, new garden design, new visions of what it is to live in this bioregion. Fortunately, there is a cohort of native plant aficionados, a growing appreciation for the water constraints of the region and an interest in gardening. A little help from the design community, a few incentives and training for wholesale nurseries to grow natives, and some prominent examples of the new style could go a long way to propel a transition. Good training for gardeners would have huge multiplier effects throughout the economy, and could be coupled with the deployment of much better irrigation technologies. The other important element in this change is patience—such a large-scale transformation will require time, and the assistance of tastemakers.

Stephanie Pincetl and Kitty Connolly

Los Angeles

about the writer

Kitty Connolly

Kitty Connolly is the Executive Director of the Theodore Payne Foundation for Wild Flowers and Native Plants. Her goal is to transform Los Angeles’s landscape to 50 percent native plants.

Leave a Reply