Out of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals, SDG 11 is a standalone goal for urban sustainability, with defined targets and indicators. SDG 11 can help urban policy and decision-makers and local people to think about and work towards urban sustainability. Most cities in developing countries, including in Africa, lack capacity for effective urban planning, a shortcoming which, in part, leads to a failure to protect urban biodiversity amidst the challenges of rapid urbanisation. The story of the royal bats of Kano city represents the key challenges of urban environmental sustainability in developing countries.

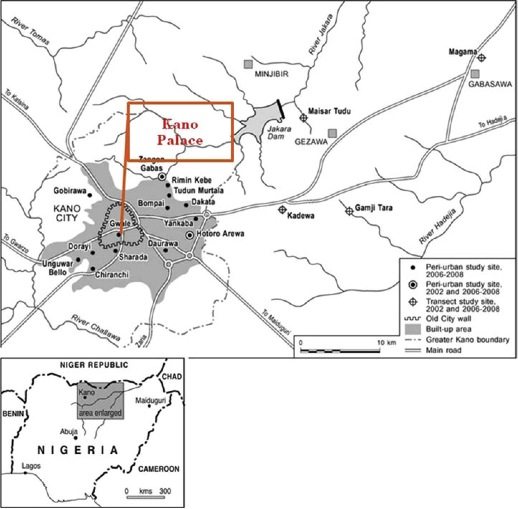

Here I’ll discuss the survival of bats in an intensively urbanised Kano city and its periphery. This discussion supports arguments made by Mark Hostetler in his recent post about the value of conserving forest fragments and individual trees in urban areas. In that article, he suggests that forest fragments and individual trees render some supportive services for migratory birds. In this context, looking at the role of Kano Emir’s palace will provide key insights into what fragments or remnants of green areas can do in supporting biodiversity in densely urbanised cities. Kano city and its surrounding urban areas, with an estimated population of about 3-4 million inhabitants, constitute the largest urban area in Northern Nigeria. The ancient city of Kano dates from the late 10th century, and the city’s walled perimeter covers an area of 29 km2.

The Kano palace, also called Gidan Rumfa, was built by King Muhammadu Rumfa between 1479 and 1482. Since that time, it has remained the largest traditional palace in Sub-Saharan Africa (Nast 1996), as well as the oldest and continuous seat of traditional authority in Nigeria. The Kano palace has attracted the interests of many researchers and visiting heads of state and governments, including the Queen of England, the U.S. President, the British Prime Minister, and HRH Charles, the Prince of Wales. Compared to an average home in Kano city, the Kano Palace covers an area of approximately 14 ha and is surrounded by walls of 6–9 m. high outside and, on average, 5 m high within the palace complex. The high walls of the palace surround the royal gardens (sheka, in Hausa language). The western garden has a length of 325 m and an average width of 85 m., while the eastern garden has an approximate length of 370 m and an average width of 45 m. The two gardens constitute about 45 percent of the total palace land area; the built area covers roughly 30 percent of the palace, while the open spaces represent about 25 percent of the total palace land area. The residents of Kano city have always considered the Kano palace as a city within a city by virtue of its size, spatial patterns, and organisation of space. In the context of urban sustainability indicators, including SDG Goal 11 and the Singapore Index, the proportion of green and open spaces makes this intra-city extremely favourable for sustainability.

Compared to the extremely dense and dry parts of Kano city, the Kano palace gardens provide a sanctuary for birds and some fauna, and possibly for migrating birds and insects as well. The palace also provides refugia to bats—chiroptera. A number of studies have investigated the effects of urbanisation on bats species, which ranges from loss of habitat and fragmentation to pollution. Most previous studies and this author’s experiences with Kano city have indicated a notable decline in urban biodiversity due to the progressive decline of green and open spaces. Less birds are observable on the ground and in the skies—not so for bats. In 2010, I conducted some studies inside the gardens of Kano palace, where I observed thousands of bats that flew and roved in the skies of the palace simply because of my perceived movements and the movements of the people following me. The gardens are about the only sanctuaries where the bats are left undisturbed; now they have become dominant species in the relatively undisturbed palace gardens and, in this way, they have become royal bats!

It is widely assumed that the palace gardens are as old as the palace itself (which was built in the 15th century). I want to believe that the bats offer some notable and yet unexamined ecosystem services in the palace and the city at large. Ecologists suggest that insect-eating bats help in controlling disease vectors, while fruit-eating bats help in fertilising soils with their guano and in dispersing seeds for flower pollination and forest regeneration. For the people around the palace and the people residing in the palace, the take-off time of the royal bats is a fascinating sight. And for the palace itself, the bats help maintain its security: any unusual movement in its gardens triggers movement of the bats, which alerts everyone in the palace. Bats really prefer places with minimal human movement and disturbances. This is understandable in the case of the royal bats; once, I saw helicopters hovering over the garden when the Nigerian President was visiting the palace. The noise of the hovering helicopters caused the bats to fly in the early afternoon hours.

While the Kano Palace has provided safe living spaces to thousands of birds for such a long time, it is thrilling to see the bats when they depart the palace in the late afternoon or early evening to search for foraging spaces mostly outside the old city, where different species of fruit bearing trees and ponds can be found. It is interesting to observe the bats while they fly out in chorus from the palace almost at the same time but in different directions—directions most probably dictated by needs for food, water, or something else.

Although, the old city is massively urbanised, two to three kilometres north of the palace is the greener and planned section of urban Kano. This area once housed colonial and corporate residential areas and has been able to maintain some old trees, including local and exotic species. Hence, it is easy to see some of the bats making an early descent in this area, probably to access fruit bearing trees. South of the palace and outside the city walls, there are remnants of ponds around the disappearing city walls and clusters of trees located within the perimeters of the Kano zoological and botanical gardens, as well as clusters of trees found in the industrial areas. The western and northern parts of the palace are the oldest and most densely peopled parts of the city. However, as the bats move farther west, they find institutional buildings: schools and university campuses that keep some trees. It is obvious that some bats fly at higher altitudes and may be moving to far away distances into farmed parklands in the urban periphery.

Bats are nocturnal mammals; this life history trait works well for them as it reduces competition with birds at water and feeding spots. Indeed, the royal bats of Kano city owe their continued existence in this intensively urbanised city to the continuous existence of the Kano palace gardens. The bats may not survive in other fragments of green spaces in the city because they are too exposed to humans and other species.

The story of the royal bats of Kano city represents the key challenges of urban environmental sustainability in developing countries. In many African countries, urban planning professionals and agencies have lost track of what to do or how to go about the business of greening congested cities. However, based on the example of the situation in Kano, it is obvious that small pockets of green areas can play a tremendous role in securing biodiversity. Importantly, indigenous institutions play an even greater role in this context. Indeed, the ability of the Kano palace to maintain its greenery for centuries is of great interest to contemporary urban sustainability.

It does not take specific budgetary allocations to maintain the royal bats, since that comes as part of the costs of maintaining the palace gardens. Although the gardens are exclusively for the use of the Emir of Kano and his closest family members, the preservation of the gardens through generations and dynasties is amazing. I am of the opinion that public conservation organisations should consider the use of the concept of payments for ecosystem services, which, in this case, should entail making some funds available to the palace as a compensation for keeping the gardens so that they are maintained as a base or sanctuary for biodiversity conservation in a rapidly and intensively urbanising city. Indeed, there is need for more studies to explore the nature of ecosystem services of the palace gardens and ecosystem services derivable from the royal bats, as well as potential conflicts between the bats and humans in their foraging spaces.

Aliyu Barau

Kano

References

Barau, A.S. (2015) Barau, A.S., Macnochie, R., Ludin, A.N.M.; Abdulhamid, A. (2015). Urban morphology dynamics and environmental change in Kano, Nigeria. Land Use Policy 42, 307–317.

Barau, A.S., Ludin, A.N.M., Said, I. (2013). Socio-ecological systems and biodiversity conservation in African city: insights from Kano Emir’s Palace gardens. Urban Ecosystems 16 (4), 783–800.

Barau, A.S. (2007) The Great Attractions of Kano. Research and Documentation Directorate, Government House Kano.

Ghanem, S.J., Voigt, C.C.(2012) Chapter 7 – Increasing Awareness of Ecosystem Services Provided by Bats, In: H. Jane Brockmann, Timothy J. Roper, Marc Naguib, John C. Mitani and Leigh W. Simmons, Editor(s), Advances in the Study of Behavior, Academic Press, 2012, Volume 44, Pages 279-302,

Russo, D., Ancillotto, D. (2015) Sensitivity of bats to urbanization: a review, Mammalian Biology – Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde, 80, 3, 205-212,

Simon, D. et al. (2015) Developing and testing the Urban Sustainable Development Goal’s targets and indicators – a five-city study. Environment and Urbanization, DOI: 10.1177/0956247815619865.

Leave a Reply